"One step forward! Five steps back! One cool record in the year of rock-rap!" That was Kathleen Hanna, gritting her teeth hard, on "FYR," a 2001 song from her band Le Tigre. "FYR" is not a triumphant song. It's a song about watching the idea of equality shudder and stall, about watching shit get worse when it's supposed to be getting better. And yet that line is also a god-level flex.

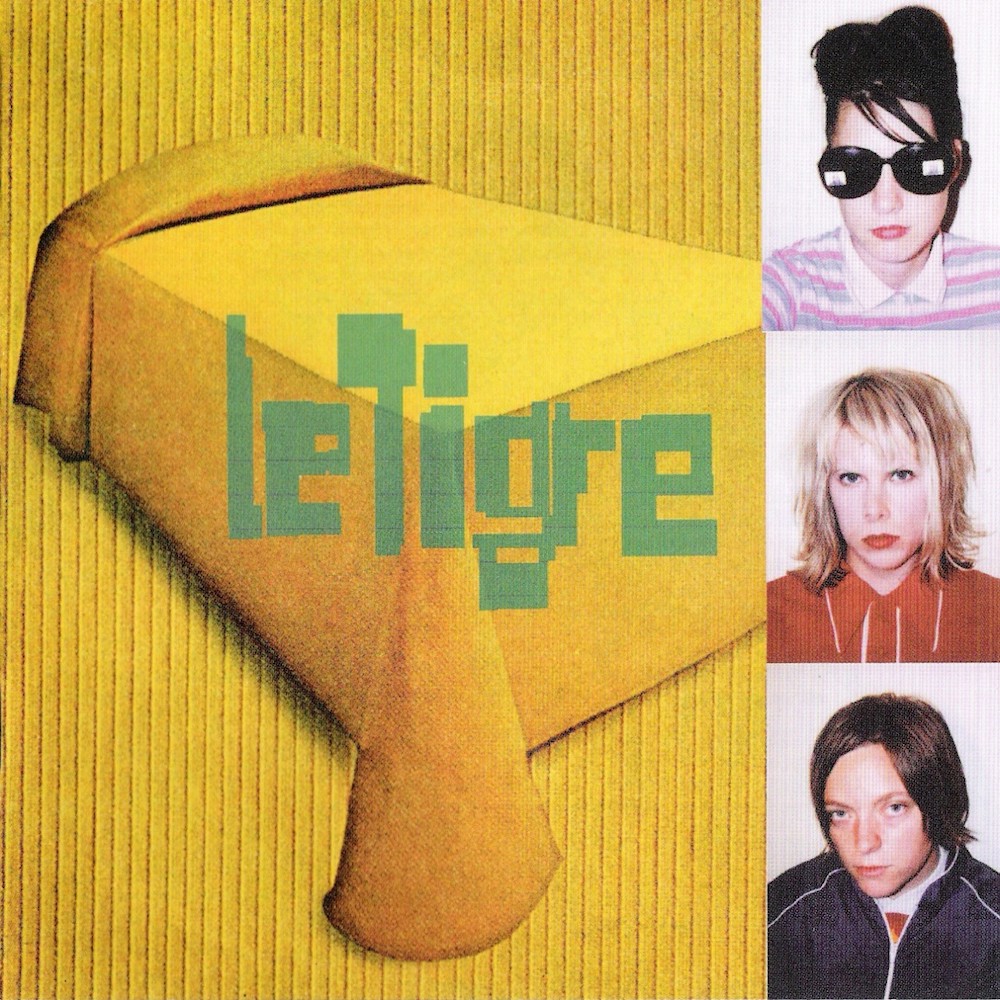

In 1999 -- the year of Limp Bizkit's ascendance, of Woodstock '99, of the dream of the '90s dying in front of everyone's eyes -- Le Tigre came out with Le Tigre. Le Tigre's self-titled debut album wasn't the one cool record of 1999. There were lots of cool records that year. But Le Tigre was a cool fucking record. And even in that moment of early-Bush-era darkness, Hanna still had enough swagger to talk her shit and let everyone know.

Le Tigre's first album, which turns 20 tomorrow, is an example of that swagger at work. For seven years, Hanna had led Bikini Kill, a band that inspired thousands of young women and fundamentally changed the gender dynamics of punk rock. But Bikini Kill, and the movement that they helped inspire, also became a reductive media talking point and a flashpoint for stupid controversies. Bikini Kill broke up in 1997 while they watched their whole narrative spin out of control, and Hanna did something completely different.

That different thing was Julie Ruin, the alter-ego that Hanna adapted in 1998. Under that name, she released a truly strange and fascinating album, a piece of electronic bedroom-pop in an era when electronic bedroom-pop was not just something you could knock out on a laptop. Hanna sang quietly, programmed beats, sampled the Clash and Foreigner. And then she got together with a few friends to try and figure out how to perform those songs live. Those live performances never happened. Instead, that band became an entirely new thing.

At the beginning of Le Tigre, Hanna's two bandmates -- the zine maker Johanna Fateman and the video artist Sadie Benning -- were not musicians. Or, at least, music wasn't their main focus. They recorded what would become Le Tigre on pieces of equipment that were new to them: drum machines, samplers, turntables, Farfisa organs. That means Le Tigre is a slapdash collage of an album, but it's also an album charged with a sense of discovery, of these three women figuring out what kinds of sounds they could make.

In an interview earlier this year, Hanna described the band's objective like this: "We want to write political pop songs and be the dance party after the protest." Nobody was trying to write political pop songs in 1999. On the DIY underground that Hanna had called home for years, nobody was trying to write pop songs at all. It wasn't something you did. Bikini Kill had always been deeply catchy; it was one of their secret weapons and one of the reasons that so many male punks regarded them with suspicion. But Le Tigre's embrace of '80s new wave sounds -- before electroclash, before dancepunk, before indie clubs hosting '80s dance nights -- was something new.

That comes together the most clearly and perfectly on "Deceptacon," the first song on Le Tigre and the best song that the band ever wrote. "Deceptacon" hit like a bomb. It took a nonsense chorus hook from a novelty oldie and a title from the bad robots on Transformers, repurposing them into a joyously derisive anthem, and that still triggers adrenaline.

"Deceptacon" sounds like Bikini Kill transformed. Hanna, one of the greatest bandleaders in punk history, kept her sneer fully intact, screaming put-downs at cluelessly self-confident assholes: "You bought a new van the first year of your band!" "You're so policy-free!" "You want what you want but you don't wanna be on your knees!" "Your lyrics are dumb like a linoleum floor!" "I'm so bored!" That's some cold shit, but when she howls it over a hyperactive surf-guitar riff and a rickety drum-machine thump and a smoke-alarm bleep of a synth-hook, it really does sound something like pop music, or at least a version of pop music that might exist in a better world.

But Le Tigre isn't an album about assholes. It's a half-hour affirmation, a whoop of encouragement. Three years before "Losing My Edge," "Hot Topic" shouts out friends and influences and heroes. And unlike James Murphy, Hanna and her friends aren't being sardonic; they're saluting fellow warriors. Some of the names named on that song are famous (Yoko Ono, Joan Jett), and some are less so (Cecelia Dougherty, Vaginal Creme Davis). But together, they represent a giving-a-fuck syllabus and also a worldview. Le Tigre's party is big enough to include Mia X and the Slits and Gertrude Stein and Billie Jean King, and the names you recognize make you want to look up the ones you don't. In an era before most of us even knew how to use Google, a song like this was both a banger and a valuable resource.

And the rest of Le Tigre is about joy and solidarity. The anger is there: "I went to your concert and I didn't feel anything!" But most of the album is a celebration. "Eau D’Bedroom Dancing" is a straight-up love song that takes place in a private world where nobody criticizes you. "Friendship Station" and "Les And Ray" are about relying on your people to get you through shitty times. "My My Metrocard" imagines New York as a whole world that you could explore for $1.50. (That last song is as much a relic of a dead-and-gone New York as, say, The French Connection is.) And even when Le Tigre are talking shit, they're being funny about it. Consider "Dude, Yr So Crazy!," a deadpan collection of phrases that, when taken together, paint a devastating portrait of a deluded chump: "So defeated. Thinks it's funny. Film festival. Retro porn."

That first Le Tigre album felt like a complete reimagining of what punk rock could be, of how it could feel. Le Tigre couldn't really follow it. Sadie Benning didn't want to tour, so she left the band, and their projectionist JD Samson took over for her. Le Tigre put out another album, 2001's Feminist Sweepstakes that captured the spirit and some of the power of the debut without really pushing the sound forward. Then they signed to a major label and made a pretty bad record, the 2004 buzzkill This Island. They produced an awkward Christina Aguilera song. They broke up and then got back together in 2016 to make a song that attempted to get out the vote for Hillary Clinton. These days, you can hear their music in ads for Pandora and Fruity Pebbles and Netflix movies -- all that unbound energy transformed into commerce.

And yet Le Tigre has aged remarkably well. On "What's Yr Take On Cassavetes?," they tried to puzzle out the question of how to deal with important but fucked-up art, a problem that we're all still attempting to reckon with now. On "My My Metrocard," they screamed out, "Oh, fuck Giuliani! He's such a fucking jerk!" Still true! The hooks are still massive. The joy and anger are still tangible. The sense of freedom still surges through the album. It's a cool record.