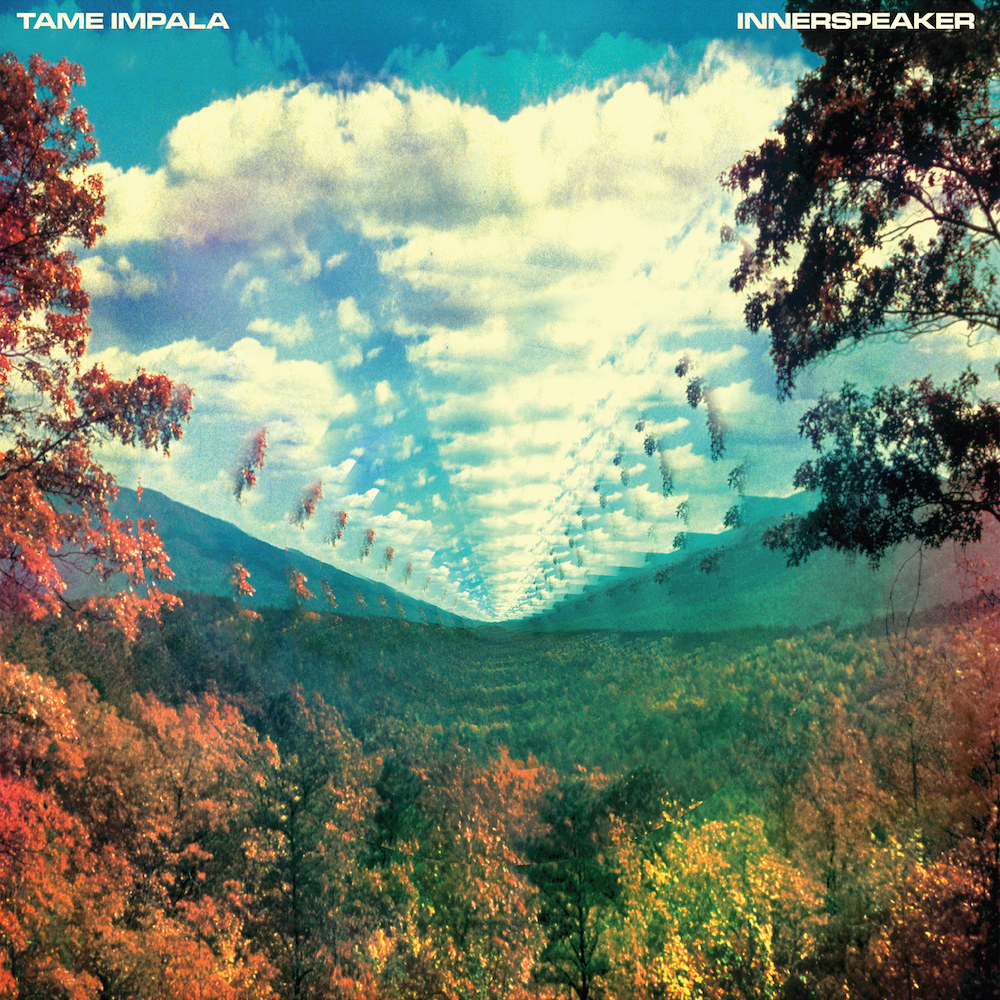

Before Kevin Parker could write psychedelic rock's future, he had to rewrite its past.

Nowadays the world knows Tame Impala as one of the defining rock bands of the 2010s and Parker as the loner studio genius who set the trajectory for modern psych-pop. He's the guy who voyaged through his LCD screen and across dimensions with Lonerism, who conquered the festival scene with EDM-infused classic rock anthems on Currents, who retrofitted Studio 54 party jams into "psychedelia for people with meditation apps and vape pens" on The Slow Rush. He's your favorite pop star's favorite rock star, the guy A-list rappers call to inject their projects with a hallucinatory DayGlo edge. To set the stage for all that, he blurred together loads of '60s and '70s classics into one of the sickest guitar albums of his era, a retro-futuristic launchpad for a remarkable career.

[articleembed id="2085248" title="Kevin Parker Looks Back" image="2085252" excerpt="The Tame Impala mastermind reflects on InnerSpeaker's anniversary."]

When InnerSpeaker came out 10 years ago today, no one yet understood how high Tame Impala would fly or how broad their reach would become, but people instantly recognized the album as something special. "It's difficult to be so plugged-in to a vintage feel without the music seeming time-capsuled, but the band's vibrance helps these songs sound very much alive," Pitchfork's Zach Kelly wrote, bestowing the album with Best New Music honors. The BBC raved, "InnerSpeaker has none of the predictable trappings of a modern-day psych record and liquid ambience aplenty." All Music Guide's 4.5-star review began, "The limpid lysergic swirls and squalling fuzz-toned riffs that populate Tame Impala's debut clearly owe a hefty, heartfelt debt to the hazy churn of late-'60s/early-'70s psych rock, but the members of this Perth threesome are hardly strict revivalists."

The word "threesome" presumably referred to Parker plus Jay Watson and Dominic Simper, who made minor contributions during the recording sessions at Wave House, a home studio overlooking the Indian Ocean in Injidup, about four hours outside Perth. Tim Holmes from Death In Vegas was also there to provide some "invaluable" help with engineering. Yet even back then, Tame Impala was really a Parker solo project, one man's kaleidoscopic vision emerging from an isolated metropolis on Australia's western coastline. InnerSpeaker was practically an album about the joy of solitary creation: "[The title is] kind of just a silly term I came up with to try to explain the feeling you get when you're at your most inspired," he told The Quietus, "the idea that it just appears to you vividly and if someone plugged a stereo into your brain they'd be able to hear it." Parker was skeptical that such a transfer of imagination was even possible -- on the pointedly titled lead single "Solitude Is Bliss," he famously declared, "You will never come close to how I feel" -- but InnerSpeaker sure felt like a direct pipeline from his brain to ours. If anything was lost in translation, the experience was still plenty vivid for those on the receiving end.

From the loopy awakening "It Is Not Meant To Be" to the speeding-off-into-the-sunset closer "I Don't Really Mind," the songs on InnerSpeaker are uniformly great. Any one of them could feasibly be singled out as highlights in Parker's discography, yet their power is exponentially greater as a unified whole. Like all Tame Impala albums, this one works best as an extended suite to get lost in. "We kind of just wanted to make it dreamy enough so you’re in the dream-pop realm, but still kind of a little bit gritty and rhythmic," Parker told Interview. "Groovy and pulsing, but at the same time kind of lo-fi and rough." Pushing his digital equipment into the red until it sounded analog, Parker conjured up a hard-hitting fantasia that felt familiar and brand new all at once. With a tracklist this stacked, it could have also passed for a greatest hits collection from some long-forgotten giants of psych.

There were no obvious singles because they're all obvious singles. The crunching groove of "Desire Be Desire Go," the turbulent undercurrent of "Lucidity," the intense bombardment of "Expectation" -- Parker's obsession with rhythm was already paying major dividends long before he started messing around with drum machines. Whereas "Why Won't You Make Up Your Mind?" crept up on you, building from a gentle pulse to an overwhelming surge, "Alter Ego" was a joyride from the get-go, like being cut loose to careen downward from precipitous heights. "The Bold Arrow Of Time" segued from a bluesy stomp to a prog synth reverie, as if Parker's record collection was melting together. There were traces of Hendrix and Cream, Sabbath and Hawkwind, King Crimson and MC5. Yet Parker's voice, with its uncanny resemblance to John Lennon, infused these lengthy excursions with a potent pop accessibility. The spiraling guitar riffs, the crashing drum loops, the fluid bass lines, Parker's holographic melodies -- all of it coalesced into sonic scenery as endless as the horizon. It was an invitation to turn off your mind, relax, and float downstream, but at the rough-and-tumble speed of a whitewater rafting trip that keeps plunging over waterfalls.

Some of the album's visceral impact can be credited to Dave Fridmann, who applied his legendarily loud touch to InnerSpeaker's mixing job. The involvement of Fridmann, who had worked closely with the Flaming Lips for years and produced MGMT's smash hit debut album Oracular Spectacular, instantly connected Tame Impala to their immediate forebears in psych-pop crossover stardom. Yet despite InnerSpeaker's jammy inclinations, Parker was never as willfully quirky as those bands. This much was clear watching Tame Impala open for MGMT just after Congratulations dropped. Whereas Andrew VanWyngarden and Ben Goldwasser were working overtime to challenge an audience who'd fallen in love with "Kids," Parker's crew was making this vast, exploratory music hit like pop. They would not be an opening act for long.