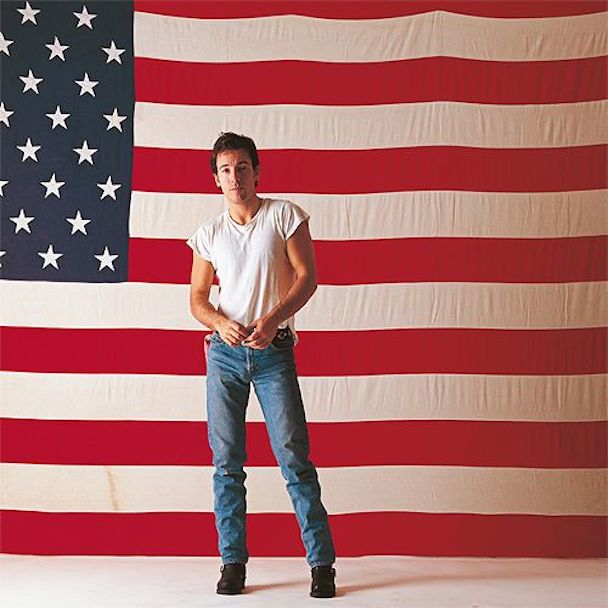

For you to remember the first time you heard Born In The U.S.A., you have to be above a certain age. It's just one of those albums. Once it was out there, it was ubiquitous. That tends to happen when you produce seven top ten singles from one album, or when a record goes platinum, let alone fifteen times over. The latter distinction means that Born In The U.S.A. sold about 15 million copies in America, a number that seems like total and complete fantasy compared to the anemic record industry of today, and one that ranks it within the top twenty or so highest selling albums, ever, in this country. This is not the kind of situation where you are still able to hear a record entirely on its own original terms, with remotely fresh ears. Even if you somehow all your life avoided hearing its title track, or "Dancing In The Dark," or "Glory Days," Born In The U.S.A. is the sort of work that, by virtue of its sheer magnitude and inevitable overexposure, comes with a whole lot of years of baggage down the line.

As of today, that would be thirty years of baggage, to be exact. Three decades on, Born In The U.S.A. has a shifting and at times conflicted legacy. In pop history, it's simple enough -- it's one of the defining records of the '80s, the one that jettisoned Springsteen to true superstar status. It's one of those albums that's never hard to find on a rack at Target or whatever, next to Thriller or Dark Side Of The Moon or Metallica. Those albums that I guess somebody somewhere will always feel like buying, the sort of stuff that's never really out of style because it's at such a level as to be beyond trends altogether. In Springsteen terms, it gets a little more complicated. Born In The U.S.A. is the Springsteen album for a certain generation of fans, and something else for those who came before or after. Every now and then I'll talk to an older fan who still grimaces at memories of Born In The U.S.A. as the album where Bruce got too big, too pop, perhaps even sold out -- if that's still a thing you can really do when you were already on the covers of Newsweek and Time in the same week a decade prior. They'll value the preceding six albums in a different way, maybe considering them more authentic. With a career as long and varied as Springsteen's you're bound to get those sorts of divides in a fanbase. Even something as widely beloved as "Backstreets" has been played frequently enough at Springsteen's shows that it's someone's holy moment and someone else's cue to go buy another beer. The dividing line always struck me as a bit more severe with Born In The U.S.A. tracks, though. Maybe you're enraptured when "Dancing In The Dark" inevitably pops up in the encore, maybe you head to the parking lot early. (But if you're the latter, I'm not sure we can be friends.)

Before we get too far down this rabbithole, it might be necessary to issue a disclaimer. I'm already on record, in a few places, about the extent of my Springsteen fandom, and the resulting amount of thought I put into his music. It's only in the last year or two, however, where I've begun to listen to Born In The U.S.A. more than any of this other work. I don't know what would be in second place, but it isn't close. There are days when it's my favorite Springsteen album. There are days when I think it's a perfect album, and other days when I'm a bit more sensible and realize that if "My Love Will Not Let You Down" had taken the place of "Cover Me," and if "Janey Don't You Lose Heart" had replaced "Glory Days," then it would've been perfect. (And, still, there are other days where I realize those maybe still wouldn't fit, even if they're brilliant.) And then, just about everyday, "Dancing In The Dark" is pretty much my favorite song ever. What I'm getting at here is that we're dealing with a bias on my part.

But, more importantly, I'm also getting at the fact that I'm one of those Springsteen fans who grew up with Born In The U.S.A. as something that was just in the air, the most ever-present material from an ever-present artist, and it's only in recent years where I've started to get truly obsessed with the thing, where I've learned to find personal resonance in an album that's too easy to take for granted due to its inherent ubiquity. The weird thing about an album so readily ranked in the "Classic" category by every other rock retrospective of one form or another, is that people can just start to think of it as This Thing That Happened, a piece of work from some distant time and place that has little meaning to them. This is the territory in which an album like Born In The U.S.A., against most logical expectations, could become underrated.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Back around the time Springsteen released Magic in 2007, he was well into a career resurgence following a mixed bag of a decade in the '90s. There were many factors to this, but one of them was that he'd attained a certain hipness in the '00s; as Stephen M. Deusner put it in his review of Magic, Springsteen had replaced Brian Wilson as the "indie ideal."

Bands like the Gaslight Anthem, the Hold Steady, and the Killers bore the influence sonically, where others like the National and the Arcade Fire were perhaps more so thematic descendants. Without fail, when people talk about Springsteen's influence on pockets of this century's generation of indie-rock, it's easiest to draw the line back to Darkness On The Edge Of Town or Nebraska (especially in the case of Dirty Beaches).

Born In The U.S.A. gets a little less credit, but at times it feels like perhaps the most important Springsteen record when it comes to newer artists being influenced by his work. Given the age of some of these musicians, this is the one that would've been new when they were kids, just getting into music; chances are, it was the formative one. They would've been the young fans for whom this was their Springsteen album. Before they went all Sandinista! on Reflektor, Arcade Fire's anthemic qualities seemed more in the lineage of Born In The U.S.A.-era Bruce, the themes of The Suburbs a mash-up of stuff like "My Hometown" and "Downbound Train" with Darkness and The River. Tellingly, when Win Butler chose his fourteen favorite Springsteen songs for Rolling Stone in 2010, most of them were from the '80s. Butler might've gone onstage to play Nebraska's "State Trooper" with the man himself, but when it came time for Arcade Fire to cover the Boss, they chose "Born In The U.S.A.." At this point, "I'm On Fire" seems destined to live on as a standard of sorts. You've got everyone from Mumford & Sons to Chromatics covering it. Gaslight Anthem frontman Brian Fallon, long the Springsteen acolyte, has been known to perform it solo, while his band's own "High Lonesome" quotes/references the song.

As of late, the War On Drugs might be leading the pack in terms of indie-rock's debt to Springsteen. Any cursory listen to stuff like "Baby Missiles," or material from this year's Lost In The Dream -- particularly "Burning" -- most evokes the synth-y roots rock of Born In The U.S.A. (Sometimes I wonder whether Adam Granduciel has actually been listening to Born In The U.S.A. outtake demos like these.) On his So Outta Reach EP, Granduciel's former bandmate Kurt Vile did a stellar version of "Downbound Train" that approximates what might've happened if Dinosaur Jr. were big fans of the Boss.

There are plenty examples of contemporary musicians looking elsewhere in Springsteen's catalog (the National covering "Mansion On The Hill," the Hold Steady doing "Atlantic City"), but I'm not trying to say Darkness or Nebraska don't loom large, because they do. The point here is that Born In The U.S.A. is somewhat sidelined in the conversation even though it has a fundamental presence in the music of these artists. It's not exactly hard to understand why. That same ubiquity I had to work my way into is simply prohibitive to other would-be Springsteen fans. Where Nebraska's bleak, lo-fi quality is a logical entry point for a younger, more indie-oriented listener, Born In The U.S.A. is saddled with a few potential deal-breakers. The production is exceedingly '80s, and not necessarily in a way of "this synthesizer sound is really cool and would become very popular in Brooklyn in 2008-2010," but more like "This just sounds old." Or, perhaps even worse, some of the synths have a surprisingly cheap sound to them that could hinder songs like "Bobby Jean" or "Dancing In The Dark" if a listener is prone to find these kinds of tones cheesy. Maybe the most damning quality is that this is the album with famous songs like "Glory Days," which isn't too many steps removed from artists like John Mellencamp, which makes it easy to lump Springsteen in with those lame heartland rockers of the time, even this many years down the road.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Actually, the most damning quality is probably the song "Born In The U.S.A." itself. It seems to represent some unlikeable quality about Springsteen to people. I had a friend in college who loved Nebraska, was totally unaware that Springsteen had also written "Born In The U.S.A.," and was totally disgusted at this revelation and demanded to not know anymore, lest I ruin Nebraska for her. Its bombastic qualities can be hard to get past, I suppose; it's only recently that it's become one of my favorite tracks on the album. But, amazingly, there still seem to be people who interpret this as some sort of jingoistic anthem, or at the very least some hollow triumphant rave-up, when it of course has a lot more going on. The same qualities that might turn off someone who just hears it as an obnoxious patriotic song from Reagan's America are the same that keep it around as the sort of song that can cranked out in a baseball stadium. It can be played over and over to large gatherings of people who may not really care about music, because it's so famous and overexposed that nobody will get overly mad or happy about it, which doesn't necessarily make it the sort of thing a new listener would be eager to engage with. And as the meaning of the song subsides into historical footnotes (though it's not hard to transpose its lyrics to our own wars in Afghanistan and Iraq), these qualities are only made worse.

Which, I suppose, fair enough: I'm a firm believer than once you put a piece of art out into the world, it ceases being totally yours, and how it's received and interpreted becomes as much a part of its story as the original intent. But, I mean, still -- the lyrics of "Born In The U.S.A." are very, very direct and it's hard to imagine people in a time as media-savvy as ours still hearing that big chorus and missing the ironic undercut of the whole thing. It's there musically, too. "Born In The U.S.A." exists in a Nebraska-esque demo from before Springsteen decided to pursue a new rock record instead. It's every bit as haunting as you'd expect from the preceding album's tone, and it sounds very little like the finished product. (For a much more in-depth breakdown of the song's complicated origins, check out Mark Richardson's post from the collaborative Bruce Springsteen One Week//One Band we both participated in last year.) Even with Springsteen's style generally falling squarely in the "earnestness" column, I can't help but hear the over-the-top anthemic qualities of "Born In The U.S.A." as a mechanism to pull out the song's dark roots and make them that much worse. He was fully aware of what he was doing at this point. When Springsteen sings a lyric like "I'm a cool rocking daddy in the U.S.A." over this backbeat, but surrounded by these lyrics, it's difficult to see how the phrase "Born In The U.S.A." could be misinterpreted as anything but the disgust it represented. The synths sound queasy themselves, especially in the song's ride-out, striking a dissonance that sums up the distance between the pride supposedly evoked in the song's title and the story it tells.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

There are a lot of other places on Born In The U.S.A. that also don't immediately reveal their darkness. To return briefly to the argument I made last year in the Springsteen Counting Down, one of the reasons Born In The U.S.A. is so great, one of the reasons it remains one of his most important albums, is that it's the one where he mingles realism and romanticism the most deftly. "Dancing In The Dark" is an infectious pop song, but most of its lyrics relate desperation: "There's something happening somewhere/Baby, I just know that there is," one of those perfectly Springsteen-esque sentiments. The story in "Dancing In The Dark" is based in the same kind of realities as "Downbound Train" or "Working On The Highway," or of songs before any of them on The River and Darkness, but the tone is one of yearning. There's just that much more amount of gloss, just that little bit of measured romanticism let in.

That combination is why there's a strong case to be made for Born In The U.S.A. being the quintessential Springsteen album, the one that everything beforehand was leading to. In hindsight, it's also come to be seen as the end of Springsteen's peak era, with all of his first seven albums being more or less critically adored in the subsequent decades, and everything post Born In The U.S.A. subject to more debate. It's the pivot point: everything after it exists in relation to it. This is the case not only because of its commercial stature amongst Springsteen's catalog and pop music in general, but also because this is the album most representative of everything Springsteen was and is as an artist. With the benefit of thirty years to situate itself, Born In The U.S.A. feels like a centerpiece around which the rest of Springsteen's career revolves, the one perfect distillation of all the stories he wanted to tell and all the voices he wanted to tell them in.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Having grown up in a depressed nowhere-ish town in Pennsylvania forever occupied with dreams and visions of taking off, of moving to the city, a lot of Springsteen's early music is made specifically for people like me. Born To Run sounded like it lead to another world, not just because it was so intricate, so intent upon crafting escape through imbuing music with legend so thoroughly, but also because its own visions of escape felt like they belonged so thoroughly to a bygone time. They were unretrievable; if anybody ever really got in their car and just drove away to a new start, they didn't do it now. Of course, most of the people in his songs never quite make it out of that town they start out in, anyway. The bar scenes of "Glory Days" or the father-son cycle of "My Hometown" might fly in the face of this notion, but in recent years I've begun to think of Born In The U.S.A. as the Bruce album for those of us who came from such places, actually did make it to the destination at the other end, and didn't know exactly what was supposed to have changed once we got there.

Springsteen has two albums that begin with the word "born": Born To Run and Born In The U.S.A. People will argue about where these fall in the canon (in my mind, there's no way both of them aren't in the top 3), but there's no getting around that these are his most iconic albums. The first was the last gasp of his romantic period, as operatic and grandiose as he'd ever let himself be ever again. Born To Run is the one that minted him as a star, Born In The U.S.A. of course the one that took it much further. They feel like bookends, his first two albums a prologue to Born To Run's Point A, the subsequent three albums the middle chapters on the way to Born In The U.S.A.'s Point B. With those seven albums, you get the whole arc of Springsteen's first story. There's a reason he followed Born In The U.S.A. with Tunnel Of Love, a departure stylistically and conceptually, and there's a reason he never quite got his muse back after that until he had post-9/11 America to grapple with. Those first seven albums should rank as one of the Great American Novels. They flit between grand dreams of escapism and classic Americana iconography and far more grim, sparse portraits of real, non-archetypal characters struggling in a spiritual and economic wasteland in a post-Vietnam America. Born In The U.S.A. holds all that within it, and seeks some sort of resolution, offers some hope. It's the one you carry with you on the other end of trip.

One would imagine it's no coincidence -- and if it is, it's still illustrative -- that the word "run" also appears in the lyrics to "Born In The U.S.A." In "Born To Run," the famous line had been "Tramps like us, baby we were born to run." It was a desperate, last-bet kind of romanticism that ran through Born To Run, but it was still one final shot at throwing your arms around the highway and all the promises you wish you still totally believed it offered. On Born In The U.S.A., any sense of romanticism comes in yearning and nostalgia, simple pop forms rather than intricately crafted catharses. When he sings of running in "Born In The U.S.A.," there's no more glimpse of pulling out of town -- it's "Nowhere to run, ain't got nowhere to go." It's the lack of options, the lack of a perceived future, that drives this song's protagonist to Vietnam; it's his return from Vietnam that presents him with a heightened sense of that same lack. It's preceded by the line "Ten years burning down the road." Born In The U.S.A. came out just shy of ten years after Born To Run. This is the album where Born To Run ends, finally, all that came in between steps along that journey. While "Born In The U.S.A." may start it off despairingly, by "My Hometown" we're making peace with where we came from and who we are. There's an arc to this album specifically that puts to rest so many of the issues of the preceding six albums.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Despite all I've said here about the circumstances of this album and how it's been perceived, lately Born In The U.S.A. has transcended context for me. When I leave my apartment in New York on a rainy day, it seems like the right album to put on. When I visit home, in Pennsylvania, and I'm driving under grey skies on a five degree day in January, it seems like the right album to put on. When I'm walking home late at night on a balmy summer night, there's no way that I'm not putting on "Dancing In The Dark" before I'm done. Usually, when a piece of art becomes voluminous or malleable enough to mean everything, it winds up not meaning much at all. Born In The U.S.A. is an exception, a record whose myth just feels more massive and inviting even now. Or, maybe, that's just what this kind of pop music is supposed to be: a different version of everything to anybody who listens to it.

Even when you live in a place like New York, that urge can develop, that unquenchable recurring American thing of wanting to escape where you are. No matter where it is, the answers are elsewhere. Of course, that's the kind of thinking Springsteen already tried, and he knew it didn't hold up. But he still wanted to believe it, even on Born In The U.S.A., where he's pretty much deconstructing the notion. It's in our DNA, that desire -- something about the expanse of America, the big abstract promises of this country, instills a hunger. There's always that possibility to blow everything up and start again in a new town. And in the 21st century, that's only gotten stronger, even if it seems like a particularly American Century notion that should be outmoded. We might be savvy enough to know that our existence won't look like the dreams earlier Springsteen songs sketched out, the dreams so many of his later protagonists suffered having lost. But the flipside of that savviness, I'd argue, is that we also live with a perpetual sense of "Is that all?" We have, in a sense, everything at our fingertips, but it's never enough. It begins to feel like nothing.

So every now and then, it helps to put on Born In The U.S.A., because of that fact that it's the one that represents the end of the road of all he'd written up until that point: a mature reckoning with all the mythology he'd been raised on, a grounding of it in the daily realities of people's lives, and a glimmer of wistfulness and belief that it's still possible to grasp at it all. There are days recently where I find it to be the most rewarding, most essential, most immortal Bruce Springsteen record. Anytime I put it on, for 47 minutes there's that intangible sense rising again -- not the hunger, but the response to it. The point where you had the belief, lost it for a time, and are old enough to come back around to it tentatively, just taking little doses of it amongst your daily, physical realities. It might ring out in desperation sometimes, but thirty years on it feels more like a tinge of something new, and a promise to carry on: "There's something happening somewhere." Sometimes, I just know that there is.