Last summer, when Blur were reuniting to record a couple new tracks and play the closing ceremonies of the 2013 Olympics, I wrote here about the great English band's 10 best songs. I opened that post by trying to answer in earnest a semi-rhetorical question posed on Twitter by Spin's Chris Weingarten. Asked Weingarten:

Serious question of the day for Americans: When exactly did Blur turn from enjoyable/ignorable singles band into OMG IMPORTANT ARTISTES

— Chris Weingarten (@1000TimesYes) August 1, 2012

In my response, I reasoned there were probably a few instances to which this transformation could most logically be traced, but if you wanted to point out when exactly it occurred, you'd have to look back to May 10, 1993. As I wrote to Weingarten.

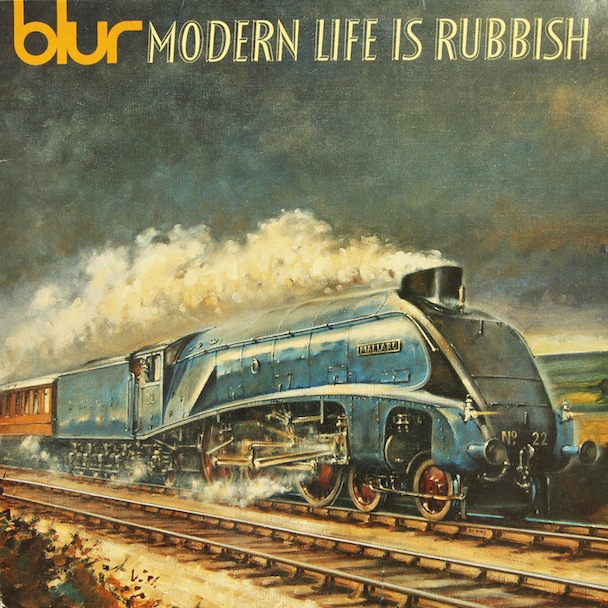

[R]eally, the point at which Blur made that leap came when they released their second album, 1993?s Modern Life Is Rubbish ... Here, [Damon] Albarn’s voice as a writer emerged -- both lyrically and melodically -- and [Graham] Coxon’s violent, acrobatic guitar abilities were first unleashed. (This is not to give short shrift to the contributions of bassist Alex James or drummer Dave Rowntree, who really do combine to create the most dynamic [and quotable] rhythm section of the era.) Modern Life became the first chapter of the band’s unofficial Britpop trilogy -- followed by ’94?s Parklife and ’95?s The Great Escape — which obviously came to define Blur’s identity for quite some time.

Today, May 10, 2013, Modern Life turns 20 years old -- and with the record,Britpop itself -- providing for us an apt moment to celebrate the album and its legacy.

It's an album born of bitterness, hubris, rage, resentment, and envy. It almost didn't happen at all, or it almost happened very differently. Both before and especially after the release of Leisure, Blur were not a band to be taken very seriously. Their 1991 debut, Leisure, was a mild, mostly generic collection heavily styled by Blur's UK label, Food Records, to echo the indie-dance music popular in Britain at the time: the Stone Roses, the Happy Mondays, the Charlatans, EMF, etc. It was a strategy that worked to a point: It yielded a top 10 hit ("There's No Other Way," which peaked at No. 8 on the UK Singles Chart) and two other singles that charted but failed to crack the top 30 ("She's So High" and "Bang"). But beyond that point came a series of diminishing returns that reached a painful nadir when Blur were sent to America to do 44 shows in a little more than two months.

In the States, Blur were at best a modern-rock novelty ("There's No Other Way" peaked at No. 82 on the Billboard Hot 100) and they arrived here at the peak of grunge; meanwhile at home, newcomers Suede had all but slaughtered the indie-dance cash cow and were crowned the new young royals of British rock. Consider this timeline: Blur's North American tour kept them on the road from April 14 to June 3, 1992. On April 25, just 11 days into that tour, Suede were on the cover of Melody Maker, hailed as The Best New Band In Britain; on June 30, mere weeks after Blur's tour had concluded, the Singles soundtrack was released -- three months in advance of the film -- because demand for grunge had reached an insatiable climax. Even if they had been moderately successful, it would have been hard for Blur to keep high spirits in such a milieu. But they were an ocean away from "moderate success." As the Blur Live Audio Archive Project says of the band's US jaunt: "Touring with the Senseless Things with no new album to promote, the penniless Blur were basically forced into this tour to sell T-shirts and merchandise to pay off debts their first manager, Michael Collins, had racked up with his colossal mismanagement and financial shenanigans."

In a 2000 Mojo feature, Dave Callaghan wrote of Blur's 1992 trek:

Drinking themselves insensible, [Blur] duly came to blows and pined piteously for England. For some reason -- homesickness, perhaps, or because he fancied filling in a few gaps in his knowledge of '60s music -- Damon listened to a Kinks tape throughout the tour.

That tour and its ancillary distractions would almost singlehandedly come to inform and inspire Modern Life: the escalating resentment of American culture; the Kinks tape; the competitive fires stoked by Suede. Albarn's bitterness toward his countrymen went beyond music: Yes, Suede were "the most-written about band in Britain," and yes, their self-titled 1993 debut album would enter the UK charts at No. 1 and be awarded gold status on its second day of release. Perhaps more notably, though, many of the songs on Suede were actually about Albarn's then-girlfriend, Justine Frischmann, who had been a founding member of Suede as well as the lover of that band's frontman, Brett Anderson, prior to hooking up with Albarn (and during that time, too: For a while, admits Frischmann, she was seeing Albarn while still living with Anderson).

"I just felt America had screwed me badly," Albarn told Mojo. "It had taken away a lot of my dreams ... Suede and America fueled my desire to prove to everyone that Blur were worth it."

So after spending a couple miserable months in a tour bus crossing America, listening to nothing but the Kinks, Albarn returned to London to create what Frischmann called "some sort of manifesto for the return of Britishness" -- an antidote and alternative to grunge, a condemnation of America -- and a record that would, per Albarn, serve as "Public vengeance and personal vengeance [and] dethrone Brett [Anderson] and his group of cretins."

It was a full-scale reboot with an intense focus on English culture: The band members lost their Leisure-wear look -- floppy haircuts and baggy T-shirts -- and outfitted themselves in sharp suits and gear from Fred Perry, Doc Marten, Merc, and Lonsdale: brands closely associated with England's skinhead and mod scenes. In one famous photo shoot from the period, they posed in front of graffiti that read, "British Image 1." Albarn was writing songs steeped in British pop, punk, pub rock, and mod traditions, cribbing bits of the Small Faces, the Jam, and -- most overtly -- the Kinks. In an interview segment on the BBC documentary series Seven Ages Of Rock, Albarn said, "[Modern Life] was me attempting to write in a classic English vein using kind of imagery and words which were much more modern. So it was a weird combination of quiet nostalgic-sounding melodies and chord progressions, [with] these weird caustic lyrics about England as it was at that moment, and the way it was getting this mass Americanised refit."

Albarn battled with Food Records boss Dave Balfe over the band's new direction: Albarn was convinced Blur would usher in a new wave of British popular music and British pride; Balfe was reluctant to bet his label's stakes on that conviction. Albarn eventually won. Blur went into the studio with a legend of English pop, Andy Partridge of XTC. Those sessions, though, were fraught with tension, and after a short while, Blur and Partridge abandoned the collaboration. The band eventually went back to Stephen Street, who had produced about half of Leisure, as well as the Smiths' Strangeways, Here We Come and Morrissey's Viva Hate. With Street, Blur recorded a robust collection of swirling melodies, sinewy bass, forceful beats, and jagged guitars, all accented by strings, woodwinds, and horns. The band submitted the masters to Balfe and Food in December 1992. However, the album was rejected by the label; Food demanded the band go back into the studio to record a viable single. This time, Albarn acquiesced, writing a new song called "For Tomorrow." Then, Blur's American label, SBK, balked -- the band was forced into the studio again, to record another new song, "Chemical World." SBK also requested that Blur re-record the album entirely -- this time with Chicago's Butch Vig, the producer behind Nirvana's Nevermind. Blur refused.

This is probably a good place to point out that the birthday we're celebrating today is that of the British release of Modern Life Is Rubbish. In America -- fittingly, perhaps -- the album didn't see release till seven months later, allegedly due to turnover at SBK. When the domestic version finally did come out, the sequencing had been altered, non-album single "Popscene" was wedged in-between what had been the album's two closing tracks, the demo version of "Chemical World" was swapped in for the Street-produced version, and a couple hidden songs -- British B-sides -- were thrown onto the CD as tracks 68 and 69. Throughout the recording process, the working title of Blur's second album was Britain Vs. America. The final title, though, came from a bit of graffiti Albarn saw spray-painted on a wall in London: Modern Life Is Rubbish. Albarn called the title "the most significant comment on popular culture since 'Anarchy In The UK.'"

Intentions aside, Modern Life failed to set England ablaze on impact. It produced three singles -- "For Tomorrow," "Chemical World," and "Sunday Sunday" -- all of which reached the top 30 but climbed no further. The album initially sold about 40,000 copies. In the States, it was a total non-starter; to those unfamiliar with the band, Blur were virtually indistinguishable from a host of other monosyllabically monikered Brit acts: Verve, Curve, Lush, Pulp, Ride, Suede, Cud ...

Context offers more insight than initial metrics, however; history has been much kinder to Blur than 1993 ever was. Modern Life is not a middling or faceless work -- it is a courageous and enormous artistic leap, and a cultural landmark. Their spaced-out poseur-baggy-isms shed like baby fat, Blur Mk. 2 deliver alert, energetic pop with violently slashing guitars, fluid rhythms, complicated arrangements, mousse-rich melodies, and harshly critical narrative lyrics. All of the singles are magnificent -- which is surprising (or not?) as two of those songs were label-mandated and created on demand. Album opener "For Tomorrow" is especially great (and I mean great); it's one of a handful of genuinely transcendent Blur tracks, a staple of their live set for 20 years now. And many of the non-singles are comparably wonderful: the snaking, explosive "Colin Zeal"; the perfect-pop jewel "Star Shaped" (whose title was later borrowed for a 1993 documentary on the band); the shimmering, hugely climactic "Oily Water"; the delicate, low-key, and lovely album closer, "Resigned." I'd argue, too, that the very best song of Blur's career is among Modern Life's deeper cuts: the timeless, miraculous "Blue Jeans." (In fact, I have made that argument!)

Even today -- with their anti-American period far behind them -- Blur seem to treat Modern Life as an album for England and England alone. Consider these statistics: At each of their two recent Coachella dates, Blur played sets of 15 songs (which were culled entirely from their seven studio albums); of those 15 songs, only one came from Modern Life ("For Tomorrow"). At their Hyde Park date last summer, on the other hand, Blur played 26 songs, seven of which came from Modern Life. And if you think about it, that makes sense: Beyond the jealousy and rage, Modern Life was an album that demanded England take pride in being English. In a 1993 interview with NME, Albarn said of Modern Life: "If punk was about getting rid of hippies, then I’m getting rid of grunge. It’s the same sort of feeling: people should smarten up, be a bit more energetic. They’re walking around like hippies again -- they’re stooped, they’ve got greasy hair, there’s no difference.”

Early the next year, in February 1994, NME held its inaugural Brat Awards Ceremony, celebrating the best in new British pop music. That year, Suede were named Best Band, while Frischmann's Elastica took home the award for Best New Band. Blur and Modern Life went home empty-handed. At the ceremony, a pack of journalists hounded Albarn about his "responsibility to save British music." Albarn was sanguine: "We've done it," he said. "We really have."

Less than three months later, Blur would release Parklife, one of the best albums of the past half-century and the first truly "classic" Britpop album. But the template was set by Modern Life -- not just the template for Parklife, but for Britpop itself, and for the British (and Anglophilic) culture that came to flourish around Britpop. Soon after that came Oasis and Trainspotting and Cool Britannia and a million pale, skinny bands wearing Fred Perry and playing guitars. Blur's battles -- public and personal -- had only just begun; Modern Life would come to represent merely the first of their many transformations. But that first transformation was the biggest by far -- as Blur bassist Alex James has said, it's the album on which Blur “went from being an indie band to a group with wider aspirations and yearnings.” He's too humble to note, perhaps, that it's also the one that kickstarted a movement. And 20 years later, it still sounds challenging and charged, incendiary and inspired.