For a band that has sold more than 40 million albums worldwide, whose streak of consecutive gold and platinum records is topped only by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, trying to nail down the exact reason why Canadian trio Rush is so adored by so many is never easy. Reviled by critics -- or worse, completely ignored -- for a good portion of their career, Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson, and Neil Peart have defied odds time and again, the music showing a remarkable amorphous quality, changing with the times yet never pandering, retaining an astounding level of popularity to this day.

Although the band's groundbreaking combination of heavy metal and progressive rock was what made it famous in the first place, appealing greatly to the teenaged hesher crowd in the '70s while the critical elite scoffed, to call Rush a "progressive power trio" today is like calling Bob Dylan a protest singer. There's so much more to the band than that -- more musical and thematic variety than many are willing to acknowledge. Rush has dabbled in new wave, electronic music, pop, reggae, and world music, the wide array of instruments all three employ redefining what a rock trio could accomplish onstage. The technical skill of the three musicians is staggering: Lifeson's expressive, versatile guitar playing, Lee's impressive dexterity on bass and keyboards -- often at the same time -- and not the least of which, the inimitable Mr. Peart, the only rock drummer alive for whom everyone remains in their seat when it's time for his drum solo. Despite the musical chops on display, though, songcraft always comes first. Unlike so many progressive metal bands today, Rush has always known that even prog rock is pointless if it doesn't have a hook. Not many bands can write an instrumental that compels a crowd of 40,000 people to sing along to it, but Rush have written several.

Additionally, Rush have always been incredibly grounded. Self-indulgent but always self-aware, a sense of levity has always served as a welcome undercurrent in the band's work, whether making fun of their friends in KISS in a song in 1975, subtitling an instrumental "an exercise in self-indulgence," the visual puns of the Moving Pictures cover art, or the band's increasingly absurd and hilarious short films that precede each concert. The music can seem arch at times, but Rush always remember to laugh a little. It's serious, but more importantly, it's fun. It's supposed to be.

Before Iron Maiden, Metallica, and Slayer attracted global popularity with little to no help from radio or mainstream music press, Rush set the standard. Not once did the band rely on music tastemakers to spread the word. Although the band received a couple mildly positive reviews from Rolling Stone, they were never given a proper feature in the 1970s or '80s. Spin was always too hip for Rush. Goodness knows they never landed on the Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop critics' poll.

Rush might be what Lee whimsically describes as "the world's biggest cult band," but never has Rush ever been cool. It's unapologetically nerdy music, but it's also welcoming. Cool people need not apply, and there's something immensely appealing about that. It's for everyone. If you go to a Rush concert today, you'll see one of the more convivial environments you'll ever witness at a rock show. Everyone's on the same level, three, maybe even four generations represented. A lot more women than you'd expect, shattering the myth that Rush is a boys' club. During Peart's solos you'll see fathers hoist their awestruck children onto their shoulders to witness the mastery at hand. And when "Tom Sawyer" climaxes, people, no matter how hip they are, no matter what age, will be compelled to air-drum along to Peart's legendary fills.

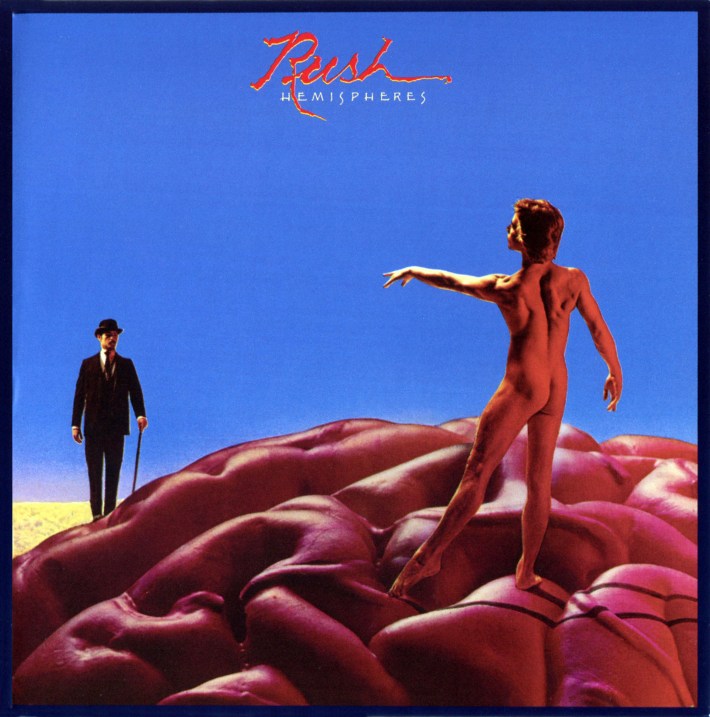

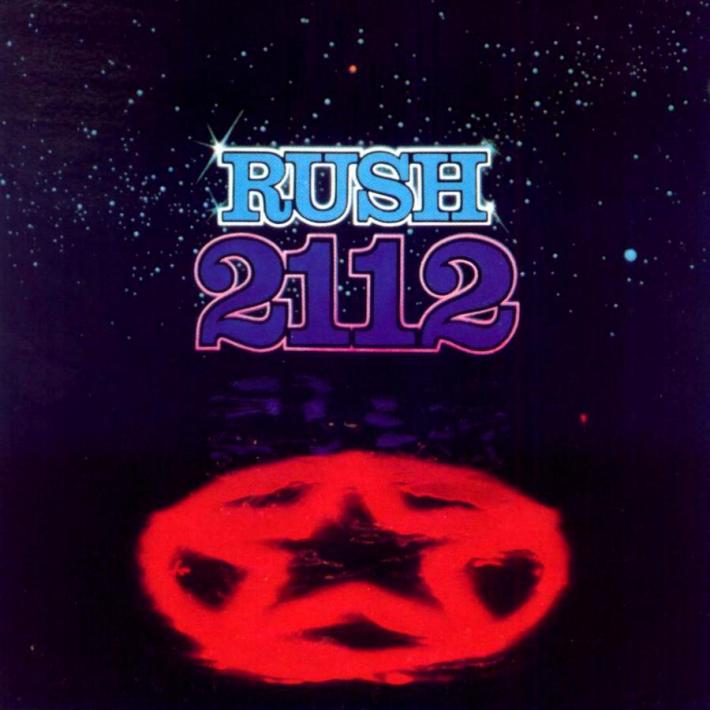

Whether your favorite album is 2112, Hemispheres, Moving Pictures, Grace Under Pressure, or, heaven help you, Roll The Bones, the unifying factor with all of those records is that Rush have always been uncompromising. When their third album flopped, Rush had a choice in 1976: to acquiesce to the demands of the record label, or to defiantly do their own thing. They chose the latter, achieved worldwide fame soon after, and were never again told what to do. Rush is the living embodiment of integrity in rock music, and it's for that simple reason that we celebrate the Canadian legends' vast, rich discography.

As a Rush fan since 1984, I have my own personal favorites -- your favorite Rush album is often your first Rush album, so for me it's Grace Under Pressure -- but I took it upon myself to dispose of any trace of fandom and examine all 19 albums (and one mini-album) with as objective a critical ear as possible. Some rankings might be cause for debate, but that's why I've written this piece: for folks to discuss, debate, and above all, celebrate this band's wonderful, enthralling, and perpetually endearing body of work.

This July marks the 40th year that Dirk, Lerxst, and the Professor have been together. Boys, we wish you well, and thank you for the music. (Also, feel free to follow me on Twitter at @basementgalaxy, where the Rush talk never ceases.)

Coda:

Rush enthusiasts are nothing if not a little bit obsessive, yours truly included, and no discussion of the band's discography would be complete without the inevitable comment, "But what about the live albums?" So just to be thorough, here's a quick ranking of Rush's live albums, from best to, erm, least worst.

01. All The World's A Stage (1976)

02. Rush In Rio (2003)

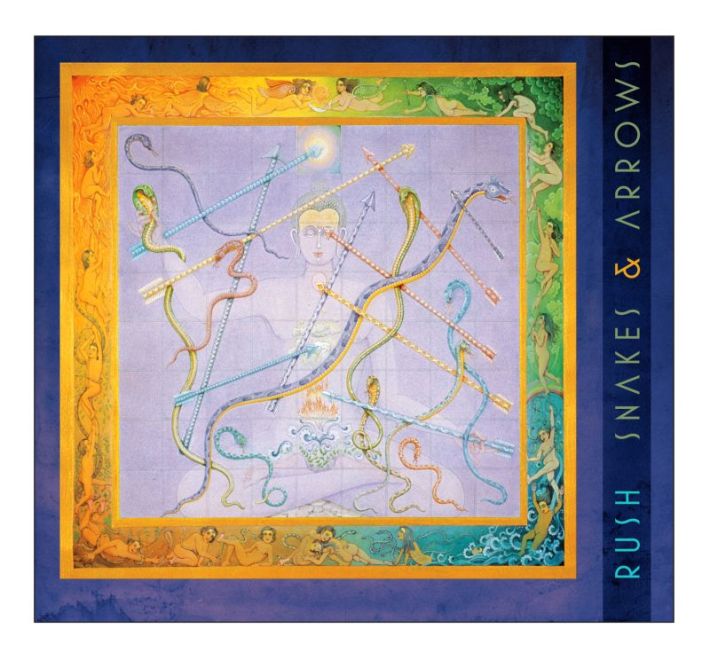

03. Snakes & Arrows Live (2008)

04. A Show Of Hands (1989)

05. Exit…Stage Left (1981)

06. Clockwork Angels Tour (2013)

07. Grace Under Pressure Tour (2005)

08. Different Stages (1998)

09. R30: 30th Anniversary World Tour (2005)

10. Time Machine 2011: Live In Cleveland (2011)

Rush has displayed incredible consistency over the course of the last 40 years, but the band is not above reproach. When it comes to the three albums in the discography that can be legitimately called failures, each misfired for completely different reasons. 1975's Caress Of Steel was a misguided attempt to expand the band's broadening progressive rock direction, and 1991's Roll The Bones was lost in a high-gloss rabbit hole of muddled, middling album oriented rock. Test For Echo, on the other hand, was much less excusable: a completely uninspired effort by a band that had been around enough to know better.

Even the mediocre Rush albums have a handful of great, memorable songs. Caress Of Steel has "Bastille Day," Roll The Bones has "Dreamline," "Bravado," and "Ghost Of A Chance." Test For Echo has nothing. It's actually extraordinary how Lee, Lifeson, and Peart push all the buttons and seem like Rush, a comfortable air of familiarity permeating the entire record, yet it is so empty, totally devoid of hooks. Everyone just goes through the motions. As a music fan, that's one of the most depressing things to hear; you try hard to make some sort of connection with the music, but it is so uninspired, so forgettable, that it all becomes a futile exercise.

"Test For Echo," "Driven," and "Half The World" try hard to continue the momentum that the very strong return to form Counterparts created three years earlier, but the melodies are hopelessly dour, lacking the vibrancy of the previous album. "Resist" is a desperate attempt to follow up successful ballads like "The Pass" and "Nobody's Hero," but it is awash in forced emotion and schmaltz. Peart's thoughtful lyrics are wasted as each subsequent song fails to deliver, but even he goes too far on a pair of cringe-inducing late-album duds. Nothing dates songs worse than writing lyrics about technology, and "Virtuality," which might have sounded contemporary nearly two decades ago, now feels as antiquated as a 28.8 dial-up modem ("Net boy, net girl/ Send your impulse 'round the world/ Put your message in a modem/ And throw it in the Cyber Sea"). Meanwhile "Dog Years," which bears a strange resemblance to late-'80s Hüsker Dü -- go figure -- is as clunky a metaphor as Peart has ever used. "A year is really more like seven/ And all too soon a canine/ Will be chasing cars in doggie heaven." Come on, Professor.

This being a Rush album, Test For Echo nevertheless peaked at number five in America, and the tour in support of the record was a successful one, which featured a performance of "2112" in its entirety. As mediocre as the album was, nobody could have expected Rush's show in Ottawa on July 4, 1997 would be its last show for a very long time, as personal tragedy would put the band's future in serious jeopardy.

Rush has displayed incredible consistency over the course of the last 40 years, but the band is not above reproach. When it comes to the three albums in the discography that can be legitimately called failures, each misfired for completely different reasons. 1975's Caress Of Steel was a misguided attempt to expand the band's broadening progressive rock direction, and 1991's Roll The Bones was lost in a high-gloss rabbit hole of muddled, middling album oriented rock. Test For Echo, on the other hand, was much less excusable: a completely uninspired effort by a band that had been around enough to know better.

Even the mediocre Rush albums have a handful of great, memorable songs. Caress Of Steel has "Bastille Day," Roll The Bones has "Dreamline," "Bravado," and "Ghost Of A Chance." Test For Echo has nothing. It's actually extraordinary how Lee, Lifeson, and Peart push all the buttons and seem like Rush, a comfortable air of familiarity permeating the entire record, yet it is so empty, totally devoid of hooks. Everyone just goes through the motions. As a music fan, that's one of the most depressing things to hear; you try hard to make some sort of connection with the music, but it is so uninspired, so forgettable, that it all becomes a futile exercise.

"Test For Echo," "Driven," and "Half The World" try hard to continue the momentum that the very strong return to form Counterparts created three years earlier, but the melodies are hopelessly dour, lacking the vibrancy of the previous album. "Resist" is a desperate attempt to follow up successful ballads like "The Pass" and "Nobody's Hero," but it is awash in forced emotion and schmaltz. Peart's thoughtful lyrics are wasted as each subsequent song fails to deliver, but even he goes too far on a pair of cringe-inducing late-album duds. Nothing dates songs worse than writing lyrics about technology, and "Virtuality," which might have sounded contemporary nearly two decades ago, now feels as antiquated as a 28.8 dial-up modem ("Net boy, net girl/ Send your impulse 'round the world/ Put your message in a modem/ And throw it in the Cyber Sea"). Meanwhile "Dog Years," which bears a strange resemblance to late-'80s Hüsker Dü -- go figure -- is as clunky a metaphor as Peart has ever used. "A year is really more like seven/ And all too soon a canine/ Will be chasing cars in doggie heaven." Come on, Professor.

This being a Rush album, Test For Echo nevertheless peaked at number five in America, and the tour in support of the record was a successful one, which featured a performance of "2112" in its entirety. As mediocre as the album was, nobody could have expected Rush's show in Ottawa on July 4, 1997 would be its last show for a very long time, as personal tragedy would put the band's future in serious jeopardy.

By mid-1975 all signs pointed toward a major commercial breakthrough for Rush. Fly By Night had turned into a minor hit, landing the band some plum tour slots, opening for KISS, Aerosmith, and Blue Öyster Cult. As was the custom in the music industry at the time, the iron had to be struck while it was still hot. The boys had some serious momentum happening, so why not have them crank out another album for a late-year release? They were young and full of ambition, and to make things even better, were given three weeks to record, which, compared to the previous two albums, was a luxury. That crucial, successful third album seemed like an inevitability. How could they mess that up?

Well, they did. Maybe a sign that Caress Of Steel was doomed was how the intended silver cover art was mistakenly rendered a murky copper color by printers instead. Either way, Rush's third album was a brutal misfire, both artistically and commercially. It starts off in very strong fashion with the boisterous, anthemic "Bastille Day," a spot-on encapsulation of the way Rush continued to perfect Zeppelin-sized riffs, progressive rock experimentation, and storytelling. However, it's all downhill from there. "I Think I'm Going Bald" is a lark, a funny poke at Max Webster frontman and friend of the band Kim Mitchell -- as well as a piss-take on KISS's "Goin' Blind' -- but is nothing more than a toss-off, better suited as a B-side. "Lakeside Park" is clearly "Fly By Night" Part Two, with Neil Peart waxing nostalgic for his St. Catharines home atop a pastoral-sounding arrangement, but lacking the grace, charm, and hooks of the single it tries so hard to mimic.

Caress Of Steel's most egregious mistake is cramming in two gigantic epics, neither of which succeeds at all. The 12 and a half-minute "The Necromancer" is bogged down by a horribly complicated, sleepy narration by Peart, whose voice is pitch-shifted to a comically low register. Only the final third of the song, a section called "Return Of The Prince," is worth noting for its shameless rip-off of the Velvet Underground's "Sweet Jane." It's with the 20-minute "The Fountain Of Lamneth," though, where Peart, Lee, and Lifeson bite off more than they can chew. They have the right idea -- the wicked signature riff of "In The Valley" is reprised wonderfully in the closing movement "The Fountain" -- but the song quickly becomes muddled with song fragments that are awkwardly stitched together. It's a harsh lesson every progressive rock and metal band goes through at one point: you can be as experimental, as technically ambitious as you want, but even prog has to be catchy, and these two songs were unmitigated failures.

Needless to say, audiences were baffled by what they heard on Caress of Steel, and consequently sales plummeted. Things got so dire for the band that its tour in support of the record was jokingly dubbed the "Down The Tubes Tour," and Mercury Records in the United States was less than impressed, pushing the band to put out another proper "hit" single rather than all this self-indulgence. Rush's true turning point had arrived: either succumb to the demands of the label, or take a mulligan on Caress Of Steel and record the prog rock magnum opus they knew they had in them. The band opted for the latter option, and just six months later would have an all-time classic album under its belt.

By mid-1975 all signs pointed toward a major commercial breakthrough for Rush. Fly By Night had turned into a minor hit, landing the band some plum tour slots, opening for KISS, Aerosmith, and Blue Öyster Cult. As was the custom in the music industry at the time, the iron had to be struck while it was still hot. The boys had some serious momentum happening, so why not have them crank out another album for a late-year release? They were young and full of ambition, and to make things even better, were given three weeks to record, which, compared to the previous two albums, was a luxury. That crucial, successful third album seemed like an inevitability. How could they mess that up?

Well, they did. Maybe a sign that Caress Of Steel was doomed was how the intended silver cover art was mistakenly rendered a murky copper color by printers instead. Either way, Rush's third album was a brutal misfire, both artistically and commercially. It starts off in very strong fashion with the boisterous, anthemic "Bastille Day," a spot-on encapsulation of the way Rush continued to perfect Zeppelin-sized riffs, progressive rock experimentation, and storytelling. However, it's all downhill from there. "I Think I'm Going Bald" is a lark, a funny poke at Max Webster frontman and friend of the band Kim Mitchell -- as well as a piss-take on KISS's "Goin' Blind' -- but is nothing more than a toss-off, better suited as a B-side. "Lakeside Park" is clearly "Fly By Night" Part Two, with Neil Peart waxing nostalgic for his St. Catharines home atop a pastoral-sounding arrangement, but lacking the grace, charm, and hooks of the single it tries so hard to mimic.

Caress Of Steel's most egregious mistake is cramming in two gigantic epics, neither of which succeeds at all. The 12 and a half-minute "The Necromancer" is bogged down by a horribly complicated, sleepy narration by Peart, whose voice is pitch-shifted to a comically low register. Only the final third of the song, a section called "Return Of The Prince," is worth noting for its shameless rip-off of the Velvet Underground's "Sweet Jane." It's with the 20-minute "The Fountain Of Lamneth," though, where Peart, Lee, and Lifeson bite off more than they can chew. They have the right idea -- the wicked signature riff of "In The Valley" is reprised wonderfully in the closing movement "The Fountain" -- but the song quickly becomes muddled with song fragments that are awkwardly stitched together. It's a harsh lesson every progressive rock and metal band goes through at one point: you can be as experimental, as technically ambitious as you want, but even prog has to be catchy, and these two songs were unmitigated failures.

Needless to say, audiences were baffled by what they heard on Caress of Steel, and consequently sales plummeted. Things got so dire for the band that its tour in support of the record was jokingly dubbed the "Down The Tubes Tour," and Mercury Records in the United States was less than impressed, pushing the band to put out another proper "hit" single rather than all this self-indulgence. Rush's true turning point had arrived: either succumb to the demands of the label, or take a mulligan on Caress Of Steel and record the prog rock magnum opus they knew they had in them. The band opted for the latter option, and just six months later would have an all-time classic album under its belt.

Why did it happen? It shouldn't have happened.

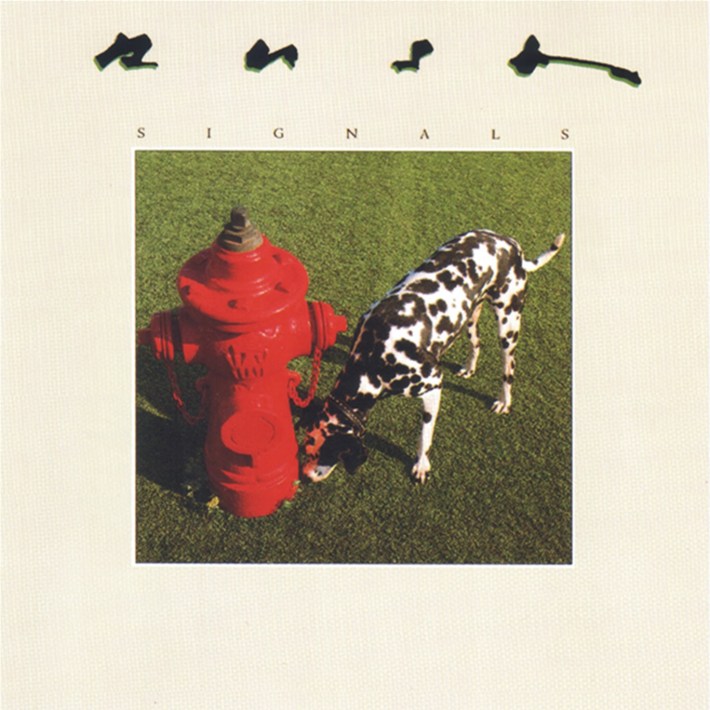

But Roll The Bones did indeed happen, and it did startlingly good business, becoming Rush's biggest-selling album in America since Signals. Although it was wonderful to see Rush in the public consciousness in America more than usual, as mainstream rock music enjoyed its last days of fun before the miserable post-grunge wave washed it away, it's the one Rush album that has gone on to age the worst.

Like on Presto two years earlier, Roll The Bones saw Lee, Lifeson, and Peart recording with producer Rupert Hine, who had taken the high-gloss style the band had created with Peter Collins and molded it in a more guitar-oriented style that made it a little more palatable for classic rock fans. Interestingly, though, unlike Presto's wildly bipolar range from inspired to abysmal, aside from three legitimately good moments, Roll The Bones settles into a rut of complacent mediocrity.

To this day I don't understand why "Dreamline" became the band's biggest Stateside radio hit in years, but when it was released in the fall of 1991, the upbeat track swiftly ascended to the top of the mainstream rock chart. Granted, it is a very good little song, a propulsive road movie of a rocker, Peart's restless lyrics ("We're only at home when we're on the run") going well with the simple yet ominous driving riff that looms over the song like darkening clouds on the horizon. "Bravado" is structurally every bit the equal of "The Pass" -- so much so that both songs were played on alternate nights on Rush's 2012-'13 tour -- and it very nearly succeeds just as well, thanks to Lifeson's soulful guitar work and Peart's fluid drumming. "Ghost Of A Chance," meanwhile, might be a total lightweight compared to classic Rush rock tracks, but its robust groove is countered by a lovely, introspective chorus. All three songs would go on to be well liked by the band and its audience, with "Dreamline" being a longtime concert staple.

The rest of Roll The Bones, unfortunately, is a portrait of Rush sounding utterly lost. "Face Up," "The Big Wheel," "Neurotica," and "You Bet Your Life" are tepid, severely lacking something to ground them, whether guitars or keyboards. Instead is a milquetoast, sleek combination of the two, either afraid or unwilling to go in one particular direction. "Heresy" is as inexcusable as the similarly Midnight Oil-aping "Scars" was on Presto.

And the title track. Oh, the title track. "Roll The Bones" already flirts with disaster with its horn synth stabs, which already sounded passé in 1991, but the song will forever live in infamy for the mid-song rap, performed by a pitch-shifted Lee and cloyingly written by Peart. It's like a dad walking in on a teen basement party and rapping along to "Going Back To Cali" or "Fight The Power." He's not trying to lampoon the genre, he's just trying to come across as hip, and it only feels awkward and kind of sad:

"Jack, relax/ Get busy with the facts/ No zodiacs or almanacs/ No maniacs in polyester slacks/ Just the facts/ Gonna kick some gluteus max/ It's a parallax, you dig?"

Um…yeah. I, erm, dig. Please don't do that anymore.

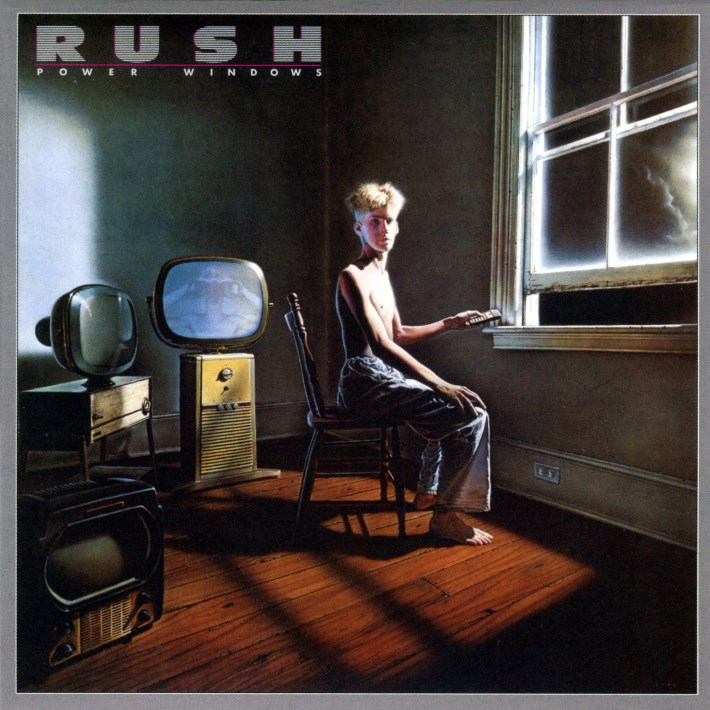

Roll The Bones did monstrously in America, returning the band to the platinum echelon for the first time since 1985's Power Windows, but like every other band from the 1970s and 1980s, Rush would have to adjust with the most dramatic sea change in rock history thanks to a host of slovenly musicians from Seattle. Its dabbling in pop had pulled the band down a rabbit hole, rendering the brand out of date, and a serious adjustment would be needed if the guys had any hope of clawing out with integrity intact.

Why did it happen? It shouldn't have happened.

But Roll The Bones did indeed happen, and it did startlingly good business, becoming Rush's biggest-selling album in America since Signals. Although it was wonderful to see Rush in the public consciousness in America more than usual, as mainstream rock music enjoyed its last days of fun before the miserable post-grunge wave washed it away, it's the one Rush album that has gone on to age the worst.

Like on Presto two years earlier, Roll The Bones saw Lee, Lifeson, and Peart recording with producer Rupert Hine, who had taken the high-gloss style the band had created with Peter Collins and molded it in a more guitar-oriented style that made it a little more palatable for classic rock fans. Interestingly, though, unlike Presto's wildly bipolar range from inspired to abysmal, aside from three legitimately good moments, Roll The Bones settles into a rut of complacent mediocrity.

To this day I don't understand why "Dreamline" became the band's biggest Stateside radio hit in years, but when it was released in the fall of 1991, the upbeat track swiftly ascended to the top of the mainstream rock chart. Granted, it is a very good little song, a propulsive road movie of a rocker, Peart's restless lyrics ("We're only at home when we're on the run") going well with the simple yet ominous driving riff that looms over the song like darkening clouds on the horizon. "Bravado" is structurally every bit the equal of "The Pass" -- so much so that both songs were played on alternate nights on Rush's 2012-'13 tour -- and it very nearly succeeds just as well, thanks to Lifeson's soulful guitar work and Peart's fluid drumming. "Ghost Of A Chance," meanwhile, might be a total lightweight compared to classic Rush rock tracks, but its robust groove is countered by a lovely, introspective chorus. All three songs would go on to be well liked by the band and its audience, with "Dreamline" being a longtime concert staple.

The rest of Roll The Bones, unfortunately, is a portrait of Rush sounding utterly lost. "Face Up," "The Big Wheel," "Neurotica," and "You Bet Your Life" are tepid, severely lacking something to ground them, whether guitars or keyboards. Instead is a milquetoast, sleek combination of the two, either afraid or unwilling to go in one particular direction. "Heresy" is as inexcusable as the similarly Midnight Oil-aping "Scars" was on Presto.

And the title track. Oh, the title track. "Roll The Bones" already flirts with disaster with its horn synth stabs, which already sounded passé in 1991, but the song will forever live in infamy for the mid-song rap, performed by a pitch-shifted Lee and cloyingly written by Peart. It's like a dad walking in on a teen basement party and rapping along to "Going Back To Cali" or "Fight The Power." He's not trying to lampoon the genre, he's just trying to come across as hip, and it only feels awkward and kind of sad:

"Jack, relax/ Get busy with the facts/ No zodiacs or almanacs/ No maniacs in polyester slacks/ Just the facts/ Gonna kick some gluteus max/ It's a parallax, you dig?"

Um…yeah. I, erm, dig. Please don't do that anymore.

Roll The Bones did monstrously in America, returning the band to the platinum echelon for the first time since 1985's Power Windows, but like every other band from the 1970s and 1980s, Rush would have to adjust with the most dramatic sea change in rock history thanks to a host of slovenly musicians from Seattle. Its dabbling in pop had pulled the band down a rabbit hole, rendering the brand out of date, and a serious adjustment would be needed if the guys had any hope of clawing out with integrity intact.

Once Rush returned to action in 2002, demand to see the band perform was at an all time high, and Lee, Lifeson, and Peart spent a good part of the next decade touring. Long, two-part "evening with" live sets were accentuated by stage presentations that pulled out all the stops, and the band took the opportunity to showcase its wry sense of humor even more with self-effacing video clips and Lee's new penchant for hilarious props that replaced his retired bass cabinets -- including dryers, chicken roasters, and vending machines. While Rush was never devoid of charm, their post-2002 run of concerts made them an even more likeable bunch than ever.

In the wake of the world tour in support of Vapor Trails, the band commenced another tour in 2004 to commemorate its 30th anniversary. In order to have a product to flog, the idea arose to record a short covers album featuring Rush-ified versions of classic rock songs from the band's teen years, and the resulting mini-album Feedback turned out to be a very pleasant surprise.

Covers albums are commonplace these days, especially in hard rock and metal, to the point where it's impossible to not view them with skepticism, but Feedback is a rare successful exception. Not only are these eight renditions performed very well, showing longtime fans how each song influenced the band in certain ways, but they show a side of Rush people hadn't heard before, one that's loose, groovy, and ebullient. "Summertime Blues" brilliantly combines Blue Cheer's raucous version and the Who's intense cover of the Eddie Cochran tune. The Yardbirds' "Shapes Of Things" and "Heart Full Of Soul" showcase a psychedelic side to the band, while Buffalo Springfield's "For What It's Worth" and "Mr. Soul" are given considerably darker treatments than the originals. While the Who's "The Seeker" capably replicates the original's ferocious groove, Arthur Lee's "Seven And Seven Is" is more intense, performed with tremendous energy and joy, and Cream's "Crossroads" is a full-on rampager, proof that Rush could evoke the blues as well as any rock band.

In the end what Feedback does best is completely strip away any lingering façade the band might have had that linked it to arch, complex, pretentious progressive rock. They're not aging 50-something geezers on this record, but a trio of youngsters banging away on their instruments in their garage. Sometimes it's best for even the most established and famous rock bands to get back to their roots, and Feedback felt like a valuable, rejuvenating exercise for everyone involved, paving the way for a pair of outstanding late-career albums that would follow.

Once Rush returned to action in 2002, demand to see the band perform was at an all time high, and Lee, Lifeson, and Peart spent a good part of the next decade touring. Long, two-part "evening with" live sets were accentuated by stage presentations that pulled out all the stops, and the band took the opportunity to showcase its wry sense of humor even more with self-effacing video clips and Lee's new penchant for hilarious props that replaced his retired bass cabinets -- including dryers, chicken roasters, and vending machines. While Rush was never devoid of charm, their post-2002 run of concerts made them an even more likeable bunch than ever.

In the wake of the world tour in support of Vapor Trails, the band commenced another tour in 2004 to commemorate its 30th anniversary. In order to have a product to flog, the idea arose to record a short covers album featuring Rush-ified versions of classic rock songs from the band's teen years, and the resulting mini-album Feedback turned out to be a very pleasant surprise.

Covers albums are commonplace these days, especially in hard rock and metal, to the point where it's impossible to not view them with skepticism, but Feedback is a rare successful exception. Not only are these eight renditions performed very well, showing longtime fans how each song influenced the band in certain ways, but they show a side of Rush people hadn't heard before, one that's loose, groovy, and ebullient. "Summertime Blues" brilliantly combines Blue Cheer's raucous version and the Who's intense cover of the Eddie Cochran tune. The Yardbirds' "Shapes Of Things" and "Heart Full Of Soul" showcase a psychedelic side to the band, while Buffalo Springfield's "For What It's Worth" and "Mr. Soul" are given considerably darker treatments than the originals. While the Who's "The Seeker" capably replicates the original's ferocious groove, Arthur Lee's "Seven And Seven Is" is more intense, performed with tremendous energy and joy, and Cream's "Crossroads" is a full-on rampager, proof that Rush could evoke the blues as well as any rock band.

In the end what Feedback does best is completely strip away any lingering façade the band might have had that linked it to arch, complex, pretentious progressive rock. They're not aging 50-something geezers on this record, but a trio of youngsters banging away on their instruments in their garage. Sometimes it's best for even the most established and famous rock bands to get back to their roots, and Feedback felt like a valuable, rejuvenating exercise for everyone involved, paving the way for a pair of outstanding late-career albums that would follow.

In 1997 and 1998 Rush's comfortable, relatively peaceful world was rocked by unimaginable tragedy. Neil Peart's daughter Selena was killed in a highway accident on her way back to university on July 4, 1997, and if that wasn't awful enough, his wife Jackie died of cancer ten months later, inconsolable after the loss of her daughter. At Selena's funeral Peart told his bandmates to consider him retired, and after Jackie's death he set off on a colossal, 55,000 mile motorcycle journey that would result in his bestselling memoir Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road. As long as Peart was out, Rush was no longer a band; it was as simple as that. It would only continue if he decided to return, and it wouldn't be years until Lee and Lifeson got a definitive answer. In the meantime, the pair kept up appearances at public events, and Lee kept the creative juices flowing, putting out his solo debut My Favorite Headache in 2000.

In 2001, Peart started to let his mates know he was ready to try to make new music again, and so began the long, laborious, 14-month feeling-out process that would result in Vapor Trails. As Lifeson would tell writer Martin Popoff, "The expectations were different. It wasn't the same band anymore, and we weren't the same people -- not just because of what happened to Neil. We had all grown and matured a lot. When you get to your mid-40s, you definitely go through a change, and I think that's reflected in the sound."

It's interesting how all this was going on at the same time as a lost and creatively stifled Metallica was trying to find itself again in exactly the same way. Although one could easily draw parallels between Vapor Trails and St. Anger -- both are brutally stripped down, feature looser and grittier-sounding recordings, dabble in atonality, eschew guitar solos, were overlong, and were agonized over -- what sets Rush's effort apart is the undeniable chemistry between the three musicians, which miraculously remains intact throughout. It was a new Rush people were hearing, but that old familiarity was there as well, and although it was far from a rousing success, it was a very encouraging sign, with a handful of songs that are a pure joy.

It's absolutely fitting for this album to be kicked off by Peart, and "One Little Victory" opens like a house on fire, featuring his most energetic drumming since 2112. Lee and Lifeson hold up their end with a nasty heavy rock groove, the darkness of the riff melody reflecting Peart's lyrics, which aren't so much optimistic as doggedly determined to get through tough times. And indeed, that's the prevailing feeling of Vapor Trails: therapy through creativity. It might not all work, but it's a necessary step for the band to take. "Ceiling Unlimited" is one of the album's brighter moments, made all the more potent by the band's simplified approach, this being the first album since Caress Of Steel to not include keyboards. The mid-album trifecta of "Vapor Trail," "Secret Touch," and "Earthshine" is especially strong, highlighted by Lee's vocal performances, his mature singing adding texture to the material. The key track, however, is "Ghost Rider," the closest Peart comes to directly addressing his hardships ("Pack up all those phantoms/ Shoulder that invisible load"), forming the album's heart and soul.

Complicating things are the differing mixes of the album that now exist. The original 2002 version of the album, for all its sporadic strengths, is marred by an unfortunately muddy, overly loud mix that reduces everything to sloppy-sounding sludge. Much superior, though, is the 2013 reissue, which was given a complete overhaul by David Bottrill. Although it doesn't make the inferior songs on the record any better, it makes the entire album much more pleasant a listen, bolstered by a much clearer, richer sound than the original ever had. If you're going to buy Vapor Trails, make it the remix, and ignore the 2002 version.

Vapor Trails was an experiment, and a necessary one at that. If it wasn't for that record, the world wouldn't have witnessed Rush's post-millennial renaissance, from the triumphant Rush In Rio live album, to the band's successful 30th Anniversary tour, to the late-career high water marks Snakes & Arrows and Clockwork Angels. "The greatest act can be one little victory," Peart writes at one point. Vapor Trails was such a little victory, a difficult, wrenching, modestly triumphant statement that Rush was back.

In 1997 and 1998 Rush's comfortable, relatively peaceful world was rocked by unimaginable tragedy. Neil Peart's daughter Selena was killed in a highway accident on her way back to university on July 4, 1997, and if that wasn't awful enough, his wife Jackie died of cancer ten months later, inconsolable after the loss of her daughter. At Selena's funeral Peart told his bandmates to consider him retired, and after Jackie's death he set off on a colossal, 55,000 mile motorcycle journey that would result in his bestselling memoir Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road. As long as Peart was out, Rush was no longer a band; it was as simple as that. It would only continue if he decided to return, and it wouldn't be years until Lee and Lifeson got a definitive answer. In the meantime, the pair kept up appearances at public events, and Lee kept the creative juices flowing, putting out his solo debut My Favorite Headache in 2000.

In 2001, Peart started to let his mates know he was ready to try to make new music again, and so began the long, laborious, 14-month feeling-out process that would result in Vapor Trails. As Lifeson would tell writer Martin Popoff, "The expectations were different. It wasn't the same band anymore, and we weren't the same people -- not just because of what happened to Neil. We had all grown and matured a lot. When you get to your mid-40s, you definitely go through a change, and I think that's reflected in the sound."

It's interesting how all this was going on at the same time as a lost and creatively stifled Metallica was trying to find itself again in exactly the same way. Although one could easily draw parallels between Vapor Trails and St. Anger -- both are brutally stripped down, feature looser and grittier-sounding recordings, dabble in atonality, eschew guitar solos, were overlong, and were agonized over -- what sets Rush's effort apart is the undeniable chemistry between the three musicians, which miraculously remains intact throughout. It was a new Rush people were hearing, but that old familiarity was there as well, and although it was far from a rousing success, it was a very encouraging sign, with a handful of songs that are a pure joy.

It's absolutely fitting for this album to be kicked off by Peart, and "One Little Victory" opens like a house on fire, featuring his most energetic drumming since 2112. Lee and Lifeson hold up their end with a nasty heavy rock groove, the darkness of the riff melody reflecting Peart's lyrics, which aren't so much optimistic as doggedly determined to get through tough times. And indeed, that's the prevailing feeling of Vapor Trails: therapy through creativity. It might not all work, but it's a necessary step for the band to take. "Ceiling Unlimited" is one of the album's brighter moments, made all the more potent by the band's simplified approach, this being the first album since Caress Of Steel to not include keyboards. The mid-album trifecta of "Vapor Trail," "Secret Touch," and "Earthshine" is especially strong, highlighted by Lee's vocal performances, his mature singing adding texture to the material. The key track, however, is "Ghost Rider," the closest Peart comes to directly addressing his hardships ("Pack up all those phantoms/ Shoulder that invisible load"), forming the album's heart and soul.

Complicating things are the differing mixes of the album that now exist. The original 2002 version of the album, for all its sporadic strengths, is marred by an unfortunately muddy, overly loud mix that reduces everything to sloppy-sounding sludge. Much superior, though, is the 2013 reissue, which was given a complete overhaul by David Bottrill. Although it doesn't make the inferior songs on the record any better, it makes the entire album much more pleasant a listen, bolstered by a much clearer, richer sound than the original ever had. If you're going to buy Vapor Trails, make it the remix, and ignore the 2002 version.

Vapor Trails was an experiment, and a necessary one at that. If it wasn't for that record, the world wouldn't have witnessed Rush's post-millennial renaissance, from the triumphant Rush In Rio live album, to the band's successful 30th Anniversary tour, to the late-career high water marks Snakes & Arrows and Clockwork Angels. "The greatest act can be one little victory," Peart writes at one point. Vapor Trails was such a little victory, a difficult, wrenching, modestly triumphant statement that Rush was back.

Some bands hit the ground running on their debut albums, and others still sound like a work in progress. Nobody could predict what Rush would be capable of three years after its first full-length, let alone 40 years later, which in a way makes this innocuous little record all the more fascinating. Its legacy is nowhere near as towering as 2112 and Moving Pictures, and it's often a forgotten album in the Rush discography because it's the only record to not feature the classic lineup of Lee, Lifeson, and Peart. Yet for all its flaws, there's a charm to it, and given time -- it took decades for yours truly to warm to it -- it turns out to be a very likeable album.

By the time they headed into Toronto's Eastern Sound Studios in 1973, recording on the cheap after hours, Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson, and John Rutsey were veterans of the local rock scene, their many live performances honing their heavy rock sound, which translated very well on the self-titled album, which boasts the kind of robust tone that any aspiring heavy rock band hopes to pull off on its first effort. As confident as Rush is -- a good deal of credit goes to young studio whiz Terry Brown, who presided over the later recording sessions -- and as rare as it was for a Canadian band to explore the grittier, heavier side of rock at the time, it remains a very derivative album, the band shamelessly paying homage to Cream and Led Zeppelin, with Lifeson's riffs echoing Clapton and Page, Lee's chirpy voice coming across as a more polite, less cocksure Robert Plant. At its worst, which is nearly all of side one, its reliance on cliché is awkward: Lee's faux-American twang on "Take A Friend" is so obvious it's distracting, "Here Again" is tepid rather than slow-burning, while "Need Some Love" shows how badly the band needed a lyricist.

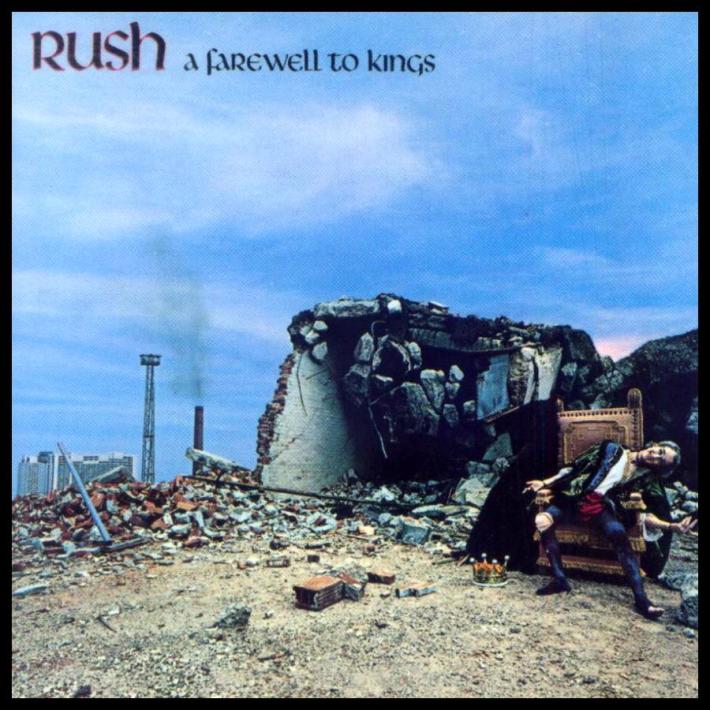

At its best, however, Rush is a scorching little rock 'n' roll record with surprising musical depth. With its marvelous, nimble fade-in intro by Lifeson, "Finding My Way" is a rambunctious way for Rush to introduce itself, its tone a lot more upbeat and optimistic despite the ominous, blues-derived lyrics. "What You're Doing" boasts a colossal groove, whose power would be amplified tenfold on the 1976 live album All The World's A Stage. Although hearing Lee sing, "Well-a hey now, baybeh," on "In The Mood" makes this writer smirk to this day, it remains a cute, quaint little garage rock tune. "Before And After," on the other hand, is an oft-overlooked highlight, bolstered by a gorgeous, pastoral first half that hints at musical territory Rush would explore on A Farewell To Kings three short years later.

The debut album's pinnacle is the final track, as "Working Man" swaggers in with a colossal heavy metal riff courtesy of Lifeson. Its lyrical simplicity ("I get up at seven, yeah/ And I go to work at nine/ I got no time for livin'/ Yes, I'm workin' all the time") is the one moment where it actually works. After all, blue-collar rock requires blue-collar lyrics, and it's rather fitting that the place where Rush got its first big break would happen to be working class Cleveland, who quickly embraced the track when it started spinning on WMMS radio. That popularity would in turn lead to the album's re-release in the United States, and better yet, loads of tour dates south of the border.

Unfortunately for Rutsey, the combination of the rock 'n' roll lifestyle and his diabetes contributed to his deteriorating health in early 1974, and with Rush's greatly increased commitments it quickly became clear he couldn't continue at that pace. The band needed a replacement, and they'd find one in the parts manager at a tractor dealer in St. Catharines, Ontario. Enter the Professor, and the rest, as they say, would be history.

Some bands hit the ground running on their debut albums, and others still sound like a work in progress. Nobody could predict what Rush would be capable of three years after its first full-length, let alone 40 years later, which in a way makes this innocuous little record all the more fascinating. Its legacy is nowhere near as towering as 2112 and Moving Pictures, and it's often a forgotten album in the Rush discography because it's the only record to not feature the classic lineup of Lee, Lifeson, and Peart. Yet for all its flaws, there's a charm to it, and given time -- it took decades for yours truly to warm to it -- it turns out to be a very likeable album.

By the time they headed into Toronto's Eastern Sound Studios in 1973, recording on the cheap after hours, Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson, and John Rutsey were veterans of the local rock scene, their many live performances honing their heavy rock sound, which translated very well on the self-titled album, which boasts the kind of robust tone that any aspiring heavy rock band hopes to pull off on its first effort. As confident as Rush is -- a good deal of credit goes to young studio whiz Terry Brown, who presided over the later recording sessions -- and as rare as it was for a Canadian band to explore the grittier, heavier side of rock at the time, it remains a very derivative album, the band shamelessly paying homage to Cream and Led Zeppelin, with Lifeson's riffs echoing Clapton and Page, Lee's chirpy voice coming across as a more polite, less cocksure Robert Plant. At its worst, which is nearly all of side one, its reliance on cliché is awkward: Lee's faux-American twang on "Take A Friend" is so obvious it's distracting, "Here Again" is tepid rather than slow-burning, while "Need Some Love" shows how badly the band needed a lyricist.

At its best, however, Rush is a scorching little rock 'n' roll record with surprising musical depth. With its marvelous, nimble fade-in intro by Lifeson, "Finding My Way" is a rambunctious way for Rush to introduce itself, its tone a lot more upbeat and optimistic despite the ominous, blues-derived lyrics. "What You're Doing" boasts a colossal groove, whose power would be amplified tenfold on the 1976 live album All The World's A Stage. Although hearing Lee sing, "Well-a hey now, baybeh," on "In The Mood" makes this writer smirk to this day, it remains a cute, quaint little garage rock tune. "Before And After," on the other hand, is an oft-overlooked highlight, bolstered by a gorgeous, pastoral first half that hints at musical territory Rush would explore on A Farewell To Kings three short years later.

The debut album's pinnacle is the final track, as "Working Man" swaggers in with a colossal heavy metal riff courtesy of Lifeson. Its lyrical simplicity ("I get up at seven, yeah/ And I go to work at nine/ I got no time for livin'/ Yes, I'm workin' all the time") is the one moment where it actually works. After all, blue-collar rock requires blue-collar lyrics, and it's rather fitting that the place where Rush got its first big break would happen to be working class Cleveland, who quickly embraced the track when it started spinning on WMMS radio. That popularity would in turn lead to the album's re-release in the United States, and better yet, loads of tour dates south of the border.

Unfortunately for Rutsey, the combination of the rock 'n' roll lifestyle and his diabetes contributed to his deteriorating health in early 1974, and with Rush's greatly increased commitments it quickly became clear he couldn't continue at that pace. The band needed a replacement, and they'd find one in the parts manager at a tractor dealer in St. Catharines, Ontario. Enter the Professor, and the rest, as they say, would be history.

When Rush's 13th album came out in late 1989, much was made about the band's purported return to the classic power trio hard rock of the early days. After a near decade of keyboard-centered forays into new wave and pop, this was Lee, Lifeson, and Peart's glorious return to rock, or as the press releases and interviews would lead folks to believe. And indeed, the band sounded a lot more robust on the lead-off single "Show Don't Tell" than they had in many years, the song kicking off with a quirky little groove that sounded lively and fun, and for many fans it was a joy to hear a new song that just had Dirk, Lerxt, and the Professor on bass, guitar, and drums. However, that brief little snippet, hyped as it was, was more of a red herring than anything else, as Presto would turn out to be yet another continuation of Rush's great pop experiment.

Replacing Peter Collins as producer was Rupert Hine, another British producer with a very strong pop/new wave background, having worked on albums by The Fixx, Howard Jones, and Tina Turner. Ironically, it would be Hine who would ease Rush out from under all the synths, resulting in an album that would make the arrangements more rock-oriented while still maintaining the strong pop sensibility of the band's musical direction at the time. However, what makes Presto such an anomaly in the band's discography is that despite bringing that traditional rock element back, it remains an oddly twee album.

Twee, but at its best, endearingly so. And the album does get off to a very strong start with four excellent tracks. "Show Don't Tell" is a prime example of Rush's skill at creating sly little prog rock suites in the pop milieu, balancing heavy rock, acoustic-tinged verses, and anthemic choruses. In lesser hands it would feel incongruous, but the way the band builds to the surprisingly graceful bridge -- with keyboards by Lee that enhance rather than overwhelm -- is masterful. "Chain Lightning" is much more conventional, perhaps a little beneath Rush, but they make it work, thanks to an affable little chorus accentuated by thin-sounding guitars by Lifeson that are so late-'80s they practically scream "Stephen Street." Equally rote is "War Paint," but the song offers a very good balance of pulsating rock and shimmering pop, culminating in a pleasing climactic chorus in its final minute. The real ace, however, is the majestic "The Pass." Prior to that song Rush's attempts at balladry always felt forced, but "The Pass" exudes grace, Peart eloquently musing about teen suicide ("Raging at unreachable glory/ Straining at invisible chains") and Lee turning in one of the best vocal performances of his career. It's a song the band remains immensely proud of -- Peart admits he gets choked up every time he plays it -- and one it still performs to this day.

After such an assured start, Presto quickly takes a turn for the worse. Featuring African-inspired rhythms by Peart and very ill-advised bass composed on sequencer, "Scars" goes awry almost instantly, the sound of a band more preoccupied with sounding like Midnight Oil than sticking to its own strengths. "Superconductor" is far too playful to work, coming across as an awkwardly assembled novelty, a shocking misfire by a usually reliable trio of songwriters, not to mention a horrible, horrible choice as a single. While "Anagram (For Mongo)" is a worthy mellow excursion, the closing trifecta of "Red Tide," "Hand Over Fist," and "Available Light" slips into pure schmaltz, as Rush and Hine reduce the music to bland AOR fodder.

After an astounding series of high quality albums, this was the first Rush record since Fly By Night where the difference from excellent to mediocre was that wide. Still, the popularity of "Show Don't Tell" and "The Pass" helped make Presto a modest success, enough to encourage Rush to continue its partnership with Hine. Only next time, the results would be far more polarizing, and, in the opinion of many, disastrous.

When Rush's 13th album came out in late 1989, much was made about the band's purported return to the classic power trio hard rock of the early days. After a near decade of keyboard-centered forays into new wave and pop, this was Lee, Lifeson, and Peart's glorious return to rock, or as the press releases and interviews would lead folks to believe. And indeed, the band sounded a lot more robust on the lead-off single "Show Don't Tell" than they had in many years, the song kicking off with a quirky little groove that sounded lively and fun, and for many fans it was a joy to hear a new song that just had Dirk, Lerxt, and the Professor on bass, guitar, and drums. However, that brief little snippet, hyped as it was, was more of a red herring than anything else, as Presto would turn out to be yet another continuation of Rush's great pop experiment.

Replacing Peter Collins as producer was Rupert Hine, another British producer with a very strong pop/new wave background, having worked on albums by The Fixx, Howard Jones, and Tina Turner. Ironically, it would be Hine who would ease Rush out from under all the synths, resulting in an album that would make the arrangements more rock-oriented while still maintaining the strong pop sensibility of the band's musical direction at the time. However, what makes Presto such an anomaly in the band's discography is that despite bringing that traditional rock element back, it remains an oddly twee album.

Twee, but at its best, endearingly so. And the album does get off to a very strong start with four excellent tracks. "Show Don't Tell" is a prime example of Rush's skill at creating sly little prog rock suites in the pop milieu, balancing heavy rock, acoustic-tinged verses, and anthemic choruses. In lesser hands it would feel incongruous, but the way the band builds to the surprisingly graceful bridge -- with keyboards by Lee that enhance rather than overwhelm -- is masterful. "Chain Lightning" is much more conventional, perhaps a little beneath Rush, but they make it work, thanks to an affable little chorus accentuated by thin-sounding guitars by Lifeson that are so late-'80s they practically scream "Stephen Street." Equally rote is "War Paint," but the song offers a very good balance of pulsating rock and shimmering pop, culminating in a pleasing climactic chorus in its final minute. The real ace, however, is the majestic "The Pass." Prior to that song Rush's attempts at balladry always felt forced, but "The Pass" exudes grace, Peart eloquently musing about teen suicide ("Raging at unreachable glory/ Straining at invisible chains") and Lee turning in one of the best vocal performances of his career. It's a song the band remains immensely proud of -- Peart admits he gets choked up every time he plays it -- and one it still performs to this day.

After such an assured start, Presto quickly takes a turn for the worse. Featuring African-inspired rhythms by Peart and very ill-advised bass composed on sequencer, "Scars" goes awry almost instantly, the sound of a band more preoccupied with sounding like Midnight Oil than sticking to its own strengths. "Superconductor" is far too playful to work, coming across as an awkwardly assembled novelty, a shocking misfire by a usually reliable trio of songwriters, not to mention a horrible, horrible choice as a single. While "Anagram (For Mongo)" is a worthy mellow excursion, the closing trifecta of "Red Tide," "Hand Over Fist," and "Available Light" slips into pure schmaltz, as Rush and Hine reduce the music to bland AOR fodder.

After an astounding series of high quality albums, this was the first Rush record since Fly By Night where the difference from excellent to mediocre was that wide. Still, the popularity of "Show Don't Tell" and "The Pass" helped make Presto a modest success, enough to encourage Rush to continue its partnership with Hine. Only next time, the results would be far more polarizing, and, in the opinion of many, disastrous.

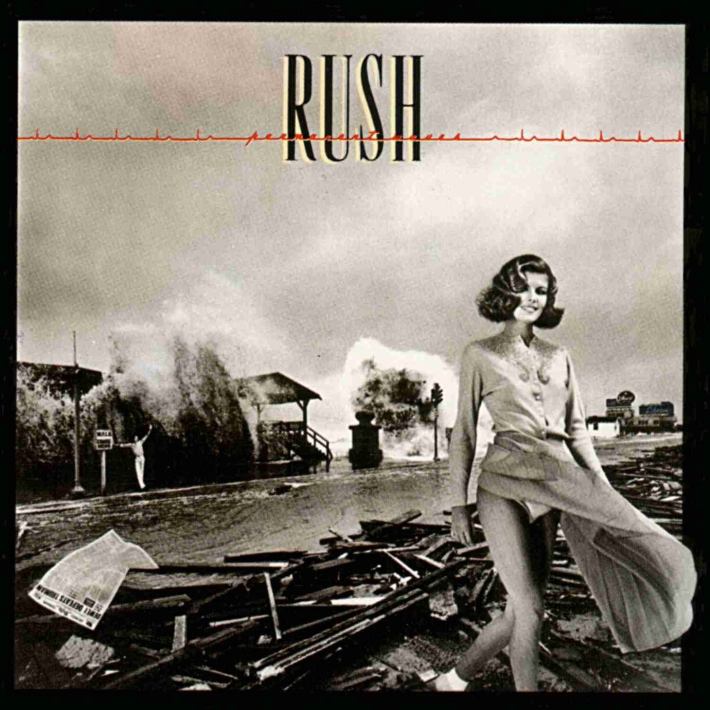

So begins Rush's Great Pop Experiment. Having first joined forces with British producer Peter Collins on 1985's Power Windows, it was clear Lee, Lifeson, and Peart were interested in exploring the more accessible side of their music. Yet even on albums as radical as Signals, Grace Under Pressure, and Power Windows, there was enough of a dynamic edge to them that served as a reminder of their power trio past. However, they were a particularly restless bunch in the 1980s, much more interested in remodeling their sound rather than pandering to fans of their 1970s era. After all, what's progressive rock without actual progression? The trouble was, in the eyes of some -- especially critics with a stodgily rockist point of view -- Rush's musical output from 1987 to 1991 was and continues to be viewed as somewhat of a regression.

Hold Your Fire was the first such album, and remains the best of the three that Rush put out during this period. Unlike the counterbalance of U2/Big Country-derived rock and cutting-edge electronics that made Power Windows so unique, Hold Your Fire is much more streamlined -- the difference between the two sides much narrower and less jarring. In other words, meeting right smack in the middle of the road. It was happening all over progressive rock in the 1980s, from Yes to Genesis, and at its best Rush's album matches the crossover likeability of 90125 and Invisible Touch step for step.

The high points are positively stratospheric, starting with the shimmering single "Time Stand Still." Featuring a memorable cameo appearance by Aimee Mann, the song contains one of the best hooks the band has ever written, sung charismatically by Lee and featuring playful instrumentation by all three members. The band's mastery of the pop form is superb as the guitar, bass, and drums accentuate the track rather than dominate, with tremendous restraint shown. The lively pair of "Force Ten" and "Turn The Page" are the closest things to hard rock on the album, its edges buffed to a sheen, while "Prime Mover," "Lock And Key," and the ballad "Mission" form a very likeable centerpiece linking sides one and two. There are a few '80s pop sins committed that stick in the craw to this day -- the horn synth stabs in "Force Ten" are unforgivable -- but Peart's lyrics are typically erudite yet personable, the big '80s optimism of the arrangements and the more introspective lyrical themes coalescing well.

After an incredible run of seven consecutive albums where a foot was rarely if ever put wrong, Hold Your Fire shows serious kinks in the armor. "Second Nature" is a little too slick, its keyboard-drenched arrangement slipping into motivational anthem schlock. Even worse is the egregious "Tai Shan," an attempt to pay tribute to Chinese classical music but comes off as hollow. The band has since conceded that the track should never have been included on the album.

Despite its slight lack of consistency, Hold Your Fire maintained Rush's impressive commercial success in the 1980s, hitting the top ten in Canada and the UK, peaking at 13 in America. Four of the album's better songs would figure prominently on the 1989 live album A Show Of Hands, showing how well they translated live. While A Show Of Hands closed out Rush's deal with Mercury in America, it would be steady as she goes for Rush on the follow-up, which would be the band's first for Atlantic Records. There might have been the odd tweak or two to the music, but Rush's gaze would remain focused on the centerline of that road for a few more years yet.

So begins Rush's Great Pop Experiment. Having first joined forces with British producer Peter Collins on 1985's Power Windows, it was clear Lee, Lifeson, and Peart were interested in exploring the more accessible side of their music. Yet even on albums as radical as Signals, Grace Under Pressure, and Power Windows, there was enough of a dynamic edge to them that served as a reminder of their power trio past. However, they were a particularly restless bunch in the 1980s, much more interested in remodeling their sound rather than pandering to fans of their 1970s era. After all, what's progressive rock without actual progression? The trouble was, in the eyes of some -- especially critics with a stodgily rockist point of view -- Rush's musical output from 1987 to 1991 was and continues to be viewed as somewhat of a regression.

Hold Your Fire was the first such album, and remains the best of the three that Rush put out during this period. Unlike the counterbalance of U2/Big Country-derived rock and cutting-edge electronics that made Power Windows so unique, Hold Your Fire is much more streamlined -- the difference between the two sides much narrower and less jarring. In other words, meeting right smack in the middle of the road. It was happening all over progressive rock in the 1980s, from Yes to Genesis, and at its best Rush's album matches the crossover likeability of 90125 and Invisible Touch step for step.

The high points are positively stratospheric, starting with the shimmering single "Time Stand Still." Featuring a memorable cameo appearance by Aimee Mann, the song contains one of the best hooks the band has ever written, sung charismatically by Lee and featuring playful instrumentation by all three members. The band's mastery of the pop form is superb as the guitar, bass, and drums accentuate the track rather than dominate, with tremendous restraint shown. The lively pair of "Force Ten" and "Turn The Page" are the closest things to hard rock on the album, its edges buffed to a sheen, while "Prime Mover," "Lock And Key," and the ballad "Mission" form a very likeable centerpiece linking sides one and two. There are a few '80s pop sins committed that stick in the craw to this day -- the horn synth stabs in "Force Ten" are unforgivable -- but Peart's lyrics are typically erudite yet personable, the big '80s optimism of the arrangements and the more introspective lyrical themes coalescing well.

After an incredible run of seven consecutive albums where a foot was rarely if ever put wrong, Hold Your Fire shows serious kinks in the armor. "Second Nature" is a little too slick, its keyboard-drenched arrangement slipping into motivational anthem schlock. Even worse is the egregious "Tai Shan," an attempt to pay tribute to Chinese classical music but comes off as hollow. The band has since conceded that the track should never have been included on the album.

Despite its slight lack of consistency, Hold Your Fire maintained Rush's impressive commercial success in the 1980s, hitting the top ten in Canada and the UK, peaking at 13 in America. Four of the album's better songs would figure prominently on the 1989 live album A Show Of Hands, showing how well they translated live. While A Show Of Hands closed out Rush's deal with Mercury in America, it would be steady as she goes for Rush on the follow-up, which would be the band's first for Atlantic Records. There might have been the odd tweak or two to the music, but Rush's gaze would remain focused on the centerline of that road for a few more years yet.

The difference between Rush's debut album and its follow-up Fly By Night is astonishing, and you hear it immediately in the opening bars of "Anthem." The blue-collar, Zeppelin and Cream-derived heavy rock is replaced by a clever blend of progressive rock complexity and heavy metal fire -- guitar and bass displaying flamboyance rather than groove, punctuated by cannonading bursts by the trio's gawky new drummer. And those verbose lyrics are a far cry from the "Hey now baby, I like your smile" of the previous album:

"Anthem of the heart and anthem of the mind/ A funeral dirge for eyes gone blind/ We marvel after those who sought/ The wonders of the world, wonders of the world/ Wonders of the world they wrought."

Indeed, Fly By Night is defined by Neil Peart, who joined Rush in mid-1974 when drummer John Rutsey was physically unable to continue touring with the band. Peart's unparalleled skill inspired Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson to step up their game, and the end result is a confident step towards a series of groundbreaking albums that took hard rock and heavy metal into strange, ambitious new territory. Additionally, it was clear the band was fully aware they needed a lyricist in a desperately bad way ("Hey, he reads books," is the famous line Lee and Lifeson cite as the reason to have Peart write the lyrics) and Peart's efforts on this album offer a glimpse at the rich science fiction and fantasy themes the band would immerse itself in over the next four or five years.

The way the band playfully tinkers with the art rock affectations of Yes, King Crimson, Genesis, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer in such an unpretentious manner is a big reason why Fly By Night is so charming to this day. Coming on the heels of the ferocious "Anthem," "Beneath, Between, And Behind" is an ebullient little three-minute electric romp that echoes English folk music, while "Rivendell" explores Tolkien themes by delving into much more restrained, acoustic fare, marking the first time audiences hear restraint from this power trio. The breezy title track echoes Yes at its most pastoral -- and a little Byrds, for that matter -- and Peart's wistful musing about leaving home for the first time has gone on to be an enduring classic rock single to this day.

"By-Tor And The Snow Dog," meanwhile, is the most important song on the album, anticipating the progressive metal epics that Rush would compose over the course of the following five albums. An eight and a half-minute suite that cleverly builds tension during a remarkable instrumental break -- led by a revelatory performance by Peart -- it also marks the first time listeners catch a glimpse of the band's uncanny knack for sly humor behind the experimental façade. Peart might have brought instrumental brilliance and literary ambition to Rush, but he also helped instill a sense of levity -- and you can't help but crack a smile upon learning that the epic fantasy tale of "By-Tor And The Snow Dog" is nothing more than a joke about how one of Rush's roadies was accosted by the two dogs owned by Anthem Records boss Ray Danniels.

As major a turning point as Fly By Night is, it's by no means perfect, and is still very rough around the edges. "Best I Can" feels like a leftover from the debut album, its pedestrian approach -- not to mention Lee's lyrics -- clashing with the ambition of the rest of the record. "Rivendell" carries on for twice as long as it should, and the seven-minute "In The End" doesn't coalesce nearly as well as "By-Tor" does. Still, Fly By Night remains a sentimental favorite of many Rush fans, the turning point where the band started to forge its own identity. The band's most definitive work was still off in the distance, but the boys were now well on their way.

The difference between Rush's debut album and its follow-up Fly By Night is astonishing, and you hear it immediately in the opening bars of "Anthem." The blue-collar, Zeppelin and Cream-derived heavy rock is replaced by a clever blend of progressive rock complexity and heavy metal fire -- guitar and bass displaying flamboyance rather than groove, punctuated by cannonading bursts by the trio's gawky new drummer. And those verbose lyrics are a far cry from the "Hey now baby, I like your smile" of the previous album:

"Anthem of the heart and anthem of the mind/ A funeral dirge for eyes gone blind/ We marvel after those who sought/ The wonders of the world, wonders of the world/ Wonders of the world they wrought."

Indeed, Fly By Night is defined by Neil Peart, who joined Rush in mid-1974 when drummer John Rutsey was physically unable to continue touring with the band. Peart's unparalleled skill inspired Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson to step up their game, and the end result is a confident step towards a series of groundbreaking albums that took hard rock and heavy metal into strange, ambitious new territory. Additionally, it was clear the band was fully aware they needed a lyricist in a desperately bad way ("Hey, he reads books," is the famous line Lee and Lifeson cite as the reason to have Peart write the lyrics) and Peart's efforts on this album offer a glimpse at the rich science fiction and fantasy themes the band would immerse itself in over the next four or five years.

The way the band playfully tinkers with the art rock affectations of Yes, King Crimson, Genesis, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer in such an unpretentious manner is a big reason why Fly By Night is so charming to this day. Coming on the heels of the ferocious "Anthem," "Beneath, Between, And Behind" is an ebullient little three-minute electric romp that echoes English folk music, while "Rivendell" explores Tolkien themes by delving into much more restrained, acoustic fare, marking the first time audiences hear restraint from this power trio. The breezy title track echoes Yes at its most pastoral -- and a little Byrds, for that matter -- and Peart's wistful musing about leaving home for the first time has gone on to be an enduring classic rock single to this day.

"By-Tor And The Snow Dog," meanwhile, is the most important song on the album, anticipating the progressive metal epics that Rush would compose over the course of the following five albums. An eight and a half-minute suite that cleverly builds tension during a remarkable instrumental break -- led by a revelatory performance by Peart -- it also marks the first time listeners catch a glimpse of the band's uncanny knack for sly humor behind the experimental façade. Peart might have brought instrumental brilliance and literary ambition to Rush, but he also helped instill a sense of levity -- and you can't help but crack a smile upon learning that the epic fantasy tale of "By-Tor And The Snow Dog" is nothing more than a joke about how one of Rush's roadies was accosted by the two dogs owned by Anthem Records boss Ray Danniels.

As major a turning point as Fly By Night is, it's by no means perfect, and is still very rough around the edges. "Best I Can" feels like a leftover from the debut album, its pedestrian approach -- not to mention Lee's lyrics -- clashing with the ambition of the rest of the record. "Rivendell" carries on for twice as long as it should, and the seven-minute "In The End" doesn't coalesce nearly as well as "By-Tor" does. Still, Fly By Night remains a sentimental favorite of many Rush fans, the turning point where the band started to forge its own identity. The band's most definitive work was still off in the distance, but the boys were now well on their way.

It goes without saying that the rock music landscape was a lot different in 1993 than it was in 1991. With the post-grunge groundswell conquering mainstream radio and indie/alternative rock and Britpop flourishing as a direct response to such blandness, veteran bands were forced to make some serious decisions if they wanted to stay relevant. Including Rush. The sleek, middle-of-the-road, pop-driven sound that dominated the band's 1987-1991 incarnation had gone as far as it could, and with sullen, gritty guitar rock suddenly becoming de rigueur, such lightweight music quickly became yesterday's news. Although it was clearly time for a shift in Rush's musical direction regardless of what was trendy at the moment, Lee, Lifeson, and Peart were absolutely aware of what was going on around them, and if there was a perfect time to return to the heavy rock of their roots, it was then.

The choice of "Stick It Out" as the first single from Rush's 15th album stuck in the craw of many fans, and for good reason. With its thick, muddy, doomy riff, slight atonality, and prototypical alt-rock beat, its intentions were clear -- just like all other classic rock and metal bands "grunge-ifying" their sounds in the 1990s -- and such a move seemed beneath these three classy fellows from Canada. As a song it wasn't bad, but it felt as shallow as such previous missteps as "Tai Shan," "Scars," and "Heresy." But what do you know, the tactic worked marvelously, as "Stick It Out" became a significant hit in America, topping the mainstream rock chart. And to the relief of fans, the rest of the new album would turn out to be much, much better than that single led people to believe.

In a period where so many older bands sounded lost as they tried to adjust to rapidly changing times, Counterparts sees Rush embracing change with typical grace and charm. The band reunited with Peter Collins, who in the time since 1987's Hold Your Fire had built up his heavy metal pedigree considerably, producing Gary Moore's After The War and Queensrÿche's classics Operation: Mindcrime and Empire. However, the bigger influence on this record would be engineer Kevin Shirley, a dynamo whose effort and input on this album would earn a unique, Steve Albini-esque "recorded by" credit. Shirley encouraged the band to thicken its sound, imploring Lee to dust off his old Rickenbacker bass and Peart to embrace a grittier drum tone. The biggest beneficiary from Shirley's input was Lifeson, the focal point on a Rush album for the first time in a very, very long time. Consequently, he sounds reborn on this album.

Indeed, once you get past "Stick It Out," Counterparts is a surprisingly vibrant album despite that return to heavier tones. Keyboards are only used to subtly enhance the otherwise power trio-oriented tracks, but when it's done, it's done beautifully, as on the excellent first track "Animate," which combines a wicked groove -- what a joy it is to hear the guys coalescing like they do here -- with a soaring, catchy chorus. The ebullient "Between Sun And Moon" lets even more light in, thanks to playful rock riffing by Lifeson and a chorus that features Lee's best singing on the record. The nervous "Alien Shore" and "Cold Fire" bring welcome energy to the album, while the surreal "Double Agent" and the whimsical, Grammy-nominated instrumental "Leave That Thing Alone" both find the band flexing its progressive rock muscle again, for the first time in forever. Forming the emotional core of the album is the heartfelt "Nobody's Hero," Peart's most poignant ballad since "The Pass" four years earlier, which is accentuated beautifully by some uncharacteristically restrained orchestration by the normally bombastic Michael Kamen.

The initial success of "Stick It Out" -- yours truly has slowly warmed up to the song in the last 20 years -- played a big role in propelling Counterparts to a surprising number two placing in grunge-obsessed America, topped only by Pearl Jam's Vs. The band would end up voicing its dissatisfaction with the album's sound and Shirley's dominance of the recording sessions, but contrary to what Rush thinks, it has aged well, one of the most underrated albums in its discography. Still, after a steady pace of albums and tours, the band was tired. It was time for the guys to slow down, and it wouldn't be for another three years until the world would hear from Rush again.

It goes without saying that the rock music landscape was a lot different in 1993 than it was in 1991. With the post-grunge groundswell conquering mainstream radio and indie/alternative rock and Britpop flourishing as a direct response to such blandness, veteran bands were forced to make some serious decisions if they wanted to stay relevant. Including Rush. The sleek, middle-of-the-road, pop-driven sound that dominated the band's 1987-1991 incarnation had gone as far as it could, and with sullen, gritty guitar rock suddenly becoming de rigueur, such lightweight music quickly became yesterday's news. Although it was clearly time for a shift in Rush's musical direction regardless of what was trendy at the moment, Lee, Lifeson, and Peart were absolutely aware of what was going on around them, and if there was a perfect time to return to the heavy rock of their roots, it was then.

The choice of "Stick It Out" as the first single from Rush's 15th album stuck in the craw of many fans, and for good reason. With its thick, muddy, doomy riff, slight atonality, and prototypical alt-rock beat, its intentions were clear -- just like all other classic rock and metal bands "grunge-ifying" their sounds in the 1990s -- and such a move seemed beneath these three classy fellows from Canada. As a song it wasn't bad, but it felt as shallow as such previous missteps as "Tai Shan," "Scars," and "Heresy." But what do you know, the tactic worked marvelously, as "Stick It Out" became a significant hit in America, topping the mainstream rock chart. And to the relief of fans, the rest of the new album would turn out to be much, much better than that single led people to believe.

In a period where so many older bands sounded lost as they tried to adjust to rapidly changing times, Counterparts sees Rush embracing change with typical grace and charm. The band reunited with Peter Collins, who in the time since 1987's Hold Your Fire had built up his heavy metal pedigree considerably, producing Gary Moore's After The War and Queensrÿche's classics Operation: Mindcrime and Empire. However, the bigger influence on this record would be engineer Kevin Shirley, a dynamo whose effort and input on this album would earn a unique, Steve Albini-esque "recorded by" credit. Shirley encouraged the band to thicken its sound, imploring Lee to dust off his old Rickenbacker bass and Peart to embrace a grittier drum tone. The biggest beneficiary from Shirley's input was Lifeson, the focal point on a Rush album for the first time in a very, very long time. Consequently, he sounds reborn on this album.

Indeed, once you get past "Stick It Out," Counterparts is a surprisingly vibrant album despite that return to heavier tones. Keyboards are only used to subtly enhance the otherwise power trio-oriented tracks, but when it's done, it's done beautifully, as on the excellent first track "Animate," which combines a wicked groove -- what a joy it is to hear the guys coalescing like they do here -- with a soaring, catchy chorus. The ebullient "Between Sun And Moon" lets even more light in, thanks to playful rock riffing by Lifeson and a chorus that features Lee's best singing on the record. The nervous "Alien Shore" and "Cold Fire" bring welcome energy to the album, while the surreal "Double Agent" and the whimsical, Grammy-nominated instrumental "Leave That Thing Alone" both find the band flexing its progressive rock muscle again, for the first time in forever. Forming the emotional core of the album is the heartfelt "Nobody's Hero," Peart's most poignant ballad since "The Pass" four years earlier, which is accentuated beautifully by some uncharacteristically restrained orchestration by the normally bombastic Michael Kamen.

The initial success of "Stick It Out" -- yours truly has slowly warmed up to the song in the last 20 years -- played a big role in propelling Counterparts to a surprising number two placing in grunge-obsessed America, topped only by Pearl Jam's Vs. The band would end up voicing its dissatisfaction with the album's sound and Shirley's dominance of the recording sessions, but contrary to what Rush thinks, it has aged well, one of the most underrated albums in its discography. Still, after a steady pace of albums and tours, the band was tired. It was time for the guys to slow down, and it wouldn't be for another three years until the world would hear from Rush again.