The smoking ban was a good thing. The first time I walked out of a club without my hair and clothes reeking of smoke, without my eyes stinging, I felt like I was living in a whole different dimension. That had been an ambient, omnipresent part of the live-music experience, and then all of a sudden it wasn't. Venue staff no longer had to function in an environment of pure gaseous smog. Smokers could huddle outside the venue and strike up conversations. But there are consequences that we didn't fully understand at the time, things that we might not fully be able to put into words. After the smoking ban, for instance, I never saw the air flutter around Chan Marshall.

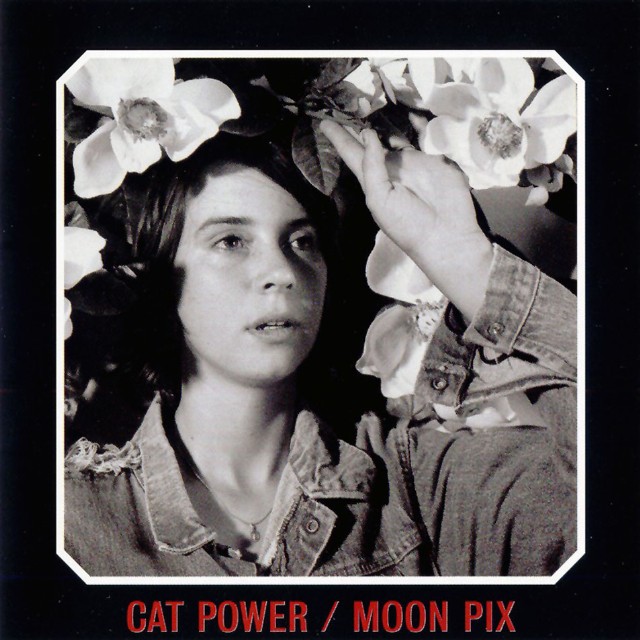

Sometime in 1999, I took the train from Manhattan to Hoboken with my then-girlfriend to see Cat Power, the one-woman project who'd just released an album that had left much of indie America's head ringing. It was a weird vibe that night. Maxwell's, the Hoboken venue, was small and stuffed full of people. And most of the people in that room seemed to be there to showily shout encouraging things at Chan Marshall.

Marshall already had a reputation by then. There were stories about how she'd break down during shows, how she'd run out of venues crying. She was clearly uncomfortable up on that stage, clearly forcing herself to get through it. She'd talk about it, too. That night, she apologized constantly and profusely in between songs: "I'm sorry. I'm sorry. This fucking sucks." One woman in the crowd, maybe trying to lighten the mood, called out to Marshall, "You need pyrotechnics!" (This was before Great White.) "I need Technotronic," Marshall responded, and the crowd nervously tittered, even though Marshall's joke -- I guess it was a joke -- didn't make any sense. (The presence of Technotronic, the late-'80s and early-'90s hip-house group who had a #2 hit with "Pump Up The Jam," would not have improved that Cat Power show.) People would yell, between songs, that they loved Marshall, which just seemed to make her fold inward even more. It was uncomfortable.

But when Marshall sang, the air within the room changed. Everyone stopped talking completely; nobody even whispered to each other. She'd play guitar or piano slowly, plucking a few quiet notes and letting them reverberate. And she'd sing these languid, formless songs -- song that mostly weren't on Moon Pix, if I'm remembering the night right. Maybe I was just tired that night, or maybe I was having that weird physical reaction you get when you have to stand very still in a crowded space while listening to quiet music. But I remember Marshall's features blurring. I remember the light changing. I remember her looking like a ghost. Maybe it was the smoke in the air. Maybe it was something else.

Marshall had always been a bit of an elusive, mysterious figure. She'd grown up in Atlanta and started making music as a social thing, as something to do in between drug experiences. She'd lived in New York and Portland and South Carolina. She'd recorded her first two albums in a single day. Marshall's recording career was young, but she made a lot of music, and that music was dark and spectral and heavy. And then, with Moon Pix, it only became more so.

The story of Moon Pix, the one that Marshall always tells, is that she was living in a South Carolina farmhouse with Bill Callahan, getting ready to leave music behind entirely. But one night, she had a vivid and overwhelming nightmare, a vision of evil spirits trying to get into her house to take her away. She woke up in a blind panic and immediately wrote much of Moon Pix that night. Then she got Matador, her label, to fly her to Australia. She bummed around for a few months and then got together with Mick Turner and Jim White, two members of the tangled-up instrumental rock trio Dirty Three, and recorded the album in a few days.

It's hard to assign concrete meaning to most of Moon Pix, since it's not a concrete album. It's Marshall, languid and expansive but also raw-nerve vulnerable, venting spacily about formless, nameless anxiety. Marshall was young and familiar with what heroin had done to her peer group, so she knew about mortality. And she'd grown up in the church, with all the intense confusions about morality and the afterlife that that brings. And so all of that comes out, in twisted and personal ways, on Moon Pix.

She sings about going to hell over and over. Sometimes, it's almost playful. Sometimes, it's desolate and urgent. She sings about trying to find comfort in God and getting just nothing in return: "Have you ever seen the face? / You know the one I’m talking about / Have you ever been to that place? / You know, the one I’m not supposed to say." She sings "Moonshiner," the old folk traditional, putting herself back into the skin of someone living on the other side of the law, in the earlier days of the dying century: "You're already in hell, you're already in hell / I wish we could go to hell." She sings about rock-scene tedium in mythic terms: "Must be the colors and the kids that keep me alive / Because the music is boring me to death."

The music exists entirely on its own frequency. Turner played guitar in tangled snarls, and White played his drums just off, always bringing a chaotic looseness, so both of them turned out to be ideal sonic partners for Marshall. Marshall had this remarkable voice, this honeyed death-moan, that swallowed everything around it like a voracious blob. Her songs didn't have shape or structure. Oftentimes, she'd trail off in the middle of a line, leaving a thought unfinished. But this sound -- wispy, miserable, convinced of its own damnation -- was its own kind of structure.

Marshall did things on Moon Pix that were new to her, that probably made her stark and feverish music more approachable to dilettantes like me. The drums on the opening track "American Flag" were the drums from the Beastie Boys' "Paul Revere" slowed slightly down. "Moonshiner" drew open parallels to old folk-blues, while echoes of that music reverberated throughout "Metal Heart" or "Colors And The Kids." "Cross Bones Style," the first Cat Power song that I ever heard and maybe still the best, was swirling, pulsating dream-pop with maybe the faintest hint of New Order in its groove.

But for those of us who were new to Cat Power, Moon Pix didn't sound approachable. It sounded dark, obsessive, and beyond heavy. It was an album that, if you heard it at the right time of night and in the right state of mind, could swallow you up completely. Maybe Moon Pix was an influential album; I don't really know. I could certainly imagine plenty of other young women hearing this young woman singing of darkness and demons and hell with such vulnerability and such power, and I can imagine them being inspired to try making music themselves. But I never heard another album like Moon Pix, from Cat Power or anyone else. And in the two decades that have followed, indie rock has largely moved away from trying to capture that sense of the uncanny, of worlds beyond the one we can see.

I've seen Cat Power a lot of times in the years since that night in Hoboken. I've seen her in five cities, on two sides of the Atlantic. I've seen her struggle, and I've seen her overcome those struggles, playing incredible shows. When she was touring behind The Greatest with a full Southern soul band, playing to huge theater crowds and discovering her inner showman, it made for a beautiful night, a glorious story of personal breakthrough. These days, Cat Power is a dependably fun festival act, something I never would've foreseen after that first night. But in all the times I've seen her since then, she's never shimmered. She's never become a ghost.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]