"From doing records from sampling, I started learning the science about what happened to soul music," the Alchemist told me 13 years ago. One evening, at New York's Baseline Studios, I sat in a backroom full of ancient, dusty records, and I listened to the Alchemist and Just Blaze talk about disco. The Alchemist's point, which Just Blaze enthusiastically seconded, was that R&B music had to change when disco came in. The old soul singers had to pivot to disco. And when soul music fully oriented itself to the club, something was lost.

This was the spring of 2006. Just Blaze and the Alchemist, both great rap producers, had been making huge hits a few years before. Just Blaze: "Oh Boy," "Roc The Mic," "What We Do," "Public Service Announcement (Interlude)," "Breathe," "Touch The Sky." Alchemist: "Keep It Thoro," "We Gonna Make It," "Got It Twisted," "Wet Wipes." These were big records. They were also products of the '90s New York mentality: Screaming samples, clattering drums, mean lyrics. And in the spring of 2006, songs like that were no longer hitting.

Just Blaze and the Alchemist had reason to stress about the dominance of club records. Club records were everywhere in 2006. A lot of fans of rap music blamed the ascendence of Southern rap, but it was bigger than that. It was the influence of A&Rs, the need for radio play, the idea that simple thump-thump-thump tracks were the way forward. To these guys, it was like what happened with R&B and disco in the '70s. They were not happy about it. Just Blaze and the Alchemist came from different places; Just Blaze is a black man from New Jersey, and the Alchemist is a white man from Beverly Hills. But they had similar aesthetics, similar values, and similar worries about where things were going.

They would go different directions. The Alchemist would turn toward underground music, hosting rap camps in his Los Angeles house, throwing Action Bronson on records with Earl Sweatshirt and vice versa. Just Blaze would make club records. He scored his first (and, to date, only) #1 hit with T.I.'s Rihanna collab "Live Your Life," building it on a sample of O-Zone's viral and deeply cheesy Euro-dance smash "Dragostea Din Tei." He made records with Eminem. He spent a lot of time DJing.

And at the dawn of the '10s, it looked like rap music was going exactly the way Just Blaze imagined and anticipated. Worse: It looked like a long-foretold prophecy had come to pass. In the early decades of rap's history, every enormously popular white rapper -- the Beastie Boys, Vanilla Ice, Eminem -- looked like a potential Elvis, a white crossover figure who seemed likely to take rap away from the black communities that had historically made the music. It never quite happened. But in the early '10s, it almost did.

Part of it was the club records, which became the bottle-service records. The Black Eyed Peas spent most of 2009 topping the charts with gleefully witless electro-rap stompers that never even got played on rap radio. Florida rappers like Flo Rida and Pitbull jumped on the wave, making music aimed at bottle-service bros, and they made huge chart impacts. Rap music was blurring and intermingling with a global club-music machine, and it was losing its identity in the process.

The first #1 single of the '10s was Ke$ha's "TiK ToK," a pretty fun song that grabbed rap and did whatever it wanted with the music. Ke$ha half-rapped about party-girl life over candy-floss synths, somehow gentrifying the Fergie sound. In the first half of the decade, most of rap's biggest hits were entirely dependent on that exultant, triumphant club-rap thunk. LMFAO, a duo of goonish Motown scions, presented themselves to the world as party clowns. B.o.B., who once seemed like a promising heir to the Dungeon Family's Atlanta art-rap flame, simpered his way to #1 with the gum-shriveling ballad "Nothin' On You." Worse, Macklemore and Iggy Azalea -- two artists with very different levels of pedigree and sincerity who were nevertheless received the same -- bubbled up onto pop radio and scared the hell out of people who cared about rap. By the mid-'10s, top-40 radio stations mostly weren't even playing black rappers. The Elvises had arrived.

Meanwhile, rap music was going through seismic ground-up changes, but they weren't happening anywhere near the pop charts. The Chicago teenager Chief Keef made singsong anthems out of bleak, traumatized nihilism. He became a viral hero, but Interscope dropped him after his debut album didn't do the numbers they wanted. Gucci Mane, during all the periods when he wasn't imprisoned, cranked out an unbroken stream of mixtapes that made lyrical balloon animals out of gun-talk threats. His young charge Waka Flocka Flame made outright fight music, catalyzing a rebirth of interest in old Memphis goth-stompers Three 6 Mafia (whose Juicy J went on to have a great little solo run) and popularizing the rap-show moshpit. Meek Mill yell-rapped about poverty and prison. Future gurgled about drugs. All of these rappers were enormously popular, but the music industry hadn't figured out how to monetize their impact. As far as the charts were concerned, they were negligible niche figures if they even existed.

And yet these undergrounds continued to churn. Sometimes, they pushed upwards and became impossible to ignore. Kendrick Lamar channeled the nervous, frantic energy of the old LA underground into virtuosic arena-sized anthems. The skate rats of the Odd Future crew filtered fatherless anxiety through edgelord provocation and Neptunes worship. Chance The Rapper yipped and yammered and hemmed and hawed and loved his grandmother. All of them were cult heroes long before being upstreamed into general-interest pop culture. All of them had defined aesthetics. All of them knew who they were. That mattered.

All those artists -- Chief Keef, Gucci Mane, Waka Flocka Flame, Meek Mill, Future, Kendrick Lamar, Odd Future, Chance The Rapper -- got their start making mixtapes. That was key. By making their own albums and uploading those albums to DatPiff without label involvement, they all presented themselves as fully formed entities. Even a crossover artist like Wiz Khalifa had his own mixtape-borne cult to fall back on. He played the industry game because he wanted to, not because he had to.

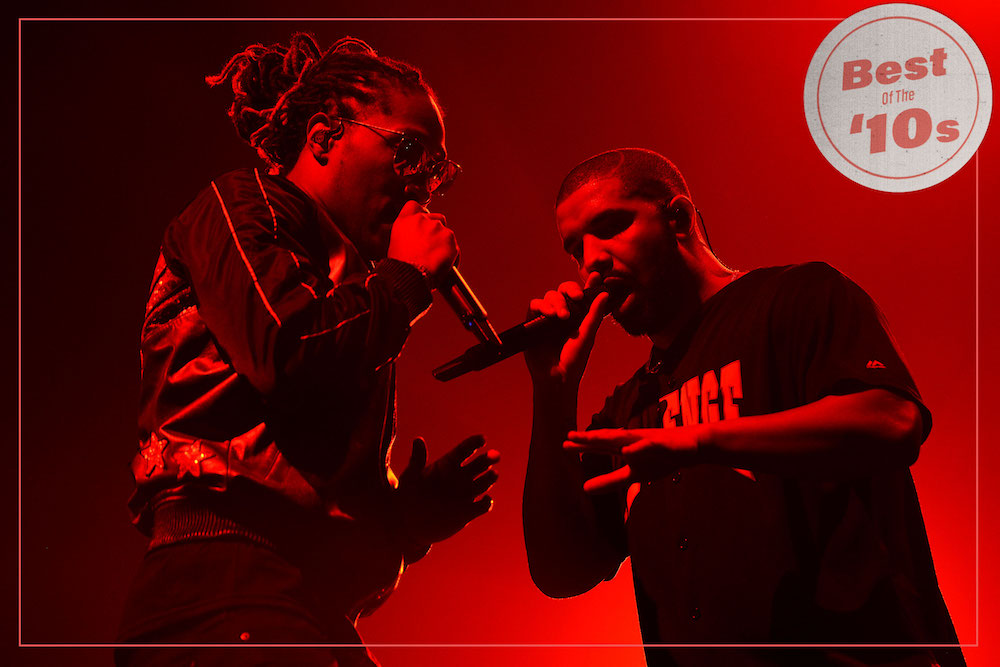

All of them lived in the shadow of Drake, the biggest new star of 2009. Drake had made the mixtape-to-mainstream transition before any of his generational peers, shoving his way onto pop radio while So Far Gone was still readily available on DatPiff. Through that first half of the decade, Drake played the game admirably. He made club records when he had to, but they never seemed obvious or forced. They drew on dancehall or bounce or old R&B, not superclub EDM. Drake maintained his connections to '00s stars like Lil Wayne and Rick Ross. He paid enough attention to the various online undergrounds that he always picked the right moment to, say, recruit A$AP Rocky and Kendrick Lamar as arena-tour openers. Drake established a lane for himself as a cool-kid pop star who could still flex when he wanted. He maintains that today. That's what makes him the defining pop star of the past decade.

Drake's entire career would've been unthinkable without the precedent of Kanye West, the defining superstar of the previous decade. West had established the idea that a mouthy, chatty, not-tough-at-all dork could be a transcendent rapper. Early on, West took Drake under his wing, directing his (terrible) "Best I Ever Had" video. Later on, they got into an endless cycle of cold-war feuds and reconciliations. But West couldn't hope to do what Drake did this decade. West made great records and big hits in the '10s, and his 2008 album 808s & Heartbreak proved to be a foundational influence on all the numb, Auto-Tuned blues-gurgles that followed. But in the past decade, West either played catchup to what rap was doing (as on great singles like "Mercy") or attempted to move the genre in directions that it did not want to go (see: Yeezus). West was no longer driving the cart. The cart was driving him.

Meanwhile Drake's fellow Young Money newcomer Nicki Minaj tried to do something similar to the elegantly adaptable Drake method. But that line's not as easy to walk, especially if you're a woman. As a woman in pop, Nicki had to make certain pop moves. As a pure rapper, Nicki was always far more talented than Drake, who never had anything like Nicki's "Monster" verse in him. But Nicki vacillated more wildly between her pop and hard-rap sides, a split that culminated at the 2012 edition of Hot 97's Summer Jam. Early in the day on an outdoor stage, the New York DJ Peter Rosenberg made dismissive allusions to Nicki's dance-pop songs and to her female fans. Nicki abruptly cancelled her headlining set, sending the station scrambling for last-second replacements. Nicki's frustration made sense. She was the dominant woman in rap music, and yet her career was held hostage by the question of how rap-music dominance should look and sound.

What finally settled that question was streaming. In that way, the pivotal rap album of the decade might be Drake's 2015 full-length If You're Reading This It's Too Late. Drake called that record a mixtape, and he originally planned to put it up as a free download, with DJ Drama yelling all over it. Instead, he released it for sale on iTunes and, more crucially, for streaming on Spotify. Two months earlier, Billboard had started including streaming in the calculations of its album charts. Four months later, Apple Music started.

If You're Reading This sold hundreds of thousands in its first week. It eventually went double platinum and ended 2015 as the year's #4 seller. This was a record conceived as a mixtape, with no attempted pop crossovers and no superclub thumps. With that album, Drake took over commercial dominance from Eminem, whose Marshall Mathers LP 2 had been the biggest rap seller of the previous year. The newly calculated Billboard charts now had reason to pay attention to products of the mixtape underground. And the people who made rap mixtapes mostly started releasing those mixtapes through label-endorsed channels. This music had always been popular. Now it was popular in ways that were Soundscan-verified. The climate had shifted -- even a no-budget, no-name viral star like Brooklyn's Bobby Shmurda could have an impact on the pop charts.

When streaming took over, funny things happened. Blurry, melodic drug-music -- music like the type Future and gibbering Gucci Mane protege Young Thug had been making -- turned out to be ideal streaming fodder, a soundtrack that could melt into the background as people went about their day. Soul-sick half-sung Auto-Tune laments became pop hits. And Atlanta trap, with its skittering hi-hats and warped hooks, became the new de facto sound of mainstream pop music, displacing the candy-coated club songs of the decade's first half. Rae Sremmurd and Migos, two Southern family acts, scored back-to-back #1 hits. Desiigner, a Brooklyn teenager who did everything possible to sound like Future, achieved one-hit glory after showing up on a Kanye West song. Post Malone bubbled up out of the ooze, a brain-fogged Macklemore for a new era.

That Atlanta trap thing, like the club-thump sound before it, eventually achieved oppressive omnipresence -- the same thing that, as Alchemist had noted, had once happened with disco. 808 bass tones came to dominate the mainstream, and they provoked their own angry reactions, like the lo-fi tantrums of 2017's SoundCloud-rap wave. And yet those sounds allowed rap music to reclaim its rightful place as the most popular form of music in the Western world. Rap arena tours and stadium-sized festivals proliferated. Rap-playlist placement came to matter a whole lot more than radio play. And Drake stood tall as a circa-now Frank Sinatra, a guy who surfed every wave and whose dominance never flagged, even though his biggest and most streaming-friendly hits were the ones where he barely even rapped a bar.

As rap has joined itself to the streaming economy, it's become more of a fully-online phenomenon. Internet-borne narratives are now prerequisites for rap stardom. Cardi B has lived out her entire relationship with Offset -- marriage, breakup, parenthood, the whole thing -- in the glare of her social-media feed. Travis Scott first found fame as a liquid, adaptable collaborator and then as an ancillary Kardashian. Kanye West clings to relevance because his constant, spectacular flame-outs make good internet. The narratives have merged with the music. They're inextricable.

At the same time, the music has taken on the same TMI-disclosure aspect as a teenager's Twitter feed. That's a good thing. Rappers discuss trauma and depression more readily than they ever have. They're more likely to present themselves as broken messes than as untouchable superheroes. These days, rappers rap more about using drugs -- real drugs, not just weed -- than selling them, something that would've been unthinkable at the end of the last decade. There's a self-destruction in rap that wasn't always there. It's led to a lot of deaths -- Mac Miller, XXXTentacion, Lil Peep -- and a lot of imprisonments and crushed careers. Bobby Shmurda has been in jail since a few weeks after he got famous. Tekashi 6ix9ine worked himself into a shoot, figuring that he'd be more bankable if he had an army of Bloods behind him and immediately destroying his own career. It's gotten messy. But that willingness to be messy has also made the music more liquid, more expressive.

Right now, rap music is a wide landscape, one with room for a lot of different sounds. True-school technicians like Kendrick Lamar and J. Cole, who might've been consigned to the underground in past decades, are now arena stars. Album-rap artiste types -- Danny Brown, Vince Staples, Run The Jewels -- have taken the same comfortable critics'-favorite slots that used to go to college-rock bands. Regional styles persist; the yammering post-hyphy sound of the California underground is especially exciting right now. And even the noisiest, most outré outlier has a shot to go at least a little bit mainstream. Alchemist and Just Blaze aren't making hits anymore, but both of them seem to be doing just fine. That's a beautiful story. Rap music has been the sound of young America for decades. But now, everybody knows it.