Welcome to the Number Ones Bonus Tracks, the addendum to our regular Number Ones column. We at Stereogum recently wrapped up our fundraising campaign, and we'd like to thank everyone who donated to support this site and keep it going. To those All Access donors who pledged $1,000, I promised that I'd write a Number Ones-style column on a song of their choosing, as long as that song charted on the Billboard Hot 100. We'll publish those once a week for the next couple of weeks.

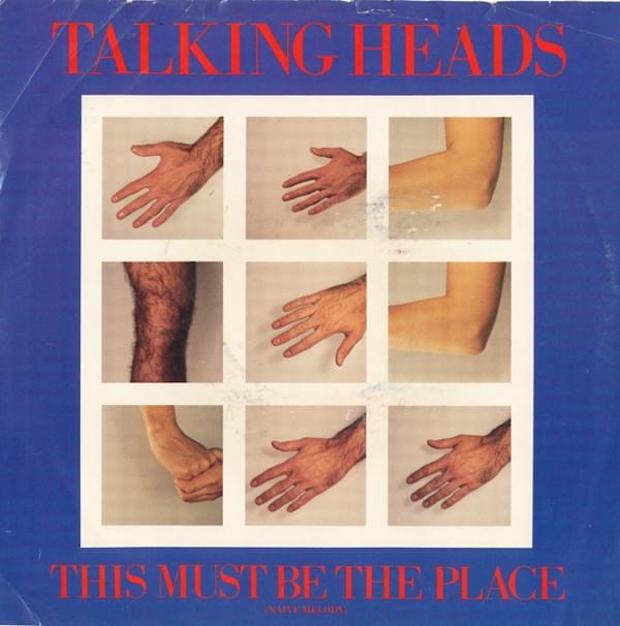

PEAKED: #62 on December 17, 1983

SONG AT #1 THAT WEEK: Paul McCartney & Michael Jackson - "Say Say Say"

This column is at the request of Stereogum donor Jimmie Manning. Here's what he wrote about it:

While “This Must Be The Place (Naïve Melody)” is one of my top-3 all-time favorite songs (the other two, Prince’s “When Doves Cry” and Madonna’s “Like A Prayer,” went to #1 and were/will be covered in this column), my reasons for picking it are purely romantic and sentimental.

My fiancé Adam and I were enjoying a long engagement. A very long, 3-year plus engagement. Both of us were busy establishing our careers and were already living together -- and, quite frankly, as a gay couple didn’t feel the heteronormative pressure that many others do.

Our relaxed attitude toward marriage changed on February 17, 2018. Adam’s mom, Rosie, called with bad news. She told us that the treatment she was receiving for her cancer wasn’t going as hoped, and she only had a few months to live.

Now Rosie wasn’t a Talking Heads fan. At all. She had a very limited range of music she liked, all from the same time period. Her favorites were Linda Ronstadt (sorry, Tom, but “You’re No Good” is a 10), Carole King, and James Taylor. Despite her generally soft musical tastes, though, she was loud, bold, and always had opinions.

And so it was no surprise to us that, in the face of death, she told us that our time to be engaged was over. She expected to see her son get married before she left this earth, and so Adam and I needed to get started on a wedding.

We got everything together in five weeks, even with Adam working many night shifts as part of his nephrology fellowship, a big job interview for me, and my Grandma passing away two weeks before the wedding. (My Grandma’s favorite song was “He’s Still Working on Me” by the Cathedrals. It went nowhere near the Hot 100.)

The wedding was beautiful, intimate, and simultaneously sad and joyous. We held it in the house where Adam grew up, and our closest friends and family joined us for the ceremony. Our wedding soundtrack included Stevie Wonder, Kacey Musgraves, Pearl Jam, Maxwell, Sturgill Simpson, and Janet Jackson, among others, and we walked down the aisle to Dolly Parton.

We wrote our own vows, and as part of mine I admitted that I never thought I’d actually be getting married. Growing up in Western Kansas in the 1980s and early '90s, being gay was something of a dead end. No one I saw or knew was gay, and this was before there were many TV shows or movies that showed what a queer life could be. Back then, I figured that I would suppress that part of my self and be alone. I would just stand it, as best I could.

Then, as I found who I was and my activist side emerged, my attitude changed from “just standing it” in the closet to being out, proud, and wanting absolutely nothing to do with marriage. “Let the straight people have it,” I thought. “Who needs a government or even a church to tell them that their relationship is real?”

But Adam changed all of that, as somehow his sweet and optimistic nature cracked through my cynical facade and we created a home and shared our dreams and, eventually, it was me who proposed to him. The night before the wedding, I was sitting on a laptop in my hotel lobby trying to find the words to tell him how he changed my worldview on love and marital commitment and how, maybe for the first time in my life, I had someone who really gave me the sense that I was part of a safe, caring, and loving home. And while I was struggling about how to say this, “This Must Be The Place” started playing over the loudspeaker; and I realized the words I was looking for were always there:

Home, is where I want to be

But I guess I'm already there

I come home, she lifted up her wings

I guess that this must be the placeWhen I read the lyrics as part of the vows, my 5-year old nephew blurted out, “Oh my! That’s beautiful!” I’m glad kids who are growing up now get to see that all forms of love are valid, precious, and worthy of dignity.

Rosie passed away two months after the wedding. She was resting in her own bed, just as she wanted. Adam was too heartbroken to be by her side, so I stayed in the room and held her hand as my father-in-law and her nurse told her it was okay to go.

The last gift she gave us, the nudge into marriage, continues on; and much like the affect created by this song, it feels as if this love is a fortunate happy accident, a mix of the extraordinary and the mundane.

Talking Heads songs prior to “This Must Be The Place” were certainly brilliant, and they forever changed the face of popular music; but, much like me, the group’s music never really surrendered to love. That changed with “Place,” where the careful artifice and affect of their past records gave way to warm synths, chirpy guitars, andunabashedly romantic lyrics sang wildly and from the heart by David Byrne.

It is the way that this song has for me, like it has for so many others, continued to conjure up the sense of closeness, warmth, messiness, and gratitude that I pick it for my bonus The Number Ones column. And I dedicate this pick to my sweet husband Adam who taught me the kind of love this song represents.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=pVrVY540xdc&ab_channel=sarsamis

David Byrne was in love. This was weird. According to at least some accounts, Byrne was a cold, awkward, remote human being who somehow built a wildly engaging stage persona out of his own cold, awkward remoteness. Byrne's own ex-bandmate Tina Weymouth has accused him of being "incapable of returning friendship."

Byrne's band Talking Heads had called their second album More Songs About Buildings And Food, and the matter-of-fact mundane specificity was the whole point. Talking Heads didn't make pop music, and they never aimed for the kind of chart domination that their old CBGB peers in Blondie achieved. Talking Heads made songs about buildings and food -- or about murderers and survival scenarios and puzzled middle-class alienation. They didn't really make love songs. But then David Byrne fell in love, and they made one.

"This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)" is a strange and lovely hymn of a song that appears right at the end of Speaking In Tongues, the first Talking Heads album that could really be considered a hit. Before Speaking In Tongues, Talking Heads were an intellectual art-kid sensation -- the kind of band that inspires religious devotion in a small core but doesn't really threaten to break out of that. By Speaking In Tongues, though, the group had dug deep into a stiff, jittery rhythmic zone -- one that saw no real borders between deep funk and art-rock. Almost by accident, the group had become a commercial proposition.

Speaking In Tongues was Talking Heads' first platinum album, and the LP's lead single, the opening track "Burning Down The House," was their one and only top-10 hit. ("Burning Down The House" peaked at #9. It's a 9.) Live, the band expanded to a huge ensemble, one that roped in musicians as varied as King Crimson's Adrian Belew and Parliament-Funkadelic's Bernie Worrell. While touring behind the album, the group got together with director Jonathan Demme and made Stop Making Sense, the greatest concert film of all time.

Most of Speaking In Tongues is the Talking Heads' take on nervous club music, and it arrived at a moment when nervous club music was in the zeitgeist, which led to Talking Heads getting actual nightclub play with that. But "This Must Be The Place" is the one Speaking In Tongues track that diverges wildly from all that -- that creates its own strange and placid little world. Decades later, it's the Speaking In Tongues track that's resonated the longest.

By time the Talking Heads came out with Speaking In Tongues, they'd been a band for the better part of a decade. Byrne, born in Scotland, had mostly grown up in the Baltimore suburb of Arbutus. I've never really heard Byrne talking about being from Baltimore, but Baltimore absolutely claims him. I spent a decent chunk of the early '00s at a since-demolished Baltimore club called the Talking Head. Once, when working at the Knitting Factory in New York, I sold Byrne a ticket to a Marc Ribot show and tried to talk to him about where he went to high school. (I have been told that Baltimore natives are weirdly fixated on discussing where we all went to high school.) This didn't seem to be a conversation that Byrne was that interested in having. I don't blame him.

Byrne studied art at the Rhode Island School Of Design, and while he was there, he got together with the drummer Chris Frantz to form a band that, hilariously, was called the Artistics. After graduation, Byrne moved to New York, and Frantz and his girlfriend and future wife Tina Weymouth arrived soon after. Byrne and Frantz wanted to start another band, but they couldn't find a bass player, so Byrne taught Weymouth to play bass. After the Talking Heads had become a band, Byrne reportedly made Weymouth audition a few more times.

Talking Heads played their first show in 1975 -- opening for the Ramones at CBGB, an incredible case of right place/right time. (The Ramones' highest-charting single, 1977's "Rockaway Beach," peaked at #66.) Sire signed the Talking Heads in 1976, and they released their debut album a year later. Their first single to chart was 1977's "Psycho Killer," but that only made it to #92. That same year, the multi-instrumentalist and former Modern Lover Jerry Harrison quit architecture school at Harvard to become the fourth Talking Head.

As time went on, the group's arch, rigid sound grew stranger and looser, especially under the influence of producer Brian Eno. Eno, who got along great with Byrne and not so well with the rest of the band, worked with Talking Heads on three albums, all of them stone-cold classics. Eno pushed the band toward deeper beats and headier atmosphere, but he did not turn them into hitmakers. For a long time, Talking Heads' only real chart hit was their 1978 version of Al Green's "Take Me To The River," which peaked at #26. (Eno will eventually appear in The Number Ones as a producer.)

After the Eno-produced 1980 masterpiece Remain In Light, Talking Heads went nearly three years without releasing an album, a rarity in a time when album cycles were shorter. There were side projects. Byrne and Eno made the lovely, experimental, sample-heavy 1981 album My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts. Harrison made a solo album, 1981's The Red And The Black. Weymouth and Frantz started the rap-adjacent group Tom Tom Club, and their 1981 single "Genius Of Love" peaked at #31. (It'll eventually appear in The Number Ones -- and in The Number Ones Bonus Tracks -- in sampled form.) All the while, Talking Heads toured and worked on ideas for Speaking In Tongues, an album that they produced themselves.

"This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)" started off as just "Naive Melody." Like a lot of other Talking Heads songs, it was an experiment. The band recorded the track at Compass Point Studios in the Bahamas, and most of the group tried playing instruments that they didn't ordinarily play -- Byrne on keyboard, Weymouth on guitar, Harrison on synth-bass. They brought in session synth specialist Wally Badarou, who'd previously played on "Pop Muzik," M's #1 hit from 1979. Together, they came up with a strange, repetitive, hypnotic groove -- a bloopy and comforting post-disco lullaby.

There's a remarkable amount of space in "This Must Be The Place." A lot happens on the song. There's a skittery guitar that recalls the Afrobeat that the band loved and a wobbly synth figure that reminds me a little bit of Hawaiian slack-key guitar. Some of the percussion sounds like bottles clinking together. Some of the synths sound a bit like the playful future-funk of "Genius Of Love." On much of Speaking In Tongues, Talking Heads are fully locked-in. On "This Must Be The Place," they sound like they're tiptoeing.

Throughout, Byrne sings softly -- an affectionate quaver that never loses its nervousness. His vocals are mostly chanty incantations, and he mostly leaves it to the groove to carry the melody. But at the end of the song, he hits one utterly devastating falsetto note. Byrne sounds faintly terrified on nearly every Talking Heads song, but on "This Must Be The Place," he allows some starry-eyed fondness to creep his way in. He sounds like a newly sentient robot who is just starting to discover the idea of happiness, and who seems to be at least a little bit afraid of it.

Depending on who you ask, that's not too far from what was happening in Byrne's life. Byrne had been in a relationship with the choreographer Twyla Tharp, but they'd broken up, and he'd met the costume designer Adelle Lutz while on tour in Japan. They would marry in 1987, have a daughter in 1989, and divorce in 2004.

On "This Must Be The Place," Byrne seems to approach the idea of both love and love songs with an exploratory sort of anxiety. He does not trust this feeling entirely: "I feel numb, born with a weak heart/ I guess I must be having fun." But he also sings about the terrifying, liberating feeling of figuring out how to be with someone, of making it up as you go along. And Byrne also gives the sense that he's starting to realize domestic bliss isn't necessarily just a bourgeois myth: "Hi-yo, I got plenty of time/ Hi-yo, you got light in your eyes/ And you're standing here beside me/ I love the passing of time."

In its own way, "This Must Be The Place" is a terribly romantic song. Even as Byrne reminds himself that this feeling might not last forever, he still allows himself the solace of it: "I'm just an animal looking for a home, and/ Share the same space for a minute or two." And he never stops being weird about it: "Sing into my mouth."

"This Must Be The Place" was the second single from Speaking In Tongues, and I can't imagine that anyone was surprised when it stalled out in the bottom half of the Hot 100. The end of 1983 was a great time for white people making twitchy dance-funk. The week that "This Must Be The Place" hit its chart apex, tracks like Hall and Oates' "Say It Isn't So," Duran Duran's "Union Of The Snake," and Yes' "Owner Of A Lonely Heart" were all in the top 10. Re-Flex's "The Politics Of Dancing" occupied the Hot 100 spot just above "This Must Be The Place." ("The Politics Of Dancing" peaked at #24.) But those songs are still pop music. "This Must Be The Place" works on a different plane of existence.

In the music video for "The Must Be The Place," Byrne directed the band -- the massive Stop Making Sense touring lineup of the band -- as they have implausible amounts of fun while watching screen-projected home movies and then play together in a basement. Adelle Lutz does the costumes, and Byrne shows a bit of the singular stage presence that would soon make him a cinematic icon in Stop Making Sense. But it's not a glamorous video, and it's way more of an art piece than most of what was on MTV at the time.

The same month that "This Must Be The Place" peaked, Talking Heads taped Stop Making Sense in Los Angeles with Jonathan Demme. In a short that was intended to promote the film, Byrne interviewed himself in split-screen. (He did part of the interview in blackface, and he just apologized for that last month.) In that self-interview, Byrne uses an affected monotone and responds to a question about why he doesn't write love songs: "I try to write about small things: Paper, animals, a house. Love is kind of big. I have written a love song, though. In this film, I sing it to a lamp."

Ah, yes. The lamp. Stop Making Sense is full of showstopping moments, but the best-remembered of all of them -- even more than the big suit -- is the part where Byrne sings "This Must Be The Place" while dancing with a floor lamp. It's oddly graceful. That lamp has been sitting up on the stage, next to him, for most of the song. He's been still. But then he turkey-struts over to the lamp, pushes it over, pulls it back, looking utterly entranced as its light falls on his face. When he finishes, he backs away, amazed, like he can't believe this wondrous thing is still standing. It's a perfect little piece of absurdist theatre.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=JccW-mLdNe0&ab_channel=RobinGlass

Stop Making Sense was a pretty big deal at the time -- big enough, anyway, to nearly quintuple its million-dollar budget and to help juice up Demme's directing career. The soundtrack sold two million copies -- Talking Heads' first time going double platinum. Their next album, 1985's Little Creatures, would also sell two million. But the band's internal tensions were already getting to be too much. Stop Making Sense shows the band as an utterly joyous live-show machine, but they quit touring after finishing the Speaking In Tongues cycle.

Byrne finally dissolved the band in 1991; Frantz learned about the breakup when he read about it in a newspaper. The other three members of the band have been intermittently active together since then, though Byrne hasn't let them use the Talking Heads name. He's also refused to brook any talk of a reunion. Talking Heads did play three songs together at their Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame induction in 2002, but that's been their only show since 1984.

Byrne has, of course, achieved the same beloved elder-god weirdo status as, for instance, David Lynch. Byrne is always out doing things, and since he's such a tremendously recognizable figure -- even more so, since he let his hair go bright white -- he's always easy to spot in New York. (This makes him vulnerable to freaks who want to ask him about his fucking high school.) Last year, Byrne staged a Broadway show, and Spike Lee filmed it. The result is the concert film David Byrne's American Utopia, which went up on HBO Max last week. It shows Byrne as a warmer, friendlier figure -- one who seems a whole lot less cold and remote and awkward. It no longer seems so far-fetched to imagine David Byrne in love. But when "This Must Be The Place" makes its appearance in American Utopia, it can still wreck you with all its unlikely beauty.

GRADE: 10/10

BONUS BEATS: In his 1987 movie Wall Street, Oliver Stone uses "This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)" to soundtrack a scene of Charlie Sheen fixing up his cold, yuppified New York apartment. Here's that part:

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the soft, lovely acoustic version of "This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)" that Shawn Colvin included on her 1994 album Cover Girl:

(Shawn Colvin's highest-charting single is 1997's "Sunny Came Home," which peaked at #7. It's a 7.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's video of a very, very young MGMT covering "This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)" on what I assume to be a Wesleyan quad sometime in the early '00s:

(As lead artists, MGMT's highest-charting single is 2008's "Kids," which peaked at #91. As guests, their highest-charting single is Kid Cudi's 2010 track "Pursuit Of Happiness," which peaked at #59.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Arcade Fire released a cover of "This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)" as a B-side in 2005, and David Byrne sang backup on it. Here's that version:

(Arcade Fire's highest-charting single is 2013's "Reflektor," which peaked at #99.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: "This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)" inspired the title of Paolo Sorrentino's 2011 film This Must Be The Place, in which Sean Penn plays a fading rock star. Byrne makes an extended cameo in the film, singing "This Must Be The Place (Naive Melody)" in its entirety while Penn, near tears, watches from the crowd. Here's that scene:

And here's the bit where Penn corrects a kid who thinks "This Must Be The Place" is an Arcade Fire song:

Thanks, Jimmie!

https://twitter.com/aliciacamden/status/1254453998163296256?lang=en