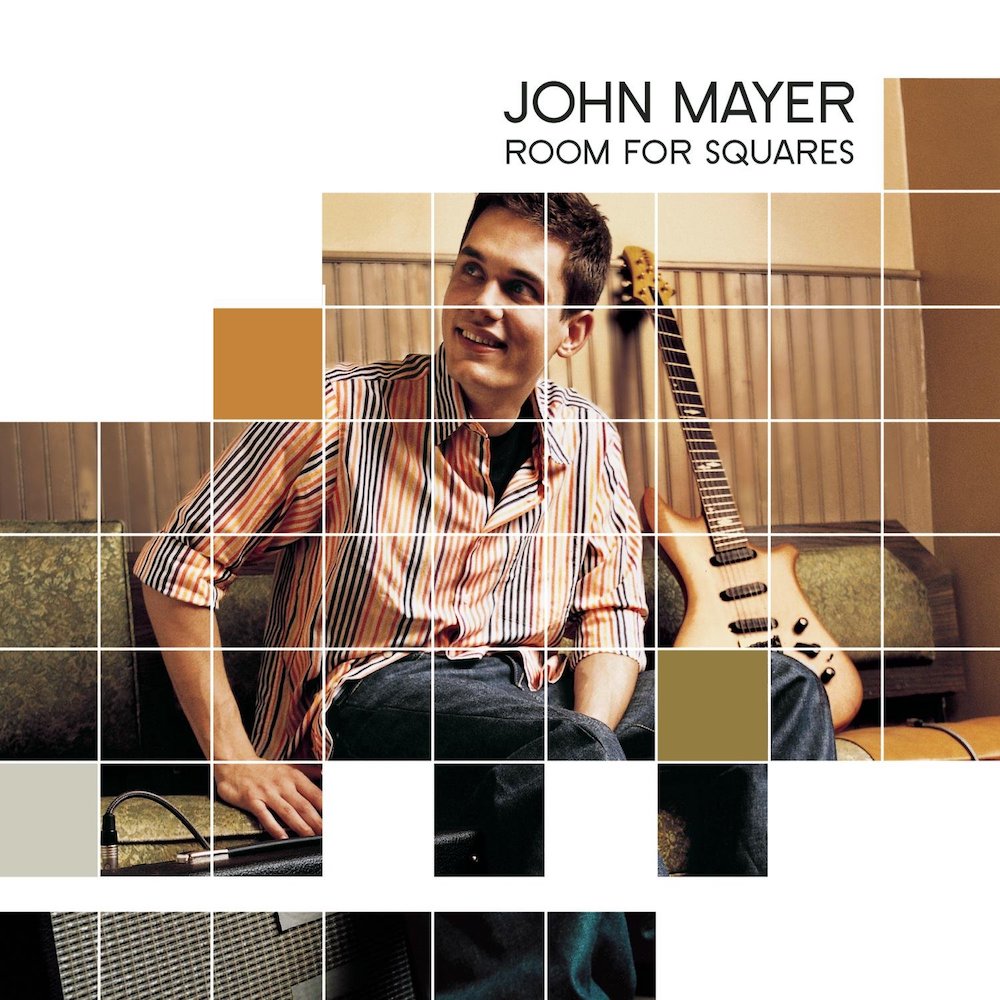

- Columbia

- 2001

John Mayer grew up wanting to be Stevie Ray Vaughan. But as the release of his major-label debut neared, he was more concerned with not becoming Shawn Mullins. An ex-Airborne Corpsman and native Georgian, Mullins was a big deal in Atlanta’s independent guitar-music scene. The year after Mayer dropped out of Berklee College and moved to Atlanta, Mullins parlayed his adult-alternative song "Lullaby" -- a tender, rasped-out portrait of a done-wrong Angelena -- into a good old-fashioned bidding war. Mullins chose Columbia, which took "Lullaby" to #7 on the Hot 100 and the top of the Triple-A chart. The follow-up single "Shimmer" got a replacement-level video treatment and crucial placement on the soundtrack for WB teen drama Dawson's Creek. It wasn’t that Mayer begrudged Mullins his shine. He just recognized what happens when you hit like a Texas flood. "My point of relativity... is Shawn’s success," he told Creative Loafing in 2003. "I also saw how it made a lot of people very frustrated and very competitive around him, and I wonder if that same thing happens with me. I feel a lot of this pressure, but the bottom line is, this is all par for the course."

By that point, Mayer’s course was pretty neatly laid out. Room For Squares (originally released by Aware Records 20 years ago on Saturday, then expanded and reissued the following September when Columbia exercised its signing rights on Mayer) was a phenomenon you rarely see anymore: a slow-burning smash. It took until March 2003 to reach its Billboard Top 200 peak of #8; its final single (the precipice-of-greatness tale "Why Georgia") was released in April, just a few months before the follow-up album dropped. On the whole, critics had found him refreshing: a young man making sturdy, unhurried guitar pop and good interview copy in equal measure. In a four-star review, Anthony DeCurtis of Rolling Stone attested to hearing bits of Elvis Costello and the Police. In Blender, Ann Powers picked up James Taylor vibes. Read all the reviews straight through, and you'll detect a tension between Mayer's sophisticated stylistic leanings and his obvious appeal to younger listeners. The 2002 double-disc live set Any Given Thursday cleverly heightened the contradiction: jazzier, eight-minute arrangements punctuated with appreciative screams. It also placed him within a number of pop lineages. There's a cover of "Message In A Bottle" that channels solo Sting's medium cool, a medley of "Girls Just Want To Have Fun" and "Let’s Hear It For The Boys" inserted into the kid-again lament "83." And, perhaps most meaningfully, he drops into a cover of Vaughan's instrumental ballad "Lenny."

After all, in the '90s, he was a rare bird: a guitar obsessive who yearned to be a pop star. This is a guy who spent countless hours practicing Vaughan's fretting and muscular rubato. A guy who used an Albert King quote for his senior yearbook -- a fact he relayed in 2013, when posthumously inducting King into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. In college -- famously, a time to expand one's sense of the possible -- he merely switched niches, earning spare cash by selling Ben Folds Five concert bootlegs. (Alerted to the breach, Folds spared the rod, earning himself a future opening slot on the Continuum tour.) Flailing at Berklee amongst more dedicated students and flashier players, he and a friend from school, Clay Cook, took their demo tape down to Cook's native Georgia. They billed themselves, tragically, as Lo-Fi Masters. In no time, they established themselves as an open-mic force.

But Cook was less interested in going the pop route, even as he, ironically, had come to see himself as something like John's song doctor, helping him streamline his compositions. Before the pair could begin overdubs on their debut record, they split up. Cook left for California and a gig in the Marshall Tucker Band. The Masters' would-be producer Glen Matullo (who had recorded "Lullaby" a couple years prior) fronted Mayer studio time and pressing costs for his debut mini-album, 1999's Inside Wants Out. The album is mostly just Mayer and his guitar, offering the exact tuneful, weightless introspection that clogged the counters in every college town at the time. There are lovely moments where you can picture him in the dark, singing his future into being. There are also times when he’s pining for an ex who "could distinguish Miles from Coltrane" and you look at your watch, waiting for him to turn 30.

When talking about debuts -- especially after the artist unveils a Patchy Second Album -- people love to say things like, "Well, with that first album, she was basically working on it her whole life." I don’t know if that quite captures it, especially for bands, which even in their happiest states are still subject to multiparty negotiations. But for solo acts, perhaps it's more accurate to say that the first album offers the longest runway toward whatever your sound's going to be. For Mayer, that sound was adult alternative: nagging guitar figures, unshowy mastery, introspection suitable for the mall PA.

Which is kind of funny, since he was barely an adult himself. When he dropped Room For Squares at the age of 23, reviewers tended to examine him in relation to the reigning Triple-A Davids, each about a decade older than him. There was the bleating David Gray, who sang everything like it was a golden hour. And there was Dave Matthews, to whom Mayer’s vocals were most often compared. (John was, for the record, going for the SRV thing, though he did play Dave's signature DM3MD Martin acoustic throughout this album.) Mayer's sound was fuller than Gray's, but far less propulsive than DMB's: "Love Song For No One" drives the hardest here, though it's still half-awake power pop.

And unlike Matthews -- who sought out the hottest local jazz musicians to torque his compositions into position -- Mayer's support on Squares was mostly ringers. Bassist Dave LaBruyere (a one-time member of bedeviled Americana group Vigilantes Of Love) had taken Cook's spot on those Decatur stages. But his partner in rhythm was Nir Z, an Israeli drummer who had played on Genesis' final, Phil-less LP. Keyboard duty fell to Brandon Bush: future member of Train, lifetime brother of Sugarland's Kristian Bush, contributor to Mullins' Columbia debut Soul's Core, and great-grandson of cannery titan Andrew Jackson Bush (no relation to Jackson Cannery). Overseeing it all was longtime DMB mixer/producer John Alagía, who had one goal: Put everyone’s focus on Mayer.

It worked. For all his six-string woodshedding, the instrument that immediately hits is Mayer's breathy baritone. Matthews will frequently augment his limited range with some cockeyed bark or audible smile. Here, Mayer offers no such warning or wonder. From first to last, this is a crooner's record, something Michael Bublé might make if he wanted to impress more than entertain. It is sexy, but determinedly so. Sometimes that's to the best: His measured half-whisper was the only way "Your Body Is A Wonderland" could be put over. ("This song is about foreplay," read the description on MP3.com. "This is a song about girly parts," he grins on Any Given Thursday.) He speaks of his lust ("I'll never let your head hit the bed/ Without my hand behind it") as a matter of fact, and in doing so -- as Marc Hogan noted in his review a couple years back -- enters the earnest, unbothered lineage of R&B. The friends-with-benefits portrait "City Love" (with a woozy John Mark Painter string arrangement, recalling his work for, yes them again, Ben Folds Five) is necessarily more detached, but Mayer offers it like a deadpan vignette. They mumble goodnight from separate beds, each of them transmitting their neighborhood sirens over the phone. She pops over to his place in the pouring rain; he thinks it’s romantic, but realizes she’s using his dryer for free. When he says "I love you" he knows it's over.

But the narrative heart -- both for Squares and Mayer himself -- is established within the first two tracks. "No Such Thing" has the smug certainty that's so crucial in youth. Having figured out the sham of suburban striving, Mayer fantasizes about returning to his high school to warn everyone. "I am invincible," he intones on the bridge, "as long as I’m alive," and a synth hook drifts into the clouds. It's one of the best Triple-A singles of the decade. Levitating off a keening falsetto and one of his stickier acoustic figures, "Why Georgia" is the postgrad check-in, a bleary-eyed look at total freedom without the validating success. (It also popularized the phrase "quarter-life crisis," first brought to mainstream attention by a stat-free, interview-reliant pop-psych book.) "I wonder sometimes," he muses on the pre-chorus, "About the outcome/ Of a still-verdictless life."

Those two notes -- confidence and deprecation -- formed the interval Mayer would hammer in interviews for years to come. He'd condemn the desire to become the hottest guitar player, leaving room for you to infer that he still thought he was pretty damn good. He was persistently open about making music for the masses -- a noble endeavor that, he had to stress, wasn't too taxing. "For the most part, I'll write a song in one night and go, 'How could I not?' It's just in me," he told MTV News in 2002. "It's not a cocky thing, 'cause I feel pretty objective in the sense of what I don't nail and what I do." Or, as he confessed in 2003, when accepting a Grammy for "Your Body Is A Wonderland," "I'm always thinking about being palatable to the people at home."

In the moment, it came off as sardonic. But Mayer digs fame, and has always been willing to play the game. In the mid-2000s, that meant leaning into hip-hop’s appreciation for his slick chops: doing backing vocals on a Kanye-produced Common single, playing off Questlove in a Dave Chappelle sketch, letting Nelly out-rock him with a "No Such Thing" interpolation. In time, with his star fixed, it would also mean playing the raconteur in magazine pages, which, apparently, meant free-associative racism and heinous oversharing about his personal life.

But those were choices he had yet to make. Recording Room For Squares, he was a rookie quarterback with all the tools the pros craved: talent, work ethic, sharp mind, physical makeup. And the most crucial one: ambition. The month after the album dropped, Billboard’s Melinda Newman observed him scanning a full house at LA's storied club Troubadour. "Who knew?" someone beside him asked. "I know," John answered. "I'm the mayor of Who-Knew-Ville." It is difficult to imagine Shawn Mullins saying anything like that.

Once the Soul's Core promotional cycle ceased, Mullins and Columbia began clashing. They broke him on radio, so they wanted more radio hits. Mullins knew he would do best cultivating a diehard fanbase, and wanted to release something designed for that. Speaking to Bowling Green's The Amplifier in 2012, Mullins reminisced about his odd-fitting pop-culture moment, which led him to consider the lanky kid who, for a while, navigated him like the North Star. "Of course, his success eclipsed mine by far," Mullins said. "But he always really wanted more than I wanted."