Sometimes, the forces of history converge, and people rise out of nothing to become conquerors. Consider, if you will, Beyoncé Knowles, now appearing on half the movie screens in the United States in talking-lion form even though she really can't act.

Beyoncé was bred to be a star. She'd been performing since she was eight years old. That's when she met future Destiny's Child bandmates Kelly Rowland and LaTavia Roberson, all of whom were auditioning to join the Houston girl group that would become Girl's Tyme. Girl's Tyme made it as far as the TV competition Star Search, but they didn't win it, and Beyoncé's father Mathew Knowles quit his job as a medical-supplies salesman to better manage his daughter's hopes and dreams. Mathew put Beyoncé at the front of the new girl group he'd assembled, the one that would eventually be known as Destiny's Child. He pushed them relentlessly, making them practice and exercise and take dance and voice lessons. They'd all sing together in Beyoncé's mother's hair salon.

Eventually, all this paid off. In 1997, when Beyoncé was 16, Destiny's Child made it up to #3 with the sly, flirty "No, No, No." But it was the remix of the song, with the hard-sliding bassline and the Wyclef Jean guest verse, that got the radio play. The original "No, No, No," like the rest of Destiny's Child's self-titled 1997 debut album, was a stiff and sleepy take on lush '70s soul. Beyoncé could clearly sing, but she was being forced to sound older than her years, and the album was boring. Beyoncé would not become a star singing music like that. Instead, she had to wait until R&B got weird.

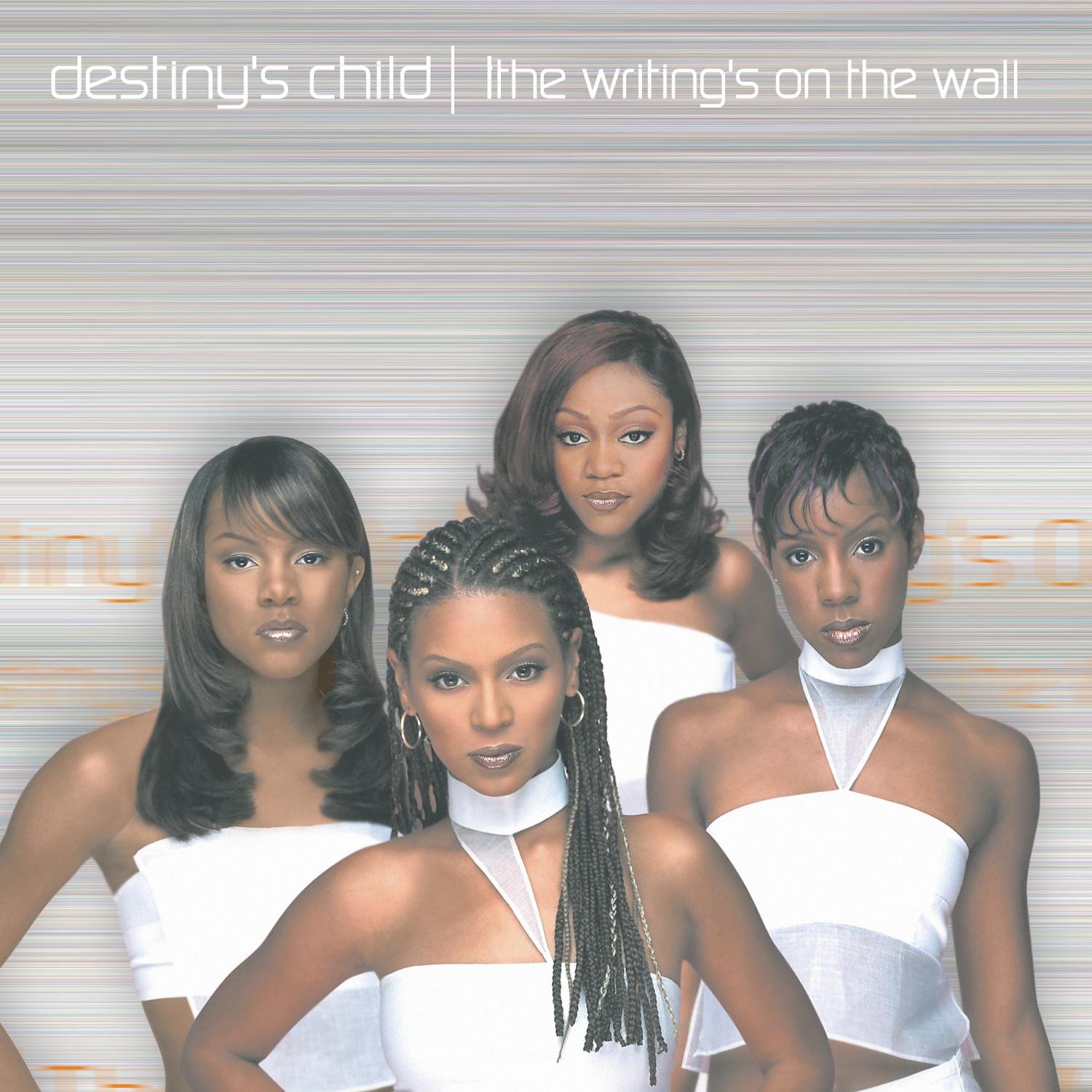

Around the same time Destiny's Child were making that first album, Timbaland and Missy Elliott were reshaping the way rap and R&B would sound. Timbaland's production -- globular bass, tricky counter-melodies, sci-fi beep-whirrs, weird rhythmic hiccups, vast expanses of negative space -- was a radical departure from the relatively straightforward swingbeat of its era. It took rap music months to absorb those new ideas, and it took R&B years. But by the time Destiny's Child made their mind-bogglingly successful sophomore album, it had happened. Three months before The Writing's On The Wall hit stores, TLC's sublime "No Scrubs" made it to #1. On that song, producer Kevin "She'kspere" Briggs took a glimmering and processed acoustic-guitar figure and ran it through a post-Timbaland prism, supercharging it with clicks and blips and stutters. That style became the template for Destiny's Child, who did great things with it and who got huge in the process.

She'kspere produced five songs on The Writing's On The Wall, including two of the four singles. He co-wrote all five of them with his then-girlfriend Kandi Burruss, the former Xscape member and current Real Housewife. When Destiny's Child brought She'skpere and Burruss to Houston, the duo were told that there was only space for one more song on the record. But the duo gave them "Bug A Boo," and the group ended up building the entire album around that sound. Beyoncé, in particular, had a flair for it. Thanks in part to her father's boot camps, she was able to sing intricate and sophisticated melodic lines over these intricate and sophisticated tracks. She was also able to personalize the songs. All four members of Destiny's Child got co-writing credits on the album's songs because they would rewrite the lyrics, twisting them into the right shapes. But Beyoncé in particular could sing this stuff like she meant it.

That post-Timbaland sound is all over The Writing's On The Wall. Superstar producer Rodney Jerkins brought it to the eventual #1 hit "Say My Name," refracting and atomizing a traditional R&B ballad into a skittering, panting masterpiece. Beyoncé co-produced "Jumpin', Jumpin'," another future hit, building a club jam out of oscillating synth-lasers. Missy Elliott herself produced and rapped on "Confessions," adding a computerized alien moan. There are more conventionally mid-'90s R&B moments all over The Writing's On The Wall, like "Sweet Sixteen" or "If You Leave," the duet with the R&B boy band Next. There's even a lovely album-closing rendition of "Amazing Grace" that's clearly there to show the group's pure vocal bona fides. But this is an album with its heart in the future.

It's also an album with a cynical, jaded, sometimes-transactional view of love. All through the album, men are letting down the members of Destiny's Child. On "Bills, Bills, Bills," they're mad at no-account men sponging off of them. On "Bug A Boo" and "Say My Name," they're suspicious, sure their men are creeping. On "Jumpin', Jumpin'," they're ready to cheat themselves. After all, who needs a healthy relationship when the club is full of ballers with their pockets full grown? When a full-grown Beyoncé went back into accusatory mode years later on Lemonade, she had the weight of cultural memory working for her. We'd already known since she was a kid that she wasn't taking any bullshit.

But Destiny's Child itself became a cynical, jaded, transactional entity soon afterward. Original members LaTavia Roberson and LeToya Luckett tried to separate themselves from Mathew Knowles, convinced that Beyoncé and Kelly Rowland were getting more money and attention. They found out that they were out of the group when they saw other girls lip-syncing their parts in the "Say My Name" video. They sued. Thanks to the resulting public-relations shitstorm, Beyoncé spent the next year or so in damage-control mode. But there was no lasting damage. In the end, Destiny's Child got even bigger, and The Writing's On The Wall kept selling.

It sold, and it sold. The Writing's On The Wall debuted at #5, and it never climbed any higher. But as all four singles rolled out, the album kept moving units. Its biggest sales week came after it had been out for a year. In the end, it moved more than eight million copies. And it turned Beyoncé into a star. Beyoncé, who dominated every track on The Writing's On The Wall, was young enough to take immediately to the new sounds that were suddenly reshaping R&B aesthetics. And she'd practiced hard enough that she had the technical skills to handle tracks like that while still broadcasting personality all over them. She was made for her times. She became a conqueror.