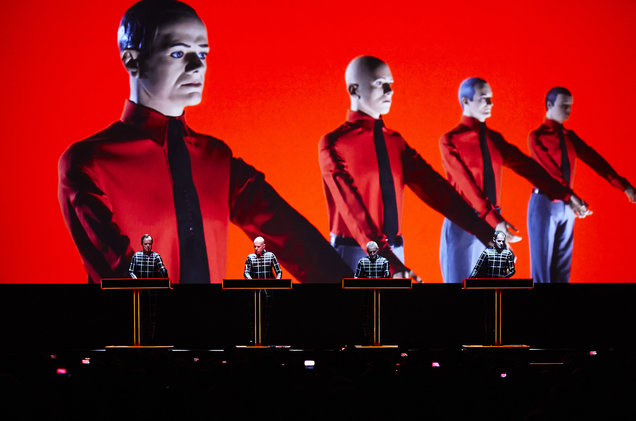

A nearly 20-year legal battle over the unauthorized sampling of a Kraftwerk song appears to finally be near an end after the European Court of Justice ruled in favor of the pioneering German group.

The long-running case -- which carries potentially large ramifications around the use and licensing of samples in the wider music industry -- revolves around a two-second drum sequence from Kraftwerk's 1977 song "Metall auf Metall" (Metal On Metal), which producers Moses Pelham and Martin Haas sampled and looped in Sabrina Setlur's 1997 song "Nur Mir."

Kraftwerk founding members Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider-Esleben have always argued that the producers did not have permission to use the sample and launched legal proceedings in the late 1990s, seeking damages and an injunction of the song.

Since then, the case has slowly wound its way back and forth through the German courts (including twice before the Federal Supreme court) before being referred to the European Court of Justice following an appeal from "Nur Mir"s producers.

On Monday, July 29, the European Court of Justice returned its verdict, ruling that the sampling of a sound recording, even a very short sequence, must be regarded as a reproduction of the original work and therefore require clearance from the rights holders.

There are some important and, on the surface, seemingly contradictory exceptions to that ruling though, which could impact on future copyright infringement and sampling cases in Europe.

Significantly, the court states that in instances where a producer or artist samples a musical recording "in a modified form unrecognizable to the ear" it does not amount to a reproduction of the original work.

What that means in the case of Pelham and Haas versus Hütter and Schneider-Esleben is still to be determined, as that dispute now goes back to the German Federal Court of Justice to decide (in accordance with the European court's verdict), most likely after summer recess.

However, given that the two-second sample of "Metall auf Metall" is very clearly recognizable in "Nur Mir" and plays a key part in its clanging percussion track, it would be a major surprise if the German court did not rule in Kraftwerk's favor.

The European Court of Justice also found that the 'free use' exception part of German copyright law relied upon by Pelham in his defense is out of step with broader European laws.

Representatives of Kraftwerk or Moses Pelham and Martin Haas are yet to comment.

Welcoming the court's verdict, Dr. Florian Drücke, CEO of the BVMI trade group that represents the German recording business, said in a statement that the ruling creates "a clear framework… as to when sampling falls under artistic freedom and thus can outweigh property rights, and when it does not."

"This is a great result for artists who create original content, creative artists, and labels," Gregor Pryor, co-chair of the global Entertainment and Media Group at Reed Smith, tells Billboard. "It gives anybody who is complaining about unauthorized sampling a stronger platform from which to fight."

It does, however, raise a new set of issues around the specific use of samples, he says. "What this judgement may do is lead to a school of thought among artists that they can get away with sampling if they adapt or change the sound recording from how it originally sounded. The test set out by the European court is that for a sample use to be legitimate, the recording must be modified so that it is 'unrecognizable to the ear.' There will likely be questions in future about such transformative use and the extent to which an artist has to modify a sample to enable the legitimate use of it."

Raffaella De Santis, senior Associate at London-based law firm Harbottle & Lewis calls the European Court ruling "a final victory for Kraftwerk" that carries important repercussions for rights owners of sound recordings in Europe.

"There is no European-wide definition of what a 'sample' is, nor, until this case, were there clear guiding principles about what extent and nature of use of a copyrighted work could be said to be infringing," she tells Billboard. "We now have guidance that sampling even a very short sequence from a sound recording may in principle be infringing, unless it is modified in a way which makes it unidentifiable."

That news will be welcome clarification for rights owners, says De Santis, but she notes "it could have a chilling effect on artistic expression in an increasingly remix culture."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

This article was originally published at Billboard.