In The Number Ones, I’m reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart’s beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

Something interesting happened in the ’80s: Progressive rockers became pop stars. All through the ’70s, many of rock’s more virtuosic musicians moved into triple-gatefold concept-LP space-out territory, pushing past psychedelia and into the heart of the sun. This music was often hugely popular; the biggest prog bands sold millions and toured stadiums. But an instrumental neo-classical zone-out that took up a whole LP side wasn’t exactly the kind of thing that often got radio play. In the ’70s, prog was its own corner of the music universe. For the most part, it didn’t intersect with pop.

In the ’80s, though, prog giants like Genesis and Yes changed course and started making bright, accessible, expensive-sounding yuppie pop. There were a lot of reasons for that, and we’ll get into them as this column gets into the decade. (Genesis and Yes will both appear in this column.) But at the dawn of the ’80s, the world got a sort of preview of what was about to happen. By the late ’70s, Pink Floyd, the British band who arguably popularized the entire idea of prog, were one of the biggest album-sellers on the face of the planet. Their 1973 LP The Dark Side Of The Moon, for instance, was a US #1, and it eventually spent 14 years on the Billboard album charts, breaking a record that had previously been set by a Johnny Mathis greatest-hits album. At this point, Dark Side is by far the longest-charting album in Billboard history; nothing else even comes close.

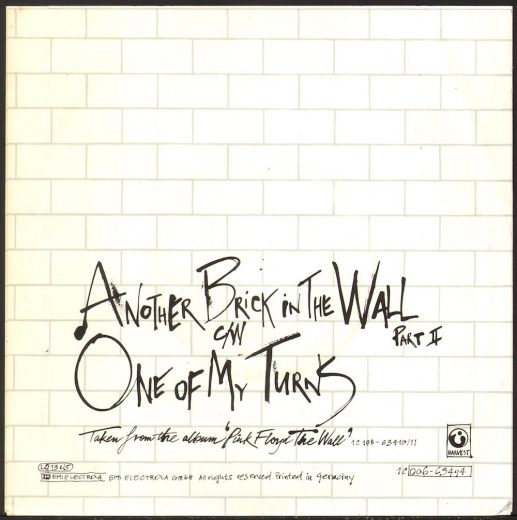

But Pink Floyd were never a singles band. This was very much by design. Floyd made grand and pretentious statement-albums, and they weren’t much into the idea of anyone isolating little pieces of those albums and selling them to the public. After 1968’s “Point Me At The Sky,” Pink Floyd went over a decade without releasing a single in the UK. In the US, they made it to #13 with 1973’s “Money,” but that was their only Hot 100 hit until “Another Brick In The Wall (Part II),” the song that gave them their first and only #1 on both sides of the Atlantic.

By the time they scored their one chart-topping single, Floyd had lived a whole life, and they were on the verge of breaking apart. Some version of the band had existed since 1963, when Roger Waters and Nick Mason met in London architecture school. The band started out under playing R&B covers at parties under the name Sigma 6. In the next few years, they added a few new members, including Syd Barrett, a charismatic art-student guitarist who’d been childhood friends with Waters. They went through a bunch of different band names. They found London club residencies and managers willing to spend a whole lot to buy them good instruments. They became Pink Floyd somewhere around 1967. In short order, they signed to EMI.

Pink Floyd were one of the first British bands playing San Francisco-style acid-rock, complete with light shows. Their dazed, drug-fried sensibility is all over 1967’s The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, their first album. All the drugs were too much for Syd Barrett, whose LSD consumption and depression were enough to make him completely shut down. The band reluctantly ousted Barrett in 1968, replacing him with guitarist David Gilmour, and then they wrote a whole lot of albums about how sad they were to be without him.

Pink Floyd had been huge in the UK from the jump; all their albums had gone top-10 over there. In the US, The Dark Side Of The Moon was the breakout. The two albums that the band released after that, 1975’s Wish You Were Here and 1977’s Animals, were both huge American successes. By the beginning of 1977, they were touring American stadiums, bringing their famously elaborate stage productions with them. They hated all of it.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a successful rock band more consistently miserable than Pink Floyd. The members of the band fought bitterly over credit and control. They blew through the money that they were making, to the point where they had to come up with something in 1979 because of bad contracts and tax issues. Roger Waters, who’d wrestled the dominant-songwriter position away from his bandmates, fantasized about shutting himself off from the audience, and his disdain came to a head at a 1977 show in Montreal, where Waters, pissed off about a group of front-row fans rocking out too hard, spat at one of them. This wasn’t fun punk spitting; it was fuck you, I hate you spitting. This was the impulse that led to The Wall.

The Wall, Pink Floyd’s absurdly ambitious 1979 double LP, was a concept-album rock opera about a depressed and angry rock star who’s been traumatized by various forces in his life — the death of his father, his smothering mother, his oppressive schooling, an infidelity-wracked marriage — and who eventually becomes a kind of fascist dictator. (The rock star’s name was Pink Floyd, which irritatingly means that all the clueless parents who called Pink Floyd a “him” and not a “them” were not technically incorrect.) Waters based the lead character on both himself and Syd Barrett. He wrote the whole thing alone before presenting it to the rest of the band, who went along with it even though they resented him.

In a canny move, Waters enlisted the help of the producer Bob Ezrin, who’d never worked with Floyd but who had plenty of experience making theatrical and high-concept rock music. Ezrin had worked extensively with the hugely successful Alice Cooper, helping Cooper and his band find their sound, and he’d also produced the 1976 KISS blockbuster Destroyer. Ezrin co-produced The Wall with Waters and Gilmour. He helped Waters turn The Wall into a half-coherent narrative, and he performed the difficult task of getting the mostly-estranged bandmates to work with each other. (This was not an entirely successful effort. The band fired keyboardist Richard Wright mid-production, though he stayed on as a session musician and even toured with them afterward.)

Where Roger Waters had envisioned “Another Brick In The Wall (Part II)” as a solo-acoustic number, Ezrin had the idea to put a beat to the song. He told Gilmour to go out to clubs and to check out the sound of disco music. Gilmour hated what he heard, but he helped the band come up with some version of it anyway. In its final form, “Another Brick In The Wall (Part II)” has a sort of clumsy sidelong strut to it. The beat isn’t strong, but it at least exists, which isn’t something that happened on too many Floyd songs. Nobody would mistake it for disco, but in its four-four pulse and in the quiet murmurs of Waters’ bass, you can at least hear some distant echo in there.

Of course, Pink Floyd were not interested in the sort of mass euphoria that disco promised. Instead, it’s a dour bummer of a song, a snarled protest against the harsh rigors of British schooling in the ’50s. There are three parts of “Another Brick In The Wall” on The Wall, and “Part II” immediately follows “The Happiest Days Of Our Lives,” Waters’ disgusted caricature of “certain teachers” who’d made his life hell more than 20 years earlier. (I always heard both songs played together as one on the radio.) Waters and Gilmour sang lead on the song together, and Waters played the voice of the evil Scottish schoolmaster, shrieking at the kids that they can’t have any pudding if they don’t eat their meat.

Waters had only written one verse for “Another Brick In The Wall (Part II),” and he bristled at Ezrin’s suggestion that the song could be a single. But Ezrin had a vision for the song. He’d worked with a kids’ choir on “School’s Out,” Alice Cooper’s immortal 1972 banger. (“School’s Out” peaked at #7. It’s a 9. “School’s Out” is one of Cooper’s two highest-charting singles; another Cooper single, 1989’s “Poison,” also peaked at #7. “Poison” is an 8.) Ezrin had a friend record a choir of kids at the nearby Islington Green School as they sang that first verse again, and then he edited it into an extended version of the song. Floyd loved the new version of the song, and they agreed that it could be a single.

The kids really do add something to the song. It’s one thing to hear a couple of rock stars in their mid-thirties singing that school is bullshit. It’s another to hear a whole horde of kids singing the same thing in exaggerated Cockney accents. Pink Floyd definitely earned plenty of goodwill by blowing millions of minds in the ’70s, and it was certainly a novelty to hear them going a tiny bit disco. But I think those kids are key to the success of “Another Brick In The Wall (Part II).” They’re just fun to imitate.

Every time a song hits #1 these days, people talk about how that song rose on the strength of a meme. But memes existed before the advent of the internet. They were just fun things that caught on with a whole lot of people at the same time. The kids on “Another Brick In The Wall (Part II)” were, I believe, the 1980 version of a meme. (The kids, incidentally, were not paid. This became a bit of a news story at the time. Pink Floyd sent albums, singles, and concert tickets to all the kids, and they made a £1,000 payment to the school. But the kids didn’t get royalties until decades later, when they successfully pushed for them after various changes in British copyright law.)

It’s probably instructive to compare “Another Brick In The Wall (Part II)” to Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out,” that previous Bob Ezrin production. Both songs have the same essential message: School sucks. (This message is entirely correct. Fuck school, and fuck all the certain teachers who, over the decades, have taken advantage of whatever power they had.) Both songs had instant constituencies in every kid who hated school, which is to say every kid. But Alice Cooper had fun with that message. He growled, he sneered, he joked, and he had a gargantuan hammerhead riff behind him.

Floyd, on the other hand, take themselves way more seriously. In its own way, “Another Brick” is funny, though I’m not sure that’s intentional. (Pudding? What the fuck?) The song is tough and impassioned, and it builds to a couple of cool moments — the hey teacher! on the chorus, the arrival of the kids’ choir. It has a simple but hugely memorable central melody. It has one of those guitar solos where every note sticks in your head, which makes it ideal for air-guitar purposes. And the song pulls off the rare concept-album trick of serving the overarching narrative while still working as its own discrete piece of music.

But “Another Brick In The Wall” is just not a great rock song. Musically, it’s watery and inert. Pink Floyd build up tension, but they never release it. David Gilmour’s solo is impressive in its own way, but it adds no fire to the song; it’s too crisp and noodley. Waters and Gilmour sing the song with a dark detachment that’s utterly lacking in charisma; the kids’ choir really bails them out. It’s dour and heavy and at least a little bit boring. Everytime “Another Brick In The Wall” shows up in some new trailer for some new high-school horror movie — as in the New Mutants adaptation that’s been delayed so many times that I can’t believe it’ll ever come out — I roll my eyes so hard I look like the Undertaker.

But “Another Brick In The Wall (Part II)” did its job. It sold the hell out of The Wall. The Wall went on to become, per Billboard, the highest-selling album of 1980 in the US. It moved more units than the Eagles’ The Long Run or Michael Jackson’s Off The Wall or Billy Joel’s Glass Houses. To date, The Wall has sold something like 30 million copies globally; it’s one of the biggest-selling albums of all time.

The Wall also launched a truly freaky 1982 movie adaptation from Bugsy Malone/Midnight Express director Alan Parker. Boomtown Rats frontman Bob Geldof played Pink Floyd (the man, not the band), and the film introduced the nightmarish vision of cartoon teachers running kids through meat grinders. The Wall did middling box-office business — it was up against stuff like E.T. — but it went on to become the kind of film that 12-year-olds show each other at sleepovers to freak each other out.

Pink Floyd didn’t last long after The Wall. The band toured arenas, playing the album in full every night, but they lost money on the enterprise because of the expensive production, which involved giant balloon versions of different characters from the album’s narrative. They barely spoke to each other on the road. Floyd never released another top-40 single, and Roger Waters left the band after one more album, 1983’s The Final Cut. Then he got into a bunch of court battles with his ex-bandmates over the rights to the name. Different configurations of Pink Floyd sporadically continued to release music, though; 2014’s mostly-instrumental The Endless River is supposedly going to be their last album. Waters still takes The Wall on tour whenever he feels like it, and he reunited with his old Pink Floyd bandmates for one show at London’s Live 8 in 2005. He’s richer than anyone you will ever meet in your entire life.

“Another Brick In The Wall (Part II)” does not sound much like the proggiest prog that Pink Floyd ever made. It doesn’t sound much like the high-impact pop music that Pink Floyd’s prog peers would make in the years ahead, either. It’s a halfway point, a waystation on the road to the land of confusion. We’ll get there soon enough.

GRADE: 6/10

BONUS BEATS: Here’s Korn’s cover of all three parts of “Another Brick In The Wall,” from their optimistically titled 2004 collection Greatest Hits, Vol. 1:

(Korn have never had a top-10 hit. Their highest-charting single, 2003’s “Did My Time,” peaked at #38.)

THE NUMBER TWOS: The Spinners’ joyous Motown/disco hybrid beast “Working My Way Back To You / Forgive Me, Girl” peaked at #2 behind “Another Brick In The Wall (Part II).” It’s an 8.