Irony has claimed a lot of casualties over the years, but it's just about time to examine whether alt-rock's fate as one of them was self-inflicted or a hit job from outside forces. If that sounds like a self-serious way to examine our relentless winking "Hey, remember the '90s?" moment -- one that's been portrayed as Gen X's midlife crisis butting up against a Millennial wistfulness for an ideal moment since destroyed -- well, I'm sorry. I'm just still doing what I can to cope with the fact that the people who gave us the buttrock jukebox musical Rock Of Ages are trying to do the same thing with a lot of the songs that gave voice, flawed as it might have been, to a bunch of shitty teenage feelings my Class-of-'95 self and a lot of other staring-down-40 people have tried to put way back in the rearview. We just got over Moulin Rouge, damn it! What are you even fucking doing? Can we at least be straightforwardly sincere about a single thing we grew up with for once? And not, like, Nicktoons, I mean something that actually steered us toward adulthood.

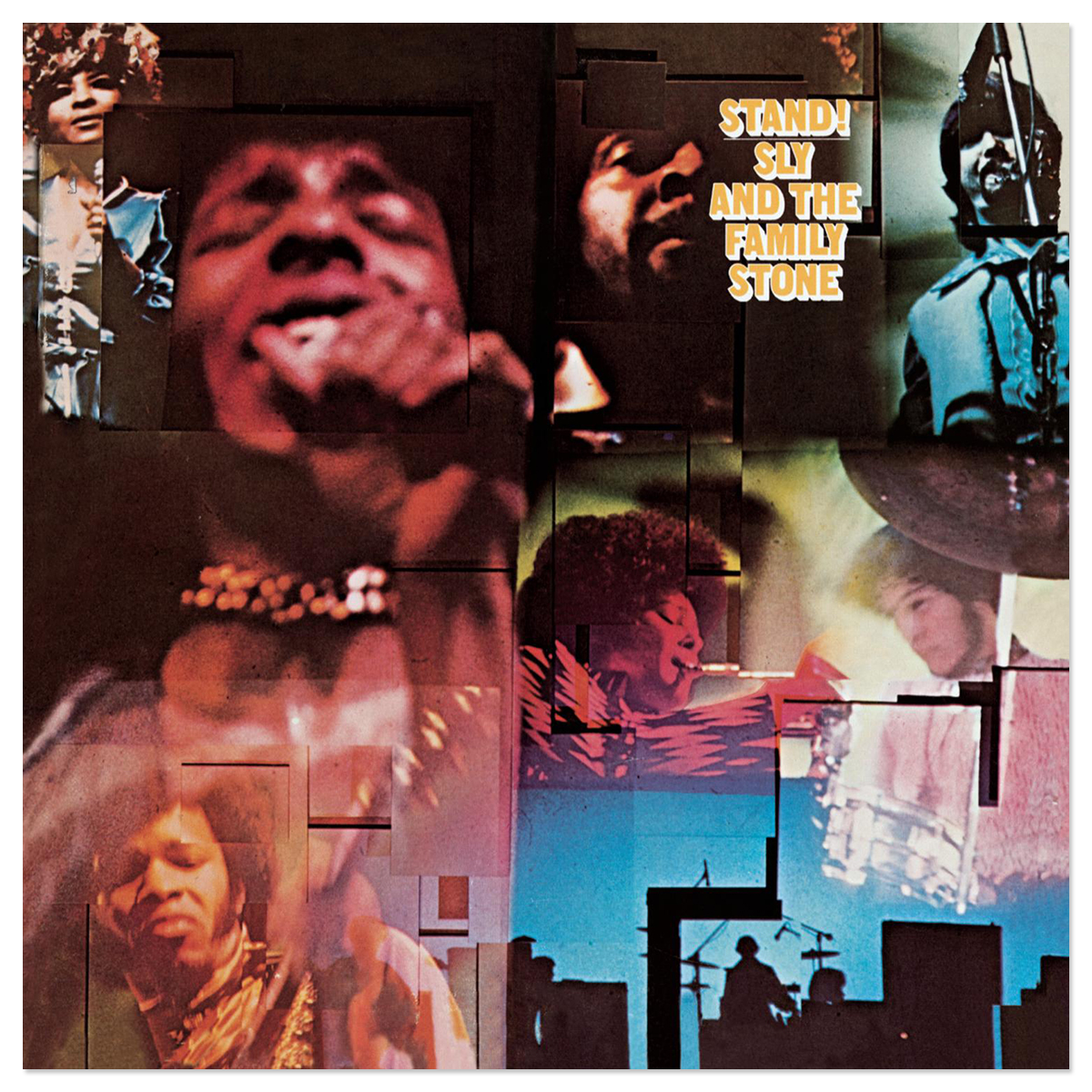

And yet the Beatles survived getting all Stigwooded, so maybe the problem's deeper than that. Because you know who was maybe the first person to take the piss out of "Smells Like Teen Spirit"? Kurt Cobain, when he went on Top Of The Pops in '91 and sang it like a stoned Ian Curtis while doing the least-convincing mime-guitar recorded on video. Nirvana's reaction to fame has been well-documented to a fault; few acts this side of, say, Sly And The Family Stone or Scott Walker have as visibly retreated from everything that made them popular. And with that push-and-pull between Anthem Of A Generation and Burden On The Creator, "Smells Like Teen Spirit" has the bad luck of representing an entire movement and moment in time that many of the people who experience it look back on with regret. Don't get me wrong: there are plenty of legitimately reverent or otherwise reasonably sincere covers of "Smells Like Teen Spirit." Tori Amos' haunted solo piano rendition from her 1992 Crucify EP, Patti Smith's roots-noir beat poetry expansion from 2007's Twelve, and this live rendition by song-title inspiration Kathleen Hanna in 2010 all fit that role amazingly. And there are still plenty of people who find something to deeply identify with in the big hits of the grunge era, "Smells Like Teen Spirit" included. They just have a lot of competition from the artists who found something more absurd to take away from it.

"Weird Al" Yankovic (1992)

There's an endearing, well-traveled story behind this one: After trying for months to get ahold of Nirvana to get permission from the band to record a parody of "Smells Like Teen Spirit," "Weird Al" Yankovic eventually managed to get ahold of Kurt Cobain during their time on the Saturday Night Live set, and Cobain's initial reaction was to ask Yankovic if the song would be about food. Kurt knew his stuff -- it's fun to think of a teenage Cobain slogging through Aberdeen finding comedic solace in "I Love Rocky Road" and "My Bologna" -- but so did Al, whose ear often extended to new wave and college rock through direct parody ("Spam," a takeoff of R.E.M.'s "Stand"), style pastiche (Oingo Boingo homage "You Make Me"), or polka medleys (1984's "Polkas On 45" tackled Devo, the Clash, and Talking Heads). So there's some genuine affection in his decision to make "Smells Like Nirvana" a song about how incoherent the lyrics to "Smells Like Teen Spirit" actually are -- more affection, at least, than metacommentaries like the George Harrison goof "(This Song's Just) Six Words Long" or the absolutely vicious deep cut "It's Still Billy Joel To Me." It helps that Weird Al pushed his band to replicate the original's sound as faithfully as possible, to the point where bassist Steve Jay made a point to recreate Krist Novoselic's finger-dragging in his riff -- though it still feels just a bit quicker-paced, and a full minute shorter. (More background to the making of the song can be found in this 2012 oral history from SPIN -- including the band's initial attempts to figure out what to do with the song in their setlist after Cobain committed suicide.)

Pansy Division (1995)

The pop-punk cover: When it's at its worst, it's a have-your-cake-and-eat-shit exercise in semi-nostalgic, half-ironic distancing from somebody else's popularity. When it's at its best, it's a tribute to the power of reclamation -- or, in the case of Pansy Division, a chance to stand your ground. Queercore pioneers who toured with Green Day during the latter's Dookie-fueled breakthrough, the Bay Area band found a prominent niche at a time when being gay was still largely treated as a cheap punchline by mainstream pop culture. Pansy Division capitalized on their increasing renown by stocking their '95 album Pile Up with covers of Hüsker Dü ("The Biggest Lie"), the Velvet Underground (a genderswapped "Femme Fatale"), and Ned Sublette ("Cowboys Are Frequently, Secretly Fond Of Each Other") as both blatant and winking nods to gay culture, but closer "Smells Like Queer Spirit" is the real coup, simultaneously filthy ("Roll it on now, lubricate us/ Get us off now, ejaculate us"), funny ("Play Fugazi, play Repeater/ River Phoenix wearing speedos"), defiant ("forget the closet, never mind"), and righteous -- they found the perfect way to improve that "a denial" coda by changing it to "no denial" and throwing in a "Jesse Helms on trial" for good measure. Cobain, always an enemy of straight-bro macho bullshit, was said to have loved it when he first heard an early version.

The Moog Cookbook (1996)

Back in the mid '90s, ex-Jellyfish/then-Imperial Drag keyboard player Roger Joseph Manning, Jr. joined up with producer/engineer/vintage-synth collector Brian Kehew for a preposterous yet very '90s concept album. The idea: What if those Switched On-inspired synthesizer albums of the late '60s and early '70s -- records where the likes of Dick Hyman and Gershon Kingsley did primitive electronic versions of James Brown and Beatles songs -- were updated for the alt-rock era? While both Kehew and Manning admitted they were more or less using their instruments in unintended ways -- one electronic music professor at Berkeley made an example of their first record by highlighting it as how you don't play the synth -- they also recognized how faithful that rule-bending was, what with the original Moog pioneers drawing a lot of their most distinctive sounds off happy mistakes and accidental tweaks. That blend of goofy-yet-cool science-music made for the perfect kind of pisstake circa 1996, when the angry-young-man yarl of post-grunge "active rock" started feeling stale. And since Beck, Air, and Stereolab were back to making those old vintage-synth sounds trendy again, hearing a similar (if more irreverent) treatment given to the likes of "Basket Case" and "Black Hole Sun" was as big a zeitgeist-tweaking revelation as you could expect from what's essentially a comedy record. Their "Teen Spirit" is a highlight because it's also a genre-warping exercise: It is surprisingly natural to transform that riff from a Pixies-via-Boston (the band) churn to a funk bounce worthy of Billy Preston or Junie Morrison. Dave Grohl dug it so much he asked the Moog Cookbook to compose a version of the Foo Fighters' "Big Me" for an elevator-music cameo appearance in their video for "Monkey Wrench."

Melvins (2000)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=ZA8H_Mnfilw

The relationship between Kurt Cobain and the Melvins was a deep but often painful one. The Melvins were one of the catalysts for Nirvana existing in the first place: They were former bandmates in Cobain's pre-Nirvana band Fecal Matter, and after the recording of Bleach Melvins frontman Buzz Osborne was the one who introduced Cobain and Novoselic to Grohl. (Melvins member Dale Crover was one of two pre-Grohl drummers for Nirvana alongside Chad Channing.) But by the end of Cobain's life, Buzzo was torn up by the toll that Cobain's drug abuse was taking on his friend, a problem that was already debilitating by the time Cobain was brought in to produce the Melvins' Houdini and was subsequently fired for spending most of the sessions passed out. In the Jan/Feb 2011 issue of Revolver, Osborne remarked that "I was there at the very last show Nirvana played, which was the last time I saw him. He wasn't happy... at that last show, I told him to leave, get out, run. He needed to get off drugs. If he wasn't on drugs, none of that would've happened. Kurt, he could've had a future, he could've turned his life around, and he would've been a wonderful person. It wouldn't have been easy, but he could have done it. I would've preferred that. That or no success whatsoever. I would be far happier if he had never had one iota of success and was alive." Maybe that's why their "Smells Like Teen Spirit," perversely positioned as the leadoff cut of their 2000 album The Crybaby, has that sardonic air about it: It's a nearly note-perfect recreation of the sound and the energy and the whole vibe of the original, and who do they bring in to do lead vocals? Fallen '70s kitsch teen idol Leif Garrett. There are few ways more direct than this to damn Kurt gaining fame at the cost of his life.

Dsico (2001)

Oh boy. Electroclash! Australian electro/synthpop/mash-up artist Dsico (aka "Dscio That No-Talent Hack") rode a brief wave of poptimist all-the-rules-have-changed mania at the beginning of the millennium that didn't last nearly as long as the spotlight moments afforded the likes of, say, Soulwax. It's not clear why, other than maybe the fact that giving your albums titles like I'm Not Retarded and Punk As Pussy EP might be some kind of hurdle vis a vis legacy-building. His Rate Your Music and AllMusic entries are incomplete ghost pages, and even his deliberate-typo alias is too easily thwarted by the fact that looking him up on YouTube is going to dredge up as many misspelled Italo videos as it does actual Dsico tracks. "Smells Like Electro" still remains his most well-known track, and it's a pretty solid stab at creating something that sounds less like a goof and more like a what-if that swaps out Aberdeen for Detroit and/or Berlin. It's at least more effective than his efforts to do the same to the Donnas and the Ramones, and more reverent than his Kid606-ish breakcore deconstructions of Justin Timberlake and Missy Elliott. (TRIVIA TIME: Aside from Dscio's releases, the only albums to come out under the label Spasticated Records Australia are an electro AC/DC tribute album called Watch Me Explode, a comp called Ministry of Shit that features the briefly viral/eternally ridiculous "Ice Ice Bacon," and some pressings of Unstoppable, the album Girl Talk released before Night Ripper went massive.)

Los Straitjackets (2009)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=egxGgmlywrM

Nashville's Los Straitjackets first came about in the tongue-in-cheek early-mid '90s, which might be one reason why their lucha-masked instrumental surf-abilly antics were typically seen as cool retro cross-cultural style for the Conan O'Brien crowd rather than blatant cultural appropriation. Despite their affinity for Mex-American and other Latin rock music, none of the band members are actually Latino, which could arguably make them the El Generico of garage bands. But as tributes go, they're legit -- their version of Rock en Espanol has a deep sonic connection to '60s Chicano rock bands like Thee Midniters and ? And The Mysterians. So they're curators of a style that still seems a bit underrepresented in mainstream music, both as a historic throwback and a more contemporary border-crossing sound, and they've managed to translate that into a following that's actually big enough to fill 50,000-seat arenas in Mexico City. I admit this is a lot of lead-in just to say that their "Teen Spirit," released in 2009 as a split 7" with Southern Culture On The Skids' version of "Come As You Are" (slyly paired with Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd classic "Lucifer Sam"), sounds like a total worldbeater when it revives the spirit of ""Whittier Blvd."

Richard Cheese (2009)

You don't have to be a Marxist to subscribe to Karl's famous Eighteenth Brumaire Of Louis Napoleon quote that history repeats itself "first as tragedy, then as farce." You just have to be aware of when irony echoes sincerity, which itself often winds up echoing irony to only a slightly lesser extent. It's probably exaggerating to call Paul Anka's swingin' version of "Smells Like Teen Spirit" a tragedy -- it came out in 2005, a full eight years after Pat Boone's loathsome artifact In A Metal Mood: No More Mr. Nice Guy, which makes it a familiar version of semi-self-aware camp that's more or less lost its novelty to appall. The farce comes in strong, though: Four years after Anka, the parodic lounge homunculus Richard Cheese, whose entire raison d'etre is to do campy cocktail-bar versions of alt-rock hits, did his own version of "Smells Like Teen Spirit" -- not his first go at Nirvana, since his debut Lounge Against The Machine made a queasy joke out of "Rape Me." The whole conceit of his music, that both lounge singers and modern rockers sound like insincere schmucks when stylistically juxtaposed with each other, does seem like a pretty dire insult sometimes. But you've at least got to give him credit for his intro here, where farce mocks tragedy through a nod to U2 scowling at Charlie Manson.

J*DaVeY (2011)

This cover by Los Angeles neo-soul/future-R&B duo J*DaVeY isn't ironic or comedic or even sarcastic -- but it is irreverent, in that it sands down and glosses up nearly everything about the original song's makeup except the lyrics itself, which singer Jack Davey twists melodically inside-out during the chorus to sound more like some kind of blasphemous pop-shoegaze. It's the kind of stylistic risk that made J*DaVey something of a sensation in the '00s -- by the time their debut album The Beauty In Distortion/The Land Of The Lost was officially released in 2008, they'd rubbed stage and studio elbows with Prince, Phonte, ?uestlove, and a then-largely-unknown bass player named Steve "Thundercat" Bruner. But around the 2011 release of the EP Evil Christian Cop: The Great Mistapes, they'd wound up severing ties with Warner Music Group and had to release the album they'd recorded for WMG on their own iLLaV8r label -- all while future-soul cohorts like Miguel and Janelle Monáe were getting all the attention. From all accounts, their time beholden to the whims of a major burned them out, to the point where they wound up taking an extended hiatus that's only seen intermittent comebacks since. Maybe they were saying something by covering the biggest hit by one of rock's most well-known casualties of industry-fueled fame and warping it to their own form.

The Muppets (2011)

Right, right, I know: They covered Alice Cooper and Blondie on the old Muppet Show back in the day (albeit with actual input from Alice Cooper and Debbie Harry). Still, even after all these other entries, hearing Sam The Eagle, Rowlf, Link Hogthrob, and fucking Beaker do a barbershop-quartet version of "Smells Like Teen Spirit" is such a weird fit from every conceivable angle that its segment in the 2011 Jason Segel/Amy Adams Muppets movie basically hangs a lampshade on the whole thing. They do this by having captive guest star Jack Black actually wail in agony about them "ruining one of the greatest songs of all time," which he sees as a more horrifying prospect than having Sam The Eagle shave him with a straight razor. It's almost cringe comedy to think about in itself, so maybe it's easier to take if you pretend it's a goof at Baz Luhrmann's expense.

Robert Glasper Experiment (2011)

After so many different weird deconstructions of "Smells Like Teen Spirit," it's only fair that we have a somewhat more profound jazz interpretation to close things out -- and we don't even have to go to the Bad Plus well this time (though they did a fine version back in 2003). Robert Glasper's version of the song has become one of the pianist's more well-known tracks, being a standout on his 2011 Black Radio -- a dubbed-out, post-Soulquarian soul jazz transformation that trades blasting immediacy and a quiet-loud-quiet dynamic for a slow build, Cobain's natural introspective murmur and snarling intensity for Casey Benjamin's vocodered meditation, and horizontal full-speed-ahead charging for vertical flight. Once it fully ascends into psychedelic spiritual-jazz digital distortion, only to break the clouds for Lalah Hathaway's wordless euphoria, the song fully, finally registers as something more than just a comment on someone else's work -- it's a whole new way of finding a path through the original song's catharsis.