For four decades, the great British songwriter Richard Thompson has puzzled and enchanted, menaced and soothed, and remained an enigma far too slippery to attract anything larger than his devoted cult following. Drawing from a mixed bag of influences ranging from jazz and ragtime, country, and traditional English and Scottish folk, Thompson has amassed a collection of murder ballads, spiritual ruminations, and tough-hearted rockers that ranks amongst the most formidable catalogues in recent history. As a songwriter, he holds a unique position of esteem amongst his peers. The list of prominent artists who have covered his compositions include R.E.M., Elvis Costello, the Neville Brothers, Bob Mould, Sleater-Kinney, and Dinosaur Jr., to name just a few. As an instrumentalist Thompson's reputation is every bit as glowing. Even for those not typically moved by virtuoso heroics, Thompson's guitar work is a dazzling spectacle, melding otherworldly technical proficiency with a wild-eyed inventiveness that has coalesced into an utterly a unique playing style pitched somewhere between James Burton and Charlie Christian.

As an exemplar of the phenomenon, Thompson demonstrates the manifold ways in which the "songwriter's songwriter" or "musicians musician" appellations are a blessing and a curse. To be beloved as a key influence is one thing -- to be ghettoized as a sort of favorite weird uncle is quite another. Over the decades, Thompson has bristled against these strictures, experimenting with new sounds, different producers, and a host of revolving labels in the hopes of shaking off his best-kept-secret reputation. To the extent that nothing has worked, it is probably the consequence of a deep-seated black humor that imbues even Thompson's most outwardly sincere and sentimental gestures. Vested with the same sort of contrarian streak as his rough contemporary Alex Chilton, he has largely yielded similar dividends, with the important caveat that he is still with us and making terrific music, including this year's sterling Still LP, produced by Jeff Tweedy.

Thompson began his career as teenaged guitar prodigy in the heady English folk collective Fairport Convention, a strange, almost proggy mélange of deconstructed early English music imbued with a druggy, psychedelic air. In their time, Fairport were frequently characterized as a British response to the Band, but truthfully, classic records like Unhalfbricking and Lief & Liege hew closer to the Grateful Dead -- a certain lawless democracy informing a self-contained brilliance un-replicable under any other conditions. As with the Dead, there were casualties, including the troubled genius Sandy Denny, who died under mysterious circumstances in 1978, and Fairport members Martin Lamble and Thompson's then-girlfriend Jeannie Franklin, who were killed when the band's van crashed in 1969.

Too gifted and ambitious to last long as a sideman, Thompson's early post-Fairport career was marked by a handful of classic releases alongside his wife Linda, albums that drew from the idiosyncratic traditionalism of Fairport Convention, while streamlining their sound and sharpening the storytelling. 1974's I Want To See Bright Lights Tonight and 1975's Pour Down Like Silver are unimpeachable classics of the folk genre, imbued with all of the contradictory fear, exuberance, and regret that characterized so much of the 1970s' uncertain moral vision. 1982's Shoot Out The Lights was a white-knuckling detailing of the Thompsons' painful divorce, a justifiably celebrated deep dive into domestic misery on the order of Marvin Gaye's Here My Dear and Bob Dylan's Blood On The Tracks.

Thompson's work as a solo artist has vacillated in style and approach -- from the exuberant commercial pop of Daring Adventures and Rumor And Sigh to the mostly downtrodden gestures of You? Me? Us? and Mirror Blue. Throughout, the fundaments of his persona and his uncompromising nature have never wavered. No punches pulled, no concessions made, no fabulous makeovers to appease the masses. To be a Thompson fan is to take him as he is and expect nothing else. To be fair, that isn't always easy.

On record, Thompson's worldview is a miasma of startling contradictions. A devout Muslim with a relish for licentious scenarios replete with lust, transgression, and emotional and physical violence, he charts something like a psychological middle ground between Van Morrison at his most pious and Lou Reed at his most debased. The best of Thompson's spiritual meditations -- "Dimming Of The Day" or "A Heart Needs A Home" -- are stunningly persuasive articles of romantic and religious devotion, poetic prayers of desperate longing that might stir the soul of the hardest atheist. But on songs like "I Feel So Good" or "Turning Of The Tide," he cheerfully inhabits the voice of a reckless, Luciferian figure, capable of acts of nearly unimaginable inhumanity. Thompson has a reputation as morbid performer -- a sort of "grocer of despair" in the Leonard Cohen parlance -- and it is true that dedicated depressives will find much here to feast on. But as with Cohen, even Thompson's most difficult work is leavened with humor, humanity and the possibility -- however remote -- of true spiritual redemption.

Ranking Thompson's albums is a diabolical challenge, as he's not much in the habit of making a bad record, or at least an ill-considered one. Take this list for what it's worth, give us your feedback, and most of all take the time to enjoy this wonderful talent.

As with any of Thompson's releases, 1996's double album, You? Me? Us?, contains plenty of strong songs and innovative playing, but whatever his rationale, it's not at all obvious that there is enough memorable material here to justify the vaguely exhausting 74-minute running time. Indeed the inclusion of versions of "Razor Dance" and "Hide It Away" — two good but not great Thompson songs — on both the electric first half and acoustic second half are suggestive of a dearth of inspiration quite at odds with the release's capacious ambitions. You? Me? Us? isn't a complete loss by any means — the half consoling, half threatening "Baby Don't Know What To Do With Herself" is a classic bit of black humored misery, while "She Cut Off Her Long Silken Hair" is a purely gorgeous lost-soul lament. There's probably a terrific Thompson single LP somewhere scattered over the 19 tracks here, but neither the artist nor longtime producer Mitchell Froom seems to know where to find it. After You? Me? Us?, Thompson would not release a new album for three years, and upon his return, it was with a new producer and an invigorated sound. In the meantime, he sounds ripe for a rethink.

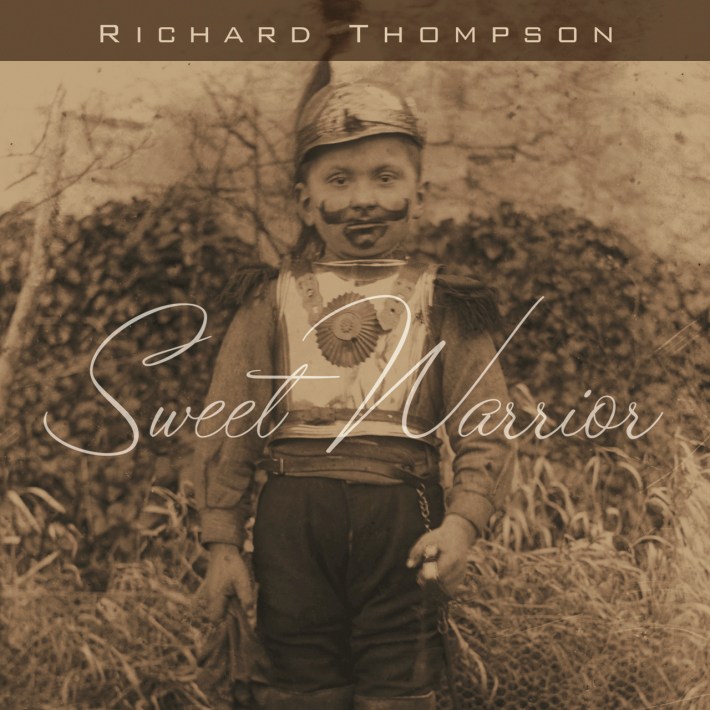

In 2003, in what could be considered a completely "on-brand" move, Thompson walked away from the majors and moved his estimable skill set over to the UK indie label Cooking Vinyl. His initial exertion as an independent artist was the entirely self-financed The Old Kit Bag, a collection of very good songs, produced very well and played very expertly by a small, but entirely competent backing band. By this point, this kind of effort from Thompson didn't (or at least shouldn't) surprise anyone – Richard Thompson is a great songwriter. The six-minute opener "Gethsemane" has both a title and a run time that should turn off most consumers, but it somehow manages to pull of the fantastic trick of being hooky and memorable while taking the time to get the point across. Thompson never sounds less than convicted in any of his performances on the record, though the songs occasionally feel like wallpaper – very nice wallpaper, but still. The title is taken from a WWI song about packing up your troubles in an old kit bag, and this definitely feels like Thompson soldiering on in typical British Keep Calm And Carry On fashion. Perhaps Thompson is shrugging it off on the heartsick, beautiful blues lament "I've Got No Right To Have It All," acknowledging that he never achieved supernova stardom at Capitol, but he sure sounds like he knows that he's not going to be fading for a long time.

2013's lean, tough-minded Electric is a self-conscious attempt on Thompson's behalf to showcase his considerable talents at bare-knuckled blues and stripped-down pub rock, a gambit that ultimately proves less gratifying than it sounds on paper. To be certain, the guitar work on tracks like the lascivious opener "Salford Sunday" and union-sympathizing "Stuck On The Treadmill" is unimpeachably accomplished, but the songs themselves frequently feel like a nothing more than a clever pretext for Thompson to go nuts. Minor-key dirges like "My Enemy" and the Alison Krauss duet "The Snow Goose" are fine compositions by the standards of most artists, but feel strangely perfunctory coming from an artist who has plowed this same terrain to far greater effect. The standout closer, "I'm Saving The Good Stuff For You," is the closest thing to a Thompson classic — a comical, ruminative and semi-apologetic acknowledgement for his renegade past, musically and thematically similar to Bob Dylan's late-career masterpiece "Mississippi" (Sample lyric: "I've had wives and I've treated them all badly/ Maybe a lover or two/ All the time oh I didn't know it/ I was saving the good stuff for you.") To be clear, nothing here is embarrassing, and quite a lot of it is highly worthwhile. But it is paradoxically the air of overarching competence that can make so many of Thompson's later records feel frustratingly indistinguishable.

A novel take on the live album, Thompson wrote and rehearsed these songs with his band before taking them on the road and recording them without overdubs in front of audiences during an American tour in 2010. The result is a muscular display of Thompson's enormous aptitude as a performer, periodically mitigated by a lack of premium songs and the difficulty of performing new music to an expectant audience unfamiliar with the source material. As experiments go, it is more than worthwhile — the bracing, banker-shaming opener "The Money Shuffle" sets a tone of cheerful malevolence, while the rockabilly-flavored miserablism of "Haul Me Up" maintains the atmosphere of genial depravity. Unfortunately, Thompson's longstanding weakness for difficult dirges raises its head on hard-going tracks like "Crimescene" and "Sydney Wells," the latter of which might have appeared as a B-side on a far less appealing version of Dylan's Desire. As with any Thompson release, there is greatness to be had here, but live energy aside, the stakes feel decidedly low.

Thompson decided to scale things back even further on his follow-up to The Old Kit Bag. This next record, Front Parlour Ballads, features almost entirely acoustic tracks performed almost entirely by a lone Richard Thompson in his home studio. While quieter, the album is still a powerful display of Thompson's virtuosity. His lyrics are no softer either – the artist has by no means lost his flair for bleak themes and gallows humor. Rollicking opener "Let It Blow" tells the story of a doomed-from-the-gate marriage of a skirt-chasing celebrity to a flight attendant and is laced with acid lines like, "And they honeymooned down in Ibiza/ Where the sun and the nightlife were hot/ As she lay on the sand, he said, 'Isn't it grand? I bring all of my wives to this spot.'" While the lovely, lilting, mandolin-inflected waltz of "Miss Patsy" is actually pretty harrowing, with everything from charismatic radicals to cyanide pills, and resolves with the protagonist in a prison cell. Thompson vents his spleen for Northwest London suburbia on the "Tombstone Blues"-esque "A Solitary Life" and spews his vitriol at a loathsome, philandering sharpie on the sparse "Should I Betray?" And then the record closes with the chilling "When We Were Boys At School," which tells the hopeless tale of a psychopath kid obsessed with Hitler and Satan who gets bullied, but grows up to have some actual social and political influence. All and sundry, the album veers between being a lot of fun to just being a lot. Still, it's refreshing to see the veteran Thompson trying something relatively new at this point in his decades-spanning career.

The follow up to 1991's sensational Rumor And Sigh largely fails to live up to the vaulting standards of its predecessor, suffering from a lack of first-rate material, an air of flagging energy, and a surfeit of studio trickery that rarely works in service of the songs. Opening track "For The Sake Of Mary" nods to Neil Young's "Cinnamon Girl" without coming close to summoning that track's manic charm, while "I Can't Wake Up To Save My Life" sounds like a pallid cousin to the barnstorming barrelhouse rock of Rumor And Sigh. In any catalog as large and diverse as Thompson's there are bound to be minor entries, and the vast majority of Mirror Blue is certainly that. That said, the record is very nearly redeemed by two classic Thompson ballads. The tenderly nostalgic "Beeswing" paints a touching picture of a long-abandoned affair, while the towering "King Of Bohemia" is a crushing tribute to a doomed friend that ranks as one of the most devastating songs he has ever delivered: "There is no rest/ for the ones God blessed/ and he blessed you best of all."

After a three-year hiatus spent on Sufi communes, Richard and Linda Thompson returned to the studio to record First Light, a largely devotional record heavy on earnestness and mid-tempo folk gestures. It's a pretty enough sounding record with some especially lovely vocals from Linda (the yearning ballad "Strange Affair" is a real highlight), but it generally feels de-fanged, lacking in humor and seems kind of rudderless. Which is fine – spiritual searching is murky business and this isn't a bad album, it's just a little boring when compared to Richard and Linda's previous output. Richard's vocals are largely buried on the opening tale of wanderlust, "Restless Highway," such that you almost miss his funny litany of things he's willing to do (milk cows, solder stuff, hit you in the nose, whatever you fancy) to earn his keep as he rolls along on his journey. Meanwhile, the bass-driven, ersatz disco-funk on "Don't Let A Thief Steal Into Your Heart" certainly feels of its time, but a bit of a head-scratcher on this particular collection of songs. The paired "The Choice Wife/Died For Love," which clocks in at more than 9 minutes, fits into the tradition of folk storytelling well, but it shouldn't be this long. The record closes with the overtly spiritual title track that features some interesting guitar work on an album largely devoid of Richard Thompson's innovative playing. In all, First Light feels like an ambivalent offering from an artist who is trying to reconcile how to stay on a traditional career path during a spiritual quest.

Throughout the 1980s and into the early 1990s, a strain of belief persisted within the record industry that Thompson might yet emerge a genuine commercial commodity, at least on par with similar-minded contrarians like Elvis Costello and Lou Reed. In truth, Thompson's muse always veered a bit askew for that kind of commercial embrace, but efforts were accordingly made to update the singer's traditional-minded song craft with a contemporary studio sound. The results of these efforts range from the sublime to the borderline unlistenable, sometimes within the course of the same side of music. Such is the case with Amnesia, which kicks off with a terrific power-pop reading of one of Thompson's catchiest-ever tunes, "Turning Of The Tide," a could-have-been hit which wouldn't have sounded out of place on Document or Flip Your Wig. Regrettably, tracks like the weary blues of "No Gypsy Love Songs" and the acidic geo-political agitprop of "Yankee, Go Home" fare less well amidst the layered synths and gated drums of producer Mitchell Froom. As Thompson albums go, Amnesia is half good, which for a performer of his magnitude means it is still well worth hearing. Standouts like the slow-burning "The Reckless Kind," the spiteful "Jerusalem On The Juke Box," and especially the excellent ballad "Waltzing For Dreamers" ensure that Thompson can still deliver the goods amidst all the whistles, bells, and cluttered backing.

Thompson's last album of the 1990s is still another strong outing in the career of this most consistent of recording artists. An engaging series of dark character sketches and creepy-nostalgic reminisces of the England of his boyhood, Mock Tudor is an impressive instance of world building through song craft, vivid in detail and bracing in execution. Emphatic opener "Cooksferry Queen" is a lurid love letter from a criminal to his chosen moll, while the rockabilly-flavored "Two Faced Love" is the sort of morbidly funny meditation on love and mendacity which Leonard Cohen has made a cottage industry of in his later years. Meanwhile the gorgeous soul ballad "Dry My Tears And Move On" is the kind of vintage lament that makes one wish Otis Redding were still here to provide a reading, or that maybe Rod Stewart or Van Morrison will get there yet. Meanwhile, the eerie minor-key closer, "Hope You Like The New Me," ends things on an anxious, menacing note, with the singer threatening a perceived rival with a callousness bordering on chilling. Tough and unsparing, Mock Tudor finds Thompson very much in control of his gifts three decades into his career, with no perceivable threat of going soft.

The cover of Richard and Linda Thompson's 1979 Sunnyvista features a Technicolor family looking positively ecstatic as they stand in front of a completely drab and gray development. And the material on the record follows the image – Sunnyvista is a collection of mostly upbeat-sounding, uptempo songs that deal with some pretty heavy subject matter. Opener "Civilisation" presents xenophobia and suburban ennui with a kind of gleeful ambivalence that almost could pass for Devo, if Devo played accordions instead of synths. Meanwhile, the title track presents the luxury of leisure time afforded by post-industrial innovation and automation, and the proliferation of prefabricated homes in planned communities that provide places for kids to play safely, adults to socialize freely, and the aged to die gracefully – and it sounds terrifying. Of the couple of devotional offerings on here, "You're Going To Need Somebody" stands out as an incredibly catchy recital of faith. And the politically charged funk of "Justice In The Streets" features a singalong refrain of "Allah, Allah, Allah" to buoy lyrics like, "They fooled you for so long/ You can't tell right from wrong/ They are weak and you are strong/ There's justice in the streets." Abetted by some serious talent – vocals by the McGarrigle sisters and Glenn Tillbrook, and a lot of excellent accordion playing by John Kirkpatrick – the principals have a lot of the makings of a great record here, but there are too many genre experiments, and the result is something merely very good but definitely very interesting.

"Same old, same old" – so goes the refrain on "Pony In The Stable," one of the dozen tracks on Richard Thompson's 2015 Still – a sentiment that more or less sums up the artist's most recent effort to date. Which is to say it's exactly what we've come to expect from Thompson by now: a really great collection of songs, complete with inventive guitar playing, fully drawn character studies of lonely outcasts ("Josephine"), conniving outlaws ("Long John Silver”), and difficult lovers ("All Buttoned Up"), and everything from aesthetic nods to Fairport Convention ("She Could Never Resist A Winding Road") and explicit references to the Geneva Convention ("No Peace, No End"). In between, there's the autobiographical tale of Thompson's time spent in Amsterdam, "Beatnik Walking," as well as the more overtly political "Dungeons For Eyes." And Thompson ties everything off with a very funny novelty song called "Guitar Heroes," about a guy who really likes to play the guitar at the expense of everything else in his life, that has as many shoutouts to the greats as Arthur Conley's "Sweet Soul Music," but does it one better by actually playing in the style of each of his idols. It shouldn't work, but it does, because Richard Thompson is often at his best when he lets himself be silly. For this record, Thompson recruited Wilco's Jeff Tweedy to produce, and the results are immediate and satisfying, even if neither Tweedy nor Thompson seems particularly inclined to color outside the lines.

Thompson's return to electrical form after 2005's Front Parlour Ballads is an expansive and energized affair that finds the artist so exercised about the current state of America's involvement in the Middle East that the release can be considered as much a piece of savage agitprop as just another Richard Thompson record. The typical mid-tempo tracks about heartache and more heartache are largely jettisoned here in favor up-tempo material replete with visceral, frequently violent imagery. Thompson seems equally concerned with taking up the torch for frontline soldiers as he is making a more global statement about a pointless war fought for pointless reasons by foolish people. The two standout tracks, "Dad's Gonna Kill Me" and "Johnny's Far Away," explore the terror of going to war ("You hit the booby trap and you're in pieces/ With every bullet your risk increases") and the post-traumatic hell that awaits when you get back ("Johnny's home, he opens up his door/ While someone's sneaking out the back/ And Tracey says, you look so poorly/ Sores and all, you need to see the quack"). Even the less explicitly anti-war cuts are pretty brutal – the entirely danceable ska track "Francesca," bitterly culminates with the crushing couplets, "Who laid her down, took her rose/ Who took her flower/ Now she charges by the hour/ Left her the whore of the world." In Thompson's world there are no heroes, just the exploiters and the victims.

By 1986, Thompson's evolution from a traditional folk performer into a more conventional but still profoundly compelling rock and pop performer was just about complete. The strong solo albums Hand Of Kindness and Across A Crowded Room had impressed critics, but failed to sell, and Daring Adventures finds Thompson under commercial pressure from his label to produce a hit. No hit was forthcoming, although the buoyant, sardonic "Valerie" by all rights should have fit the bill. Instead, what the record company got was another in a line of sharp, well-conceived rock albums replete with strong, clever songs, magnificent playing and lukewarm public appeal. No accounting for taste, but consumers will find plenty to enjoy on Daring Adventures, including the scenester-baiting opener "She Hasn't Got A Bone Through Her Nose," the stunning, melancholy waltz of "How Will I Ever Be Simple Again," and the vituperative emotional hatefuck of "Jennie" (although the latter is much better heard in the live version featured on the 1993 Watching The Dark compilation). Like Elvis Costello's Trust or Van Morrison's Common One, Daring Adventures is an accomplished release by a terrific artist that doubles down on his talents without straining to reinvent the wheel or repurpose his approach. It's not necessarily a place to start, but if you like the things Thompson does, you'll be more than happy to own a copy.

1985's bitter, frequently brilliant Across A Crowded Room kicks off with one of Thompson's best-loved paeans to broken love and busted emotional circuitry, "When The Spell Is Broken," and continues on in that fashion for nearly 40 minutes of pitiless romantic cynicism and acid social critique. Tense, unsparingly angry, up-tempo tracks like "You Don't Say" and "Little Blue Number" strongly suggest the influence of new wave in general and Elvis Costello's menacing take on traditionalism specifically, agreeably updating Thompson's sound in the most organic manner possible. In the meantime, "Fire In The Engine Room" is a straight rave-up that wouldn't feel completely out of place amidst the emotional and literal violence of Exile On Main Street, while "Walking Through A Wasted Land" proceeds patiently through Great Britain's slow decay under Margaret Thatcher. Closer "Ghost In The Wind" is fearlessly ugly and beautiful, featuring Thompson's detuned guitar set to a noir-ish lyrical tableau consisting of broken dreams, abandoned homes, and apparitions who might not actually be dead. Nothing the similarly sounding Sonic Youth accomplished at the peak of their considerable powers was ever more trenchant or disturbing.

Thompson's first record without his former wife Linda by his side since 1972, Hand Of Kindness is a strange, engagingly exuberant affair, suggestive of an individual enjoying a heedless bender at the end of a long and unpleasant ordeal. Opener "Tear Stained Letter" sets the template with its rollicking, accordion-aided tale of cheerful, balls-out debauchery ("My head was beating like a song from The Clash/ I was writing checks that my body couldn't cash"). Meanwhile "Both Ends Burning" takes the party to the racetrack for a mirthful, decadent romp serving as a kind of thematic forerunner to the Hold Steady's classic "Chips Ahoy," and "Where The Wind Don't Whine" finds the singer on an age-inappropriate romantic rebound. At points the exuberance works at crossed purposes — the crushing ballad "Devonside" functions much better in subsequently released stripped down versions — but all in all, it is difficult to find fault with these hard-headed, tough-skinned acquiescences to the life of a single man and a solo artist.

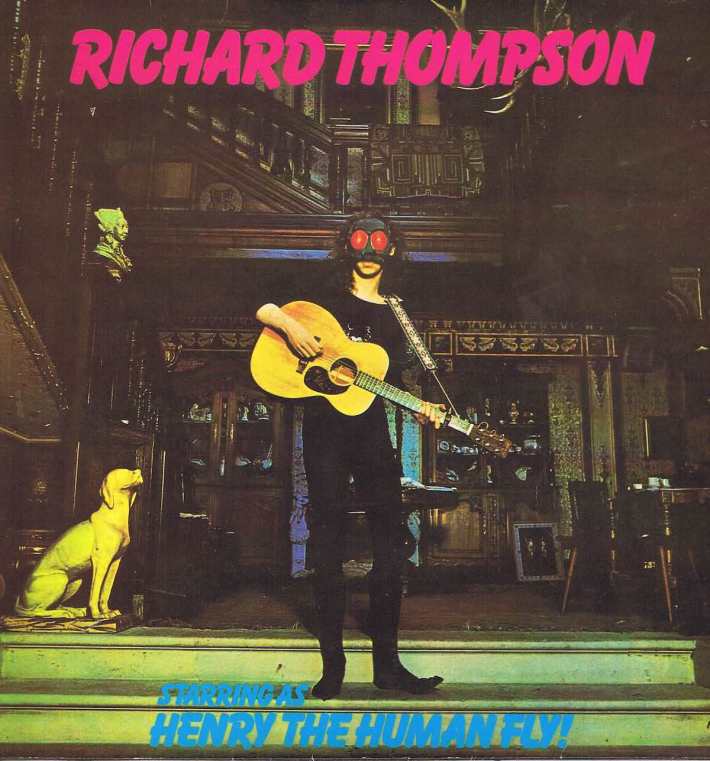

Thompson has often bragged that his 1972 solo debut was the quickest deletion in the history of Warner Bros. records, a perhaps apocryphal claim that nevertheless underscores the deafening critical and commercial silence that greeted the album's release. Forty-five years on, it isn't hard to extrapolate why the record failed to catch on — Thompson's set of rocked-up folk sought to hybridize his background and influences, but did so a little too effectively, proving too bracing for folk purists from the Fairport Convention camp and too subtle for fans of the Who and Led Zep's maximum R&B. Time has been kind to Henry The Human Fly, and it sounds fresher and more vibrant today than the vast majority of the roots-based music of the period. Typical of Thompson, Henry The Human Fly is replete with tough, uncompromising material. Hard-riffing opener "Roll Over Vaughn Williams" strikes an ominous tone, unspooling tales of London gutter life, mythologizing violent street urchins and admonishing those who "live in fear." "Poor Ditching Boy" sets a beautiful melody to a tale of brutal physical and spiritual deprivation, while even comparatively winsome tracks like the up-tempo near-pop of "The Angels Took My Racehorse Away" ponders the death of a beloved animal companion. As a fitting introduction to Thompson's unique moral and spiritual worldview, Henry The Human Fly is largely terrific. As a spectacular commercial failure it would set a different, less desirable template — that of a dazzling talent whose singular, dyspeptic vision would prove too difficult for a wide swath of consumers to metabolize.

Leave it to Richard Thompson to see to it that his closest-ever flirtation with an actual hit single is an inescapably infectious sing-along told from the perspective of a psychopath bent on an evening of rape, murder, and mayhem. That would be "I Feel So Good," the second song on Thompson's 1991 tour-de-force Rumor And Sigh, a remarkable album filled with a plethora of delirious hooks and perverse, menacing thrills. "Read About Love" kicks things off with a driving, Townsend-esque rocker about sexual alienation and progresses through a veritable encyclopedia of social and psychological dysfunction on tracks like "I Misunderstood" ("I thought she was saying good luck/ She was saying goodbye") and the gutter rat's prayer "God Loves A Drunk." Perhaps most notable is the noir-ish tale of a doomed criminal and his prized motorcycle, "1952 Vincent Black Lightning," a staggering showcase for Thompson's storytelling and playing that rates amongst his acknowledged masterpieces. Overall, Rumor And Sigh is as direct an album as Thompson has ever made, sharpening his focus down to its most accessible elements, while sacrificing none of his black-humored vision.

The second in a triumphal three-record run of masterpieces released between 1974 - 1975, Hokey Pokey finds Richard and Linda firing on all cylinders over the course of an ebullient, tragicomic set of debauched character studies and soaring spiritual ruminations. From the jaunty, thinly veiled ice cream double entendre of the opening title track, to the jaw-droppingly lovely penultimate ballad "A Heart Needs A Home," there is rarely a false note present. Amongst the many highlights is the frighteningly raw confessional "I'll Regret It All In The Morning" ("Whiskey helps to clear my head/ Bring it with you into bed/ If I beat you nearly dead/ I'll regret it all in the morning") and the rueful waltz "The Sun Never Shines On The Poor." Full of sharp writing and energetic, engaging performances, Hokey Pokey brilliantly invigorates the traditional music that undergirds all of the Richard Thompson catalog. That it is only the third-best record they would release in an 18-month period is testimony to just how high a level the duo were working at during the mid '70s.

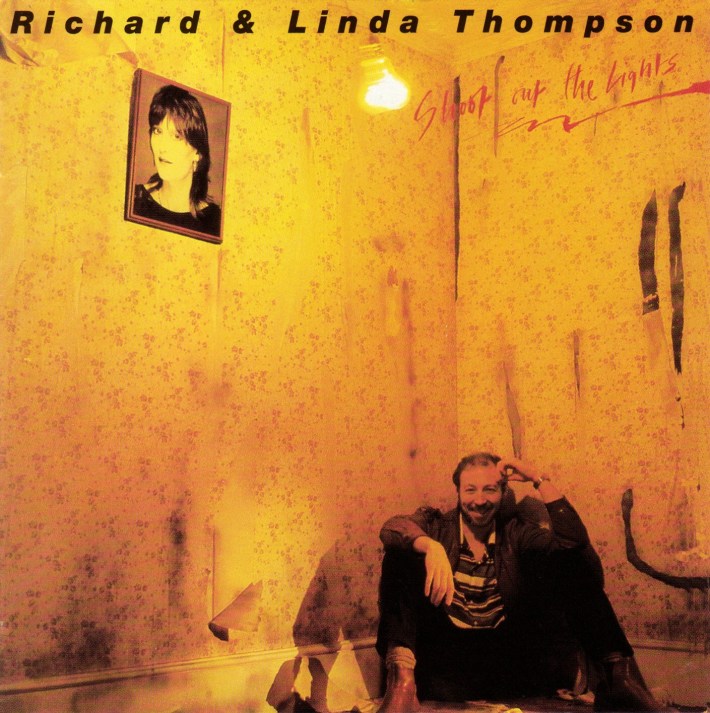

Recorded amidst a period of intense personal and professional turmoil, the final Richard and Linda Thompson album is a wrenching document of fraying domesticity and dashed artistic dreams. Dropped from their label, Chrysalis, following the lukewarm response to 1979's Sunnyvista, the ensuing two years had been endlessly trying for the couple. By the time Shoot Out The Lights was released in 1982, their marriage and creative partnership was functionally over, a fact that made the ensuing, contractually obligated support tour close to unbearable. Even given this fraught context, the temptation to characterize Shoot Out The Lights as a typical "divorce album" is reductive and diminishing. Rather then an intimate portrait of one couple's experience, the record is more like a triptych of entropy — the existential nightmares of such key tracks as "Did She Jump Or Was She Pushed?" and "Wall Of Death" amounting to something bigger than the hill of beans that is two people's problems. Far from feeling defeated, the music here is by and large an exposed nerve of energized longing — angry, frightened, and contrite in equal measures. The jaunty desperation of "A Man In Need" and the rollicking, vaguely threatening "Don't Renege On Our Love" are frenetic articles of dead-letter devotion, haltingly suggesting a way forward for the partnership. Only on the brooding title track's dissonant, epic guitar outro do we fully recognize the marriage's lost cause, spoken through Thompson's instrument in a manner that his potent words can't quite bring themselves to express.

Leading up to 1974's landmark I Want To See The Bright Lights Tonight, Richard Thompson had long been striving to co-mingle his dueling impulses toward adventurous rock and traditional folk. Here the job gets done, and the results are nothing less than revelatory. Beginning with the insistently strummed folk-rock opener "When I Get To The Border" and buttressed by the avant-tinged guitar freakout "Calvary Cross," Thompson has established a new vernacular for traditional music, nearly as impressive in its way as the Velvets' co-mingling of experimental composition and Tin Pan Alley craftsmanship. Juxtaposing the woe-begotten romance of tracks like "Does He Have A Friend For Me" and "Withered And Died" with the winsome, triumphal sing-along of title track and derelict's roadmap "Down Where The Drunkards Roll," Thompson accomplishes an extraordinary amount of world building here — populating his songs with the sort of indelible musical and literary textures that would later make the Pogues so transporting. As with an English winter, the darkness can verge on unsparing — addressing an infant on "The End Of The Rainbow," Thompson proceeds through a litany of life's miseries that the tyke can look forward to, beginning with the memorable opening couplet: "I feel for you, you little horror/ safe at your mother's breast." Closer "The Great Valerio" brings the curtain with an appropriately tense story of a tightrope walker tempting catastrophe, or perhaps asking for it: as good a metaphor as any for the high-wire act Thompson has pulled off in rendering this unique masterpiece.

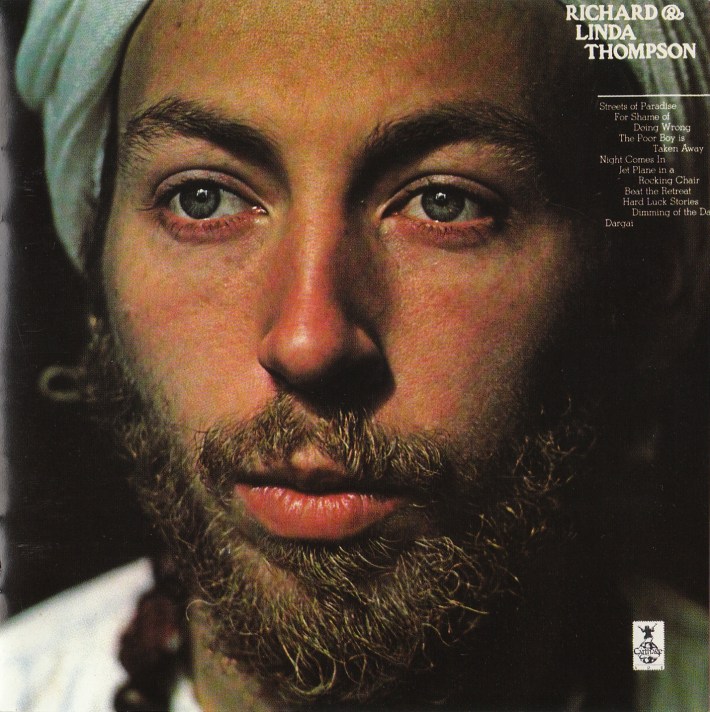

In a single potent stroke, 1975's Pour Down Like Silver distills all of the romance, comedy, terror, devotion, and lust which, taken together, comprise Thompson's brilliantly singular genius. From the fretfully exuberant opener "Streets Of Paradise" ("Tears fall down like whiskey/ Tears fall down like wine/ On an island made of cocaine/ On a sea of turpentine") to the astounding eight-minute side one closer "Night Comes In," it is apparent that we are in rarified, roiling emotional terrain. All of that is mere pretext to the flip side, roughly 21 minutes of near-total transcendence resembling nothing so much as side three of Exile On Mainstreet in all of its beautiful, terrible reckoning. Even amidst the ostensible optimisms of "Jet Plane In A Rocking Chair," the tugging undertow of fractious human interaction holds true. On the almost unimaginably harsh and beautiful ballad "Beat The Retreat," Thompson lays bare a loneliness so visceral it feels frighteningly innate to the human experience. "Dimming Of The Day/Dargai" is probably Thompson's greatest song, and one of the great album closers in all of the popular music tradition — a near-perfect meditation on love, nature and religious salvation that stands shoulder-to-shoulder with behemoths like Ray Davies' "Waterloo Sunset" and Bob Dylan's "Blind Willie McTell" in the tower of song. Thompson has continued to render great music for decades after Pour Down Like Silver, but he has never yet surpassed this colossal achievement.