There is no statistical database that will inform me how many albums have begun with a pick slide, but I have an ironclad certainty that the Get Up Kids' Something To Write Home About is the only one introduced by a double pick slide. Bands almost always use pick slides as a celebration of what’s to come, replicating the steel-on-steel effect of a roller coaster on the upswing, anticipating a righteous guitar solo or a massive group chorus, something so badass it can’t really be set to words. I wouldn't put such a metal maneuver past the Get Up Kids -- witness their cover of Motley Crue's "On With The Show" from their B-sides collection Eudora. On more rare occasions, it's an act of violence or an expression of unspeakable rage. That's what I hear when "Holiday" kicks off Something To Write Home About: just how pissed the Get Up Kids had to be when that record dropped 20 years ago this week.

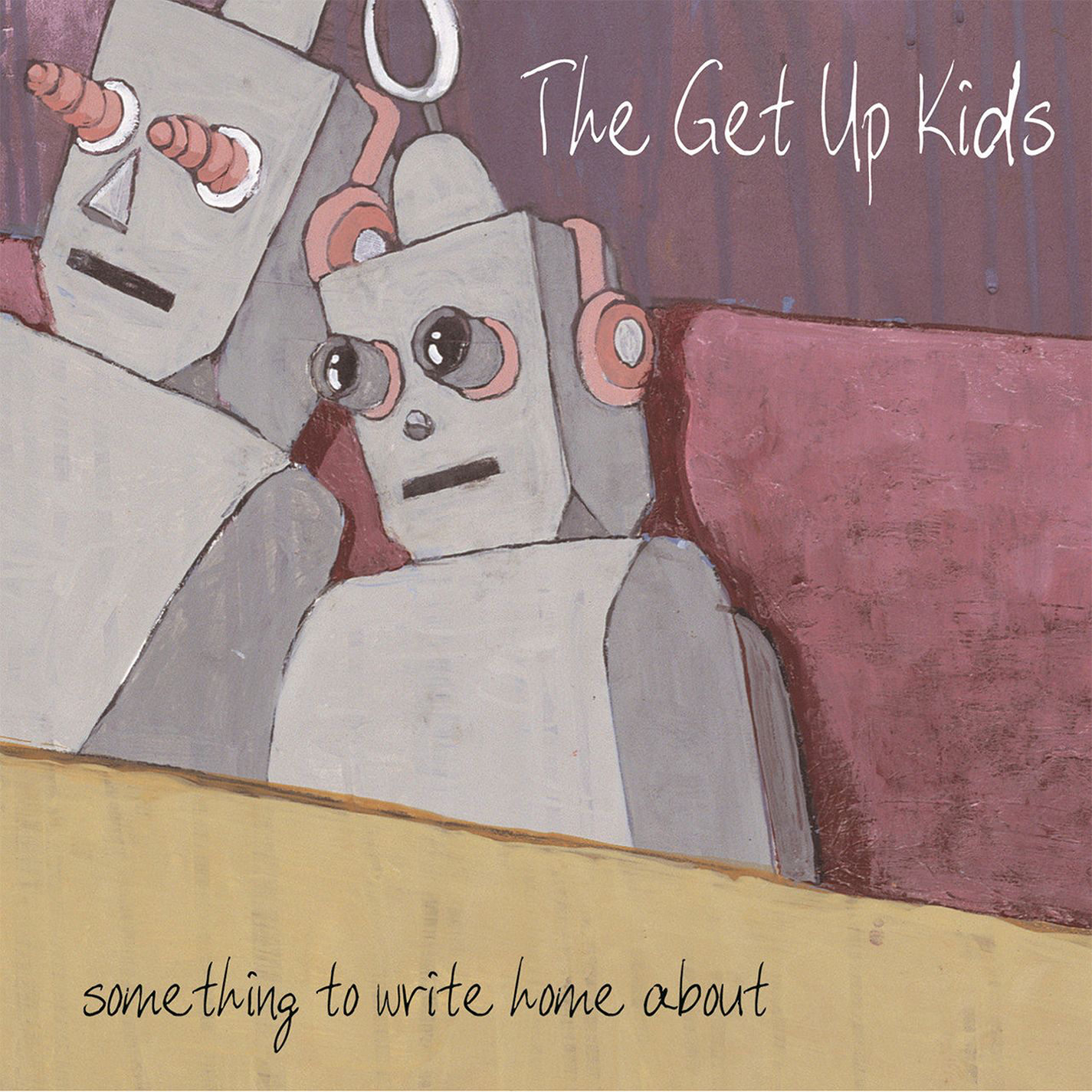

To reiterate, yes, I am referring to the Get Up Kids' Midwestern emo-pop classic Something To Write Home About. The one with cover art depicting, as Pitchfork wrote in one of its many era-defining pans at the genre's expense, "slumberous robots snuggling on a sofa, presumably watching banal television." The one with "10 Minutes," one of the few late-'90s tracks that still pops off at Emo Nights that don’t really play emo. The one with a song called "Valentine" where the chorus is actually, "Won't you be my valentine." The one with freshman dorm acoustic staple "Out Of Reach" and soft-serve closer "I'll Catch You," a song Matt Pryor wrote about his future wife. Songs like those explain why Universal was trying to pry the Get Up Kids from the surprisingly strong clutches of Doghouse Records, but the bulk of Something To Write Home About is explicitly about feeling like the collateral damage in a major-label bidding war.

"Who'd have thought we’d represent, when I can't take a compliment," Pryor wonders during "Action & Action," and listening to 1997's Four Minute Mile, yeah -- who'd have thunk it? There’s a certain type of emo diehard who swears against all evidence of songwriting growth or production values that a band's debut is inherently its best work, because of its "rawness" or some other quality that doesn’t translate so well outside of a VFW basement -- examples include the Promise Ring's 30 Degrees Everywhere, Modern Baseball's Sports, and Title Fight’s Shed. Now, "Don’t Hate Me" is an unimpeachable spite-punk classic, while "Stay Gold, Ponyboy" and "Michelle With One 'L'" influenced emo song titling for decades to come. Otherwise, I don’t mind saying that the songwriting on Four Minute Mile lacks finesse or that it sounds like it was recorded inside an empty keg from a University of Kansas frat party or that Matt Pryor's singing is almost always off-key, because he'll tell you the same thing. But this is why I'm probably better off as a critic than an A&R.

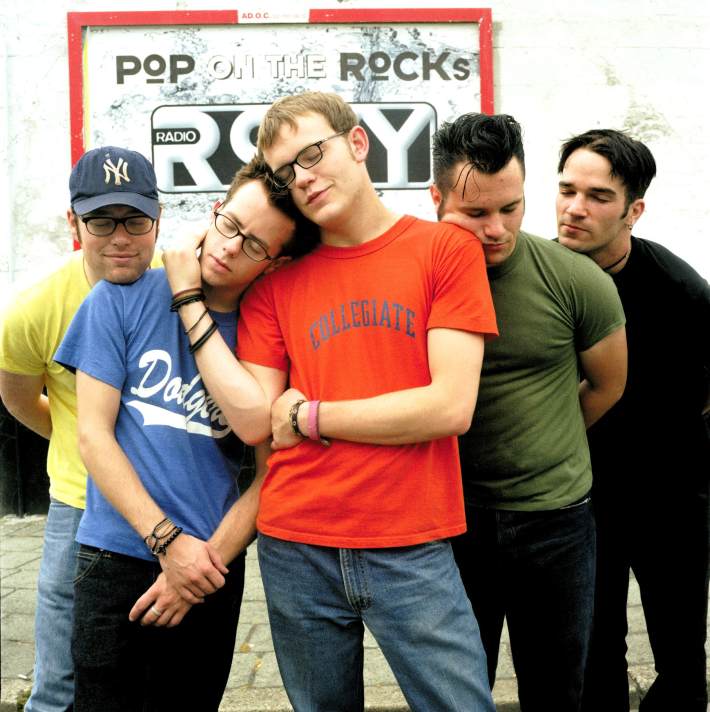

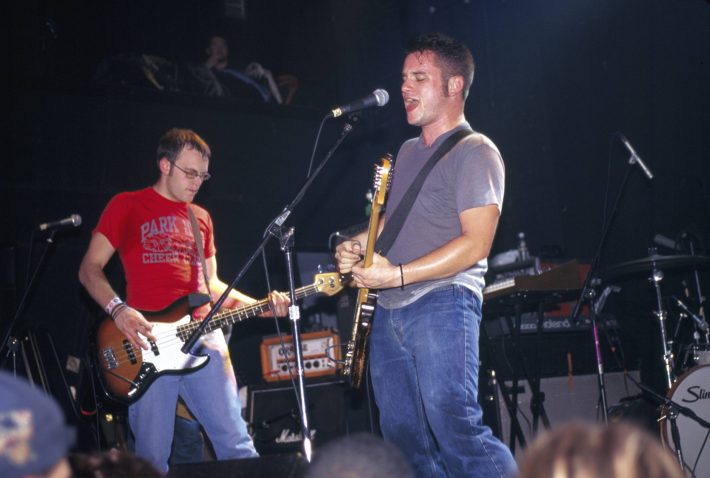

Emo had yet to achieve its commercial breakthrough, but pop-punk had been a reliable seller for most of the decade and Get Up Kids could conceivably be marketed as either. They'd evolved from the remnants of Kingpin, once referred to as "the talk of the Olathe indie scene" in an early band bio. Their early gig itinerary looks supernaturally charmed: Get Up Kids played their first show ever with Boys Life and Karate. In 1997 and 1998 alone, they toured with Promise Ring, Mineral, Jejune, No Knife, and Jimmy Eat World and also played a random show in Wilkes-Barre with Converge. There’s a point in nearly every Get Up Kids interview where you can practically see the wind go out of Pryor as he gets asked about the "e word," and while he’s in a place of acceptance now, he correctly notes that they would’ve been considered indie rock had they not been on Doghouse or hung out with so many hardcore bands.

Among them was Kansas City's Coalesce, which featured James Dewees on drums. During one of their many shows together, Dewees threw his tom on the floor and injured a bystander in the process. The Get Up Kids thought it was awesome and added Dewees to their lineup (and their lease) as a keyboardist once Coalesce went on hiatus. Like Danny DeVito on It's Always Sunny In Philadelphia or Walton Goggins on The Righteous Gemstones, Dewees immediately made a solid project exponentially funnier and worthy of being taken seriously. While his hyperactive stage antics and goofball side project Reggie And The Full Effect rubbed some the wrong way, the rest of the Get Up Kids took his surprisingly impressive piano chops as a challenge -- both Pryor and Jim Suptic wrote melodies strong enough to overpower his yo-yoing synths on "Action & Action" and "10 Minutes" and found a completely unexpected tenderness on ballads like "Company Dime" and "Long Goodnight." The clearest example of their instantaneous chemistry comes on "Mass Pike," a mixtape makeout classic from the preceding Red Letter Day EP; had they included it on Something To Write Home About, they might’ve gotten "Death Cab For Cutie big" before Death Cab themselves did (think of it as their "Photobooth"). That said, there's a moral conundrum in praising Dewees' contribution right now -- a few weeks ago, he was unceremoniously kicked out of the Get Up Kids and I'm inclined to believe this story is not going to end well.

But while the Get Up Kids were clearly ready to level up back in 1998, they spent months negotiating with the Universal subsidiary Mojo Records and "sitting around with our thumbs up our asses," a familiar scenario to emo bands who were both lucky and unlucky enough to get a crack at the major leagues in the late '90s. There was a lot of money going around, and the much bigger bands already making a lot of that money demanded more immediate attention. But while Mineral, Jimmy Eat World, and Jawbreaker were understandably lesser priorities on Interscope, Capitol, and DGC during the alt-rock goldrush, here's a partial list of Get Up Kids' labelmates on Mojo: Cherry Poppin' Daddies, Reel Big Fish, Goldfinger.

The Get Up Kids originally decided on Mojo after dragging their feet with future emo powerhouse Vagrant Records because -- remember, this is 1998 -- it initially felt like a lateral move from Doghouse. Vagrant had put out a couple of albums from Face To Face and the Hippos by that point, lesson being that any punk band with commercial aspirations needed to make nice with ska at the time. The band split the difference, signing with Mojo while keeping a management deal with Vagrant. But after half a year of exhausting negotiations with Mojo, they backed out of the deal and opted for Vagrant after all. "We were already working with them through management," Pryor remembers, "and we said, fine, just give us the money."

Before any of that could happen, they had to find a way out of Doghouse, who, despite their superficially punk rock ethics, wasn’t about to let a cash cow leave the pasture. Get Up Kids fulfilled their contract with the Red Letter Day EP, whose bitter title track is directly aimed at Doghouse’s Dirk Hemsath: "I trusted misleading promises worth repeating/ How could you do this to me?" (Having eventually joined Spoon in 2007, bassist Ryan Pope has been in two bands that wrote vicious songs about their former label bosses.) They also forfeited the future rights to vinyl, which means that Pryor didn't even bother listening to Doghouse’s 2009 reissue of Something To Write Home About.

Get Up Kids' short-lived relationship with Mojo presents one of emo's great "what if?"s - if the deal stuck, would they have peaked as an opening act for Goldfinger? If Vagrant Records hadn’t gotten a boost from Something To Write Home About, would they have the resources to launch Saves The Day, Dashboard Confessional, and Alkaline Trio? Vagrant co-founder Jon Cohen financed recording sessions by borrowing money that his parents obtained by mortgaging their house -- something Pryor wasn’t aware of until only recently. And even now, as Get Up Kids has been surpassed in popularity by seemingly every Vagrant band to follow, Something To Write Home About still sounds like the first emo album worth literally betting the house on.

There were poppy bands in emo, but few that sounded like they could realistically hang with both blink-182 and Foo Fighters on MTV. Jimmy Eat World absolutely could once they hooked up with a label that gave them the time of day and ditched all the drum loops and bells and whistles. But otherwise, Braid and the Promise Ring were too quirky, Saves The Day hadn't quite shed their hardcore origins, and Texas Is The Reason and Mineral were too artsy and esoteric. Something To Write Home About, meanwhile -- I mean, if you're reading this, I imagine you've sung "Action & Action" or "Holiday" in your car and know their pleasures to be self-evident: the sweetness of their melodies slightly masked by the bitterness of the lyrics and the granularity of Pryor's voice, all of it occupying that perfect nexus between punk, emo, indie rock, and pure power-pop. I think of it this way: Something To Write Home About is to Superchunk what Nevermind was to the Pixies, grafting bigger hooks and less obtuse emotions onto a "college rock" template so it speaks to high school, middle school, and beyond. (Sidenote: The Get Up Kids' cover of the Pixies' "Alec Eiffel" is the most concise exploration of the difference between "emo" and "indie rock," i.e. play it faster, with more drum fills, breakdowns, and harmonies).

Consider the three dominant influences Pryor has named for Something To Write Home About: Jimmy Eat World's Clarity, Wilco's Summerteeth, Foo Fighters' The Colour And The Shape, all of which were examples of bands likewise taking bold steps from their humble origins (Weezer had also been in constant rotation since the beginning, but that should go without saying).

If this is new information, it's easy enough to reverse engineer the Get Up Kids’ process in building on Four Minute Mile: bigger, cleaner guitars, gooier emo sentimentality, longer songs, Moog keyboards. While American Football, Look Now Look Again, Clarity, and Through Being Cool were examples of emo being pushed forward in 1999, Something To Write Home About found a new center. Jimmy Eat World, Foo Fighters, and Wilco are staples of any modern band that looks to slightly left-of-the-dial popular rock from the late '90s, when at the time, those three occupied completely different spheres of consciousness. The Get Up Kids have obvious descendants in You Blew It!, Oso Oso, Charly Bliss, and prior openers PUP and the Hotelier, all bands who’ve benefited from softened critical attitudes towards emo. But they were also a sneaky presence even around the time when 2011’s There Are Rules found them at their nadir of public consciousness: If the Bob Weston-produced Four Minute Mile had Something To Write Home About's melodic purity and was recorded by the other guy in Shellac, you get Cloud Nothings. A little less Superchunk and a lot more Replacements and you’ve got Japandroids.

It’s a center that wouldn’t hold for the Get Up Kids. Though this year’s Problems was a solid return to straight-ahead pop-rock, the 20 years between it and Something To Write Home About were pretty grim, as they've been for many of Get Up Kids' peers who’ve kept going but never got big enough to weather some duds like Jimmy Eat World or Death Cab For Cutie. 2002's On A Wire wasn't exactly a career-killer: Get Up Kids still do fairly well to this day and, as with Saves The Day's In Reverie and Promise Ring's Wood/Water, there’s a vocal minority that embraces their foray into floral indie-pop as a misunderstood classic.

Pryor will sometimes say that 2004's Guilt Show is their best record made under the worst circumstances. They were barely talking at that point, and five years after going all in on the Get Up Kids, Vagrant couldn’t be bothered to put any promotional push behind it. They self-released There Are Rules in 2011 and, in our interview this year, Pryor and Suptic told me that even their close friends weren't aware of its existence. In light of the wildly positive reception granted to their peers who came back from long hiatuses, I wonder if Something To Write Home About might be undervalued now: Would that have been the case if Get Up Kids simply broke up after On A Wire?

Then again, just about every positive writing about Something To Write Home About views it from an uncritical standpoint of teenage nostalgia. "Ah, to be an angst-ridden teen," begins a 2011 reappraisal in Consequence Of Sound, which praises Something To Write Home About as "a perfect trip down memory lane" and "a 45 minute loud, fast, and whiny album about lost love." A PopMatters review of the 2009 reissue asserted, "It's well worth basking the nostalgia," while Drowned In Sound's reviewer conceded, "The lenses through which I view the record are admittedly a smidgen rosy-hued." These are people who've heard Something To Write Home About and even loved it without paying attention to the actual lyrics.

Granted, there are very few ways to interpret "Valentine" or "I'll Catch You," but what about lines like these: "You're just a phase I've gotten over anyhow," "I'm not bitter anyway, but I didn't want it to turn out this way," "I'm still waiting for you to get over this," "Everything we’ve found says, 'Make your own destiny.'" They're all taken from songs that are quite clearly inspired by their shitty experiences at all levels of the music industry, and yet they can all easily be interpreted as being about a crush who doesn't like you back. Pryor never really lost that ability to blur the line between adult angst and teenage anxiety. A friend once told me they lost their virginity while On A Wire’s "Overdue" was playing, and to some extent, sure -- it's a pretty acoustic song played by a band generally beloved by people in their teens. It's also almost certainly about an absentee dad.

This speaks to the frequent source of tension between the creators of some of emo's most popular works and the people who listen to them. This is music made by people in their late teens or early 20s, on the cusp of so many forms of self-actualization, questioning their decision to put their lives on the line as career musicians rather than a band playing in basements. Yet it usually finds an audience of people several years younger. As a result, the ongoing joke at lyrics depositories ranging from Genius and songmeanings.net is that everything is probably about a girl. And that goes a long way towards explaining why Something To Write Home About continues to resonate even at an age where new relationships don't come close to having the same stratospheric stakes they did when you were 19: It's easier to focus on "Company Dime" and "Red Letter Day" and all the songs that speak to the challenges of adapting to the permanence of change in careers, friendships, and philosophies. "What became of everyone I used to know?" Pryor yells on the album's first line, having watched the convictions and relationships upon which Get Up Kids based their lives crumble underneath them. And so they need both of those pick slides to tell the two sides of the story -- damn right they’re pissed off, but they've made a fucking kickass rock record as revenge.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]