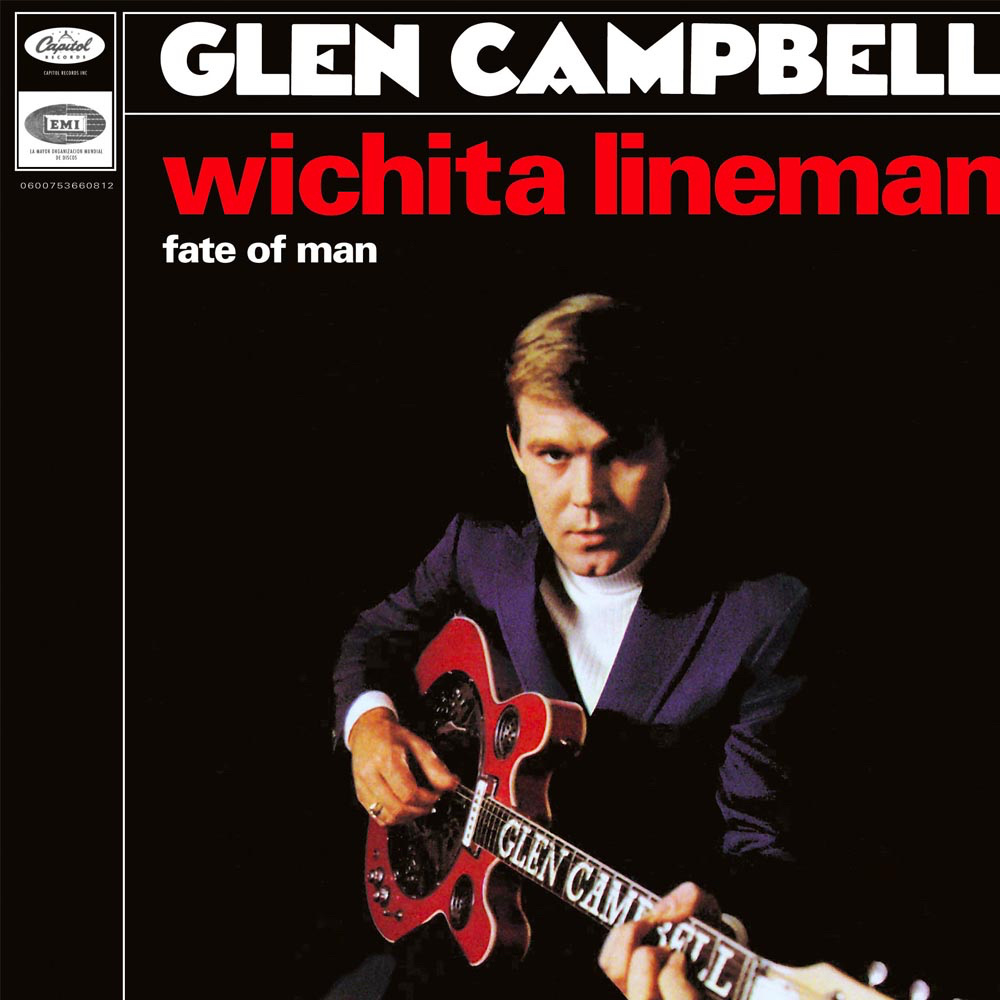

When Glen Campbell passed earlier this month, the first songs that came to mind for people to remember him by tended to vary amidst all the impulsive reactions. Me, I figured hearing him sing the best Brian Wilson song Brian Wilson never sang was how I wanted to memorialize him. Others went for the Wrecking Crew tour de force "Gentle On My Mind," guiltily admitted an affection for the countrypolitan pop of "Rhinestone Cowboy," or waxed nostalgic for his version of Allen Toussaint's "Southern Nights." But three songs written by Jimmy Webb wound up at the forefront, all released within a couple years of each other: "By The Time I Get To Phoenix," "Galveston," and maybe the most iconic pairing of the songwriter and singer, "Wichita Lineman." The title cut to a country-pop album that also had room for interpretations of Otis Redding ("(Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay"), the Bee Gees ("Words"), and Tim Hardin ("Reason To Believe"), "Wichita Lineman" itself became a major phenomenon that reached far outside the boundaries of country radio to nearly every other corner of popular music -- at least for a while, where it must have felt inescapable between 1968 and 1971 or so.

The funny thing is, it's a fairly esoteric notion for a song: Webb was inspired during a long drive in the country, watching the telephone poles stretch off into the horizon with a solitary worker perched on top of one out of hundreds. It's a striking picture built around a relatively uncommon and under-romanticized job, and hinges on some specifics of the technology's peculiarities -- "searchin' in the sun for another overload"; "I hear you singin' in the wire/ I can hear you through the whine" -- with a layered-meaning refrain that evokes a certain loneliness of the long-distance caller -- still on the line, one way or another. Campbell's performance was damn near close to singular, but when a song got popular enough in the late '60s, there wasn't stopping anyone in any genre from giving it a shot, and this is where Webb's songwriting versatility really shone through.

Freddie Hubbard (1969)

Soul jazz -- the crossover between post-bop and popular, typically R&B-derived music -- was really hitting its mainstream stride in the late '60s, so it might be considered something of a late-blooming "ah, might as well" for an artist to christen a circa-'69 album with the title A Soul Experiment. But for Freddie Hubbard, it's understandable that he'd want to frame it as a detour. At the beginning of the decade, trumpet player Hubbard had led some classic Blue Note sessions that resulted in essential hard bop LPs like Open Sesame, Hub Cap, Hub-Tones, and Ready For Freddie -- and been a sideman in even more spectacular examples of the form, like Oliver Nelson's The Blues And The Abstract Truth, Herbie Hancock's Empyrean Isles, and Wayne Shorter's Speak No Evil. At the same time, he was open to appearing on more avant-garde mutations of jazz -- including the unbeatable three-fer flag-plantings of Eric Dolphy's Out To Lunch!, Ornette Coleman's Free Jazz, and John Coltrane's Ascension. Then he went to Atlantic for a stint in the late '60s, and all of a sudden "experiment" meant "do some three-minute pop-style numbers to lure in the Herbie Mann consumer." Fortunately, that can provide its own amazing little side things, and with the right personnel (including drummer Bernard "Pretty" Purdie and guitarist Eric Gale) even this crossover grab spurred some transcendent moments, like this "Wichita Lineman" that finds an opportunity to stretch out on an already ubiquitous standard of the time. Get a load of that overdubbed, multi-tracked solo around where the second verse would be if this wasn't an instrumental -- it's not exactly free jazz, but it still sounds freeing. Shortly after this, Hubbard went to CTI and released Red Clay, an all-time classic of early fusion, so all's well that ends well.

The Electronic Concept Orchestra (1969)

I hinted at this phenomenon when I wrote about the Moog Cookbook in the "Smells Like Teen Spirit" edition of Gotcha Covered, but it really is one of the more underrated aspects of the late-'60s pop music boom that you could get countless albums recorded under the premise of people figuring out how all these newfangled synthesizers worked. We're landing on the moon now! Time to make some Moon Music. Most of these albums sound like a bewildering cross between easy-listening records and tech demos -- a way of marketing that seems hilariously out-of-step with everything else music fans cherish about the era -- and despite more adventurous exceptions like Wendy Carlos or the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, it's easy to hear why "synthpop" didn't catch on as a genre until the late '70s. The Electronic Concept Orchestra had a short, three-album stint in 1969-1970 releasing albums of pop hits and soundtrack selections all Mooged up, and even the kitsch potential of these records is dampened by the fact that it's not even all-synth arrangements, but a Moog accompanied by a studio group. (That this studio group included session wiz guitarist Phil Upchurch is an interesting aside; it must have been a hell of a pendulum swing for him to go from Muddy Waters to this to Curtis Mayfield.) This "Wichita Lineman" comes from an album called Electric Love, subtitled Musical Love-Dreams For Moog Synthesizer, and between that and the boobs-and-lasers cover I'm wondering if the record company expected this to be some kind of sexual-activity soundtrack. (I mean, "Je t'aime... moi non plus" is on there, too, in case you ever wondered what it'd sound like to unleash the Robo-Birkin.) Somehow being subjected to both primitive synth and a half-hearted string section doesn't drain every last bit of pathos from the song, but it does less to inspire some kind of lost-love longing and more to spur thoughts of whether it's ironic that a song that pivots on the odd musical "singing in the wire" qualities of technology isn't all that well served by it... at least, not yet.

The Meters (1970)

There's no such thing as an unlikely crossover where Jimmy Webb's peak material is concerned -- not since Isaac Hayes' widescreen-epic take on "By The Time I Get To Phoenix" became a masterpiece of soul in 1969, at least. "Wichita Lineman" is no exception, and R&B artists covered it en masse between '69 and '71: the upbeat, bassy smoothness of O.C. Smith, a baroque countrypolitan-laced King Curtis sax instrumental, a Motown reassembly sung spectacularly by Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, a velvety and libidinous Willie Hutch version, and Kool & The Gang doing a meditative floating-in-space rendition to a a reception of intermittent intensely appreciative screams on Live At The Sex Machine being just a few examples. But the Meters' 1970 version from Struttin' tops them all, and for reasons that diverged from their previous chart-hitting examples like "Cissy Strut" and "Look-Ka Py Py": Rather than a funk instrumental that hinged on building a groove and sinking unfathomably deep inside it, it's a showcase for keyboardist/frontman Art Neville that presaged the more vocally driven songs they'd notch during Rejuvenation and Fire On The Bayou, their must-have pair of albums in the mid '70s. Neville's voice is an early revelation here, and Leo Nocentelli treats that famous opening riff as the ignition for one of the most nuanced, intricate guitar performances in the band's whole catalog. It's still "Wichita Lineman," so there are limits to how funky you can make it, even if Ziggy Modeliste is your drummer -- but it definitely feels like a dose of raw soul.

Dennis Brown (1972)

Bob Marley's favorite singer and one of the most haunting evocations ever brought up by John Darnielle, Dennis Brown is one of those artists held close to the heart of anyone who thinks about reggae in more than just the entry-level "I heard The Harder They Come a couple times" sense. Brown's version of "Wichita Lineman," most easily heard on the early compilation Super Reggae & Soul Hits, captures the Marvin Gaye of reggae on the upswing, right about the same time "Money In My Pocket" first made him a sensation in the UK. And there's no mistaking his stardom here -- it's sung like he's had a few years to study Webb's melodies and lyrics from every angle and picked out literally each syllable, note, and ad-lib for the most possible emotional devastation, with virtuosity and pure feeling merging into some kind of pop-song singularity that many artists can't even pull off in their own material, much less somebody else's. That delivery of "still on the line" -- dang. Just... dang. (Double dang when the backup singers do the call-and-response in the fade-to-dub outro.)

British Electric Foundation (1982)

So, that Electric Concept Orchestra version up there? Imagine it played a little straighter, in the midst of a pop era that was normalizing yet still finding some measure of exoticism in synthesized music, and delivered with a certain amount of feeling with a lead singer playing things halfway between nostalgic and futurist. B.E.F. were basically Heaven 17 before Heaven 17 existed, with singer Glenn Gregory joining keyboardists Martyn Ware and Ian Craig Marsh shortly after their Radiophonic-gone-nutso releases Music For Listening To/Music For Stowaways. And while most of B.E.F.'s covers-album Music Of Quality And Distinction Volume One featured outside guest vocalists -- kicking off with a Tina Turner-led version of Whitfield/Strong's "Ball Of Confusion" that hinted at her oncoming Private Dancer-driven comeback -- Gregory took lead for a couple, including this "Wichita Lineman" that gives it the full synth-immersion treatment that circa-1969 tech hadn't been up to. It sounds a lot icier, per both the tech and the times -- given Heaven 17's track record, it can easily be heard as Music For Labourers, the lineman toiling under an uncertain tomorrow just a year after "(We Don't Need This) Fascist Groove Thang" got them booted from the BBC for shit-talking Reagan. If that interpretation foregrounds the work as much as it does the romantic longing, the sound makes the technology resonate nearly as foreboding as it is connective -- the mournful, working-class side of synthpop that MTV day-glo histories tend to leave in the background.

Urge Overkill (1987)

Imagine if the Strokes weren't as privileged, pissed off nearly everyone they crossed, burned out far faster and brighter, and were best known for a cover song on a soundtrack assembled by a pop icon who'd maintain a higher level of fame than they would for far longer -- you might be at least a bit on the way to getting just how weird and contentious the whole Urge Overkill phenomenon was at its peak. Forged in the midst of a Chicago scene that found itself giddy to tear them down once they jumped from Touch & Go to the majors, they were, and still are, infamously loathed by frontman Nash Kato's former roommate/producer Steve Albini and encouraged the longest-running anti-fandom Chicagoland had seen since Steve Dahl decided to go to war against disco. So it's pretty much impossible for anyone who remembers that point in history (DISCLAIMER: God help me, I turn 40 next month) to go back and listen to them with an untainted perspective. Is this early dirtbag take on "Wichita Lineman," like their later Neil Diamond cover "Girl, You'll Be a Woman Soon" of Pulp Fiction renown, too laden with the spectre of proto-hipster retro affectations and a desperate need to be rock stars to enjoy without cringing at least a little? Maybe. It really kind of does sound like the sort of band you'd imagine feeling semi-affectionate about the song they're covering but afraid to show it without making their guitars, like, totally fuckin' loud dude -- though it does have the novelty of sounding a lot more like grunge-goldrush 1992 than it does noise-rawk 1987.

R.E.M. (1995/96)

Sometimes all you need to say is "Here is what 'Wichita Lineman' sounds like as performed by R.E.M." and what you imagine will be exactly what you get. I don't say this to diminish them so much as I say it to point out how distinct they'd become by the mid '90s -- distinct enough, maybe, that any attempts to deviate from it were felt pretty deeply no matter how good those diversions were. (Not to get all True '90s Kid on y'all, but it is a very clear memory among record shoppers that one could always find copious copies of Monster in the used CD bins starting sometime in about early '95.) This "Wichita" was the B-side of New Adventures In Hi-Fi single "Bittersweet Me," itself part of a record that did as much as it could to reconnect with R.E.M.'s old IRS years while still reeling from the moves of Monster, and it fits in well with the band's general feeling of rootless, constantly travelling borderline burnout en route to drummer Bill Berry leaving the band. Wrap all those notions up in this performance, and the inclusion of the song in their live setlist (this recording was taken from the Houston stop of their '95 Monster tour) takes on some real weight.

Justus Köhncke (1999)

Hey, looks like we hit the electronic-reinterpretation trifecta: primitive Moog, synthpop, and now, house music. In the case of German producer/singer Justus Köhncke, the house in question is of the minimal variety, the type of which really started to emerge at about the same time Köhncke released his all-covers Spiralen Der Erinnerung. (By the time he released his next solo album, 2002's Was Ist Musik, he'd found a more-or-less permanent home in foundational Cologne microhouse label Kompakt.) So maybe this is a funny little culmination of this through-line, an ultra-minimalist version that sounds so beholden to the most sonically reduced and hushed iteration of electronic music that it only takes the slightest human touch to make the heart of the song jump out. Köhncke's damn near closer to talking than singing here, and closer to whispering than both, but even if that seems kind of fussy at first it makes for a strong base to build off when he actually pushes that voice on that first "still on the line." That synth-guitar in the middle sounds pretty cheeseball, though.

Johnny Cash (2002)

Johnny Cash is rightfully revered as a musician and an icon and the representative of something approaching outlaw culture, but let's not all go about reducing him -- even in his Rubin-collab later years -- solely to "Hurt" and that photo of him flipping off the camera. He was also fantastic when he was comedic or maudlin or 100% Woody Guthrie-mode sincere or just plain folks, and you'd best believe that when the man most younger generations picture as a grizzled old badass actually puts his aged voice through the Jimmy Webb wringer he chisels a masterpiece out of solid granite using nothing but a feather.