Many people only know the Roots as Jimmy Fallon’s band on The Tonight Show. While that should be a criminal offense, it exemplifies how underrated and underappreciated the Roots’ legacy in hip-hop (and all of music) is. There are no prodigious sales numbers to boast. There is no pile of Grammys. Yet solely from an undeniable catalogue of politically minded, incredibly forward-thinking music, they have a largely unrecognized influence on what is far too flippantly referred to now as "the culture." They established themselves by boldly innovating within the tenets of hip-hop, unafraid of being considered weird, militant, or square, and they’ve maintained a stronghold in the game through seemingly endless reinvention and evolution. The "Legendary Roots Crew" name may have begun as a self-bestowed moniker over 25 years ago, but it certainly rings true to this day -- whether you primarily see them now as having a well-earned, cushy gig or as Jimmy Fallon's sidekicks. Neither the Roots’ musical legacy nor their current late-night employment would be possible without the release of Things Fall Apart 20 years ago tomorrow.

Things Fall Apart is named after Chinua Achebe's seminal 1958 novel. By invoking Achebe's book, the Roots foreground their commentary on the state of hip-hop and their own position within it. The fictional work recounts the European invasion in Southeastern Nigeria through the lens of Okonkwo, a strapping warrior, wrestler, and clan leader who seemingly has it all. He has three wives, 10 children, wealth, clout, admiration, and a seat on the council of chiefs. But in the face of imperialism, it is not enough. Toward the end of the book, Okonkwo tries to start a war with his villagers' colonizers, but his fellow warriors don't support him, ultimately cowering into submission.

By 1999, it felt like rap had fully given in to commercial success over its conscious roots as it entered the "bling era." Juvenile had claimed "the '99 and the 2000" for Cash Money, and similar artists and cliques were ruling the charts and airwaves with braggadocios and consumerist raps after labels (largely run by white folks) finally decided to actually begin to invest resources into developing rap acts. The Roots, Common, Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and Nas -- among others -- held the frontline against mainstream rap, but it was ultimately a losing battle as Cash Money, Bad Boy, Aftermath, and No Limit moved millions of units and became the public face of the genre.

The Roots were not quite the wealthy, powerful Okonkwo, but they had faced their own form of exile. The group released their 1993 collection Organix independently while living in London, where they tried building a fanbase after not quite catching on locally in their hometown of Philadelphia. The following year, they toured Europe on the heels of Organix, which would earn them a record deal with DGC/Geffen. Their resulting label debut and sophomore effort, 1995’s Do You Want More?!!!??!, helped define their "organic hip-hop jazz" sound, as Black Thought would call it on the opener "Intro/There’s Something Goin’ On."

But things were still lacking in measurable terms of success. Do You Want More?!!!??! failed to break the top 100 on the Billboard 200 chart, and none of its singles charted or received much radio play outside of Philadelphia. Then the album's 1996 successor Illadelph Halflife showed immense promise and exposed some of the Roots' stewing potential. It peaked at #21 on the Top 200 and included the group's first charting single, "What They Do." This is thanks in part to the fact that the album included features and production credits from Q-Tip, Common, Raphael Saddiq, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and a budding J Dilla.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The critical acclaim for Illadelph Halflife was the perfect setup forThings Fall Apart. On Things Fall Apart, the Roots brought their experimentation to a commercialized rap scene, not unlike Okonkwo's return to his unrecognizable village. However, for all their talent and righteous intent, the Roots were still a band that didn’t quite have an identity. The Philly crew knew not to do "What They Do" and had positioned themselves as the opposition to more mainstream rap acts, but they hadn’t quite been able to sell their aesthetic to the extent that their likeminded peers could. The Fugees had their Caribbean leanings, OutKast were the eccentric Southern lyricists, and A Tribe Called Quest had their Afrocentric, diasporic steez. The Roots hadn't found their "thing" yet. But they would define themselves rather quickly on Things Fall Apart, and it was a marvel to watch them take shape.

The lineup of Questlove, Black Thought, MC Malik B, keyboardist Kamal Gray, turntablist Scratch, bassist Leonard Hubbard, and beatboxer Rahzel was a full-fledged band with a following -- and plenty of anticipation coming into their fourth album. Listening to Things Fall Apart was like accompanying them on their journey of self-discovery, one that would become their best-selling album to date. Things Fall Apart is the first Roots LP to go gold, and the only Roots album to go platinum, albeit 14 years after its release. "You Got Me," Things Fall Apart’s lead single, would win the Grammy for Best Rap Performance By A Duo Or Group. The album itself was nominated for Best Rap Album but lost to Eminem’s The Slim Shady LP. Yet more important than any commercial or critical success was the fact that Things Fall Apart made the Roots an institution.

Questlove had always been the guiding ear of the group, but glimpses of the conductor, curator, and tastemaker we know today were first made very apparent on Things Fall Apart. His individual growth behind the scenes would help solidify the Roots’ sonically daring reputation. Things Fall Apart was the first of the heralded Soulquarian projects that helped the Neo Soul wave flourish at the turn of the millennium. Though he is careful not to take too much credit in his book Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According To Questlove, Quest was the major orchestrator of both the Roots and the Soulquarian collective.

His experience working on D’Angelo’s Voodoo and Common’s Like Water For Chocolate -- both of which came out the following year, in 2000 -- overlapped with the recording of Things Fall Apart, and enabled him to bring them in on the Roots' own music. His finely tuned ear helped organize a who’s who of contributors on the album in general, including D’Angelo, Erykah Badu, Mos Def, Common, Jill Scott, Eve, Beanie Sigel, and Scott Storch, among others. Each of their individual sensibilities were utilized in a way that enhanced the Roots’ already layered sound, without muffling their unique talents.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

D’Angelo’s soulful keys soften many tracks and lend them more of an R&B feel, while still keeping the sound rooted in hip-hop so Black Thought can bob and weave through his verses. Erykah Badu’s hook on "You Got Me" alternates between textured and super smooth, a much needed reprieve from Black Thought and Eve’s rugged deliveries in hard Philly accents. Mos Def and Black Thought trading off on "Double Trouble" could sustain an entire album that would rival hip-hop’s best lyrical duos, but the playful xylophone-driven beat offsets the denseness of their lyricism while paying homage to Afrika Bambaataa and Wild Style legends Double Trouble. J Dilla's syncopated swing can easily dominate a track (as we would see on 2006's Donuts), but on "Dynamite!" it's the perfect bed for Black Thought and Elo's dexterous exchanges. Perhaps the most telling of the Neo Soul sound to come was the aptly named "The Next Movement" which deftly melds together vocals from R&B duo Jazzyfatnastees, scratches from DJ Jazzy Jeff, live instrumentation from Roots members, and interpolations of James Brown’s "Funky Drummer" and Bobby Brown’s "Like Bobby."

Rap always had a heavy reliance on sampling since its younger days. In 1999, the Roots were manipulating samples while incorporating live instrumentation with leanings from other genres and ultimately packaging the hodgepodge of sounds as hip-hop. Lines can not only be drawn to the rest of the Soulquarian projects, but all the way to contemporary albums that synthesize a heavy dose of another genre with rap, like Chance's gospel-doused Coloring Book, Noname's neo soul-leaning Room 25, and Kendrick Lamar's jazz-tinged To Pimp A Butterfly. When TPAB debuted, one of the album's main producers, Terrace Martin, cited the Roots as a source of inspiration, giving him the confidence to know that "any genre can be folded into rap."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Lyrically, Black Thought established himself as your favorite MC’s favorite MC on Things Fall Apart as well, long before he had a scroll from Jimmy Fallon for recognition (as if he needed one), cosigns from Harvard, articles in the New Yorker, or the title of the unofficial most underrated rapper of all time.

Thought is the backbone of the band -- the ever-steady lyrical virtuoso who is often the binder of the group's experimentation and eclecticism. Here, he's often rhyming about how other rappers are going commercial, echoing the opening dialogue of Denzel Washington’s Bleek Gilliam and Wesley Snipes’ Shadow Henderson from Mo’ Better Blues, featured on Things Fall Apart's intro. Gilliam and Henderson were debating what made artists popular in the jazz age. Henderson said, "The people don’t come because you grandiose motherfuckers don’t play shit that they like." Thought and the Roots know that they are the "real" alternative to what’s ruling the radio, but the pocket that Thought sits in lyrically marries the unconventional combination of R&B-infused sonics with aggressive cadences listeners were more accustomed to at the time. Thought is the bridge between the old and new Roots, old and new soul, and old and new rap -- all with a unique style and lyricism matched by very few.

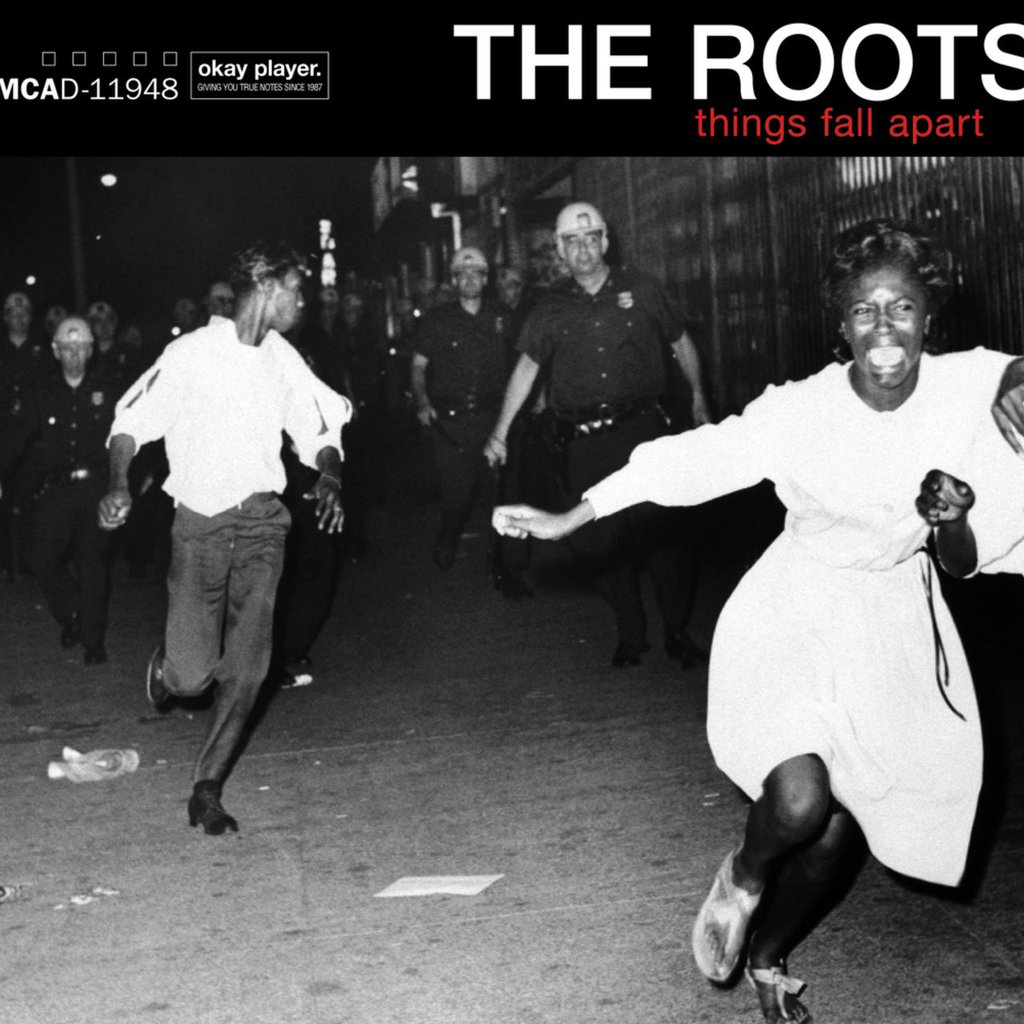

As his name suggests, Black Thought is also the political barometer of the group, and the Roots wouldn't be the Roots without darker political leanings. They had already framed Things Fall Apart politically through Achebe's novel and the harrowing 1960s cover photo of a black man and woman running from riot police in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. But Black Thought embodied the "unflinching and aggressive commentary on society" that art director Kenny Gravillis thought the photo evoked the most out of five potential covers.

Thought has always carried the lyrical load for the crew willingly and skillfully. Even if Malik B held his own here, Things Fall Apart is particularly dependent on Thought's breadth and depth of knowledge as an MC. Especially on the stretch in the first half of the album from "The Next Movement" to "Without a Doubt," Thought deploys provocative imagery. "Black rain fallin' from the sky look strange/ The ghetto is red hot, we steppin' on flames/ Yo, it's inflation on the price for fame/ And it was all the same, but then the antidote came," he raps on "The Next Movement." He rhymes about anything from US foreign relations to water crises, from the ills of capitalism to racism, and ties them all together with style and flare that runneth over.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Things Fall Apart is also the first instance we get of the Roots’ albums as launching pads for other artists. Both Eve and Beanie Sigel make their recording debuts on the album. Jill Scott, who was replaced by Erykah Badu on the final version of "You Got Me," toured to perform the hook on the song in live performances. Scott Storch would take lessons learned during his time with the Roots to produce many hits of his own. In the same way, Wale would sign a major label deal after his feature on "Rising Up" from 2008’s Rising Down. LA underground fixture Blu would raise his profile and ink a short-lived deal with a major as well after two features on 2010’s How I Got Over.

Things Fall Apart is much more than the effort that established the Roots. It’s a blueprint for reinvention, genre-blending, sonic risk-taking, raw lyricism, and unflinching politics all in one. Conscious-leaning giants J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar would not have been able to grow so tall without the Roots anchoring them, and this album's legacy will inspire many more to come. In a country and world where leaders are seemingly hell-bent on perpetuating divisive attitudes, policies, and systems, amplifying the voices of the underrepresented and disenfranchised becomes that much more imperative. The Roots have lifted those voices beautifully for over 25 years now, and continue to do so as the sole predominantly black band that appears on television regularly at the moment. Sure, they don't have a voice or presence on TV more fitting for their legacy, but by taking up that space they're making room for the next band to have that voice and presence. So you can see this band as sidekicks now, if you'd like, but you have to keep your ear to the ground to truly hear the Roots.