A look back at Neil Young's doomed hi-res audio player on its 10th anniversary

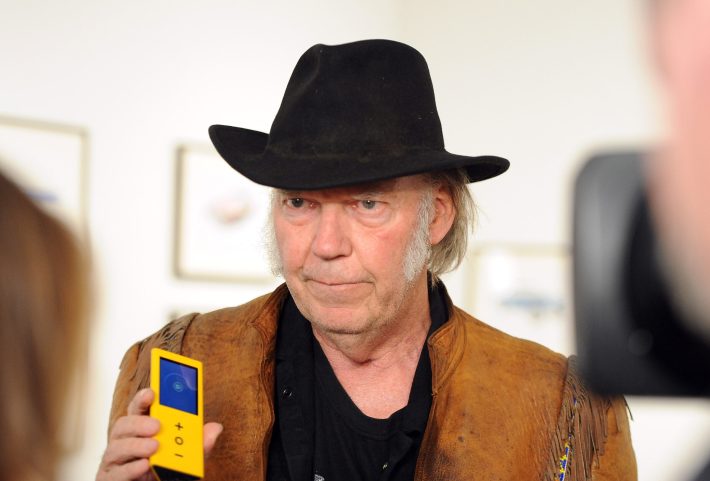

In the 2019 book To Feel The Music: A Songwriter's Mission To Save High-Quality Audio, Neil Young describes an encounter he had with Elon Musk. This encounter took place around the time Pono, Young's hi-fi digital music player and online store, was released 10 years ago this month, as Young was aggressively proselytizing about the importance of sound quality to anyone who would listen.

Young had been going to various carmakers in an effort to demonstrate Pono's capabilities and had gotten in touch with Musk about the idea of hooking up a PonoPlayer to one of Musk's Tesla vehicles. Young wanted Musk to compare the results to Tesla's stock sound system, but immediately they hit a snag: The set-up would require a wire to connect to the Pono. "Oh, we can't have a wire," Young remembers Musk saying. Despite this being a conversation only about the necessities of a demo, the notion of the visible wire in a Tesla marked the end of Musk's interest in Pono.

"Elon just didn't get it," Young says in the book, which was co-written by his primary Pono compatriot Phil Baker. "Music. Not everyone hears it. But given a chance, they would feel it."

At the time, Musk was far from alone in having little patience for Young's beliefs. After all, the Godfather of Grunge has long since earned a reputation for also being the Godfather of Gripe; just ask Stephen Stills or David Geffen — or, more recently, Daniel Ek or the very stressed-out operators of the Glastonbury Festival. Young's latest soapbox issue in 2015 was his insistence that the quality of digital music was in a tailspin. Because of this, he had created not just the PonoPlayer, which was capable of processing complex music files at a lower price than essentially any other mobile device available, but also PonoMusic World, an online audio store dedicated to offering the highest quality digital downloads.

"I didn't listen to music for the last 15 years because I hated the way it sounded," Young said in a launch Q&A at Las Vegas' Consumer Electronics Show in January 2015. "It made me pissed off and I couldn't enjoy it anymore. I could only hear what was missing." Prices for PonoMusic albums were more expensive than their iTunes versions (Taylor Swift’s 1989 cost $19.79 while the Who's Super Deluxe Quadrophenia was $43.29), though the Pono player could play your MP3s too.

Young's was not the first hi-def audio store; HDtracks, for example, launched in 2008. But there was initial enthusiasm around his new product. He first unveiled the device on The Late Show With David Letterman in the fall of 2012 and when crowdfunding was rolled out a year and half later it amassed $6.2 million in pledges and preorders — enough to constitute the third-most successful Kickstarter campaign ever at that time. But after the product was released, opinion began to sour. "A tall, refreshing drink of snake oil," was the headline of Ars Technica's review. "Out Of The Blue And Into The Wack," said Slate. "It Sure Seems Like Neil Young's Pono Player Is Bullshit," this publication wrote. (That headline made it into Young and Baker’s book, by the way.) The name Pono comes from the Hawaiian word for "righteous," but the device — a $399, bright yellow, Toblerone-shaped middle-finger to the iPod — was seen by many as simply self-righteous.

Looking back on the doomed Pono saga — in some sense the full-force project lasted just over a year before the online store was shut down — Young's Musk anecdote stood out to me. To Feel The Music was written before Musk drastically increased his bizarre behavior, but here was Young putting ink to paper of his own poor opinion of the technocrat several years before everyone else. Many have recently reassessed their initial opinions of Musk, wondering just why, exactly, they had thought so highly of him in the first place. Perhaps the opposite reconsideration was due to Pono itself.

Let's just get this out of the way: I have never even heard a Pono before. And yet for some reason I've spent the last 10 years harboring judgment solely based on its reception — the way it garnered a general eye-roll from many in the music community. But few true film lovers really scoff at the notion of something like the superiority of watching a movie on film, for example. Why was this any different? Why was it so controversial to suggest that an iPod wasn't the best way to listen to digital music?

"I've been working for hi-fi magazines for nearly 50 years, and it's always been like this," said John Atkinson, the recently retired longtime editor of prominent audiophile publication Stereophile. "There's a general sort of scorn poured on people who like to listen to music with better fidelity. … I think Pono just happened to be a victim of that."

Stereogum is an independent music publication supported by readers. Become a VIP Member and get exclusive articles, Discord access, ad-free browsing, and more.

With the dust long since settled on Pono's corpse, I thought those involved in the project might be open to sharing their thoughts on it all: If Pono wasn't given a fair shake, surely they'd want to talk about it. But when I reached out to many former employees for an interview, the response was almost entirely silence or no comment, including for Young, whose representative said he was unavailable.

Pono's CEO at the time of the launch, John Hamm (not to be confused with Jon Hamm), initially agreed to an interview but then didn't pick up the phone at our agreed-upon time. Hamm later emailed with newfound concern over my story: "I'm really the ONLY person who understands the last few chapters of the [Pono] project," he wrote, "and there's NO upside for me in having that all out in the press… I'm still friends with Neil and I don't think he'd appreciate anything I might say that was then taken out of context, for no really good reason…"

But Phil Baker — who was instrumental in Pono from day one, eventually serving as its COO — was more than happy to talk. He said he attempted to be honest about the entire Pono story, warts and all, in writing To Feel The Music with Young, and that he didn't know what Hamm was talking about. (Hamm never replied when I asked if he would elaborate.)

If Pono was something of a failure, Baker, anyway, has other successes to rest his laurels on: He did product development for Polaroid from 1967 to 1983 and Apple from 1994 to 1997. Today, he's the CEO of Neil Young Archives, an interactive, high-res streaming site exclusively featuring Young's vast catalog of music. Baker is well aware of the baggage that comes with representing Pono at this point, but he still stands behind the product and the general argument behind it: Improving the quality of recorded music needs to be an active focus for companies distributing it.

"I designed [Polaroid] cameras," Baker said, "and we were always trying to make sharper and sharper lenses and better and better film. Nobody ever said, ‘Gee, it's sharp enough. Let's not strive to make it better.'"

The question of whether audio quality technically went down in the digital age isn't really up for debate. In order to fit thousands of songs onto an iPod in the 2000s or create music that could be streamed seamlessly on Spotify in the early 2010s, files had to be compressed. Information in those files would be lost — and that was the basis of Young's entire argument. While every other type of entertainment technology seems to be getting digitally bolstered — movie files larger and TVs crisper, for example — music is frequently being digitally stripped apart. (By comparison, a CD's bitrate is 1,411 kilobits per second versus Spotify's "normal" level of 96 kbps.) The real question, however, is if anyone can tell the difference — or if there's any way to prove the superiority of one music file versus the next.

Those judging the quality of their listening experience carry the baggage of taste, experience, and broader general biases — and there are no performance standards that dictate music released for mass consumption. Every song has its own production approach, and people listen on various audio formats and systems. It's a fractured landscape in which we all have our own instincts about what sounds best based on prejudices we couldn't even begin to account for. You're well within your right to be skeptical when a music legend steps into this complicated world and tries to sell you something "better."

But on some basic level, Pono's reputation as snake oil is easily rebutted by the simple fact that snake oil, by its very nature, is a scam designed to make money. Young spent painstaking years developing Pono, to the point that the meticulousness of it as a project was a liability, particularly as it was attempting to take on a behemoth company like Apple, which never slows down. Simply put, Pono wasn't a money-making scheme — it was a money pit.

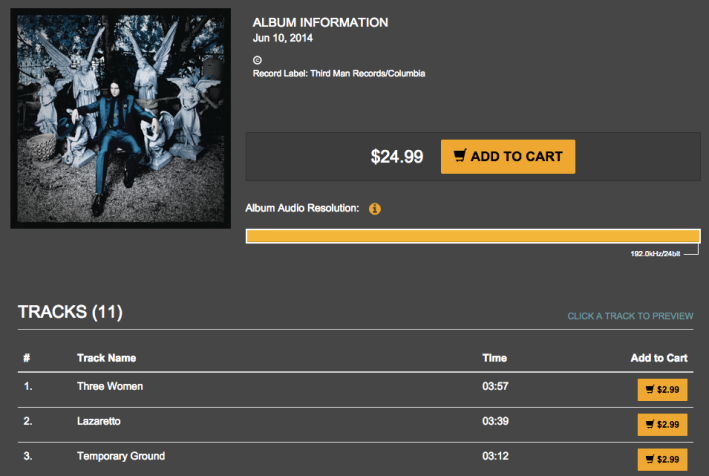

The main reason the PonoPlayer was shaped like a Toblerone is it needed more physical space than other music players to fit the battery and hardware, which was developed in collaboration with the late Charley Hansen, a highly respected audio engineer behind Ayre Acoustics. There was clearly a genuine attempt at making a product that worked better than its competition; it wasn't filled with air. And plenty of people tried it out and were impressed — especially when the camera was rolling. "We just heard the best-sounding digital music I've ever heard," Gillian Welch said in Pono's Kickstarter promotional video, in which a murderers' row of famous musicians (including Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty, Elton John, Patti Smith, Sting, Elvis Costello, Eddie Vedder, Jack White, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Foo Fighters, Arcade Fire, James Taylor, Beck, Emmylou Harris, Dave Matthews, and so many more) reacted to music played through a PonoPlayer in one of Neil Young's cars.

Still, when Pono was finally released, there were immediate questions about whether the device delivered audible benefits. The most substantial skepticism came from a Yahoo! review, by David Pogue, which still haunts the Pono world like the summer sun on a chocolate bar. As part of his review, Pogue had a group of individuals do a blind A/B sound test between a Pono with Pono-grade files and an iPhone with iTunes-grade files. Participants listened to a few songs on both — with headphones and earbuds — and then chose which version they preferred. A decisive majority chose the iPhone.

Pogue's takeaway: "If you want a better, richer, better balanced, less tiring, more comfortable listening experience, you don't have to spend $400 on a new player and throw away your existing music collection. Just spend a couple of hundred bucks on a nice pair of headphones."

Critics seized on these results, but not everyone felt they were a fair representation of Pono's capabilities. "Pogue's tests were not scientific," said Atkinson, whose own 2015 Stereophile review of Pono — complete with elaborate performance measurements — was glowing. (It was later awarded Stereophile’s Digital Component Of The Year award.) "He was not asking them to detect which one was better — he was actually doing a preference test. And people will always prefer the sound with which they're most familiar."

What Atkinson is suggesting is a form of audio Stockholm Syndrome. It's the notion that, after years of listening to lower-grade music on lower-grade platforms, most listeners have come to instinctually prefer it. His assertion of this phenomenon dug up an old memory of mine, when I was trying out the speakers on a new laptop I had just bought in 2020. After playing music on the brand new MacBook, and then comparing it to my old MacBook, I was convinced at first that there might be something legitimately wrong with the new speakers. It just sounded off to me — to the point that I asked my roommate to come over and see if he agreed. Eventually I realized the new speakers were certainly better, and that I had just grown attached to the particular sound of what I had been hearing for many years.

Still, Atkinson wasn't saying blind tests can't be used; just the opposite, actually. He emphasized his belief that many blind tests taken and facilitated over his career have indicated the clear superiority of high-resolution files: "Yes, sometimes the differences can be small," he said, "but they're always in the same direction — the high-res file will sound better than a CD-resolution file, and very much better than an MP3 file. So I don't know where these people are coming from." (Pogue could not be reached for comment.)

But Atkinson wasn't the only one who did a Pono review that included specific performance measurements — and some of those that did were far less complimentary. In 2023, a retrospective review was posted in Audio Science Review by the site's founder, Amir Majidimehr. He tested the PonoPlayer in the same fashion that he tests many pieces of audio equipment, and came up dissatisfied, saying it would rate "below average" compared to a standard CD player. (That is to say, higher than Spotify quality but lower than high-res digital, which can reach above 9,000 kbps.) "Clearly very little attention was paid to verifying the device actually performs at the level that was assumed," Majidimehr writes.

The added wrinkle to this review is that Majidimehr ultimately points to Atkinson's original measurements as demonstrating "just as awful" results. And yet Atkinson himself interprets his tests as illustrating a superior product; clearly they are not on the same page about how to grade certain audio performance measurements. Even in the scientific realm, it seems, people struggle to agree how to assess audio quality. Like music itself, these conversations partially exist in an indescribable, intangible dimension, unable to be fully grasped.

Majidimehr doesn't just have a poor opinion of Pono — he has a poor opinion of any claim that file quality is a major factor these days. "[Young] misjudged it," Majidimehr told me over the phone. "In this era, the difference is not audible."

The way Majidimehr explains it, a listener can pick out the higher quality recording if the test is not blind — if you know when to be looking for more detail. "Your brain changes," he said, "and actually can tell your hearing system, ‘Pay attention now.' You're listening for the smallest detail, you're listening for the background, you're listening for individual notes. Now you hear things that the first time around your brain ignored, and that is associated with fidelity."

Majidimehr ran the digital media division at Microsoft during the time they developed the soon-to-be-doomed Zune player, and he said he opted out of the project because of how futile he felt it would be from the beginning. Apple — with its baffling level of resources and scale — was just insurmountable, even if you're Microsoft. Add the Apple monopoly factor in with the rise of streaming, and that's all she wrote for Pono.

"The streaming part of it sucks, the hardware part of it sucks," Majidimehr said. "Which means that I don't care if you did have a quality advantage — the whole [Pono] thing is going to fall apart, once you get tired of subsidizing it. So the end outcome was sort of predictable."

Phil Baker said they knew even as they were developing Pono that the rise of streaming was a problem — that they "were late for what we were trying to do." The end result, as Atkinson put it, was a device that was "the equivalent of the best iPod ever introduced at a time when iPods were already fading." Eventually, the final nail in Pono's triangular, yellow coffin was when their store's content partner, Omnifone, was purchased by Apple in 2016 and then promptly shut down, taking a crowbar to Young's already fragile business. Pono's demise may have simply been unintentional collateral damage by Apple, or maybe Apple didn't like Pono reminding people that sound quality is something they could demand as a music customer. Either way, it was Goliath delivering the final blow to defeat David.

Reflecting on it now, Baker doesn't see the Pono project to be a failure. He said the 25,000 units sold in their first year was more than the collective total of competitors at their level, and that there's still an active base of people who happily use their PonoPlayer. The way it's spun by Young and Baker in their book is that Pono helped move the conversation of digital audio quality forward, leading to hi-res streaming platforms like Tidal and Qobuz carving out markets for themselves. "It was responsible for the fact that today you can easily get high-res music at the cost of low-res," Baker told me. "It's no longer a luxury."

But I've started to wonder if the opposite is true — if the strained perception of Pono actually set the conversation back in the mid-2010s, allowing Spotify to get an authoritative hold on the global music ecosystem without any prioritization of sound quality. Given Spotify's track record of diminishing the value of music in exchange for boosting its omnipresence — of finding ways to increase your passive listening time at all costs — it seems noteworthy that they have consistently been among the worst major streaming platforms when it comes to audio quality. If there's something about higher fidelity that strikes Spotify as antithetical to what they're trying to accomplish, perhaps Neil Young had a significant point this entire time.

While I was talking to Baker, I mentioned that I had actually never had a chance to listen to a PonoPlayer, and he kindly said he'd send me one from his personal stash. "You should hear it," he said. But he later informed me that he couldn't find one that had a battery that wouldn't need to be replaced. I'll never know if Pono sounds like God, as Young said, but Baker did give me access to the Neil Young Archives, where I could try out the high-res streaming option (hovering around 6,000 kbps).

The NYA is designed like a floating timeline, which you can wheel this way and that to see Young's albums as they appear chronologically. Below the albums are historical tidbits to put the albums in context — Nixon resigns in the space between On The Beach and Tonight's The Night, Elvis dies between American Stars 'N Bars and Comes A Time. It's the kind of active-listening approach that would give Daniel Ek a fit. It also made my old computer start whirring.

I put over-ear, corded Bose headphones on and hit play on Rust Never Sleeps, where the factoid beneath it was the 1979 introduction of the Walkman. "Hey hey, my my, rock and roll can never die" — you know how it goes. Toggling between the NYA fidelity rates of hi-res, CD-level, and standard streaming, my brain did exactly what Majidimehr told me it would do: I noticed the difference.