There is a well-worn yarn about Spoon's career. For years, the prevailing narrative was that you could barely create a narrative around them at all -- they were not part of any one indie era or scene, exactly, and they were just freakishly consistent. That was it; that was the whole story. Despite small modulations and a slow rising arc, the thing you could always say about each new Spoon album was that the songwriting was as smart and sharp as ever. Fans have their own favorites spread out across the catalog, and almost every one is the correct answer.

Then, 10 years ago this weekend, Transference arrived. It's the most divisive album in the band's career -- unless you count their early albums, which don't actually feel that divisive but more like a cult concern. Suddenly, it seemed to give people something to talk about with this ever reliable band.

Over time this is how the story shifted: Despite characteristically strong reviews, Transference would anecdotally be seen as a slight dip or disappointment. Maybe those reviews weren't quite as strong, maybe conversations with fellow fans struggled to make sense of the album. By the time They Want My Soul arrived in 2014, it gave us music journalists a thin narrative for this band at last: Now there was a comeback. Spoon was re-focused.

Amidst this, the mythology of Transference grew, with a certain contingent of hardcore Spoon fans who ride for Transference as a great under-heralded, misunderstood album. This became a theoretically contrarian take that was as cliché as reducing Spoon to “consistent” to begin with. For a band that's supposedly all about just being predictably really damn good, Transference became about as big a controversy as you could get in the world of Spoon.

The context of Transference's origins is crucial to the whole story surrounding it. After 2007's Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga, Spoon were as big as they'd ever been. Artistically, it represented the final destination, the ultimate refinement, of the sound they'd been digging into ever since beginning to come into their own with Girls Can Tell in 2000. It was an impeccably crafted indie album, all of Spoon's grooves and hooks amplified and polished just so. It resulted in more ubiquitous songs, a success story in an era when indie was beginning to cross over to a new form of mainstream penetration driven by festival appearances and the right movie syncs. It hit the top 10 on Billboard's album charts, and suddenly this journeyman group was in a position where their steadiness could propel them further up the ladder than previously expected. Transference, in response, was something like pressing a self-destruct button.

Spoon wanted to do something different. They knew they could make another Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga, but the goal wasn't to just repeat that sound and that kind of success. (It bears pointing out that even in their '00s indie ascension, each Spoon record is distinct from the others; there are plenty of consistent tricks and tropes, but each album has more of its own identity than the band was often given credit for.) When I spoke to frontman Britt Daniel last year, he reflected on that time period, saying:

We kinda just couldn’t believe how big things had gotten with Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga. We couldn’t believe how successful it was. We loved it, we loved the ride. But we didn’t want to keep making the same record over and over again. We had made four records with Mike McCarthy, from Girls Can Tell to Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga. We knew we could do that. We knew if we did that it would turn out to be a certain type of record. We could make it good if we put enough effort into it, but we wanted to, you know, try something else.

The band considered a couple routes. They talked to none other than Mark Ronson about producing, getting as far as sending him early iterations of "Trouble Comes Running" and "Written In Reverse." But Spoon grew impatient with Ronson's packed schedule and decided to just produce it themselves. As a result, a lot of Transference was recorded by Daniel solo at his home in Portland; about half of the album remains in demo form.

Though Transference isn't without its sonic affectations and new ideas, this gave it the feeling of an altogether dirtier, scrappier version of Spoon. You could take it as almost a direct refutation of the version of Spoon that had existed on Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga, as if the band was pulling the old-school indie move of torpedoing burgeoning mainstream attention.

The end result was still recognizably Spoon, but almost like a Mr. Hyde mutation. Daniel himself has called the album "uglier," both upon its release and when revisiting the album in more recent interviews. In its rawness, there's a whole different subtext to Transference, likely part of what has split fans over the years: While still as finely and carefully realized as any of their work, Transference also sounds like Spoon actively deconstructing the sound and identity that drew people to them over the preceding decade.

The album starts off with a song that almost makes this explicit in theme and form. "Before Destruction" sounds like a Spoon song collapsing, or sputtering to life, in real time. Jim Eno -- a pivotal element to the band and to transformations like this album, as the drummer and the sole original member alongside Daniel -- provides a beat that sounds like a sort of slowed-down, haggard descendant of the insistent rhythms with which he'd usually propel the band. Daniel's voice, when it enters, is cracked, then smeared and echoing. All the usual colors are there, but the band is muddying them, distorting them.

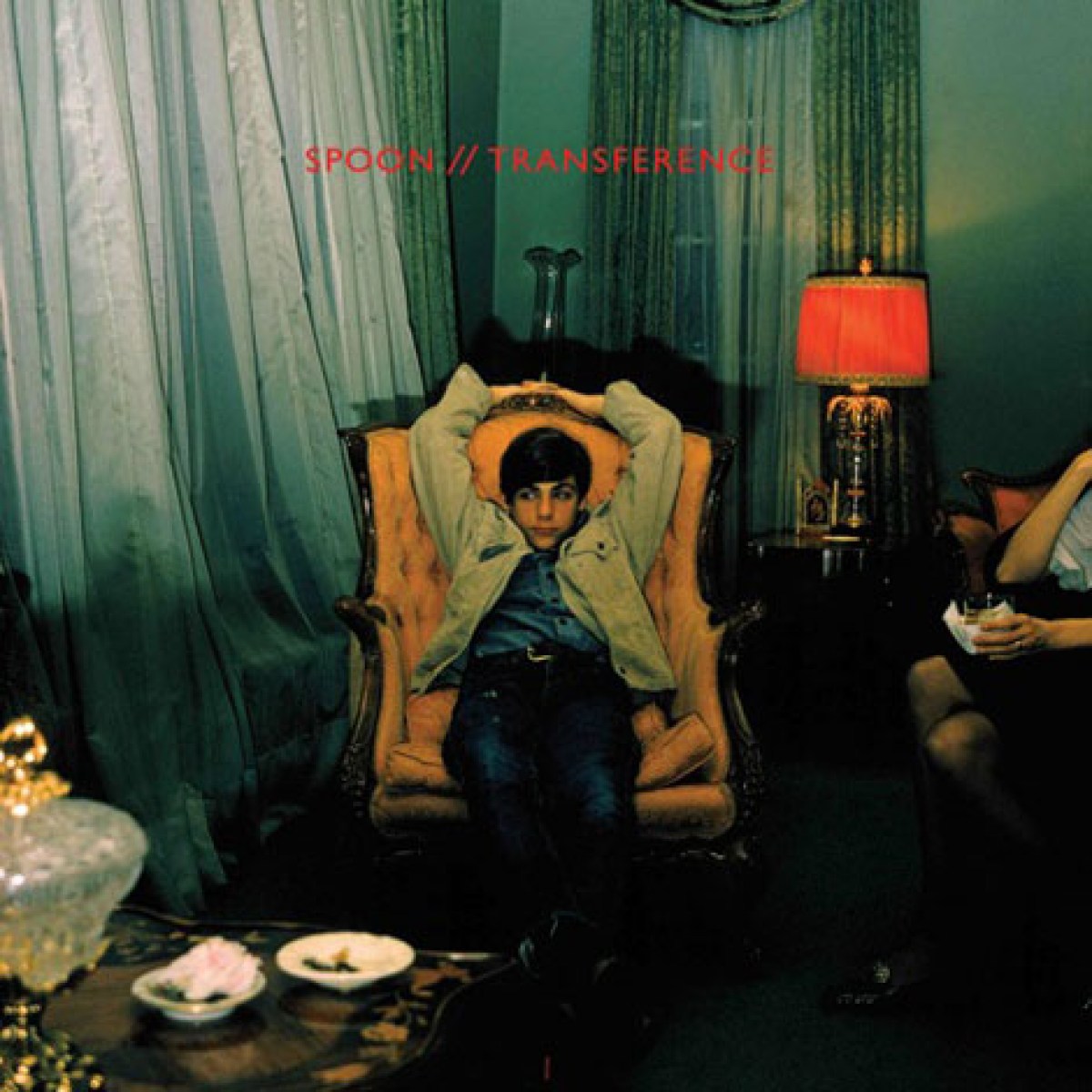

Right after, "Is Love Forever" takes a similar approach, and a lot of Transference follows suit: Spoon songs, but fragmented. None of it is quite lo-fi, but songs like "Written In Reverse" and "Trouble Comes Running" represent what happens when the usually precise sculpting of a Spoon song is allowed to become ramshackle. "Goodnight Laura" is a piano ballad, left unadorned and dusty, as if Daniel is playing it in the corner of the room captured in the '70s William Eggleston photo on Transference's cover. And elsewhere, they allow themselves to sprawl out, unspooling "I Saw The Light" and "Out Go The Lights" into languid, bleary-eyed jams.

Expansion wasn't only relegated to the confines of particular tracks. While Transference might be overwhelmingly remembered as the scraggliest Spoon album, the synth flourishes on "The Mystery Zone," the rubbery funk of closer "Nobody Gets Me But You," and the floaty haze of "Who Makes Your Money" both presaged a 2010s in which Spoon would experiment with their sound more than ever before. Each remains a highlight from Transference, alongside "Got Nuffin." The lingering calling card for Transference -- despite arriving half a year earlier via its own EP -- "Got Nuffin" is the quintessential Spoon song of the bunch, the one that feels like it could've been on most other Spoon albums, the one that sounds like an instant-classic Spoon song the first time you hear it, even as the lean muscle and mean swagger keep it within the world of Transference.

This is what's caused the album to be such a flashpoint in Spoon's career. There might've been outliers and stylistic detours on previous Spoon albums, but the looseness of Transference is a sonic detail as well as a thematic one -- it is pushing and pulling, a band fighting against themselves and just maybe figuring out something new in the process. You could just as easily regard it as a beleaguered post-script to the bulletproof run they had through the '00s, or a prologue to a more searching '10s. It's a transitional work following up perhaps their signature album, and that's always going to leave questions and murkiness in its wake.

Spoon's most broken-down songs happened to coincide with a breaking point in Spoon itself. The tour supporting Transference became grueling. By the end, the band was reportedly not getting along well, feeling deflated. It yielded a four-and-a-half-year wait for They Want My Soul, the longest gap between Spoon albums to date. In the years since, Transference material has only made sporadic and temporary appearances on Spoon's setlists, save "Got Nuffin," which was also the sole Transference cut included on Spoon's best-of collection Everything Hits At Once when it was released last year.

When Daniel's discussed the album in recent years, it's hard to pin him down -- it sort of sounds like something he doesn't totally regret doing, but something he doesn't especially like. Speaking to Pitchfork last year, he recalled that after Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga, he thought "Spoon was going to keep going up and up and up -- and in terms of selling tickets, it has. I knew Transference was an uglier record that didn't have as many hits on it, but I still thought everybody that bought Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga was going to buy it. I wasn't exactly right. I don't think we failed on that record, but it did turn a lot of people off." He told me something similar in our interview: "I’m glad we did it. It was maybe not the wisest career move."

The fact that Daniel more or less depicts the album as a self-inflicted wound and a necessary growing pain simultaneously is telling. Maybe it was self-sabotage, restlessness, or creative upheaval. Whatever spurred it, the messiness of Transference scans differently now, 10 years later and on the other side of two more albums. No longer is it purely the complicated successor in the long shadow of Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga's success. As a transition, it wound up drawing a line in the sand: This was the move from Spoon's laser-focused '00s towards an altogether artier, more exploratory '10s.

In hindsight, Transference feels as if it forms an unofficial trilogy of nocturnal city albums with They Want My Soul and Hot Thoughts. They Want My Soul is the lush, romantic one, unfolding on rain-slicked streets under streetlights; Hot Thoughts is the trippy plastic funk shot through with the lurid colors of a seedier, imagined metropolis. Transference is a sort of bleaker beginning to the arc, the roughened, drunken amble into a listless, decrepit evening. Each album is almost totally different, and yet you don't really get to the gorgeous redemption of They Want My Soul or the neon adventurousness of Hot Thoughts without the restart-as-implosion of Transference.

The answers about whether Transference was wrongfully criticized or wrongfully used as a straw man in the whole story of Spoon's catalog, about whether it's underrated or overrated, or about whether it's a typical Spoon album more sloppily made or a conscious dissection of their formula, are not any easier to settle on 10 years later. For as long as Spoon continue at the clip they've maintained the past 20 years, there will be Spoon fans who are acolytes of one particular iteration of the band or another. Transference might not seem as glaring or deliberate of a sidestep as it did in the immediate aftermath of Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga back then, but the distance between different fans' outlooks, the distance between critical narratives and listener infatuations, will probably fluctuate more so than it will ever close completely.

This, in the end, is the beauty of the consistency cliché that surrounds and oversimplifies Spoon's career. Maybe you find the back and forth about this album passé at this point. Maybe you have moved on to new contrarian Spoon takes, like They Want My Soul is a classic on the level of their more readily-denoted classics from the '00s. (This is a very justifiable take, by the way.) Maybe you are still talking about Transference now. Maybe it's your favorite Spoon album, and the person you're talking with thinks you are insane and asks how could you possibly say that when Kill The Moonlight and Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga exist. But that's the way it's always going to be with this band, because if there's anything that seems certain 10 years removed from Transference, it's that this band doesn't make bad albums.