End Of The Century (1980)

During one of the band’s L.A. run-ins with Phil Spector, he asked the boys, “Do you guys want to make a good record, or a great one?” The question ought to have disqualified Spector; eventually, though, the Ramones granted the premise. They knew how good their output had been, but they would go to their graves believing greatness dovetails with sales. Yet Spector was an odd choice. Symbolically, perhaps, he was ideal; still, the man hadn’t produced a rock ‘n’ roll record since… well, Rock ‘N’ Roll, John Lennon’s legal-obligation record, released in ’75. Mike Chapman (whose work in the UK glitter scene suffused the boys’ early glam leanings) was in the midst of a run with Blondie that produced eight Top 40 singles and three Top 20 albums. As Stiff Records’ house producer, Nick Lowe helped maintain punk rock’s viability in Britain, helming everything from the Damned to Wreckless Eric; after the Basher split with Stiff, Elvis Costello retained his services for four more Top 10 releases. If they’d wanted someone with Sixties cred, there was a wild card: ex-Stones/Traffic/Spencer Davis Group producer Jimmy Miller, who produced Overkill and Bomber for Motorhead, but by most reports, Miller was too smacked-out to do a whole lot.

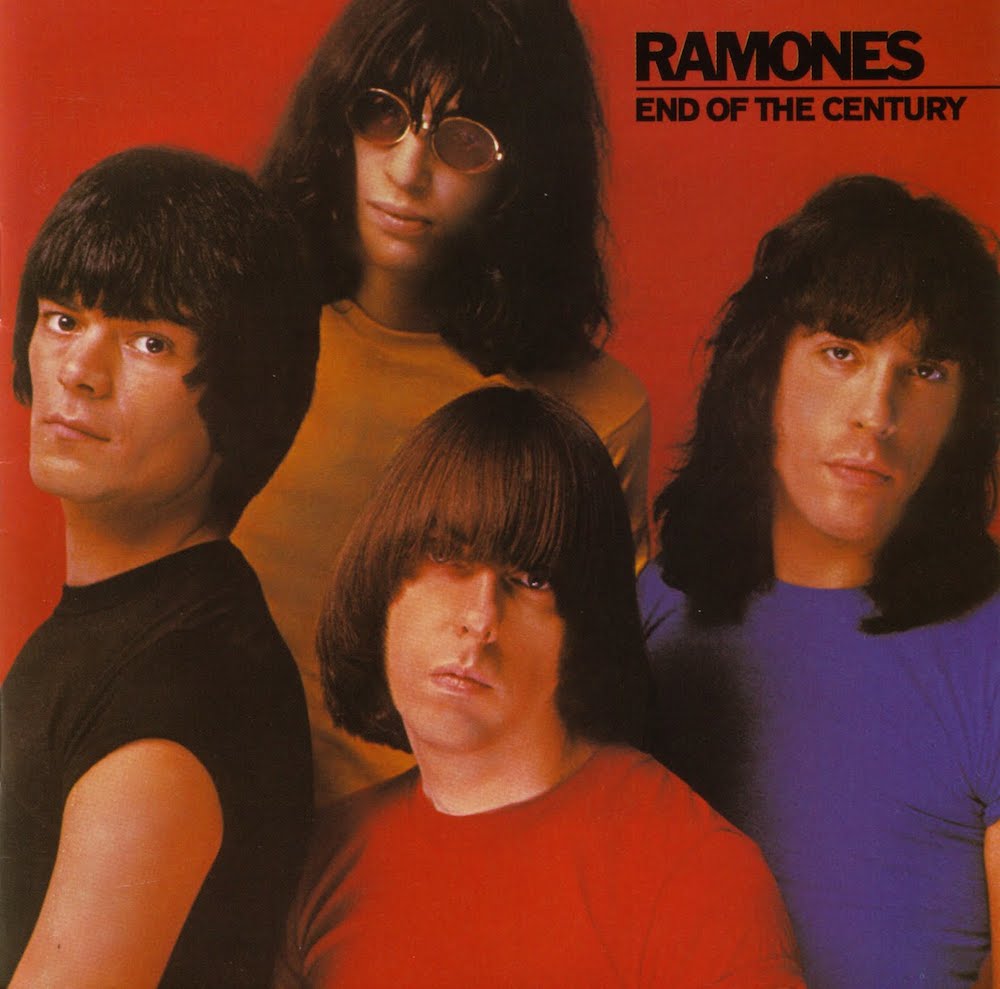

Spector, on the other hand, was a living legend, the most famous pop producer in history. He was a kid from the Bronx, a tough-talking gun toter who spent his teenage years making hits instead of breaking into laundromats. Johnny saw Spector’s hiring as a power move from Joey (reportedly, the producer kept calling the band “Joey and the Ramones”), but he was starved for a hit, so Spector it was. The End Of The Century sessions were famously fraught, completely in line with Spector’s goonish, vampiric process, but completely opposed to the Ramones’ track-quick/save-money ethos. Johnny, in particular, had a hard time of it. He chafed at replaying the same intros over and over. Dee Dee and Joey forced him to shed his leather jacket for the cover, a sort of pinup for psychopaths. (Johnny looks the roughest, his perpetually dour mug perched at a cubist angle on his neck. He settled for a jackets-on photo inside the record.) Worst of all, a few days into the process, his father died and he departed for New York. It wasn’t all rock ‘n’ roll hell, though: soon after he returned, he began dating Linda Daniele, his future wife — and Joey’s ex.

Yet, against daunting odds, the Ramones emerged with a decent record, one that mostly retained their essence. By all accounts, Spector was sincere in his love of the Ramones. He saw them as the latest link in a chain he helped forge, and thought particularly highly of Joey, whose good/bad/not evil vocal style was its own kind of throwback. The Ramones had been declared art-rockers from the jump — and a few years later would try to align themselves with the hardcore crowd — but End Of The Century demonstrated their rock ‘n’ roll bonafides. Opener “Do You Remember Rock ‘N’ Roll Radio?” made it explicit, with a fake announcer hyping the band like no pop station ever had. “Do You Remember” succeeds because it’s so desperate to ingratiate, riding in on a Bay City Rollers drumbeat, chugging along with a zippy sax section (100% George Harrison, 0% James Chance) and roller-rink organ. “Rock ‘N’ Roll High School” rides the Beach Boys to semi-immortality; the song is high-energy nonsense, but something like 72% of the words in the song are “rock,” and even though it sounds like punky ELO, it endures.

Not all the history is distant, though. A couple of Ramones classics get second chances: “The Return Of Jackie And Judy” finds our heroines at a Ramones show before getting dismissed in a gloomily modulated bridge. “This Ain’t Havana” cops the same central rhyme as Dee Dee’s “Havana Affair,” but instead of an espionage goof, it’s a mean little putdown of a welfare recipient. “Havana Affair” featured massive echo on the tom; “This Ain’t Havana” ups the stakes with a perpetually detonating drumkit. Spector even helmed their very own “Beth”: the twinkling, innocent road-band lament “Danny Says,” which takes nearly a full minute to segue from acoustic to electric guitar. It also features their first great bridge (which, again, indulges a little bit of revisionism with the line “listening to ‘Sheena’ on the radio”). If “Do You Remember” might have struck diehards as gauche, and “Danny Says” as borderline treacly, “Baby, I Love You” was absolutely treasonous. A cover of the Ronettes’ evergreen, it features one Ramone: Joey, who milks the lovesickness for everything it’s worth. Instead of castanets, there’s the god Jim Keltner on drums and clopping percussion like a medium-size time bomb. The single went to #8 in Britain, a more hospitable clime for adorable fluff.

Johnny’s on record declaring that the slower songs benefitted from Spector’s hand much more than the uptempo ones. But the punkier numbers have bite, and a lot of that is due to Spector. “I Can’t Make It On Time” would be a Ronettes tribute even without the twinkling organ on the chorus: Joey’s working a cracking, vulnerable melody, fashioning the phrase “on time” into a snug existential prison. The standard handclaps are fanned out until they sound like hedge clippers. “I’m Affected” — led in by a sterling Dee Dee bassline — veers close to the spirit of NWOBHM, helped along by massive echo on the toms and a divebombing twin-guitar attack. Speaking of Dee Dee, his “Chinese Rock” makes its Ramones debut here. Johnny originally nixed the song, so Dee Dee gave it to friend and fellow junkie Johnny Thunders. The Ramones’ take doesn’t carry the same strung-out verisimilitude, but it ups the tempo and boosts the drum gallop on the refrain. (Oddly, the Ramones did without the count-in — their bassist’s trademark — and changed a lyrical mention of Dee Dee to “Arty,” as in Arturo Vega.) Spector’s work on “All t

The Way” is worthy of Tommy’s production on albums two through four, with metallic guitar stings, Marky’s frantic pace, and angelic blocks of harmony vocals. “Doomsday’s coming – 1981,” Joey warns. (1981 is, of course, when Reagan assumed the presidency, but alas, the song was recorded before Ronnie threw his hat in the ring.)

But if their sense of history was skewed, why not their sense of eschatology? “It’s the end, the end of the seventies/It’s the end, the end of the century,” goes the key couplet on “Do You Remember Rock ‘N’ Roll Radio?” That’s a great rhyme, but it’s also a glimpse into the limits of the band’s imagination. British radio was alive with the sounds of unrest and fuckaround goofiness; American radio settled for the sonically neutered (but thematically compelling) New Wave — a term Seymour Stein desperately tried to glom onto for the Ramones’ use. End Of The Century took a couple of weeks to record and months to mix; it limped into stores in February of 1980. From start to finish, the album took almost as much time as elapsed between the release of Ramones and Leave Home. Though no singles landed, the LP nearly cracked the Top 40, and that was enough confirmation for Warner Bros. that the boys should stick to a poppier sound. The band was without Tommy, their well of compositions was nearly tapped, and they embarked on another tour with Joey and Johnny in a detente that would last the rest of their career. Meanwhile, American punk was only getting louder.