When Mos Def's debut album Black On Both Sides arrived -- 20 years ago, tomorrow -- it was a refreshing breath of nasty New York City air of the Brooklyn variety. If you’ve ever lived in or even just visited NYC, then you know sometimes it has the most stale, putrid, muggy air that will ever fill your lungs. For an album so staunchly rooted in Brooklyn and hip-hop history, to exude that air and still sound revitalizing was quite the feat.

On paper it didn't seem like Mos Def, born Dante Smith, had the résumé to qualify him for a push to rap's upper echelons as the millennium changed over. He executed the rap superstar playbook somewhat backwards. He had the hood bona fides -- hailing from the Brooklyn neighborhood Bedford-Stuyvesant when it was arguably at its worst -- but in a time when rappers weren't shit if they hadn't diversified with a clothing line and acting roles, he was an actor first. He made his professional acting debut in an ABC TV movie in 1988 at age 14 and went on to land a role as the oldest child on the sitcom You Take The Kids. He was also Bill Cosby's sidekick on the short-lived show The Cosby Mysteries, and appeared in several commercials including a Visa check card ad where he pretended to geek out upon meeting Deion Sanders.

[videoembed][/videoembed]

Mos clearly wasn't about gangster shit, bling, or any of the other tropes that were soon to take over in the decade leading up to his full-on leap into rap. That made him an interesting dark horse to ride in the opposite direction of where popular rap was headed, and it seemed no one knew he would put conscious rap on his back at a time when it desperately needed to be carried into the new millennium.

Rap was at a critical juncture. The culture of hip-hop and the medium of rap were becoming more defined as separate entities while still occupying the same space as the century rapidly came to a close. At the 1999 Grammys, Lauryn Hill claimed the first ever Album Of The Year award for a hip-hop and R&B release, with the tour de force that is The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill. But at the same time, Juvenile and Cash Money foreshadowed a commercial rap boom when they declared both 1999 and 2000 were theirs on one of the biggest hits of the year, "Back That Azz Up." Dr. Dre's 2001 would earn a gold certification in its first week en route to a platinum plaque with over 90 seconds of audio from a staged orgy on it.

There is more of a peaceful coexistence of rap on top and hip-hop in the underground now, but 1999 saw a second wave of tension between artists who were considered to be continuing the traditions of hip-hop and those who were perceived to be selling out for money and fame. It had happened once before in the late '80s and early '90s, when rap moved out West and many hip-hop traditionalists on the East Coast thought N.W.A were sensationalizing their lifestyle to pimp it across the country under the guise of "street knowledge." Hence Common’s disappointment with the game in his 1994 track "I Used To Love H.E.R."

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

It seemed the first battle was lost as sales sky-rocketed while any semblance of consciousness in the mainstream was going to die along with Tupac and the Notorious B.I.G. So this second wave of resistance against the commercialization and globalization of hip-hop had much more urgency. It felt like a last stand against what was most likely inevitable.

Rap had already existed and thrived in other regions, but traditionalists, especially those in the five boroughs of NYC, felt it was more derivative each time another region got its hands on it. New York still occupied the majority of the charts with five of the 10 rap albums with the highest first week sales in 1999, but the gap was closing quickly. In addition to other regions gaining ground, albums from politically savvy veterans like Public Enemy or the Sugarhill Gang and newcomers like Nas and the Roots failed to register blips on the popular radar and even fell short critically in some cases. It was becoming dismal for fans and artists of substance alike, and though they knew they were on the losing team in terms of sales and popularity, one MC would give them a last glimmer of hope.

In many ways Mos was perfectly groomed to lead the conscious fight at the turn of the millennium. He watched hip-hop make its way through the NYC boroughs, and saw Biggie Smalls win freestyle battles on Bed-Stuy corners, as he remembered in the documentary Freestyle: The Art Of Rhyme. He saw one of the biggest superstars of rap as a "local cat," and would never forsake his Brooklyn roots no matter how high his star rose. He fully understood the exigence of the moment, fittingly making his recorded debut on De La Soul’s 1996 warning cry Stakes Is High. The Black Dante fits in seamlessly rhyming alongside veterans Posdnuos, Maseo, and Trugoy on "Big Brother Beat," but he invigorates the track with his fresh, signature flow in just eight bars.

That Native Tongues tie would lead to him showing the world much more of what he could do alongside fellow crew member and Brooklynite Talib Kweli on Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star in 1998. From Brooklyn to Africa it was hard to find someone tapped into rap that wouldn’t respond to "One, two, three... " with "Mos Def and Talib Kweli-i-i!" The perfect pairing established both as firmly local, but worldly MCs with head-spinning rhyming abilities. The album only hit #53 at its peak position on the charts, but it was critically beloved and caught the attention of the zeitgeist. Even so: Despite the buzz, there were still doubts about how the mighty Mos would perform commercially and fit into the changing landscape of the mainstream.

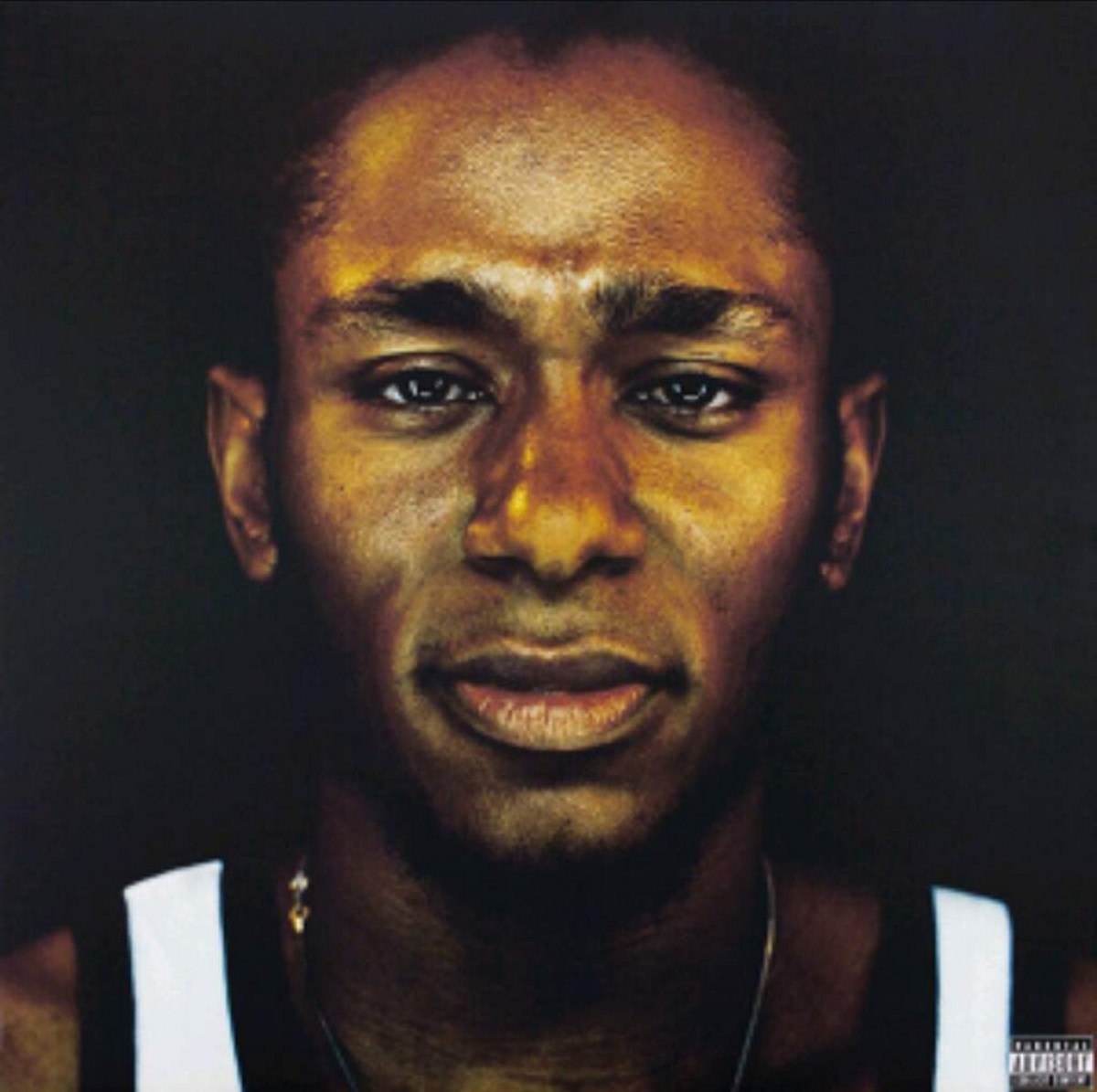

Enter Black On Both Sides -- a marvelous solo debut from Mos Def that would briefly, yet brilliantly, blackhole some of the spotlight from the commercial takeover and give it back to hip-hop’s early tenets, back to New York and cognizance. Four months after its release, the album would hit number one on Billboard's Top Rap Albums Chart and be certified Gold, signifying 500,000 units shipped. Back then, a lot of big rap albums would go Gold or close to it in their first week. Yet the album reaching those heights after moving just 78,000 units in its first week meant people were hooked long after the initial rush of the album’s newness. Ingenuity often takes time to sink in.

It’s not hard to see why the album grew on listeners. Black On Both Sides possesses a wonderful depth and breadth in the midst of a rhyme clinic with a steady current of blackness and Brooklyn as its lifeblood. The man either says, spells, or alludes to Brooklyn over 35 times on the album collectively, and does so 19 times on the track "Brooklyn" alone. The constant shoutouts don’t feel like overkill because he roams so far away home in the number of topics he touches on.

The Mighty Mos addresses the state of hip-hop on the intro "Fear Not Of Man," the importance of community on "Love," lust on "Ms. Fat Booty," the dangers of flexing too hard and living life too fast on "Got" and "Speed Law," the global water crisis on "New World Water," the legacy of black music he is attempting to keep alive on "Rock ‘N’ Roll," escaping poverty on "Climb," black social mobility on "Mr. Nigga," and much more. He does it all with dazzling wordplay, captivating storytelling, sophisticated similes and metaphors, and complex rhyme schemes.

Immediately he lets everyone know he's in tune with what’s happening to the rap game on the intro "Fear Not of Man," and positions himself as someone who should be heard in the matter. Yet it's not some self-aggrandizing spiel. It's simply an answer to a question: "Yo Mos, what's getting ready to happen with hip-hop?" He replies: "Whatever’s happening with us." He goes on to explain that "Me, you, everybody, we are hip-hop" and "Hip-hop is about the people."

Though he offers tidbits about people not being valuable because they "got a whole lot of money" -- setting himself in opposition to the birth of the bling era -- he doesn't come off as preachy or corny. There is a measured nonchalance that lets you know he's spent a lot of time contemplating the fate of the culture he loves, and he's not worried. It's the perfect first offering to set the tone for the album because he comes off as knowledgeable, but he isn't "trying to kick knowledge," as Nas would say. That is a delicate balance to strike and Mos does it well, making what follows on the 17-track behemoth easy to digest and accept.

The intro frames the subsequent "Hip Hop" perfectly. It's understood why Mos has to keep the OG Spoonie Gee alive with the opening line "One for the treble, two for the time." Lines like "The industry just a better built cell block" still have plenty of bite, but they don’t come off as condescending. The sharp barbs feel more like a man who cares deeply for his people, his culture, and his music than some prophet sent to deliver the rap game from evil and temptation. The transition into the wonderful storytelling on "Love" further establishes his conviction and what he's fighting for. His depiction of the love and warmth he felt despite a poor upbringing in the Roosevelt housing projects leads listeners to realize there is so much lost when a rapper's downtrodden community is exploited for the sake of image and profit.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Mos continues with the engaging storytelling on "Ms. Fat Booty," subverting the rise of the "video hoe" moment where women were basically only cast as eye candy ornaments. His story of how Sharice opened his nose up is masterful; it's a testament to Mos' skill that he was able to work an Idaho Potato into a rhyme and not come across irredeemably cheesy. Perhaps the best part of this song is that you can picture all of this going down in a Brooklyn club and continuing in the neighborhood, like a Spike Lee screenplay. Up to the halfway point of the album, it's fair to say he hasn’t even left Brooklyn yet, but it's already captivating.

When he does exit the borough, things get even more interesting. Dude comes with some smooth singing chops on "UMI Says," and that change in form signifies a relocation from the local to the global geographically, but also a shift from a specific blackness in Brooklyn to blackness internationally and historically. This is the first sense we get of Mos Def the traveler, theologian, and philosopher. The stretch from "UMI Says" to "Climb" and from "Mr. Nigga" to "May-December" showcase how far Mos could wander despite being firmly rooted in Brooklyn. From the Arabic words -- Umi (mother), Abi (father), Jiddo (grandfather) -- on "UMI Says" to the nations without clean drinking water that come to mind on "New World Water" to the thorough statistical analysis of inequity that is "Mathematics," Mos goes places where probably 95% of rappers don’t have the knowledge or skill to follow.

What partly ties everything he expands on together is the steady current of blackness underneath. "Rock 'N' Roll" in particular highlights a black legacy in rock music that you still can't find in history textbooks to this day, featuring everyone from Chuck Berry to Bad Brains. Lines like "Fools done upset the Old Man River/ Made him carry slave ships and fed him dead niggas" on "New World Water" reminds you that his skin color informs his perspective first and foremost. "Mr. Nigga" reminds you that other people’s perspectives are informed first and foremost by his skin color as well, no matter where he gets to in life. "Habitat" shows you that there are Brooklyns all over the country, and all over the world with resonant lines like "Son I been plenty places in my life and time/ And regardless where home is, son home is mine."

Another aspect that keeps Black On Both Sides cohesive is its production. Though this album isn’t quite Questlove and company locked in a studio together being geniuses, it is one of the more loosely affiliated Soulquarian projects. The sonics are not as groundbreaking and quintessential as they are on D'Angelo's Voodoo or Erykah Badu's Mama's Gun, but they're smart and sophisticated in matching Mos' every move. (Mos was also heavily involved on the production side of the album, as he tends to be.)

On "Got," Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest and production crew the Ummah (with J Dilla and Q-Tip) keep things just engaging and varied enough to not be boring and let Mos' lyrics shine. We of course can't forget the legendary DJ Premier lending some classic New York boom bap and triumphant horns on "Mathematics." A young 88-Keys also contributes some subtle brilliance on the keyboards on "Love," "Speed Law," and "May-December." No sound ever detracts from Mos' voice; they only serve to uplift and keep things moving.

More important than the relationship between Mos’ vocals and the sounds surrounding them, the production subtly enhances the motif of blackness. Peep this list of samples and tell me it’s not one of the most melanated things you've ever heard: "Fear Not For Man" by Fela Kuti (on "Fear Not Of Man"), "One Step" by Aretha Franklin (on "Ms. Fat Booty"), "Anyone Who Had A Heart" by Dionne Warwick (on "Know That"), "A Legend In His Own Mind" by Gil-Scott Heron (on "Mr. Nigga"), "We Live In Brooklyn" by Roy Ayers (on none other than "Brooklyn"), Angela Davis' interview with Art Seigner (on "Mathematics"), James Brown’s classic "Funky Drummer" break (also on "Mathematics"), and "On And On" by Erykah Badu (again on "Mathematics").

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Though he strays far from Brooklyn in the breadth of topics he addresses, the borough's steady presence is the first sign of how the album is aging. Mos Def refers to Brooklyn as Bucktown, and the album feels like a time capsule for a Brooklyn that no longer exists. The "luxury tenements" that Mos Def foreshadowed on "Hip Hop" indeed "choke the skyline" as deep as Bushwick and Flatbush. The areas he names where people get "got" have been gentrified.

No longer is the intersection of Broadway and Myrtle "black as midnight" as he describes it on "Mathematics." Silly awning ordinances make businesses that have been thriving for decades look like they'll be shut down soon. Murals depicting a white woman adorned in chains with pendants tell people to "Protect ya neck." Google swoops in with ads that tell people who have lived in Brooklyn for decades that "You don’t know Bed-Stuy (yet)." Rents sky-rocket and displace multigenerational families, forcing them deeper into Brooklyn until rent in that area becomes unaffordable and they have to move again. The Brooklyn the Black Dante refers to is sadly gone and mostly colonized.

The album has aged beautifully in other ways, though. There are clear sight lines to contemporary, politically conscious albums like J Cole’s KOD. Black On Both Sides is still a blueprint for any conscious album that makes mainstream appeal bend to its sensibilities, such as recent classics like Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp A Butterfly, Solange's A Seat At The Table, and D'Angelo's Black Messiah. It's less than 100,000 copies away from a Platinum certification, and could reach the milestone soon with its 20th anniversary possibly providing a resurgence in sales.

Mos Def has turned into quite the traveler since Black On Both Sides, giving even more credibility to his hints of far-flung wisdom on the album. He had trouble leaving South Africa after spending three years living in Cape Town. He started performing under his Muslim name, Yasiin Bey, and has since dropped four more albums to varying critical receptions. He has contemplated retirement several times, but also promised three more albums during the rollout for his latest offering, Dec 99th with producer Ferrari Sheppard. Though Mos more often than not comes correct on the mic, only 2009's The Ecstatic approaches the end-to-end, how-dare-you-skip-a-track greatness of Black On Both Sides.

Bey's more current ups and downs in his personal life present an opportunity to explore his legacy as an artist, where he fits in the conversation of the great conscious rappers, the significance of Black On Both Sides over time, and the complications of being a cognizant artist at a time when they are endangered in the mainstream -- especially after fighting the good fight for two decades. Any interest in the forthcoming Black Star followup album comes more from the nostalgia and legacy of Black On Both Sides than anything else in Bey's or Kweli’s solo catalogs.

Black On Both Sides can be seen as an extraordinary solo debut, an unlikely commercial success, an influential framework for unapologetically black albums that make noise in the mainstream, the best offering ever from Mos Def, or a loving time capsule for a Brooklyn lost. There is arguably no other hip-hop album released in 1999 with as much dimension and impact. As a Brooklyn resident, I don't hear Mos' voice waft through the air with the frequency and heft of the late Notorious B.I.G.'s, but on the occasions I hear Black On Both Sides, no Google pin drop could ever locate me and the melanin in my skin more accurately.