During the first quarter of 2015, two artists maintained twin strangleholds on my music-related social-media conversations. The first was Björk. The second was Brian Warner, better known by his stage name, Marilyn Manson. Both are brilliant pop provocateurs and owners of uneven discographies, sometimes more famous for their clothing than their songs -- and both released their strongest albums in more than a decade this year with little to no advance warning.

That Björk merits discussion is obvious, but people's compulsion to discuss Manson now is fascinating. The man begs questions, most pertinent: Why are we still talking about him? His latest, The Pale Emperor, is the first decent thing he's released in 15 years -- not just a backhanded compliment, but a reminder that his most significant album, Antichrist Superstar, turns 20 next year.

In that timeframe, Manson's albums have felt progressively less essential (and they've sold less by the year), but he's found longevity as a spectacle and touring entity. He's headed out on a co-headlining jaunt this summer with fellow provocateur Billy Corgan and the Smashing Pumpkins. In an interview last year, Terri Nunn of Berlin told me that Manson puts on the best live show she's ever seen (tied with Rumours-era Fleetwood Mac). But his tours carry their own stigma as well: Manson feuded onstage with tourmate Rob Zombie. That recent incident follows numerous tour-related lawsuits including but not limited to sexual misconduct against a security guard in Clarkston, Michigan. At his heyday, he might have been the most hated working musician, labeled over and over as a bad influence on his young fanbase and blamed for inspiring acts of violence including the Columbine massacre.

In spite (or because) of this, his fans remain zealots. Few rock bands have whole wikis dedicated to their songs, or websites dissecting (in multiple languages) their various hidden symbols, messages, and stories, all conducted with the enthusiasm of a conspiracy-theorist community mob.

Manson's appeal remains unique, even when viewed alongside that of his most obvious predecessor: shock-rock god Alice Cooper. The Cooper comparison seems obvious at first considering their mutually feminine stage names, fixation on grotesque imagery, and paeans to young people, but it falls apart pretty quickly. While Cooper and Manson both play with horrific imagery and gender norms, Cooper's take was always more vaudeville and '50s drive-in, whereas peak Manson actually played with genuine blasphemy. And while that may seem quaint to some, such ideas still have real power in flyover states. Perhaps most importantly though, Cooper is still a blue-collar Detroit rock singer at heart -- his music appealed equally to all categories of middle American. Manson's fans, on the other hand, were part of a counterculture that was niche, even if it was pre-furnished by Hot Topic and curated by big business.

One of the keys to unlocking his uncanny appeal is the music video for "The Fight Song." Through a haze of basic-color filters, Manson repositions himself and a cadre of freaks and geeks as high school cheerleaders and football players. He put all his weight behind appealing to the people who would never achieve pubescent success in such avenues. His circus sideshow was an alternate reality wherein the outsiders took a seat at the top of the social food chain. It's nothing Kurt Cobain didn't do in the "Smells Like Teen Spirit" video, but Manson's strength was never coming up with his own ideas. He recast Cobain's disaffected "we" into an embittered "us vs. them" -- it's called galvanizing your voter base, and it's how you win a primary election in America, where Manson was never voted President Of Pop but for a good while had enough pull to keep his name on the ballot.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

And pop, really, is the point. While Manson's various tourmates (with the exception of Eminem and, arguably, Smashing Pumpkins) and cohorts aligned themselves, after a fashion, as metal bands, metal has never been an integral part of Manson's sound even though his imagery has evoked satanism and his albums to varying degrees feature gritty, distorted guitar. The primary evidence of Manson's pop core? Two of his most popular songs are covers: Depeche Mode's "Personal Jesus" and Eurythmics' "Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)." Neither of those covers are on this list, even though at this point, those covers are as ubiquitous as the original songs, at least in America, and frequently wind up on film and television soundtracks.

After peeling away the production and distortion, Manson's songs reveal a dedicated pop sensibility. In retrospect, so do many of his contemporaries in bands like Disturbed, but none of them ever hit the target so dead-on. The deluxe editions of most of Manson's albums sport a few acoustic recordings of his singles, recordings which by my estimation stand up better to repeat listens than their originals. Spoiler alert: This list boasts a lot of singles; Manson played to his strengths at least half the time. However, most of Manson's bigger, anthemic rock numbers, such as "mOBSCENE" and "This Is The New Shit," didn't make this list -- he was at his best when trying to both look and sound like an evil David Bowie. It's also why his most obvious successor is not a shock rocker, but a pop starlet: Lady Gaga, likewise a metalhead, albeit one with enough business savvy to keep that influence mostly buried.

In retrospect, aspects of Manson's career, if not his discography, remain poignant. Perhaps no single artist has mastered the music video as a medium so well, and the hoard of hidden messages and extramusical storylines and imagery woven into his album packaging and merchandise reward digging and revisitation -- every bit the carnival raconteur, he constructed an entire parallel universe for his fans to explore and dwell in, if they so chose. He offers the ephemera surrounding his music as objects to be dissected and decoded, even if his songs are less so. And while his images and lyrics are often clichéd and trite, Manson had the ability to touch on important themes of self-acceptance and individualization. One can look back at his various feminine outfits and the cover of Mechanical Animals and see an artist trying to reach out to potentially transexual fans in need of an idol. Then again, one could see him as an exploiter as well.

Manson was and remains complex: a true provocateur, one whose music affected the lives of many people, and whose influence spread into both politics and pop culture at large. He did all of these things with only a few musical tricks up his sleeve, and here we take stock in the 10 finest examples.

10. "The Fight Song" (from Holy Wood, 2000)

As stated above, Manson is normally at his best as a pop artist, one who cherry-picked from the music that preceded him to compose his own sound, at times a bit too obviously. So it is with "The Fight Song." This single from Manson's fourth album, Holy Wood, finds its most distinct moment in a clean-guitar motif reminiscent of (read: nearly identical to) the lead riff of Blur's "Song #2" -- so much so that it nearly demands a screaming "woo hoo" right before the industrial distortion kicks in to remind the listener that, yes, this is a Marilyn Manson album and, yes, the songs will alternate between softer verses and big, filthy choruses wherein the star of the show will yell something inflammatory in full expectation that, approximately on the second round of the chorus, the listener will yell it as well. Manson has written this song two to three times per album with mixed results; consider "The Fight Song" the stand-in for them all, his best attempt at heavy rotation. Holy Wood, which followed the polished and sexy Mechanical Animals, packs a particularly large stock of such songs. In retrospect it comes off as Manson's attempt at a Back In Black, a must-have disc of all singles, but unfortunately most of its tunes are too similar to one another (and too underwhelming compared to their predecessors). "The Fight Song" is the shiniest apple from that tree, due in large part to the Blur-esque verse riff, which gives things an open, jangly feel unique in his discography, one that serves as a potent counterpoint to the Mack Truck chorus. That chorus, by the way, comes off comparatively innocuous by Manson's standards, with no real mention of violence and relatively no swearing (he says "shit," if that even counts in 2015). By Manson's standards it's almost twee, rendering it sort of unique in his oeuvre.

09. "The Beautiful People" (from Antichrist Superstar, 1996)

No listing of Manson's accomplishments would be complete without discussing "The Beautiful People," the lead single from Manson's most popular album, Antichrist Superstar. It is the song that made him an icon, as well as the one most closely associated with his name. However, of all Manson's singles, it is the one least indicative of his core sound. Built around a throbbing guitar line and a swing-feeling tom-based drumline, the song ebbs and flows, spending about half of its runtime simmering under the lush production work of Trent Reznor and Skinny Puppy's Dave Ogilvie -- their subsequent absences cast a shadow on his discography, and with either of their help, some of Manson's more milquetoast later work might have sounded more subtle. As a vocalist, he pushes every facet of his limited range to the extreme here, juxtaposing hoarse crooning with punk screams, and most crucially providing a choral counterpoint to the chugging rhythm guitar. Lyrically he swings for the fences as well, referencing Nietzsche, critiquing capitalism, making dick jokes, and providing a subtle body-positive message as well. He does it all in the most surface-level way possible, but earns points for ambition. There still isn't much on the radio like it, and that it's already survived the test of time so long lands it on this list.

08. "Get Your Gunn" (from Portrait Of An American Family, 1994)

The first Manson album, Portrait Of An American Family, bears little resemblance to its successors. Deeply embedded in the early '90s alt-metal scene, it's a loose, bass-heavy, goofball affair that hasn't aged nearly as well as its successor, Antichrist Superstar, even though both were produced by Trent Reznor (it's far and away Reznor's worst turn behind the boards -- listen to how thin those guitars sound). Lead single "Get Your Gunn," however, has legs. Still one of the most controversial songs in Manson's repertoire, the number was inspired by the homicide of OB/GYN David Gunn and sports an audio sample of politician Budd Dwyer's public suicide by handgun. Under the provocation is a straightforward hard rock song, one more primitive and bellicose than the material that would follow it. Hints of Helmet crop up in the infinitely vamping verse riff, while the candy-wrapper cymbals and nail-gun snare hits in the chorus evoke Wax Trax veterans like Ministry. Equally ignorant is Manson's vocal delivery, all rasp and bile, unpolished but charming in the same way that Maynard James Keenan's hollering on Tool's Opiate EP is charming. While the remainder of Portrait Of An American Family comes across as undercooked, even for an early-'90s alt-metal album, "Get Your Gunn" feels lean and vitriolic. Sadly, Manson seldom matched its aggression again.

07. "Third Day Of A Seven Day Binge" (from The Pale Emperor, 2015)

After years of relative mediocrity, "Third Day Of A Seven Day Binge" hinted at newer and brighter prospects for Manson's future, both in terms of his artistic output and the sound of the music. A clean, clear guitar figure holds down the song's groove and melody, while harrowing guitar distortion and a straightforward dance beat flesh out the affair. It's altogether unlike the openly monstrous numbers at the core of Manson's repertoire, but it builds on his prior strengths: ballads, strong choruses, and attitude. The air of damaged glamour that permeates The Pale Emperor comes on in full force here, and with it comes a hint of growing maturity in Manson's lyrics and vocal delivery. He's still repeating the title of the song at the chorus, and still dealing with addiction and relationships at the core of his lyrics, but his approach is less rooted in the extremes of threatening or self-loathing. "Third Day Of A Seven Day Binge" deals in a few shades of foreboding gray. His languid crooning stays consistent compared to his sometimes-spotty older work, with no obvious signs of studio trickery. In fact, the key and slight tempo changes at 3:14 come across both smooth and dramatic. Stripping down his sound was a strong move for Manson, even if it only raises more Bowie comparisons.

06. "Cryptorchid" (from Antichrist Superstar, 1996)

It's easy to ignore "Cryptorchid." Tucked in the middle of Antichrist Superstar and sporting a short runtime by Manson's standards, the song comes across more like an interlude than a fully formed idea of its own (in fairness, this is true of much of the album's central segment, which pales in comparison to its blockbuster third act). However, taken on its own merits, "Cryptorchid" shines as a uniquely beautiful track, one of the few instances of Manson evoking industrial's more ambient and beautiful evolutionary tract. Remove the vocals and it could be a long lost Coil track, albeit an unusually rock-centric one. The vocals, deadpanned into a series of filtered microphones and altered by a vocoder, bear little resemblance to anything Manson has done since, though it's fun to imagine an alternative history wherein the Antichrist Superstar kept exploring this more progressive side of himself. Special note ought to be made of the wittiness in the title, which is not only a pastiche of "crypt" and "orchid," but also the medical term for testicles which fail to descend. Close listeners may be able to discern Manson whispering, "I wish I had my balls," before the song's second section.

05. "Great Big White World" (from Mechanical Animals, 1998)

Truly, Manson has only produced two albums of note: the ubiquitous industrial-metal rock opera Antichrist Superstar and its polished, glam-and-electronic-influenced successor, Mechanical Animals. While the first was a noisy, blistering guided tour through Brian Warner's journey from kitsch rock woulda-been to genuine celebrity, the second is an exposé on the dark side of that hard-earned celebrity. "Great Big White World" serves as a stunning introduction to the frigid, drug-addled hellscape of Manson's life of glitz, complete with heartless, skittering drum beats and glossy synths. The song opens at a mid-tempo creep with subdued instrumentation, adding layers of guitar and keyboard with every transition from verse to pre-chorus to chorus. When Manson croons "All my stitches itch / My prescription's low / I wish you were queen / Just for today," his lyrics zero in on a more intimate, confessional space than he previously explored, but it serves to contrast nicely with the wide, expansive music accompanying him. Reznor and Manson separated on less-than-amicable terms after Antichrist Superstar, leaving Manson to rely on bland-but-effective superproducer Michael Beinhorn to keep his sound afloat -- they leveraged his Grammy-nominated work here with NIN's old board jockey, Sean Beavan -- but the star player here is bassist/guitarist/composer Twiggy Ramirez, who has writing credits on every song (Manson does not). Ramirez's Manson band speaks many dialects of pop, and all of them are showcased in "Great Big White World," including hip-hop drum sounds, new-wave keyboard lines, and even a little R&B in the song's third act, with an overdubbed choir laying the groundwork for Ramirez's best Slash-impersonating guitar solo. This song hints at even wider, more dramatic and experimental possibilities. which, sadly, Manson has yet to reach. As an album opener, it's a powerful statement, and as a standalone song, it's one of the most audacious pieces in an otherwise conservative discography.

04. "I Don't Like The Drugs (But The Drugs Like Me)" (from Mechanical Animals, 1998)

Mechanical Animals has so many good singles that it would be easy to fill this list with all those tracks and call it a day, and while that list wouldn't represent the complete depth and breadth of Manson's output, it's equally obtuse to ignore that in 1998, Manson's commercialist ambitions and songcraft were at their respective peaks. Of those choice cuts, "I Don't Like The Drugs" is the most humorous and infectious. As far as anthems go, rock rarely gets more palm-over-face obvious -- Manson just screams the title over and over again, all the while probably wondering how nobody else thought of it first. The verse gets a little more sophisticated: muted-and-wah'd guitar coupled with Hammond Organ flourishes together evoke, of all things, Stevie Wonder, while Manson references Gil Scott-Heron, curses a white god, and opines, "I'm just a sample of a soul made to look just like a human being." The man knows exactly what he's doing. The bridge gets away from co-opting African-American music idioms, spacing out in Europop guitar, but the reprieve is short lived. An all-woman backing choir of gospel singers carries the chorus into the endzone. It's not exactly the Afghan Whigs, but it's the only time Manson ever beat Reznor to an idea.

03. "The Nobodies" (from Holy Wood, 2000)

If Manson will be remembered for one thing decades from now, it will be his relationship with his fanbase. Despite their fervor, however, Manson rarely addressed his audience through his music. "The Nobodies" is the big exception to that rule. It's a straightforward song, as Manson's anthems often are, even though tone-chasing guitarist and co-composer John 5 throws Prismacolor filth over his handful of excellent chords on the album version. The acoustic version packs equal punch, because it does less to detract from the song's centerpiece, a massive vocal hook. "We are the nobodies / We want to be somebody," Manson groans in what is maybe his most affecting chorus. The simplicity of his lyrics belies the complexity surrounding the song: "The Nobodies" was released on 2000's Holy Wood, constituting his first and most open artistic response to the Columbine massacre. The song was later featured in Michael Moore's Academy Award-winning documentary Bowling For Columbine, which Manson took part in. In his segment, when asked what he would have said to Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold -- the students behind the massacre -- Manson replies, "I wouldn't say a single word to them. I would listen to what they have to say, and that's what no one did." That sentiment is present in the song too, albeit sardonically, in the song's final verse: "Some children died the other day / We fed machines and then we prayed / Puked up and down in morbid faith / You should have seen the ratings that day." He courted controversy by taking an inclusive stance in the lyrics, as well as by naming the song after a quote by Mark David Chapman, John Lennon's assassin, but in so doing crafted one of his most empathetic numbers.

02. "The Reflecting God"

Now, the flip side of the coin. Manson's most completely heavy metal song is also his most controversial. That it's also his second-best rings as less than coincidental -- the weakness of Manson's later work (and the weakness of most late-'90s to early-aughts radio metal) lies in the inauthenticity of the feelings evoked by the music. On Antichrist Superstar, however, he comes across as legitimately pissed, and nowhere more so than on "The Reflecting God." Rumor has it that Manson played some guitar on "Gave Up" from Nine Inch Nails's spectacular Broken EP, and the influence of that record runs deepest in this song. It's a simple structure -- propulsive beats, anthemic chorus, low-string chug, and a few palm mutes for emphasis -- but one that's as primal and indelible as it was when Mötörhead wrote "Ace Of Spades." The accusations that Manson's music inspired the Columbine school shootings (as well as a few other teen suicides) stem from this song's chorus. The lyrics in question: "One shot and the world gets smaller / Shoot, shoot, shoot, motherfucker." The words function as blunt instruments, spat out over a vamping series of guitar stings. They're prime targets for misunderstanding, but they lift more raw emotional weight than some of Manson's more attenuated stabs at poetry. That said, the opening bars of this song evoke apocalypses both large and small through concise images. "Your world is an ashtray / We burn and coil like cigarettes / The more you cry your ashes turn to mud / The nature of the leeches / The virgins feeling cheated / You've only spent a second of your life." Not the most original metaphors, but they sum up all that is Manson: biblical plagues, private vices, sexual frustration, moroseness, and the American outsider-adolescent experiences (the virgins seem hardly vestal). Concerns about the song's lyrical content aren't completely without base; it addresses suicide, and posits going to heaven and telling off God as a potential merit to the endeavor. Listeners unable to see the value in that lie outside Manson's target audience. Heavy metal possesses (maybe because of social constraints more than musical strategies) a unique ability to address unpleasant but universal pieces of the human experience -- pieces like suicide. If the genre ever goes on trial again, then that ability to cope with the essential darkness of social living is its central bit of redeeming evidence. On "The Reflecting God," Manson does that aspect of the genre one solid. He addresses the subject with a battering ram, but that approach fits his idiom, and the song is stronger for it.

01. "Coma White" (from Mechanical Animals, 1998)

But as convincing and invigorating as Manson was on the heaviest songs on Antichrist Superstar, his finest moment came at the very end of its colder, more calculating sequel. In keeping with the tradition of Manson's records ending stronger than they begin, "Coma White" finishes Mechanical Animals with his balladeering at its finest. While he's never sported the strongest voice, Manson has the inflection of a trained actor, and he uses that strength to its full potential here. The ghost note of a Pinter pause before "numb" and "dumb" in the chorus comes off as a vocal tic on first listen, but after multiple listens, it reveals itself as a masterful microscopic choice. A host of devils occupy various similar details in what is otherwise a straightforward hard-rock ballad. For example, the drums skew toward the giant perfection of Mutt Lange/Def Leppard circa Hysteria, as many songs have, but on "Coma White," the snare and cymbals seem a bit damp, ringing and warbling just intermittently enough to suggest the laws of audio physics fraying at the edges. Ramirez, here playing both bass and guitar, manages to synthesize a cruel, frigid, and glitchy lead guitar tone worthy of what Adrian Belew did for Trent Reznor. His solos scratch and squeal, minor embellishments that serve as a counterpoint to Manson and his piano. "Coma White" is the closest thing to a duet ever made by the two collaborators. Inspired by the suicide of a friend, "Coma White" packages all of Manson's favorite themes -- the seductive evil of prescription medication, lost love, the paralyzing effect of celebrity culture -- into one effective vector for delivery. When he sings, "All the drugs in this world / Couldn't save her from herself," he flirts with histrionics, but never quite gets there. Manson always walks the line between entertainer and artist; the best musicians and pop stars are both, but it's a difficult balance to strike, and Manson often fell more on the entertainer side. The difference between the two, however, is a matter of fine tuning, and on "Coma White," he nailed it.

Listen to the playlist in full via Spotify.

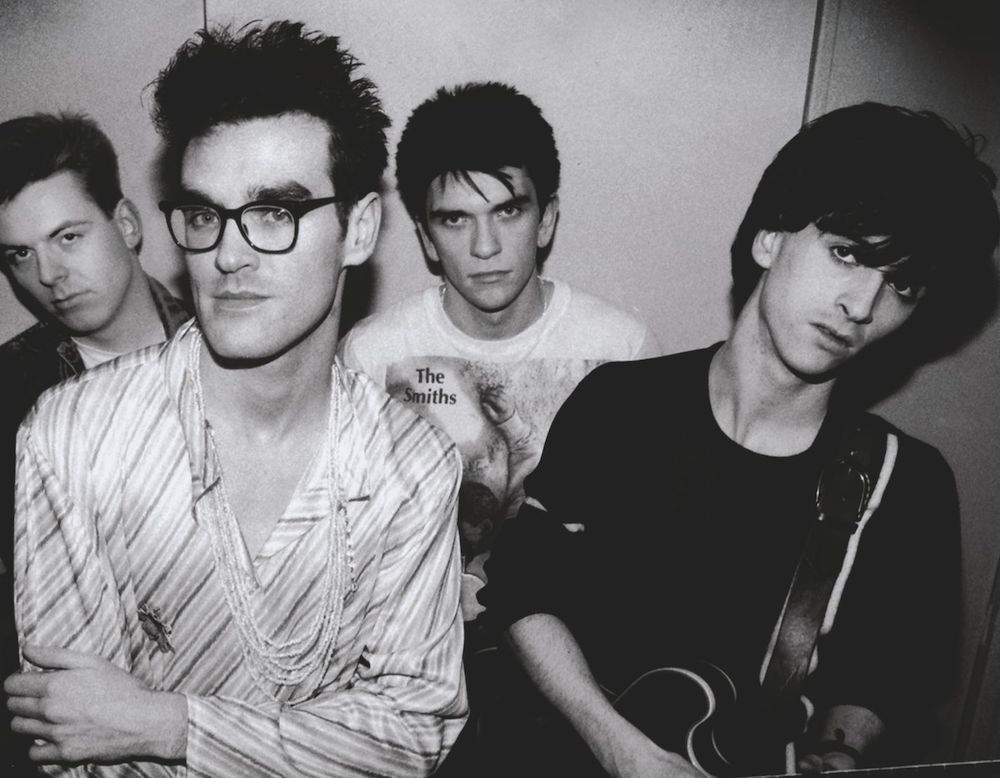

[Photo by Kelly Henderson/Toronto Star via Getty Images.]