I don't believe in superstition, but here I am, a writer with a cover-songs column, discovering on Friday, April 13 that Taylor Swift did a countrified version of Earth, Wind & Fire's "September." Well, shit. Might as well take a swim in Crystal Lake here and see what's going on.

I'm not enough of a genre purist to instinctively cringe at the idea of a country version of EWF's most enduring classic. Just picking candidates from the fairly wide category "country and country-adjacent white women singers," I could go for the idea of anyone from Neko Case to Brandy Clark taking it on -- you know, somebody with some actual vocal range and the ability to inhabit a personality besides her own tabloid reflection. And I'm not excessively reverent of the song that I can't laugh my ass off at somebody tweaking it, so long as the tweak is good-natured enough. But whew: Swift drained all the joy out of one of the most euphoric songs of the '70s and didn't do enough with the resulting dissonance between lyrics and music (verse: "never was a cloudy day"; music: Seattle in February) to shake that overarching sense of wrongness from it.

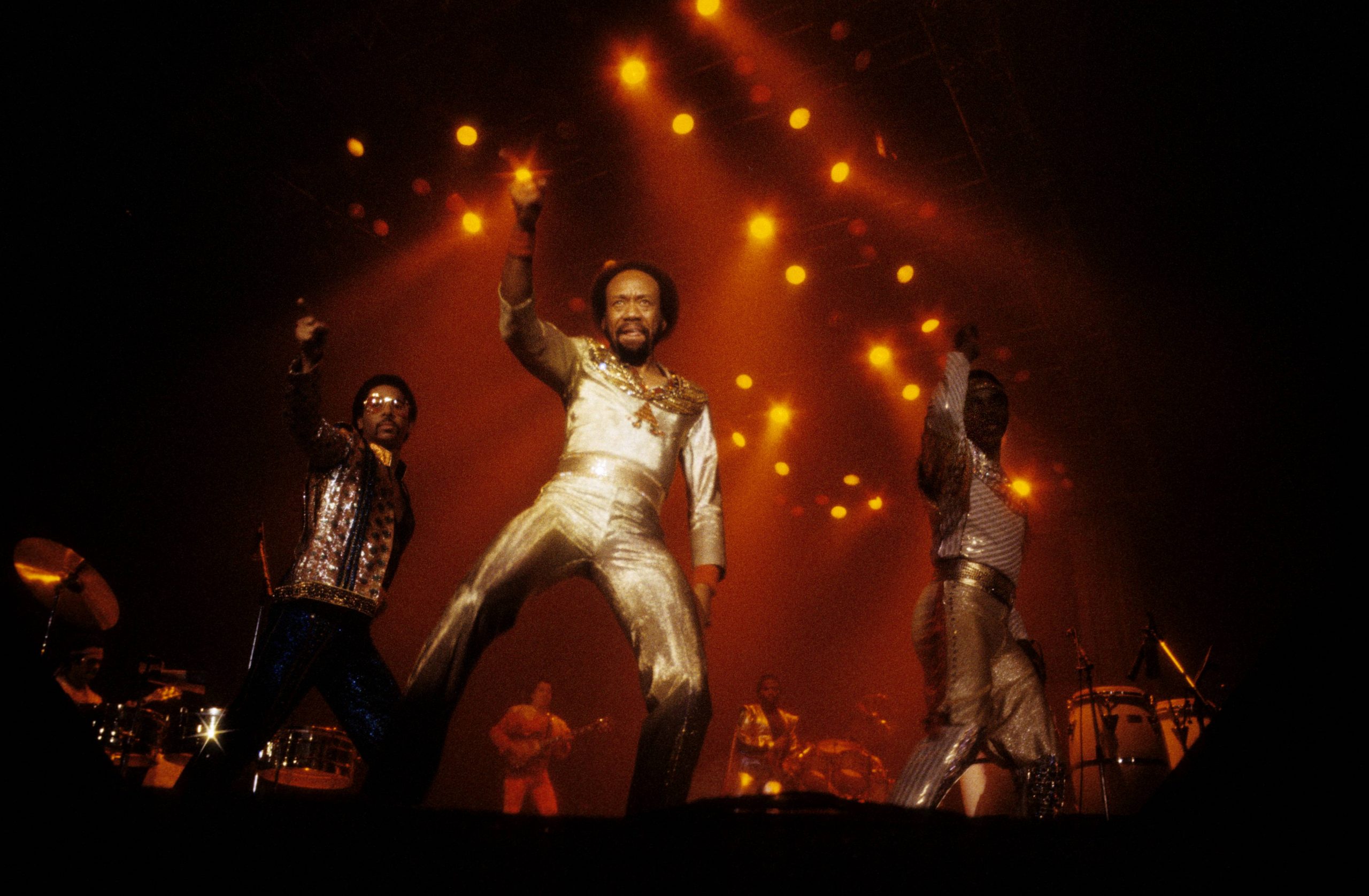

So what does it sound like when an Earth, Wind & Fire cover works, then? Well, considering all the different varieties of R&B they mastered throughout the '70s and early '80s, they leave interpreters a lot of room to work. The band's repertoire includes everything from dynamic soul-jazz to no-nonsense funk grooves to disco jams to roller-boogie anthems, their musical diaspora is tinged with the sounds of Afropop, Latin soul, and MPB (música popular brasileira), and few peers have balanced out introspection and extroversion quite like them, from ballads to dancefloor fillers.

They're not easy to live up to, but those that come close find themselves invigorated just by capturing a portion of that vibrancy. Here are eight examples of artists who picked up what Maurice White and his legendary ensemble were laying down.

Joe Cruz & The Cruzettes, "Help Somebody" (1972)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=2qtTVkEodTY

How soon somebody puts out a cover version of one of your songs isn't necessarily the most accurate metric to use if you want to figure out how long it takes for your band to get recognized. But it can at least be a bit of fun trivia, and a close-enough glimpse at just how much cultural influence a band's starting to spread. By the end of 1971, Earth, Wind & Fire had already put out a modestly successful self-titled debut on Warner Bros., released a comparably popular follow-up in The Need of Love, and performed the Melvin Van Peebles-written score to the blaxploitation-defining cult hit Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song, so having one of their early singles covered shouldn't be a huge surprise. It's just that the first band to be on record covering what would become one of the most popular R&B acts of the decade was... the house band at Manila's Hyatt-Regency Hotel.

Joe Cruz & the Cruzettes put out a number of cover-laden LPs in the '70s, including 1973's At The Hyatt Regency Hotel -- and if you want to get an idea of what a band like that might be compelled to perform for a tourist-dollars audience, just know that they recorded both "Theme From Shaft" and "Horse With No Name." So what they lacked in identity, they made up for in versatility -- though they could tighten up and focus on a solid Latin funk sound when they wanted to. The self-titled LP they put out in 1972 is a bit more focused on that, with a handful of Malo covers and a version of Santana's "No One To Depend On," but their take on early EWF single "Help Somebody" fits that bill, too, foregrounding the original version's undertones of classic late-'60s boogaloo. Shame the Up With People harmonies don't quite do the original's vocals justice.

Ramsey Lewis, "That's The Way Of The World" (1975)

Roy Ayers Ubiquity, "The Way Of The World" (1975)

After some personnel changes and the crucial addition of singer Philip Bailey, Earth, Wind & Fire's ascent from reasonably popular R&B band to best-selling trendsetters had become impossible to ignore by 1974: That year's Open Our Eyes went platinum, its single "Mighty Mighty" became their third top 40 hit, and they earned a slot playing the massive California Jam festival to a crowd of over 300,000 paid attendees. But one notable collaboration that year would embody a major development in Black pop music: Maurice White, who played drums full-time with the Ramsey Lewis Trio for three years and nine albums from 1966 to 1969, was invited back to the studio by Lewis for the recording sessions for the album Sun Goddess. Members of Earth, Wind & Fire joined them -- White co-wrote the title cut and "Hot Dawgit," both of which featured Bailey on vocals -- and the ensuing album crossed over big time, hitting the top 10 in singles and album charts all across the board from jazz to disco to soul to pop. There are too many candidates to choose from if you want to define the most pivotal or successful album that brought jazz-funk to the masses, but there are few on the level of Sun Goddess when it comes to pleasing as many niches as possible.

Within a year, Super Fly producer Sig Shore recruited EWF to both soundtrack and appear in the underrated Harvey Keitel record industry drama That's The Way Of The World, which is maybe the most extreme case ever of a smash album eclipsing the success of the flop movie it soundtracked, in that most people completely forgot that it was a soundtrack in the first place. (Not that the record didn't provide more memorable contributions to motion picture soundtracks later on.) And with the band's longstanding soul-jazz bonafides and ability to cross over on their own terms -- That's The Way Of The World made #1 pop and R&B albums en route to going double platinum -- they made for fine inspiration for both their previous collaborators and one of his most successful peers.

The Ramsey Lewis version of "That's The Way Of The World" is solid enough, building off the easy-tempo euphoria and cleverly concealed undertones of sadness from the original and giving Lewis a lot of space to lay out some lively improvisations on electric piano -- though the presence of the song's original co-writer Charles Stepney on production and additional synthesizer did much to ground it in the spirit of the song as it was written, even if it was redone as a chorus-only mostly-instrumental. The same year, vibraphone don Roy Ayers led his own take on the song, cutting out the vocals and the "That's" but adding in a lot more: His own instrument rings its way through an expansion of the song's vocal melody that nails a paradoxically mellow intensity -- relaxed and invigorated all at once.

The Salsoul Orchestra, "Getaway" (1977)

There were R&B bands that "went disco," and then there were R&B bands that created disco. EWF had a hand in it, but they did so on their own terms, a headier and funkier side of the sound that charged where other proto-disco greats like Barry White and Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes soared. They didn't even really need to prove themselves for the dancefloor, they were just ready for it, and few songs hinted at that inevitability better than the 1976 album Spirit's leadoff cut "Getaway." It's not just in the impeccable way those horns, the choir, and that punchy backbeat all make that low-end groove sound impossibly high up in the stars -- it's in the urgency of it all, dance as liberation, a call to find a place where you can finally really move: So come, take me by the hand/ We'll leave this troubled land.

Disco's original vibe was of a communal escape through dance, whether you were a societal outsider searching for a community or just a working stiff looking for one night of freedom, and the right bands picked up on that vibe to perfection. The Salsoul Orchestra were one of those bands, and even if their output could be uneven -- their '77 LP Magic Journey includes both the transcendent Loleatta Holloway-sung anthem "Runaway" and a cringeworthy version of the Royal Teens' novelty oldie "Short Shorts" -- their best cuts were almost diabolically joyous. All they really had to do for "Getaway" was make the Latin flourishes in the original version's rhythm big enough to make the New York clubs tremble, and compensate for the lack of vocals with a host of amazing horn solos that rivaled the likes of Fred Wesley and Maceo Parker. Master arranger Vincent Montana Jr., the man who helped make all the great early-'70s Philadelphia International orchestral sections sound godlike, would do the rest.

Seventh Extension, "Reasons" (1979)

If they ever make a 20 Feet From Stardom for reggae, Derrick Lara belongs in it: As a member of the Tamlins, he's sung backup vocals on albums by Peter Tosh, Sly Dunbar, Dennis Brown, Big Youth, Jimmy Cliff, and just about every other singer from the '70s and early '80s who figured in the answer to the question "If I like Bob Marley, who else would you recommend?" The Tamlins as their own thing had modest success for their 1980 cover of Randy Newman's "Baltimore," produced by Sly And Robbie as inspired by Nina Simone's 1978 reggae interpretation, but as album artists their lovers' rock-heavy releases were largely slept on.

Derrick Lara's solo work is its own thing, though. At roughly the same time the Tamlins were cutting underrated singles, Lara was putting in work on some of the best reggae covers of American funk, disco, and R&B standards going: His versions of Off The Wall-era Michael Jackson classics "Rock With You" and "Don't Stop 'Til You Get Enough" reveal a spectacular, emotive falsetto, and hearing him glide through Smokey Robinson's "I Second That Emotion" is a pleasure. His version of EWF's "Reasons" might be the best showcase of that voice -- every bit a match for Philip Bailey's in virtuosity and feeling. And it's a trip to hear little-known studio band Seventh Extension put some skank into an already slinky composition.

112, "After The Love Has Gone" (1998)

It's not just nostalgia that makes R&B from the '70s feel a bit more enduring than a great deal of the stuff that came out of the '90s -- through hip-hop, whether it's RZA chopping through the atmosphere of classic Memphis soul or Dr. Dre building a whole new epoch of g-funk out of Parliament and Ohio Players, '70s R&B largely defined the '90s. Of course, it was in a form that built off decades of DJ-honed transformative techniques and production tricks, but that form required a lot of crate digging and reconnection with the work of previous generations: learning why something had that certain bump to it by isolating the most thoroughly deep portion of that something and just marinating in it.

All this is to suggest, though maybe not definitively declare, that hip-hop actually did more justice to a previous era's R&B than R&B did in the '90s, at least until neo-soul got a foot in the door. Maybe that's what makes 112's take on EWF so jarring: There's nothing inherently wrong with this sort of sleekly produced satin-sheets R&B, especially when there's a strong vocal-quartet sound taking on that stunning chorus -- but oof, the production. This cut from the tribute-filled New York Undercover soundtrack collection A Night At Natalie's is just off enough to sound cheap in comparison to the original, whether it's the not-quite-full-enough keyboard sound or the fact that the drums sound both louder and flatter. Once again, hip-hop did it better (or at least stranger).

J Dilla, "Brazilian Groove (EWF)" (2001)

Speaking of hip-hop producers well-versed in R&B, here's the man who proved to be a secret weapon in the sound of D'Angelo's Voodoo and the best-ever to remix a Janet track (non-Jam/Lewis division).

In 2001 J Dilla was still an aka for the producer then known as Jay Dee, and his album Welcome 2 Detroit was his first effort to establish himself as a genuine auteur in the wake of his classic formative work with his group Slum Village and the production braintrusts the Ummah and Soulquarians. It's an ambitious work where he takes on Kraftwerk-oid electro, '70s Blue Note soul-jazz, deep-rooted Afrobeat, and more than one brush with MPB -- which, funny enough, all convene in his rework of the oft-sampled All 'N All interlude track "Brazilian Rhyme (Beijo)." A tribute of sorts to his A Tribe Called Quest cohorts, who sampled the indelible "ba-dee-ah" vocal for their cut "Mr. Muhammad," Dilla dreamily reproduces that wordless singing and its accompanying fingersnaps through the audio equivalent of a psychedelic liquid light show and swaps out its springy-stepping uptempo disco-funk for something more characteristically loping and fuzzed-out.

Meshell Ndegeocello, "Fantasy" (2007)

Meshell Ndegeocello's Ventriloquism dropped last month to well-deserved acclaim, the latest in a long line of moments where she's become nearly as renowned as a re-interpreter of other artists' works as she is for her own. As an artist and auteur who never met a cover she couldn't transform into its own emotional statement -- from her sly queering of Bill Withers' "Who Is He And What Is He To You" to the ratcheted-up tension of her acid-bath take on Whodini's "Friends."

So here she is on Stax's 2007 compilation Interpretations: Celebrating The Music Of Earth, Wind & Fire, taking one of EWF's most utopian moments and adding just the right undercurrent of reality to "Fantasy": opening it with a Sir Nose/Funky Worm voice intoning that "today's program is sponsored by Every Man For Himself Incorporated, the people who brought you the individual climate control device" and giving some mic time to a dedication for "all my brothers and sisters in Iraq," she then proceeds to turn it into a heat-singed hard-rock jam in the vein of Living Colour and turns all those euphoric melodies inside out until they sound like the kind of thing you whisper to yourself to stave off an anxiety attack.