Will Oldham is a slippery interview. He doesn’t love to explain the meaning behind the songs he writes and he has made that known throughout his long career. His wit is dry and intimidating, and when I saw him in conversation at Brooklyn’s Bell House a few months back, I tensed up during the Q&A portion, anxious for anyone who would dare raise their hand to ask a question. Oldham isn’t prickly, exactly, he just comes across as the kind of person who operates on another wavelength and is way more interested in talking about, say, the adverse effect Spotify has had on the music industry than why he wrote one song a decade prior. Oldham has big ideas; he communicates them simply or not at all.

The occasion of the talk was the release of Oldham’s book Songs Of Love And Horror: Collected Lyrics Of Will Oldham. It came out last year in conjunction with an acoustic album by the same name put out by his longtime label Drag City. Each song listed in the book includes an annotation that explains, to a certain extent, what Oldham was thinking about when he wrote it. The annotations are written in blue, and most of them are no more than a sentence long.

It’s curious that an artist like Oldham, who is well-known for not wanting to act as translator, would agree to writing this book. I suspect that it is a result of getting a little bit older, knowing he's played a role in the trajectory of contemporary popular culture, and feeling the need to reckon with his own legacy lest that work be left to someone else. In the book’s introduction, Oldham writes: "If something is too specific, its light burns out quickly. If the words are exceedingly oblique than the light never catches. The lines of a song get put together with the knowledge and hope that those lines will be sung very many times before they’re forgotten and disappear."

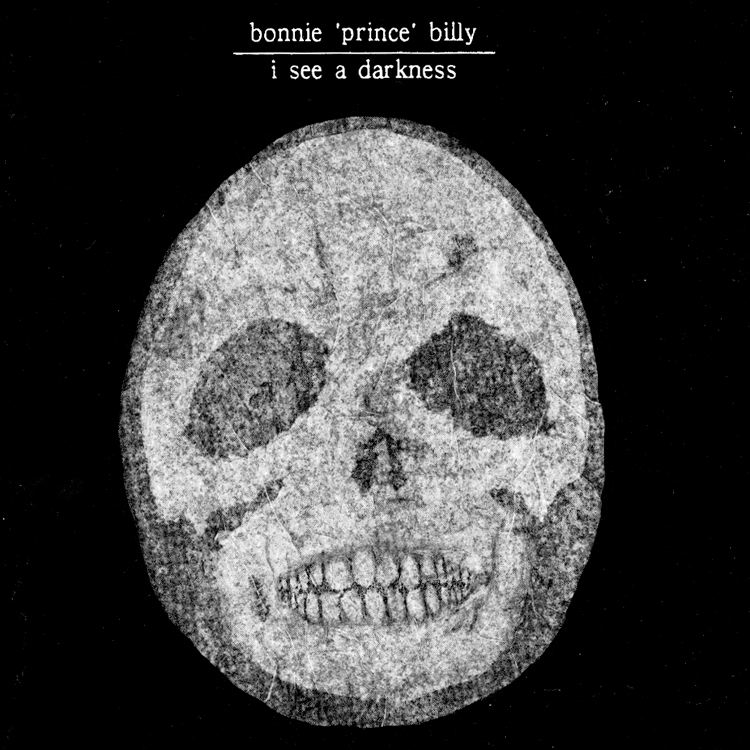

Twenty years ago this weekend, Oldham released his first full-length album under the Bonnie "Prince" Billy moniker after recording for years under various iterations of the Palace name. The LP is called I See A Darkness, and though Oldham has put out dozens of albums in its wake (he is prolific), this remains one of his best-known collections -- probably the best-known. At the time of its release, I See A Darkness was a smashing success by independent-country-ish-Americana-folk-album-put-out-by-Drag-City standards. It was, as Oldham writes of opening track "A Minor Place," a "statement of purpose." It is an album that grapples with ideas that are macabre and overwhelming; Oldham sings about death’s inevitability in a way that is searching and unmistakably human, funny and sad at the same time. So much art attempts to fill space, to mend wounds, to eradicate injustice and make sense of the nonsensical. I See A Darkness does the opposite: It tunnels deeper into the unknown, and it does it with a sense of humor.

The darkness Bonnie "Prince" Billy confronts on this album isn’t even darkness, really. It’s abyss. Some of the songs make me think of Charles and Ray Eames' short film Powers Of Ten, which attempts to illustrate how infinitely vast our universe is and leaves the viewer feeling very small -- a blip on an endless continuum. The song "Death To Everyone" illustrates the same idea. "Every terrible thing is a relief/ Even months on end, buried in grief/ Our easy lifetimes, which have to end/ With the coming of your death friend," Oldham delivers these words as if he were reciting a poem at an especially dour coffee shop open mic. The song transitions easily into the bass-driven, psychedelic "Knockturne," which initially reads as similarly morose, but is really about doing it with a pretty woman. The words "comely" and "cock" emerge, and the song closes with a note of devotion: "Now I truly love you wholly/ No one else could e'er have stole me/ And the world so far below me/ For ye and me it turned."

On paper, Oldham’s writing reads as old-timey, and Bonnie "Prince" Billy’s output has long been lumped into the expansive and oft-debated genre known as "Americana." Tonally, his songs often borrow from Appalachian folk traditions, although rather than growing up in the mountains Oldham was raised in Louisville, where he still resides. When Oldham dons a cowboy hat and adopts the Bonnie "Prince" Billy persona, he shapeshifts into a character, one whose personal life doesn’t necessarily inform the songs he writes. It's for this reason that I See A Darkness feels like it exists somewhere outside of time. It has the quality of of something well-worn and eternal.

Johnny Cash must have recognized that when he heard "I See A Darkness" and decided to record a version of it. The song is among Oldham’s best-known, and it is the one that won’t be forgotten or disappear. While Oldham’s version of "I See A Darkness" is minimalistic and a little frayed, Cash’s cover is blown-out, epic. He recorded the song in 2000, a year after its first release and three years before he died at 71. Cash's cover cemented Bonnie "Prince" Billy’s legacy, and it was lauded as one of the Man In Black’s greatest final offerings. In Cash's hands, it became, for lack of a better term, an existential song, one that confronts the futility of living with unnerving honesty. Oldham might disagree.

In a 2001 interview with Pitchfork, Oldham said that "I See A Darkness" is less about dying and more about an evil person trying to do good in the world and failing time and again. "The death issue is more prevalent when you hear Johnny Cash sing it. But I definitely never thought about the death association with that song."

"Are you afraid of death?" The interviewer asks in a follow-up question.

"For years I was, and this year, I have been a lot. But not today."

Oldham released another version of "I See A Darkness" on Bonnie "Prince" Billy's Now Here's My Plan EP in 2012. It is a radical redesign. No longer haunting, this iteration is an upbeat jaunt. The video follows Oldham as he drinks in bars and dances down city streets, his mustache overgrown and hanging in his mouth. You can spot Angel Olsen, who provides backing vocals on the new version's chorus, in the video, too. It's certainly not the best version, but it is an example of how rearrangement can lend a song new meaning, that sometimes a tonal shift changes everything. The easiest interpretation is not always the correct one.

The battle of good and evil is waged throughout I See A Darkness, most notably on "Today I Was An Evil One," on which Oldham sings the word "humbly" like this: "humboly." In his book, Oldham writes: "Humboly has an extra syllable, so that the word does not slip by un-noticed." On "Another Day Full Of Dread," a song about human ugliness, Oldham interpolates "The Children's Marching Song (Nick Nack Paddy Whack)." It's a self-proclaimed "silly song" that includes this brutal verse: “So I become more lively/ To bury all of the ugly/ Whole persons sometimes/ Must them bodies buried." Much of the songwriting on this album takes from what the listener might already be familiar with and warps it, turns it absurd. It is Oldham's way of spiriting you into his world.

"There’s a lot of songs in here about dressing up as a colleague of time in order to equal or own her. It's obsessive. Songs are inherently about wrastling a few minutes away from objectively larger forces and claiming them as ours," Oldham writes of "Nomadic Revelry (All Around)." This is my favorite annotation in Oldham's book because it is so self-conscious. There are many artists who will say that they make things because they "have to" or because the work just "pours out" of them. For some, there is a mystical quality involved in the creative process, one that is indescribable and close to godly. I believe that, but I can appreciate Oldham's exploration a bit more: Songwriting as an obsessive and borderline selfish way of taking up space, of building something lasting to undermine the indifferent passage of time.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]