What's a legacy to a legend? For some, it's a thing to be actively patrolled: endless tours, obligatory records, the noblesse oblige of the bassist getting to do the occasional side project. Constant existence, in other words. For others, it's an ambient gift. You'll always have a band to join; awestruck journalists will check on you from time to time; people will send you messages, telling you how something you did in a small, dim room in 1968 or 1976 or 1988 or 1993 kept them alive for another day or season or year.

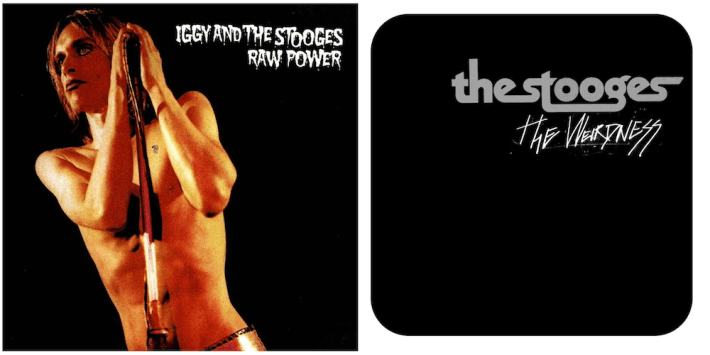

And what's a legacy to us? An objectivity, something that can be upheld or sullied. Dying young is the worst tragedy, but its best outcome is a good legacy: flash-frozen and built for wishes. For the greater part of seven decades, we've lived in an ecosystem of performers, rather than songs. Creating a great album -- hell, writing one great song -- is a feat beyond the ability of billions, but that fact hasn't prevented generations of consumers from griping about an act tarnishing its legacy. (And I'm writing as someone who once tried to convince you what Prince's 17th-greatest album is.) Bands are brands: a change in sound prompts the same hand-wringing as Apple announcing a luxury watch, or McDonald's doing McDonald’s-type social engineering things. But a band, essentially, is just a particular configuration of people working together for some number of weeks at a time. And people are a mess. Fans will live with Raw Power or Loveless or Odessey And Oracle for all time. But greatness couldn't keep the creators of those albums together.

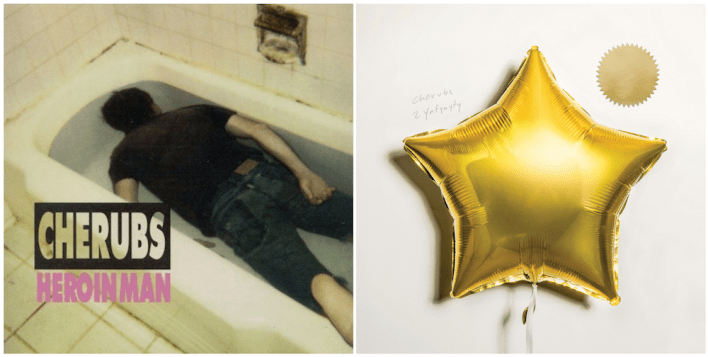

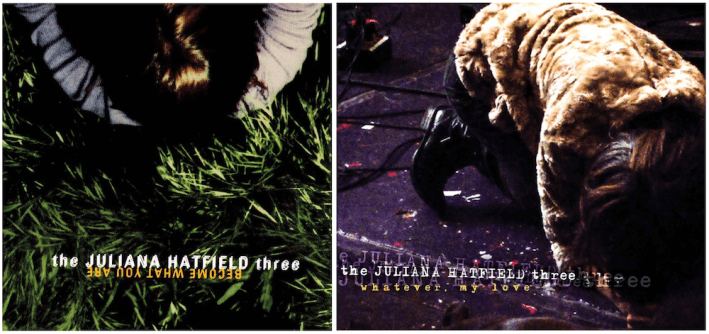

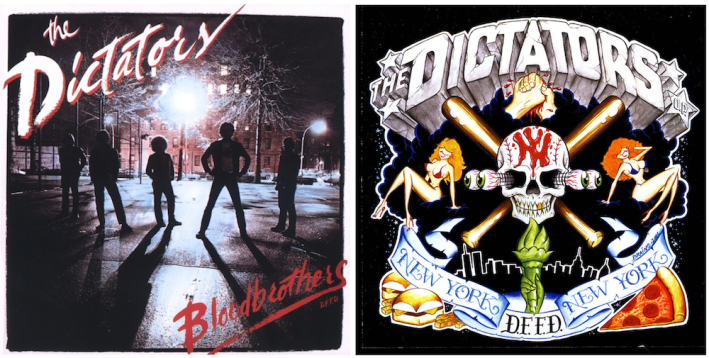

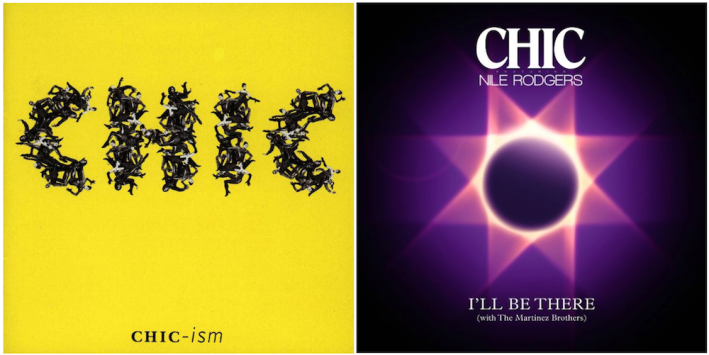

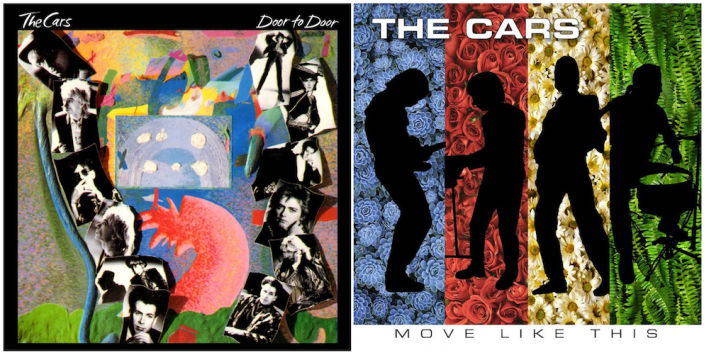

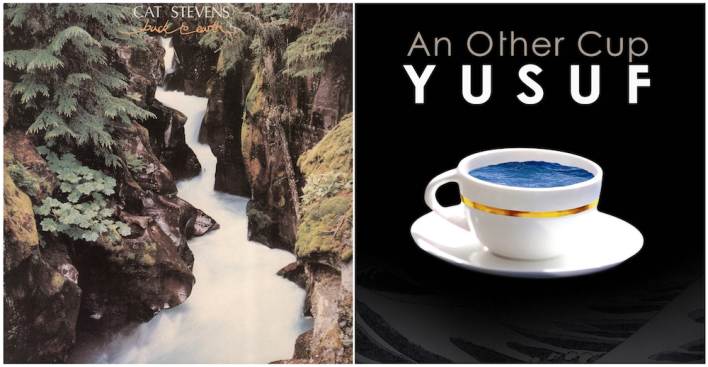

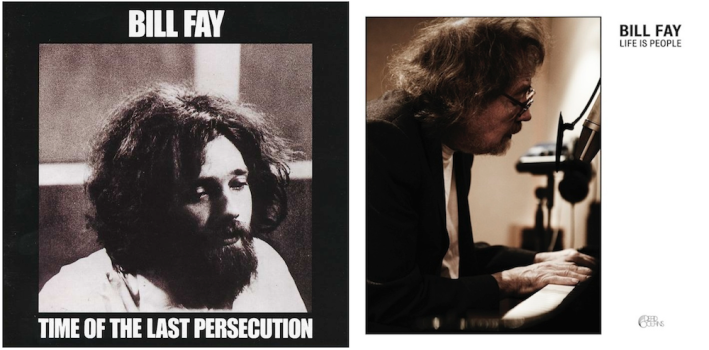

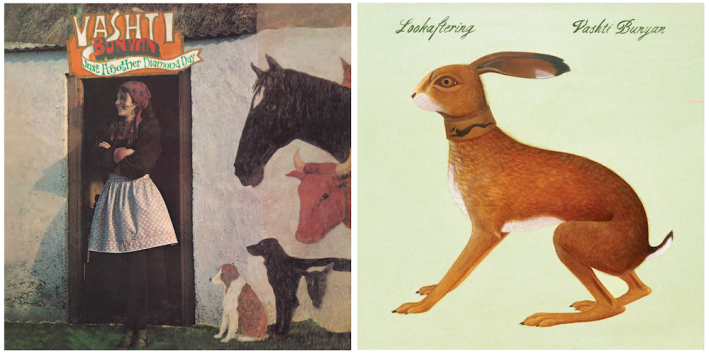

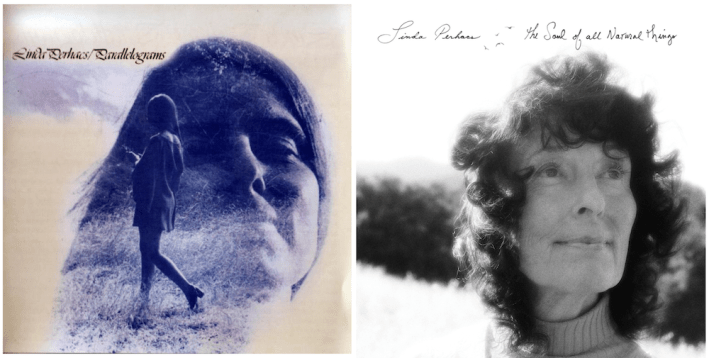

Still, greatness pulls. Each of the acts listed was eventually persuaded to release a new record, many years after the last one. For some -- the Stooges, Os Mutantes, Cherubs -- it took nothing more than the passage of time to mend old angers. For others -- Mission Of Burma, the Juliana Hatfield Three, the Slits -- the circumstances properly aligned. Others, particularly the solo artists, had done great work in secret, and the labors of collectors and bootleggers brought them back: Linda Perhacs, Bill Fay, Vashti Bunyan, Silver Apples, Death. And yeah, the allure of cash backgrounds most of these, if not all. For us, a good name is a legacy. For musicians, a good name is equity. For full-time artists in their forties, fifties, and beyond, that's a precious -- and often badly needed -- commodity.

Of the 48 acts in this list, three issued their comeback album in the '90s. Twenty-one did so in the '00s, and 24 have done it in the '10s (which, of course, we're only halfway through). Obviously, this was a self-selected crop (and many thanks go to Scott, Michael, and Erik for helping me fill in the gaps), but the trend makes sense. Boomer-era acts, by and large, aren't under pressure to generate new material. Barring the odd Stones, those groups can play the same crop of golden oldies for the same set of state fairs. It's the rock and roll version of the pension system: kinda glorious, distressingly fading. The math is different for those who hail from the Age Of Punk and onward. The combination of cheaper recording methods, digital distribution, and a sellers' market on the festival circuit makes it very tempting for alt-rock acts to bury the hatchet for as long as it takes to mount a tour and release an LP. (Or in the Pixies' case, a tour and a bunch of tepidly received EPs.) Correspondingly, it's never been easier for a music consumer to audition the comeback, to decide whether it's worth the $20 for vinyl or the $40 for a ticket.

Unlike festivals or vinyl, though, the comeback bubble will never burst. Who wants to believe that the genius seed can perish? Listening to a record has never cost so little, but the animating principle is still the same: the desire to be amazed, to learn something new. Before Marva Whitney linked up with a Japanese journeyman funk act, she'd already lived a remarkable life. But I Am What I Am offered one more tantalizing chapter. Making a great piece of music is an incredible feat, and there's nothing that can be done -- short of, say, a felony -- to erase a high-water mark. A bad album from a beloved act is a bummer, sure. But its spirit can always be glimpsed. And, if nothing else, a late-period dud points up how great the past work was, and how hard it is to match it. That's what happened for me, anyway. In putting this together, I listened to dozens of separate comebacks (not including any follow-ups). Some came from longtime favorites, and others, like the artists that released them, were totally new to me. After all that, though, I gotta tell you: there's nothing like that long pause before someone steps to the mic.

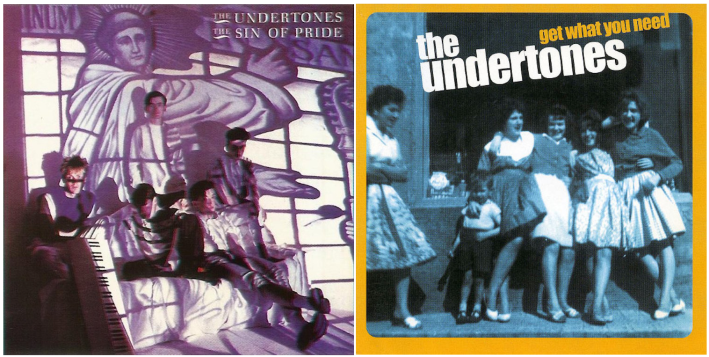

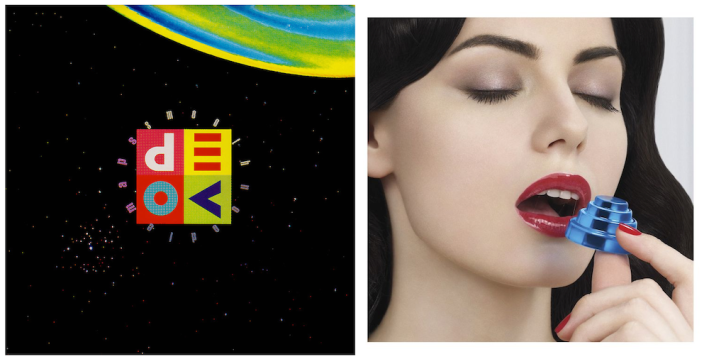

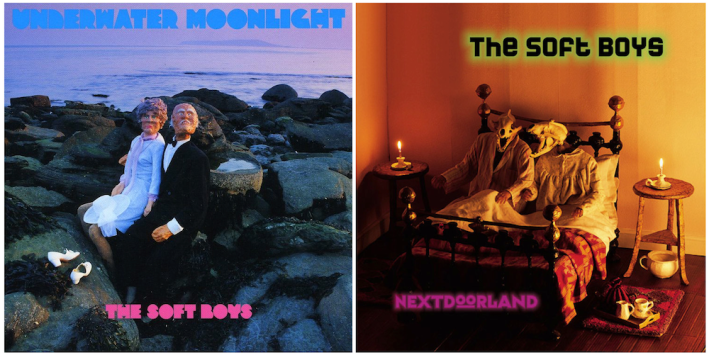

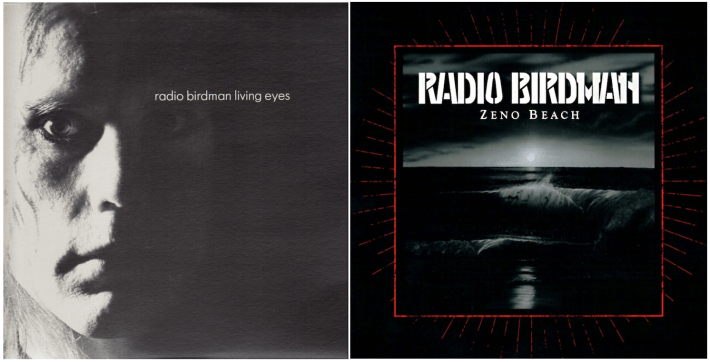

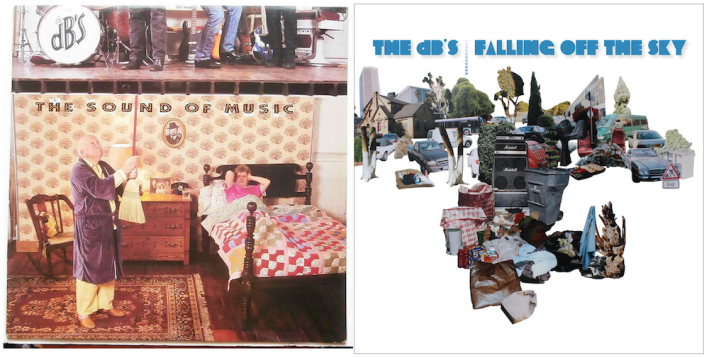

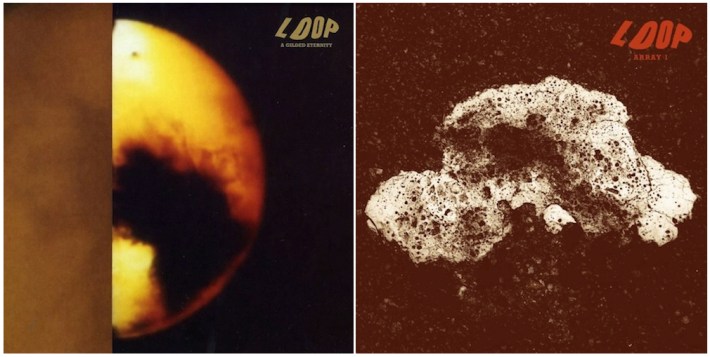

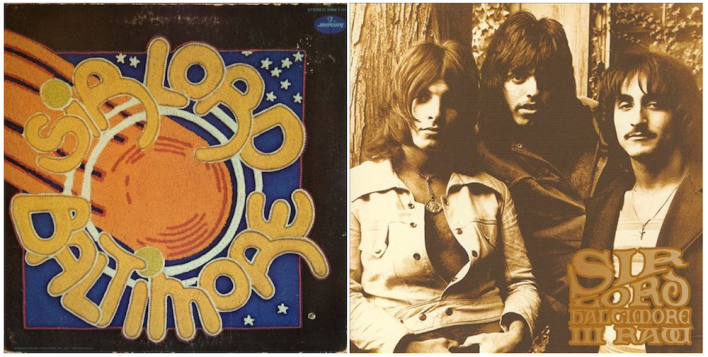

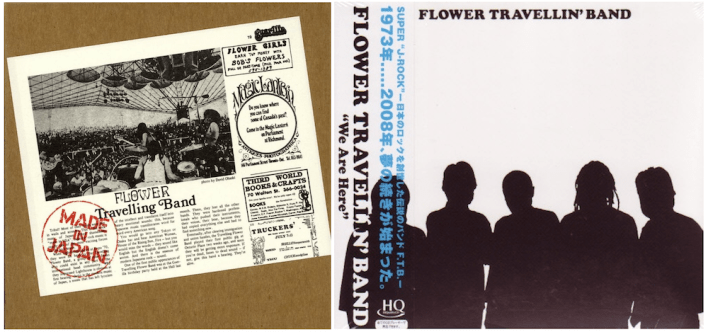

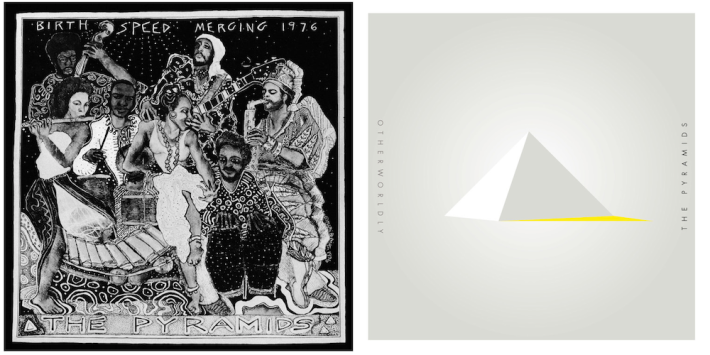

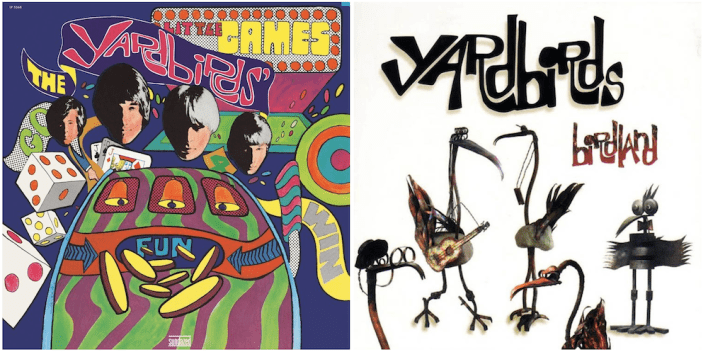

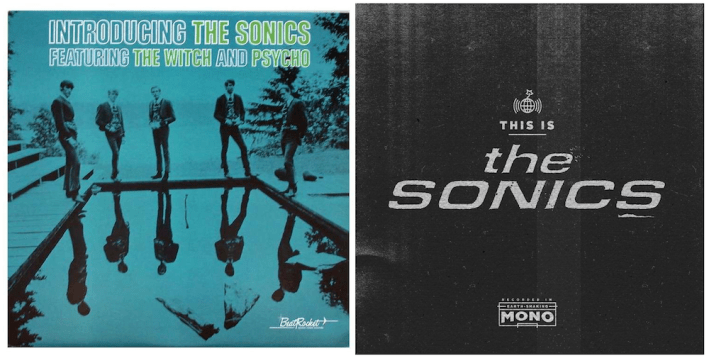

In the slideshow above is a survey of acts who went 20 or more years between studio LPs. (Twenty years based on the year of release, anyway, not the release date.) They run the gamut from genre pioneers to niche acts, from footnotes to megastars. Feel free to list any omissions in the comments. And take a second to dream about second acts not yet seen. A lot of bands from the Golden Age Of Emo are approaching two decades since the last album. (Plus there's still hope for the ultimate comeback: Paul McCartney, Rihanna, and Kanye West releasing an album as the Beatles, then watching the internet burn itself to the ground.)