Few bands can claim to have invented an entire genre of music. The Beatles didn't do it. The Beach Boys and visionary writer and producer Brian Wilson didn't do it. Frank Zappa didn't do it. Black Sabbath, a band once filleted by rock critics like Lester Bangs and targeted by generations of parents for allegedly ruining their children's lives, did. In the course of their long career (44 years and counting), Black Sabbath altered the sound of music, became a cornerstone for every teenager who didn't fit in and, in the process, redefined what was possible in rock.

Sabbath wrested rock away from saccharine producers, naïve hippies, and idealists, and gave it back to the folks that inspired blues music: the lonely, the desperate, the fucked-up, and the hopeless. Whereas blues offered a respite and a vacation from the dark night of the soul, Sabbath offered a trip to its heart. Their music allows you to confront your primal fears and, in the course of listening, transcend them. It also made -- and makes -- you feel completely alive. That's the riddle of Sabbath; a song like "War Pigs" can unite a stadium and create a makeshift family.

For most of the fans who loved Sabbath the T-shirt that read "Black Sabbath Ruined My Life" was the ultimate inside joke. If Sabbath did anything, it was save our lives. Let's go on a ledge: Black Sabbath might be the most influential band of our lifetime, the band that introduced what we think of as heaviness and wrote albums that will never be matched, much less copied. Black Sabbath changed the world, opening the minds of our embryonic cells to the never-ending well that is inspiration, the spirit, and the soul. Their music sparked one of the few revolutions that worked, a revolution of like-minded kids with guitars and dreams who didn't want to fit in or work the system; they wanted to find their way out. Those kids founded bands like Iron Maiden, Slayer, Venom, and Celtic Frost. In the world of metal, Sabbath is magnetic north; all compasses point to it, the alpha and omega.

The visionaries that started Black Sabbath -- guitarist Tony Iommi, bassist Geezer Butler, vocalist Ozzy Osbourne, and drummer Bill Ward -- rose beyond their humble beginnings in post-WWII England to become a global phenomenon, the fathers of heavy metal. To see how influential Sabbath is you only need to look at recent history; the band that once played dives in Germany and England decades later held a global press conference -- the kind of event typically reserved for Hollywood elites -- based on the news that they'd be writing a new record. Or, just go to your local record store -- if there's one left in your town -- and spend time in the heavy metal section. That section of the store is there because of Black Sabbath. You might as well call it the Sabbath section.

Despite their ubiquity and the press around brand-new comeback album 13 -- which just debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200, their first time ever topping the charts -- the roots of Black Sabbath aren't the roots associated with success, with boundless creativity, even with systemic change. Their work ethic and sound was forged in industrial wastelands and hopeless, dead-end neighborhoods. The young Sabs played in scarred husks of buildings left after Germans bombed England during World War II. Their parents were of the generation that fought in that world-defining conflict; as children, the Sabs grew up around the emotions and problems that would fuel their best music: hopelessness, despair, addiction, and the unflinching hand of Fate. The apparition in their eponymous song -- the figure in black, pointing -- could have been a foreman consigning them to a life of hard labor only broken up by a few hours at the pub at shift's end.

Early in their lives, the members of Sabbath appeared headed in a similar dead-end direction: Iommi worked in a sheet metal factory and thought his musical career was doomed when he lost the tips of two fingers, the most famous injury in rock history. He later learned to play around the injury -- and altered his sound -- thanks to the creative use of glue (with an assist from the Django Reinhardt catalog). Ozzy -- who advertised his vocal services in an ad that said "Ozzy Zig Needs Gig" -- worked in a slaughterhouse and a car horn factory. Butler and Ward came from similar humble circumstances.

The earliest versions of Sabbath were almost derailed when Iommi got an opportunity to play with Jethro Tull. He was poised for success -- and even appeared in the Rolling Stones' Rock N' Roll Circus -- but quickly decided that his future lay elsewhere. We're all musically richer for Iommi's decision to go his own direction, as he recounts in his biography Iron Man:

After I came back from London I said to the rest of the band: if we're going to do this, we're going to do it seriously and really work at it, starting with rehearsals at nine o'clock in the morning. Sharp! We booked a place in the Newtown Community Centre in Aston, across the road from a cinema, and started a whole new regime.

Sabbath's long career has yielded an array of musical riches: the blues drenched debut; the career-defining classic Paranoid; the progressive leanings of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath; the vocal heroics of the Dio era, and the eccentricities of Deep Purple vocalist Ian Gillan's brief dalliance with the kings of metal. Like you would expect from any band with four-plus decades of history, Sabbath's catalog is enormous and full of changes and detours, successes and also albums unworthy of the name Black Sabbath.

AC/DC -- another product of the '70s -- kept their sound and approach intact when original vocalist Bon Scott died and was replaced with Brian Johnson. Sabbath changed with the vocalists and times. The one constant through every incarnation has been riff master Iommi, who loaned his wares both to classic albums and records that, while intriguing, could never compete with the classic lineup or the Dio albums.

In today's hyperspeed musical world, four decades is the equivalent of a glacial shift. You could look at the pieces of Sabbath's career almost like archaeological history. There's the Ozzy era, which began when the band formed as the Polka Talk Blues Band and was called Earth before settling on the name on Black Sabbath, reportedly influenced by a Mario Bava horror matinee. The "classic" Sabbath lineup created their best-known albums, including Paranoid, Volume 4, and Master Of Reality, and lesser albums like Never Say Die! For some, this is the only lineup and the only Sabbath records that matter.

When Ozzy was fired for his addictions and teamed with Randy Rhoads to launch his solo career -- the pair collaborated on the essential Blizzard Of Ozz and Diary Of A Madman records -- the second wave of Sabbath began. The original lineup recruited vocalist Ronnie James Dio. Dio's diminutive frame housed a voice that became synonymous with metal vocals. That lineup recorded Heaven And Hell, one of Sabbath's greatest albums. The bloat of the late Ozzy albums disappeared and the edge returned. Dio's vocal range allowed Sabbath to go into different directions, whether it was pensive songs like "Children Of The Sea," rockers like "Country Girl," or later, "After All" -- a near-ballad given a proper outing during the Heaven And Hell tours that, sadly, were a farewell for Dio before he died of cancer in 2010.

The third wave is known as Purple Sabbath, which included the Born Again album and the tours with Deep Purple vocalist Ian Gillan (which produced some bootlegged concerts and Sabbath renditions of Purple classic "Smoke On The Water)." The lineup is responsible for many rock 'n' roll stories that worked their way into Spinal Tap (see the individual write-up). The album is an oddity, but also a record that found a cult audience. The famous cover is also one of Sabbath's perennial T-shirt sellers.

Sabbath throughout the late '80s and early to mid '90s was a fluid entity; Iommi partnered with vocalists Glenn Hughes and Tony Martin, and rejoined Dio for Dehumanizer. Metal was shelved as Nirvana ruled the airwaves. While Iommi-only Sabbath floundered, it set up the inevitable reunion of the original four.

A succession of reunions began in 1996. The original four reunited with shows in Birmingham in 1997 and a 1999 headlining appearance at Ozzfest that made the dreams of many longtime fans who'd never seen the original lineup together come true (this writer included). There was talk of a new record, but all we got were two subpar tracks on the Reunion double album: "Psycho Man" and "Selling My Soul." Fans would wait more than a decade for most of the original lineup to get together and work on a new record.

The reunions continued. At this point Black Sabbath was big business. The Dio lineup reunited in 2007 -- called Heaven And Hell for legal reasons -- and later recorded the comeback album The Devil You Know. After Dio's death, the original four got back together but quickly fractured when Ward left due to contract dispute. Rage Against The Machine drummer Brad Wilk replaced him on 13. The move alienated a section of fans; there's even a Facebook page called "No Bill Ward, No Black Sabbath."

Trying to list every band that has been influenced by Black Sabbath or every guitarist influenced by Iommi is a task meant for Sisyphus. Yes, Sabbath created a new musical genre. Yet there is nothing completely "new" in Sabbath's sound; ultimately, it is the fullest expression of a language that began with the blues and evolved into rock music. It wasn't about what Sabbath invented as how they took readily available tools and created an art form that would be defined by volume, speed, dexterity, and darkness.

Sabbath's children are legion and ever-multiplying. In honor of their new album 13 -- released in early June -- we count down their albums from worst to best.

19. Forbidden (1995)

Forbidden was the low point for albums bearing the name Black Sabbath, featuring a questionable partnership with producer Ernie C and a guest appearance with his Body Count bandmate Ice T (trivia: Ice T has recorded songs with Sabbath, Slayer, and the death metal band Six Feet Under). Ice T is a rap legend and was fantastic on the album originally called Cop Killer (later just called Body Count) but the song "Illusion Of Power," and this entire album, are dreadful. Forbidden is an album best forgotten — and one Iommi says "should've been forbidden." Unsurprisingly, Forbidden was released before the decision to reunite the four members and rescue the name Black Sabbath from additional mediocrity. It was the last Sabbath record until 13.

19. Forbidden (1995)

Forbidden was the low point for albums bearing the name Black Sabbath, featuring a questionable partnership with producer Ernie C and a guest appearance with his Body Count bandmate Ice T (trivia: Ice T has recorded songs with Sabbath, Slayer, and the death metal band Six Feet Under). Ice T is a rap legend and was fantastic on the album originally called Cop Killer (later just called Body Count) but the song "Illusion Of Power," and this entire album, are dreadful. Forbidden is an album best forgotten — and one Iommi says "should've been forbidden." Unsurprisingly, Forbidden was released before the decision to reunite the four members and rescue the name Black Sabbath from additional mediocrity. It was the last Sabbath record until 13.

18. Tyr (1990)

You only need to read a description of Tyr to see things were headed in the wrong direction: Black Sabbath toying with Norse mythology, just a few years before a bunch of sociopathic Norwegian kids did more interesting things with their native folklore. It's a forgettable album that often sounds like Styx trying to record a full on rock opera a la Kilroy Was Here. Iommi's riffs are buried; the keyboards run ramshackle and the concept and approach were ham-handed at best. TYR is ample proof that even lord of riffs Tony Iommi makes mistakes; in his memoir he titled the chapter on this era "TYR And Tired."

18. Tyr (1990)

You only need to read a description of Tyr to see things were headed in the wrong direction: Black Sabbath toying with Norse mythology, just a few years before a bunch of sociopathic Norwegian kids did more interesting things with their native folklore. It's a forgettable album that often sounds like Styx trying to record a full on rock opera a la Kilroy Was Here. Iommi's riffs are buried; the keyboards run ramshackle and the concept and approach were ham-handed at best. TYR is ample proof that even lord of riffs Tony Iommi makes mistakes; in his memoir he titled the chapter on this era "TYR And Tired."

17. Cross Purposes (1994)

Cross Purposes was released two years after Iommi and Butler worked wonders with Dio again on the excellent Dehumanizer record. Despite Geezer's presence this is one of the lesser albums featuring Tony Martin although it's stronger than reviews would have you believe; you can't do something completely off with Iommi and Butler in the same room. Martin has appeared on bad records but is underappreciated. That said, none of the songs on Cross Purposes are memorable, even "Hand That Rocks The Cradle," which spawned one of the better '90s Sabbath videos.

17. Cross Purposes (1994)

Cross Purposes was released two years after Iommi and Butler worked wonders with Dio again on the excellent Dehumanizer record. Despite Geezer's presence this is one of the lesser albums featuring Tony Martin although it's stronger than reviews would have you believe; you can't do something completely off with Iommi and Butler in the same room. Martin has appeared on bad records but is underappreciated. That said, none of the songs on Cross Purposes are memorable, even "Hand That Rocks The Cradle," which spawned one of the better '90s Sabbath videos.

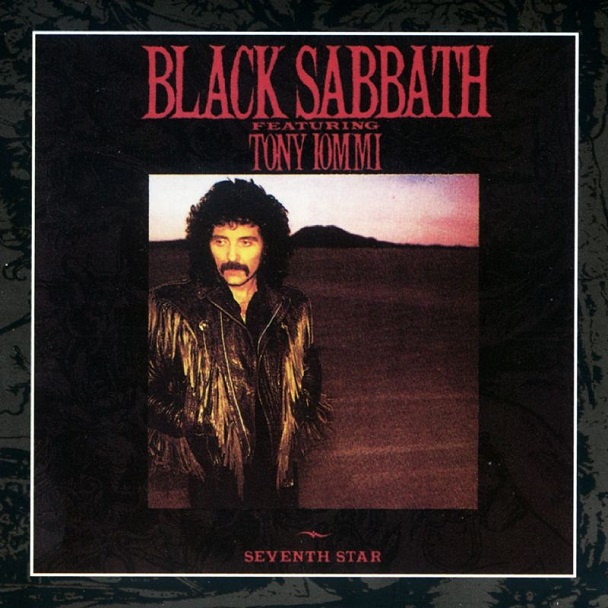

16. Seventh Star (1986)

Seventh Star, featuring vocalist Glenn Hughes, was set to become Iommi's first solo record, but label pressure from Warners forced him to release it under the name Black Sabbath. It's an interesting, albeit imperfect, listen and Hughes' only outing with the band. Since Iommi never thought Seventh Star would be called a Black Sabbath album it sounds nothing like you'd expect. Still, there are moments when Iommi and his collaborators, including keyboardist Geoff Nicholls, touch the blues and improvisational spirit that made Sabbath's debut compelling. Seventh Star shows Iommi's growth as a musician and the multiple facets of his musical prowess; he could have easily been a virtuoso bluesman had he not pursued a darker course. However, it's not nearly as compelling as earlier Black Sabbath material. In retrospect, this album would have been much better served — and better appreciated — if released solo.

16. Seventh Star (1986)

Seventh Star, featuring vocalist Glenn Hughes, was set to become Iommi's first solo record, but label pressure from Warners forced him to release it under the name Black Sabbath. It's an interesting, albeit imperfect, listen and Hughes' only outing with the band. Since Iommi never thought Seventh Star would be called a Black Sabbath album it sounds nothing like you'd expect. Still, there are moments when Iommi and his collaborators, including keyboardist Geoff Nicholls, touch the blues and improvisational spirit that made Sabbath's debut compelling. Seventh Star shows Iommi's growth as a musician and the multiple facets of his musical prowess; he could have easily been a virtuoso bluesman had he not pursued a darker course. However, it's not nearly as compelling as earlier Black Sabbath material. In retrospect, this album would have been much better served — and better appreciated — if released solo.

15. 13 (2013)

On 13, the stars seemingly aligned for what could be Sabbath's triumphant return. All four original members were initially on board. Producer Rick Rubin, who produced Slayer's benchmark Reign In Blood, was set to produce. Things started to unravel: Ward sat out on the recording because of a financial dispute (or was being difficult, depending on who you believe) and Iommi was diagnosed with lymphoma. What was supposed to be the equivalent of the Gods coming down from metal Olympus– Rubin helping the legends recapture their old sound — doesn't quite get there. Although Iommi still writes the best riffs around they don't get much support and Rage Against The Machine drummer Brad Wilk, while talented, is no replacement for Bill Ward. Ozzy sounds strangely uninspired for his first outing with Sabbath since the late 70s. Supporters of the album will be like fans that rallied to the Star Wars prequels; they are so excited to have Sabbath — or three-quarters of the band — back in their lives that they've abandoned their critical faculties. Down the road, they will realize 13 was a disappointment. Regardless, this was the first Sabbath album to ever hit the top slot in the Billboard album charts.

15. 13 (2013)

On 13, the stars seemingly aligned for what could be Sabbath's triumphant return. All four original members were initially on board. Producer Rick Rubin, who produced Slayer's benchmark Reign In Blood, was set to produce. Things started to unravel: Ward sat out on the recording because of a financial dispute (or was being difficult, depending on who you believe) and Iommi was diagnosed with lymphoma. What was supposed to be the equivalent of the Gods coming down from metal Olympus– Rubin helping the legends recapture their old sound — doesn't quite get there. Although Iommi still writes the best riffs around they don't get much support and Rage Against The Machine drummer Brad Wilk, while talented, is no replacement for Bill Ward. Ozzy sounds strangely uninspired for his first outing with Sabbath since the late 70s. Supporters of the album will be like fans that rallied to the Star Wars prequels; they are so excited to have Sabbath — or three-quarters of the band — back in their lives that they've abandoned their critical faculties. Down the road, they will realize 13 was a disappointment. Regardless, this was the first Sabbath album to ever hit the top slot in the Billboard album charts.

14. The Eternal Idol (1989)

The Eternal Idol is a hidden gem in the Sabbath catalog and a rebuke to anyone who thinks any post Dio Sabbath album was a train wreck. Some of those albums were rough but this is a keeper. Iommi sounds inspired from the beginning of the opening track "The Shining." Tony Martin's vocals are somewhat of an acquired taste on this album but if you keep listening they start to feel right. This album is clearly missing Butler or Dio's lyrical input. Sabbath is supposed to feel menacing and The Eternal Idol fall far short in that regard. Vocalist Ray Gillen was initially hired for this album; his initial Eternal Idol sessions are now available on the reissued deluxe album for comparison. The roster on this album is one of the strangest ever on a Sabbath release: Bassist Bob Daisley (best known for his work on the solo Ozzy albums) and drummer Eric Singer, who wears the Peter Criss catman makeup in later day KISS. The Eternal Idol is not without flaws but as a Sabbath excursion to power metal — and evidence of Iommi's ample chops — it remains intriguing.

14. The Eternal Idol (1989)

The Eternal Idol is a hidden gem in the Sabbath catalog and a rebuke to anyone who thinks any post Dio Sabbath album was a train wreck. Some of those albums were rough but this is a keeper. Iommi sounds inspired from the beginning of the opening track "The Shining." Tony Martin's vocals are somewhat of an acquired taste on this album but if you keep listening they start to feel right. This album is clearly missing Butler or Dio's lyrical input. Sabbath is supposed to feel menacing and The Eternal Idol fall far short in that regard. Vocalist Ray Gillen was initially hired for this album; his initial Eternal Idol sessions are now available on the reissued deluxe album for comparison. The roster on this album is one of the strangest ever on a Sabbath release: Bassist Bob Daisley (best known for his work on the solo Ozzy albums) and drummer Eric Singer, who wears the Peter Criss catman makeup in later day KISS. The Eternal Idol is not without flaws but as a Sabbath excursion to power metal — and evidence of Iommi's ample chops — it remains intriguing.

13. Never Say Die! (1978)

Never Say Die! was the least of the albums featuring the original four, often flat and uninspired. Like its predecessor Technical Ecstasy, Never Say Die! works best when Sabbath strips it down on songs like on "Johnny Blade."The keyboards, however, had become a commodity on this release. Iommi still has it; even on lesser material, he spins riff after riff that other players would be happy to create. Nonetheless, Never Say Die! is the nadir of Sabbath's original period,an album that has fans but also detractors.

13. Never Say Die! (1978)

Never Say Die! was the least of the albums featuring the original four, often flat and uninspired. Like its predecessor Technical Ecstasy, Never Say Die! works best when Sabbath strips it down on songs like on "Johnny Blade."The keyboards, however, had become a commodity on this release. Iommi still has it; even on lesser material, he spins riff after riff that other players would be happy to create. Nonetheless, Never Say Die! is the nadir of Sabbath's original period,an album that has fans but also detractors.

12. Headless Cross (1989)

Headless Cross is the high point of the Tony Martin-Tony Iommi collaboration, from the ominous "Gates of Hell" instrumental to songs like "Devil & Daughter" and "Call Of The Wild." Sabbath in the late 80s and early 90s often stumbled both on execution and delivery but Headless Cross is a record that actually felt like Sabbath: powerful, dark and louder than life. Iommi is in command here and Martin's vocals work well with the material. The best parts of it remind somewhat of Heaven And Hell, even if they never scale the heights of that album. Headless Cross showcases Martin's multifaceted vocal delivery, which is misused on some of the lesser albums from the Martin-Iommi partnership.Headless Cross was one of the times when a Iommi-only Sabbath got everything right and did justice to the weight that the name Black Sabbath carries.

12. Headless Cross (1989)

Headless Cross is the high point of the Tony Martin-Tony Iommi collaboration, from the ominous "Gates of Hell" instrumental to songs like "Devil & Daughter" and "Call Of The Wild." Sabbath in the late 80s and early 90s often stumbled both on execution and delivery but Headless Cross is a record that actually felt like Sabbath: powerful, dark and louder than life. Iommi is in command here and Martin's vocals work well with the material. The best parts of it remind somewhat of Heaven And Hell, even if they never scale the heights of that album. Headless Cross showcases Martin's multifaceted vocal delivery, which is misused on some of the lesser albums from the Martin-Iommi partnership.Headless Cross was one of the times when a Iommi-only Sabbath got everything right and did justice to the weight that the name Black Sabbath carries.

11. Technical Ecstasy (1976)

Next to Born Again, Technical Ecstasy is the oddest entry in the Sabbath catalog. The cover is an inexplicable image by design house Hipgnosis that shows two robots reproducing on an escalator. I remember staring at it and thinking it made me vaguely uncomfortable, sort of like the kid in Fight Club who sees a penis woven into a film reel. The music also causes a feeling of disconnectedness. There are some stylistic links with Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, like keyboards and orchestration. This time, the experiments don't pan out and Ozzy's voice sounds strangely muffled.What does work is the straight ahead rockers: "Back Street Kids" and "Rock 'N' Roll Doctor.""Back Street Kids" wouldn't sound out of on place on morning FM radio. "Gypsy" is a beautiful song that taps into Sab's progressive leanings.Bill Ward, who would later front his own project, made his singing debut with the song "It's Alright," later covered by Guns N' Roses. Ward's voice sounds tested and world weary.Technical Ecstasy is a far better album than many remember, even though it doesn't equal earlier efforts from the original lineup.

11. Technical Ecstasy (1976)

Next to Born Again, Technical Ecstasy is the oddest entry in the Sabbath catalog. The cover is an inexplicable image by design house Hipgnosis that shows two robots reproducing on an escalator. I remember staring at it and thinking it made me vaguely uncomfortable, sort of like the kid in Fight Club who sees a penis woven into a film reel. The music also causes a feeling of disconnectedness. There are some stylistic links with Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, like keyboards and orchestration. This time, the experiments don't pan out and Ozzy's voice sounds strangely muffled.What does work is the straight ahead rockers: "Back Street Kids" and "Rock 'N' Roll Doctor.""Back Street Kids" wouldn't sound out of on place on morning FM radio. "Gypsy" is a beautiful song that taps into Sab's progressive leanings.Bill Ward, who would later front his own project, made his singing debut with the song "It's Alright," later covered by Guns N' Roses. Ward's voice sounds tested and world weary.Technical Ecstasy is a far better album than many remember, even though it doesn't equal earlier efforts from the original lineup.

10. Dehumanizer (1992)

Whenever Black Sabbath needed to work some magic when the chips were down their mantra seemed to be: rehire Dio. It worked when Ozzy was fired for the first time, it worked in the early 90s and it worked in the aughts when they reunited with Dio as Heaven And Hell. Sabbath's third pairing with Dio and their second with drummer Vinny Appice showed how effective the Dio-Iommi partnership could be under the right circumstances. Sabbath also proved that they could be eerily prescient: one of the best songs on the album is "Computer God." It's hard to see how threatening a bunch of glorified word processors with no Internet access could be in the early 90s but roughly two decades later technology has become divinity for many. Dehumanizer includes several songs that were resurrected and given their proper due during the Heaven and Hell tour, including "After All (The Dead)." This lineup would go one more round with the excellent The Devil You Know album prompted by those wildly successful tours. It's not included because it's not called Black Sabbath, but in every other regard it's the fourth Dio/Sabbath album and an excellent addition to any Sabbath collection. Dehumanizer remains a riveting listen and a vital piece of the Sabbath discography.

10. Dehumanizer (1992)

Whenever Black Sabbath needed to work some magic when the chips were down their mantra seemed to be: rehire Dio. It worked when Ozzy was fired for the first time, it worked in the early 90s and it worked in the aughts when they reunited with Dio as Heaven And Hell. Sabbath's third pairing with Dio and their second with drummer Vinny Appice showed how effective the Dio-Iommi partnership could be under the right circumstances. Sabbath also proved that they could be eerily prescient: one of the best songs on the album is "Computer God." It's hard to see how threatening a bunch of glorified word processors with no Internet access could be in the early 90s but roughly two decades later technology has become divinity for many. Dehumanizer includes several songs that were resurrected and given their proper due during the Heaven and Hell tour, including "After All (The Dead)." This lineup would go one more round with the excellent The Devil You Know album prompted by those wildly successful tours. It's not included because it's not called Black Sabbath, but in every other regard it's the fourth Dio/Sabbath album and an excellent addition to any Sabbath collection. Dehumanizer remains a riveting listen and a vital piece of the Sabbath discography.

9. Born Again (1983)

Born Again is a flawed masterpiece. It came together after Dio and Appice left Sabbath, reportedly due to arguments about the mix of the Live Evil album (there were rumors that the pair snuck in to mix the vocals and drums higher). The back stories on the record fueled Spinal Tap and are enough for a book: the decision to have dwarves on the stage; the disastrous efforts to replicate Stonehenge for a tour, and the album cover of a hideous devil baby, which reportedly made vocalist Ian Gillan vomit. The album also birthed a few of the strangest rock videos ever recorded, featuring deformed butlers, farm animals, and drunk driving. Deep Purple vocalist Gillan was an interesting choice for a vocalist, picked as much because of his friendship with the band as for his chops. He wasn't a wailer like Ozzy and didn't have Dio's range but rather a voice suited to classic rock. It works very well on Born Again.

There are strange sounds throughout Born Again and the mix is dreadful. Earlier mixes of the album have since resurfaced. But there's no denying the power of the songs. "Trashed" is the best song ever about a late-night drinking session and a wrecked go-kart. "Disturbing The Priest" was written after aggravating their chaste next door neighbors in a rectory. There are a few songs that are expendable, like "Hot Line." But the best song — and a keeper from Sabbath's long career — is "Zero The Hero." The riff of Guns N' Roses'"Paradise City" is remarkably similar to "Zero," and was once covered by the death metal band Cannibal Corpse.Born Again is a strange album from a bizarre time, but there are plenty of things that make it a memorable listen.

9. Born Again (1983)

Born Again is a flawed masterpiece. It came together after Dio and Appice left Sabbath, reportedly due to arguments about the mix of the Live Evil album (there were rumors that the pair snuck in to mix the vocals and drums higher). The back stories on the record fueled Spinal Tap and are enough for a book: the decision to have dwarves on the stage; the disastrous efforts to replicate Stonehenge for a tour, and the album cover of a hideous devil baby, which reportedly made vocalist Ian Gillan vomit. The album also birthed a few of the strangest rock videos ever recorded, featuring deformed butlers, farm animals, and drunk driving. Deep Purple vocalist Gillan was an interesting choice for a vocalist, picked as much because of his friendship with the band as for his chops. He wasn't a wailer like Ozzy and didn't have Dio's range but rather a voice suited to classic rock. It works very well on Born Again.

There are strange sounds throughout Born Again and the mix is dreadful. Earlier mixes of the album have since resurfaced. But there's no denying the power of the songs. "Trashed" is the best song ever about a late-night drinking session and a wrecked go-kart. "Disturbing The Priest" was written after aggravating their chaste next door neighbors in a rectory. There are a few songs that are expendable, like "Hot Line." But the best song — and a keeper from Sabbath's long career — is "Zero The Hero." The riff of Guns N' Roses'"Paradise City" is remarkably similar to "Zero," and was once covered by the death metal band Cannibal Corpse.Born Again is a strange album from a bizarre time, but there are plenty of things that make it a memorable listen.

8. Mob Rules (1981)

Mob Rules was beefier, louder, and more bombastic than its predecessor, Heaven And Hell, an album that is more street than studio. Part of the new sound was a switch to Vinny Appice, who relied more on power and less on fills and creativity than Ward. Then there's the beefy production by Martin Birch. The result is a caustic but compelling listen, an album that proved the great work on Heaven And Hell wasn't a one-time fluke.

Mob Rules is an album that compels you to listen again, like Slayer's Reign In Blood would later in the decade. When I was a kid I kept this cassette tape with me and played it until it was frayed. Then I replaced it. It's a different album than Heaven And Hell, with a darker vibe. There aren't as many quiet moments; even the introduction to "The Sign Of The Southern Cross" makes you feel like you are being sucked down a well. Dio's voice is again a benchmark and you can see the stepping stones from this album to his solo career and songs like "Holy Diver." The first round of the Dio/Sabbath lineup would end after this record but Mob Rules has stood the test of time.

8. Mob Rules (1981)

Mob Rules was beefier, louder, and more bombastic than its predecessor, Heaven And Hell, an album that is more street than studio. Part of the new sound was a switch to Vinny Appice, who relied more on power and less on fills and creativity than Ward. Then there's the beefy production by Martin Birch. The result is a caustic but compelling listen, an album that proved the great work on Heaven And Hell wasn't a one-time fluke.

Mob Rules is an album that compels you to listen again, like Slayer's Reign In Blood would later in the decade. When I was a kid I kept this cassette tape with me and played it until it was frayed. Then I replaced it. It's a different album than Heaven And Hell, with a darker vibe. There aren't as many quiet moments; even the introduction to "The Sign Of The Southern Cross" makes you feel like you are being sucked down a well. Dio's voice is again a benchmark and you can see the stepping stones from this album to his solo career and songs like "Holy Diver." The first round of the Dio/Sabbath lineup would end after this record but Mob Rules has stood the test of time.

7. Sabotage (1975)

Sabotage was the last great record from the original Sabbath lineup before drugs, squabbles, and petty feuds sent them into a tailspin and ended with the eventual dismissal of Osbourne.The abiding vibe on Sabotage is the feeling of unraveling. The means might be mental illness, delusions of grandeur, or enemies posing as friends. There are abundant references to schizophrenia, madness, and insanity.

On their sixth record, Sabbath perfectly captured a sense of dissolution, of a fragmented self. Sabotage is perhaps their most autobiographical record, a musical documentary of a time when the band beginning to unravel due to substance abuse, financial pressures, and frayed relationships.

The cover is almost as inexplicable as the sword and shield bearing nut on Paranoid; Ward is wearing his wife's pajamas; Ozzy looks like he rolled out of an opium den and Iommi appears to be a car salesman. The contents, however, are vintage Sabbath. "Symptom Of The Universe" is one of the gems of the catalog and contains a classic Iommi riff. "Am I Going Insane" sounds like easy listening based on earlier Sabbath material but ends with screams you might hear in a nuthouse. It's a deceptive lull.The centerpiece of the album is "The Writ." It's not about the occult, drugs, or Satan, but rather about getting fucked over by greedy producers and lawyers. The angry missive was an appropriate exclamation point;Sabotage was the last time the band captured magic untilDio joined their ranks five years later.

7. Sabotage (1975)

Sabotage was the last great record from the original Sabbath lineup before drugs, squabbles, and petty feuds sent them into a tailspin and ended with the eventual dismissal of Osbourne.The abiding vibe on Sabotage is the feeling of unraveling. The means might be mental illness, delusions of grandeur, or enemies posing as friends. There are abundant references to schizophrenia, madness, and insanity.

On their sixth record, Sabbath perfectly captured a sense of dissolution, of a fragmented self. Sabotage is perhaps their most autobiographical record, a musical documentary of a time when the band beginning to unravel due to substance abuse, financial pressures, and frayed relationships.

The cover is almost as inexplicable as the sword and shield bearing nut on Paranoid; Ward is wearing his wife's pajamas; Ozzy looks like he rolled out of an opium den and Iommi appears to be a car salesman. The contents, however, are vintage Sabbath. "Symptom Of The Universe" is one of the gems of the catalog and contains a classic Iommi riff. "Am I Going Insane" sounds like easy listening based on earlier Sabbath material but ends with screams you might hear in a nuthouse. It's a deceptive lull.The centerpiece of the album is "The Writ." It's not about the occult, drugs, or Satan, but rather about getting fucked over by greedy producers and lawyers. The angry missive was an appropriate exclamation point;Sabotage was the last time the band captured magic untilDio joined their ranks five years later.

6. Volume 4 (1972)

Volume 4 is Sabbath's ode to excess and bacchanal, the Birmingham four reinvented through Los Angeles haze. Sabbath was knee-deep in cocaine at the time (for evidence, just check the infamous liner-notes thank you to the great COKE-cola company of Los Angeles). "Snowblind" — one of Sabbath's greatest songs — contains not-so-subtle whispers of "cocaine" from Osbourne.

There's a festive feel to part of the album and tracks like "Cornucopia." But there are also hints of loss and regret, like on the powerful track "Wheel Of Confusion." Themes of disillusionment course through Volume 4; it seems like Sabbath's partying ways and touring excesses were catching up. They were dissatisfied with preachers, leaders, literally anyone offering answers or a path. The only answer, ultimately, was to be found inside.

Just like in life, the party must eventually end, and Volume 4 also hints at the flipside — that "every day just comes and goes/ life is one big overdose." It's appropriate that Ozzy re-recorded the ballad "Changes" with his daughter Kelly during the Hollywood period borne by the television show The Osbournes; Volume 4 is when a starstruck Sabbath was able to create something lasting out of sudden fame and accompanying disillusionment.

6. Volume 4 (1972)

Volume 4 is Sabbath's ode to excess and bacchanal, the Birmingham four reinvented through Los Angeles haze. Sabbath was knee-deep in cocaine at the time (for evidence, just check the infamous liner-notes thank you to the great COKE-cola company of Los Angeles). "Snowblind" — one of Sabbath's greatest songs — contains not-so-subtle whispers of "cocaine" from Osbourne.

There's a festive feel to part of the album and tracks like "Cornucopia." But there are also hints of loss and regret, like on the powerful track "Wheel Of Confusion." Themes of disillusionment course through Volume 4; it seems like Sabbath's partying ways and touring excesses were catching up. They were dissatisfied with preachers, leaders, literally anyone offering answers or a path. The only answer, ultimately, was to be found inside.

Just like in life, the party must eventually end, and Volume 4 also hints at the flipside — that "every day just comes and goes/ life is one big overdose." It's appropriate that Ozzy re-recorded the ballad "Changes" with his daughter Kelly during the Hollywood period borne by the television show The Osbournes; Volume 4 is when a starstruck Sabbath was able to create something lasting out of sudden fame and accompanying disillusionment.

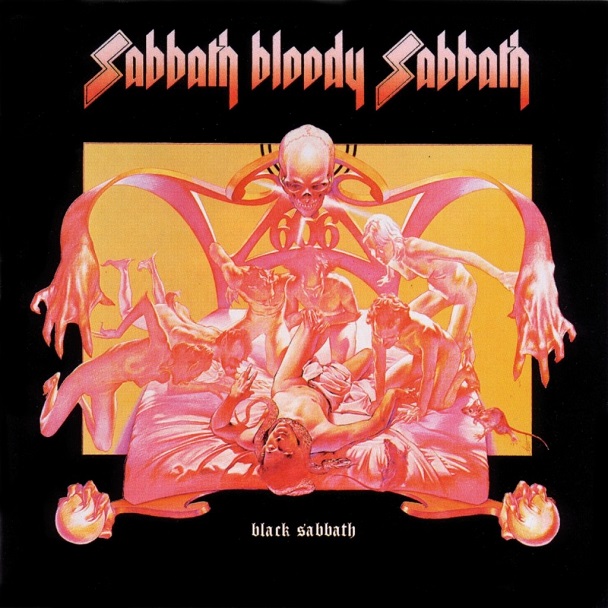

5. Sabbath Bloody Sabbath (1973)

Sabbath Bloody Sabbath is the band's progressive 70s album, a masterstroke that took advantage of bigger budgets and increased options. Instead of succumbing to sonic excess, Sabbath was able to harness studio trickery to serve their needs. They lost none of their ferocity: listen to the riff on the eponymous title track and the angry lyrics, "The people who have crippled you/ You want to see them burn … Fill your head all full of lies/ You bastards!"

Sabbath Bloody Sabbath started when the band had seemingly run out of ideas after their drug-filled stay in Los Angeles. They returned to the English countryside and holed up in a castle that was reportedly haunted. Then, they started exploring. The biggest changes were the addition of Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman, who is present on many tracks, and orchestral arrangements. The keyboards don't dilute the heaviness; if anything, they accentuate it. The cover art by Drew Struzan (who later illustrated Indiana Jones posters) was the stuff of millions of back patches and posters. Sabbath Bloody Sabbath made the band look more "evil" that they really were.

Despite the ominous cover art of nocturnal demons, Sabbath Bloody Sabbath is ultimately an album about the vagaries of life that even includes a song about DNA ("Spiral Architect.") Still strange and riveting after nearly four decades, it's a landmark in the band's musical exploration and growth.

5. Sabbath Bloody Sabbath (1973)

Sabbath Bloody Sabbath is the band's progressive 70s album, a masterstroke that took advantage of bigger budgets and increased options. Instead of succumbing to sonic excess, Sabbath was able to harness studio trickery to serve their needs. They lost none of their ferocity: listen to the riff on the eponymous title track and the angry lyrics, "The people who have crippled you/ You want to see them burn … Fill your head all full of lies/ You bastards!"

Sabbath Bloody Sabbath started when the band had seemingly run out of ideas after their drug-filled stay in Los Angeles. They returned to the English countryside and holed up in a castle that was reportedly haunted. Then, they started exploring. The biggest changes were the addition of Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman, who is present on many tracks, and orchestral arrangements. The keyboards don't dilute the heaviness; if anything, they accentuate it. The cover art by Drew Struzan (who later illustrated Indiana Jones posters) was the stuff of millions of back patches and posters. Sabbath Bloody Sabbath made the band look more "evil" that they really were.

Despite the ominous cover art of nocturnal demons, Sabbath Bloody Sabbath is ultimately an album about the vagaries of life that even includes a song about DNA ("Spiral Architect.") Still strange and riveting after nearly four decades, it's a landmark in the band's musical exploration and growth.

4. Heaven And Hell (1980)

"Oh no/ Here it comes again." The first line of "Neon Knights" could be referring to Black Sabbath. Their career was waning after two lackluster albums with Osbourne. Heaven And Hell was their rebirth. For many kids who grew up in the 80s it was their introduction to Black Sabbath before they worked their way back through the catalog.

When Osbourne was fired, Sabbath teamed with former Elf and Rainbow frontman Ronnie James Dio. It was an instant match. Heaven And Hell doesn't just rank among the best Sabbath records; it's one of the best metal releases ever. Dio's voice fit Iommi's playing and Sabbath's style perfectly and his range allowed Iommi, Butler, and a succession of drummers (Ward and then Vinnie Appice) to explore directions not possible with Osbourne.

The lyrics changed; there's more fantasy here. But Sabbath was still a band about big ideas: "Heaven And Hell" is about how fickle life is, offering both and pleasure and pain, and "Children Of The Sea" is an environmental plea well before the term "climate change" was introduced. Dio's voice throughout is majestic — it might be the best performance in a career that pushed what was possible for metal vocals (along with Judas Priest's Rob Halford and Iron Maiden's Bruce Dickinson).

Iommi's riffs on Heaven And Hell stand next to those on the first four Sabbath albums, and his soloing is fluid. Ward played on the record but reportedly was so mired in alcoholism that he can't remember recording it. Instinct must have kicked in because his playing here is, again, amazing. Heaven And Hell is a mandatory album from a retooled Sabbath lineup.

4. Heaven And Hell (1980)

"Oh no/ Here it comes again." The first line of "Neon Knights" could be referring to Black Sabbath. Their career was waning after two lackluster albums with Osbourne. Heaven And Hell was their rebirth. For many kids who grew up in the 80s it was their introduction to Black Sabbath before they worked their way back through the catalog.

When Osbourne was fired, Sabbath teamed with former Elf and Rainbow frontman Ronnie James Dio. It was an instant match. Heaven And Hell doesn't just rank among the best Sabbath records; it's one of the best metal releases ever. Dio's voice fit Iommi's playing and Sabbath's style perfectly and his range allowed Iommi, Butler, and a succession of drummers (Ward and then Vinnie Appice) to explore directions not possible with Osbourne.

The lyrics changed; there's more fantasy here. But Sabbath was still a band about big ideas: "Heaven And Hell" is about how fickle life is, offering both and pleasure and pain, and "Children Of The Sea" is an environmental plea well before the term "climate change" was introduced. Dio's voice throughout is majestic — it might be the best performance in a career that pushed what was possible for metal vocals (along with Judas Priest's Rob Halford and Iron Maiden's Bruce Dickinson).

Iommi's riffs on Heaven And Hell stand next to those on the first four Sabbath albums, and his soloing is fluid. Ward played on the record but reportedly was so mired in alcoholism that he can't remember recording it. Instinct must have kicked in because his playing here is, again, amazing. Heaven And Hell is a mandatory album from a retooled Sabbath lineup.

3. Black Sabbath (1970)

Recorded on a whim, Black Sabbath's debut is the stuff of legend. First, there's the unknown woman who posed by the mill on the front cover (she's never been located — was she really a witch?). Then, there's the upside down cross and the poem inside the vinyl edition. Most importantly, there's the music.

Sabbath's debut was, in many respects, a hybrid blues album — I wrote about this before, during the 40th anniversary of the record three years ago. I stand by the assessment. Sabbath was still a jam band developing their craft by doing longstanding house gigs. They weren't even sure they were getting anywhere until they were offered a record contract. This album was cranked out in days.

Their debut reflects their blues roots. The opener is a Sabbath perennial. As mentioned in every documentary ever produced on metal history, "Black Sabbath" liberally uses the minor third progression, i.e. the Devil's tritone, an interlude avoided during medieval times. "The Wizard" is very bluesy with a memorable harmonica riff. "NIB" led to decades of fans and critics assigning meanings to Sabbath songs that simply aren't there. It's not "Nativity In Black" as many would suggest — just like AC/DC didn't mean "Against Christ/Devil's Children." AC/DC was referring to a power source and "NIB" was a reference to Bill Ward's "nibby" beard, which was shaped like a pen nib. The song is a blues paean to lost love, narrated by Lucifer.

Side B runs together like a long song. It feels like a slow horror story that unfolds and engulfs; it gives you a taste of what early Sabbath might have sounded like live. "Sleeping Village" sets the stage: placid, benevolent. A Jew's harp conjures visions of small towns, mist, and ghostly apparitions. "Warning" wasn't a Sabbath original but rather a reinvention of a song by Aynsley Dunbar that let Iommi show his genius improvisational skills. Sabbath didn't write "Warning" but they certainly own it.

Black Sabbath is Sabbath at their most primal and musically loosest. The album was recorded in shirt order and some of it appears to be improvised. That's what makes it such a valuable historical record and engrossing listen: this is what Sabbath sounded like in the earliest days, before stadium tours, wealth, and distractions impaired their vision.

3. Black Sabbath (1970)

Recorded on a whim, Black Sabbath's debut is the stuff of legend. First, there's the unknown woman who posed by the mill on the front cover (she's never been located — was she really a witch?). Then, there's the upside down cross and the poem inside the vinyl edition. Most importantly, there's the music.

Sabbath's debut was, in many respects, a hybrid blues album — I wrote about this before, during the 40th anniversary of the record three years ago. I stand by the assessment. Sabbath was still a jam band developing their craft by doing longstanding house gigs. They weren't even sure they were getting anywhere until they were offered a record contract. This album was cranked out in days.

Their debut reflects their blues roots. The opener is a Sabbath perennial. As mentioned in every documentary ever produced on metal history, "Black Sabbath" liberally uses the minor third progression, i.e. the Devil's tritone, an interlude avoided during medieval times. "The Wizard" is very bluesy with a memorable harmonica riff. "NIB" led to decades of fans and critics assigning meanings to Sabbath songs that simply aren't there. It's not "Nativity In Black" as many would suggest — just like AC/DC didn't mean "Against Christ/Devil's Children." AC/DC was referring to a power source and "NIB" was a reference to Bill Ward's "nibby" beard, which was shaped like a pen nib. The song is a blues paean to lost love, narrated by Lucifer.

Side B runs together like a long song. It feels like a slow horror story that unfolds and engulfs; it gives you a taste of what early Sabbath might have sounded like live. "Sleeping Village" sets the stage: placid, benevolent. A Jew's harp conjures visions of small towns, mist, and ghostly apparitions. "Warning" wasn't a Sabbath original but rather a reinvention of a song by Aynsley Dunbar that let Iommi show his genius improvisational skills. Sabbath didn't write "Warning" but they certainly own it.

Black Sabbath is Sabbath at their most primal and musically loosest. The album was recorded in shirt order and some of it appears to be improvised. That's what makes it such a valuable historical record and engrossing listen: this is what Sabbath sounded like in the earliest days, before stadium tours, wealth, and distractions impaired their vision.

2. Master Of Reality (1971)

Master Of Reality is the album that birthed the entire doom and stoner genres, from the marijuana loving ode "Sweet Leaf" to the warm, earthy tone and analog production that influenced bands like Saint Vitus, Electric Wizard, Cathedral, The Gates Of Slumber, Orchid, and countless others.

Master Of Reality is an interesting title choice considering that the album is all about abandoning reality. The sound is a womb or a cocoon; it muffles the outside world so you can find comfort elsewhere, whether through drugs, delusion, or even faith.

Ward and Butler dialed it back on Master and worked in tandem with Iommi in service of the riff. It's not that their playing is minimized; it's that they formed a bulwark. There's also not as much playfulness or improvisation on Master as there was on the debut or Paranoid; rather, you have Sabbath working together for a single, devastating effect.

Master Of Reality is an album that helps you get lost, the record spinning in the background as a teenager tentatively smokes their first joint. "Sweet Leaf" — a title taken from a description of a cigarette named Sweet Aftons — is about the wonder of marijuana and accessing your third eye; "After Forever" urges listeners to find hope in God ("God is the only way to love") and "Into The Void" is about leaving a desolate Earth behind for new worlds. Perhaps the madness of Vietnam led to the rampant escapism on Master, and the suffocating feel. Master Of Reality has been called a Christian album and that might be an exaggeration. You could say that Master Of Reality is a dystopian album, one where Sabbath looks at the world we're trapped in and pines for something better.

Most critics savaged Master Of Reality, including Lester Bangs:

The thick, plodding, almost arrhythmic steel wool curtains of sound the group is celebrated and reviled for only appear in their classical state of excruciating slowness on two tracks, "Sweet Leaf" and "Lord of This World," and both break into driving jams that are well worth the wait. Which itself is no problem once you stop thinking about how bored you are and just let it filter down your innards like a good bottle of Romilar. Rock 'n' roll has always been noise, and Black Sabbath have boiled that noise to its resinous essence. Did you expect bones to be anything else but rigid?

Bangs was wrong. The message — and the music — have lasted. Master Of Reality is, in some ways, strangely hopeful. Mountain Goats frontman John Darnielle wrote a novel as part of the 33 1/3 series about an institutionalized teen that finds some hope and connection in Master Of Reality. That an entire novel could be written in tribute to an album speaks to how Master Of Reality created a universe in the minds and hearts of listeners.

2. Master Of Reality (1971)

Master Of Reality is the album that birthed the entire doom and stoner genres, from the marijuana loving ode "Sweet Leaf" to the warm, earthy tone and analog production that influenced bands like Saint Vitus, Electric Wizard, Cathedral, The Gates Of Slumber, Orchid, and countless others.

Master Of Reality is an interesting title choice considering that the album is all about abandoning reality. The sound is a womb or a cocoon; it muffles the outside world so you can find comfort elsewhere, whether through drugs, delusion, or even faith.

Ward and Butler dialed it back on Master and worked in tandem with Iommi in service of the riff. It's not that their playing is minimized; it's that they formed a bulwark. There's also not as much playfulness or improvisation on Master as there was on the debut or Paranoid; rather, you have Sabbath working together for a single, devastating effect.

Master Of Reality is an album that helps you get lost, the record spinning in the background as a teenager tentatively smokes their first joint. "Sweet Leaf" — a title taken from a description of a cigarette named Sweet Aftons — is about the wonder of marijuana and accessing your third eye; "After Forever" urges listeners to find hope in God ("God is the only way to love") and "Into The Void" is about leaving a desolate Earth behind for new worlds. Perhaps the madness of Vietnam led to the rampant escapism on Master, and the suffocating feel. Master Of Reality has been called a Christian album and that might be an exaggeration. You could say that Master Of Reality is a dystopian album, one where Sabbath looks at the world we're trapped in and pines for something better.

Most critics savaged Master Of Reality, including Lester Bangs:

The thick, plodding, almost arrhythmic steel wool curtains of sound the group is celebrated and reviled for only appear in their classical state of excruciating slowness on two tracks, "Sweet Leaf" and "Lord of This World," and both break into driving jams that are well worth the wait. Which itself is no problem once you stop thinking about how bored you are and just let it filter down your innards like a good bottle of Romilar. Rock 'n' roll has always been noise, and Black Sabbath have boiled that noise to its resinous essence. Did you expect bones to be anything else but rigid?

Bangs was wrong. The message — and the music — have lasted. Master Of Reality is, in some ways, strangely hopeful. Mountain Goats frontman John Darnielle wrote a novel as part of the 33 1/3 series about an institutionalized teen that finds some hope and connection in Master Of Reality. That an entire novel could be written in tribute to an album speaks to how Master Of Reality created a universe in the minds and hearts of listeners.

1. Paranoid (1970)

Paranoid is the album where heavy metal truly began, the Genesis moment for the genre. Sabbath was still in a transitional mode with their debut, shedding their blues skin to become a band that changed history. Paranoid is where Sabbath came into their own and wrote songs for the ages.

The occult flavorings of their debut — which worked well paired with blues — are abandoned for social commentary. "War Pigs" starts with the sound of sirens; in the ensuing decades, almost every metal band has used a siren or battle noises to open songs about war. "War Pigs" was initially called "Walpurgis" but changed at the request of label executives. It's a critique of foreign policy during Vietnam, as biting as protest songs like "Fortunate Son" but more graphic. Generals are equated with malevolent sorcerers: "Evil minds that plot destruction/sorcerers of death's construction."

At points, the band appears to be headed in different directions but it all gloriously comes together; Iommi plays a classic riff; Ward is at his jazzy best; Butler's bass oozes into the spaces and cracks and Ozzy's voice sounds ominous. The musicianship, particularly the rhythm section, is awe-inspiring; listen to the interplay between the big three, especially the musical section closing the final two minutes of "War Pigs." It's music that still gives me goose bumps decades after I first heard it.

There are plenty of riches on Paranoid, an influential song everywhere you look. "Planet Caravan" — a psychedelic, extraterrestrial trip with a lover — is undoubtedly a favorite of contemporary bands that aim for a proto-70s sound: Uncle Acid And The Deadbeats, Ghost B.C., Purson and The Devil's Blood. "Electric Funeral" is eerie, and Butler and Ward flirt with jazz on "Hand Of Doom," a candid view of addiction and a bit of an epilogue to "War Pigs." The song is about the soldier who makes it back from war forever broken: "First it was the bomb, Vietnam napalm/ Disillusioning, you put the needle in."

The album's eponymous song was initially a throwaway, something Iommi thought of that ended up as Sabbath's first single and their encore, much like Keith Richards stumbled across "Satisfaction." It became their biggest hit and the one of the two songs most non-Sabbath fans know. The second song is "Iron Man." In the 80s the pro wrestling tag team Road Warriors used it as a ring entrance; recently, it closed out the first film in the Iron Man franchise. It's about an Avenger but not the good kind; it's a story about rejection, spite, and revenge. A marching band cadence drives the song to a furious close. "Fairies Wear Boots" has been assigned more meanings than a Shakespeare play but it's simply about a tussle with skinheads.

I talked recently with a friend who was tired of Paranoid. Like the early Led Zeppelin albums, he said he'd played it so many times that he couldn't hear it again. I encouraged him to revisit it. Paranoid is the album where everything happened for Sabbath, all at once. Four decades later, it's as fresh and relevant as ever, not just the most important Sabbath record but a musical benchmark of the 20th century.

1. Paranoid (1970)

Paranoid is the album where heavy metal truly began, the Genesis moment for the genre. Sabbath was still in a transitional mode with their debut, shedding their blues skin to become a band that changed history. Paranoid is where Sabbath came into their own and wrote songs for the ages.

The occult flavorings of their debut — which worked well paired with blues — are abandoned for social commentary. "War Pigs" starts with the sound of sirens; in the ensuing decades, almost every metal band has used a siren or battle noises to open songs about war. "War Pigs" was initially called "Walpurgis" but changed at the request of label executives. It's a critique of foreign policy during Vietnam, as biting as protest songs like "Fortunate Son" but more graphic. Generals are equated with malevolent sorcerers: "Evil minds that plot destruction/sorcerers of death's construction."

At points, the band appears to be headed in different directions but it all gloriously comes together; Iommi plays a classic riff; Ward is at his jazzy best; Butler's bass oozes into the spaces and cracks and Ozzy's voice sounds ominous. The musicianship, particularly the rhythm section, is awe-inspiring; listen to the interplay between the big three, especially the musical section closing the final two minutes of "War Pigs." It's music that still gives me goose bumps decades after I first heard it.

There are plenty of riches on Paranoid, an influential song everywhere you look. "Planet Caravan" — a psychedelic, extraterrestrial trip with a lover — is undoubtedly a favorite of contemporary bands that aim for a proto-70s sound: Uncle Acid And The Deadbeats, Ghost B.C., Purson and The Devil's Blood. "Electric Funeral" is eerie, and Butler and Ward flirt with jazz on "Hand Of Doom," a candid view of addiction and a bit of an epilogue to "War Pigs." The song is about the soldier who makes it back from war forever broken: "First it was the bomb, Vietnam napalm/ Disillusioning, you put the needle in."

The album's eponymous song was initially a throwaway, something Iommi thought of that ended up as Sabbath's first single and their encore, much like Keith Richards stumbled across "Satisfaction." It became their biggest hit and the one of the two songs most non-Sabbath fans know. The second song is "Iron Man." In the 80s the pro wrestling tag team Road Warriors used it as a ring entrance; recently, it closed out the first film in the Iron Man franchise. It's about an Avenger but not the good kind; it's a story about rejection, spite, and revenge. A marching band cadence drives the song to a furious close. "Fairies Wear Boots" has been assigned more meanings than a Shakespeare play but it's simply about a tussle with skinheads.

I talked recently with a friend who was tired of Paranoid. Like the early Led Zeppelin albums, he said he'd played it so many times that he couldn't hear it again. I encouraged him to revisit it. Paranoid is the album where everything happened for Sabbath, all at once. Four decades later, it's as fresh and relevant as ever, not just the most important Sabbath record but a musical benchmark of the 20th century.