- Saddle Creek

- 2002

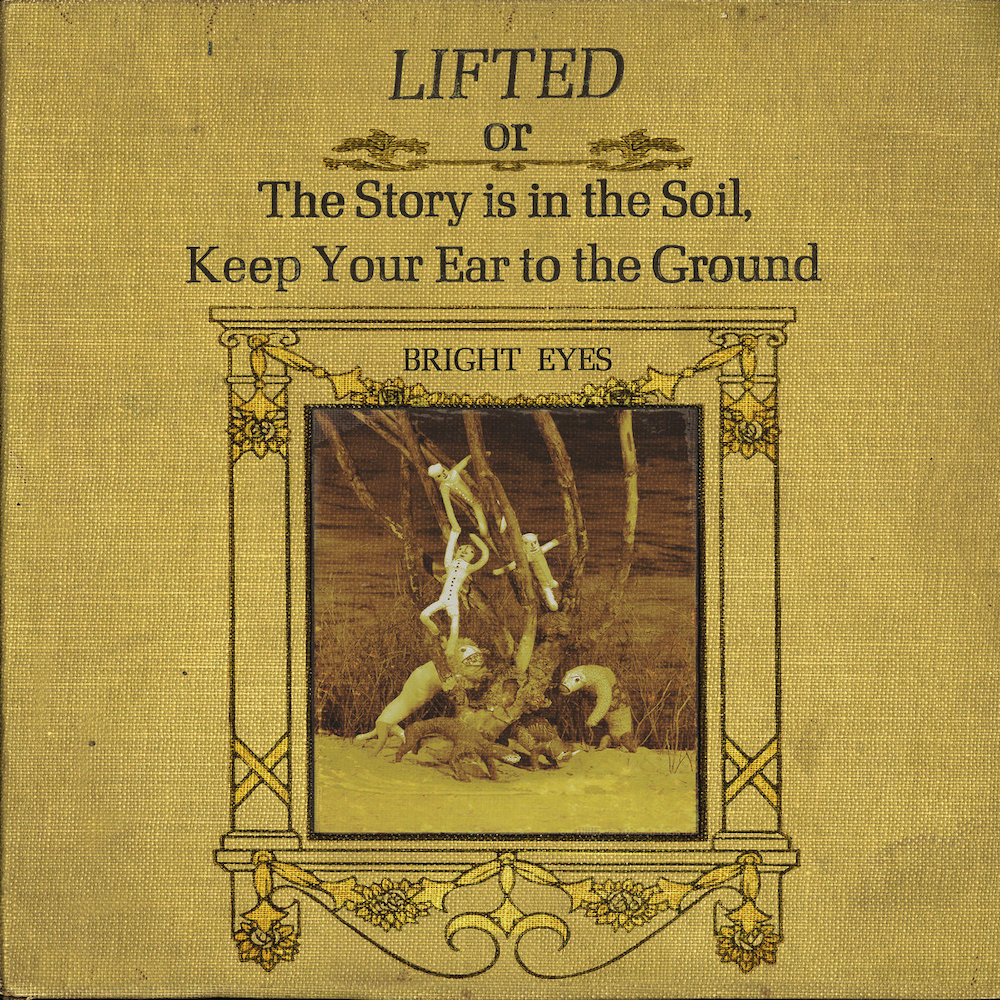

There's an extended scene in Freedom, the 2010 novel that landed Jonathan Franzen on the cover of Time, in which an aging indie rocker finds himself at a show in Washington, DC. He's there to see "the suddenly hot band Bright Eyes, fronted by a gifted youngster named Conor Oberst." The scene takes place in the early '00s, and all around him, the character Richard Katz sees evidence of a younger generation that's lost touch with rage. The "kiddies" at this show -- "the flat-haired boys and fashionably unskinny babes" -- have "gathered not in anger but in celebration of their having found, as a generation, a gentler and more respectful way of being. A way, not incidentally, more in harmony with consuming." Here's how Franzen -- or, fine, Franzen's character -- describes young Mr. Oberst:

Oberst took the stage alone, wearing a powder-blue tuxedo, strapped on an acoustic, and crooned a couple of lengthy solo numbers. He was the real deal, a boy genius, and thus all the more insufferable to Katz. His Tortured Soulful Artist shtick, his self-indulgence in pushing his songs past their natural limits of endurance, his artful crimes against pop convention: he was performing sincerity, and when the performance threatened to give sincerity the lie, he performed his sincere anguish over the difficulty of sincerity.

Funny thing: If I've got my timeline right, the fictional Richard Katz would've gone to see the real Conor Oberst when Bright Eyes were touring behind Lifted Or The Story Is In The Soil, Keep Your Ear To The Ground, an album that will turn 20 tomorrow. That means I was at that show -- or at the real version of that fictional show, anyway. It was at the smaller Black Cat, not at the 9:30 Club, and the room wasn't even full. (Franzen later claimed he'd never even set foot in the 9:30 Club.) Conor Oberst did not take the stage in a powder-blue tuxedo, and he did not play any lengthy solo numbers. Instead, at least in my memory, Oberst had a backing band that consisted entirely of cute girls. And he was mad -- not at the perilous state of the world around him, but at the audience that wouldn't stop talking through the show. It was a weird vibe.

Lifted was the true beginning of Conor Oberst's whole boy-genius trajectory. Oberst had been a literal child when he started making Bright Eyes records. He was 22 when he released Lifted, and it was his fourth album. Collegiate emo kids like me had fallen all over Fevers And Mirrors, the album that Bright Eyes had released a couple of years earlier. (I already used the anecdote about that Black Cat show in my 20th-anniversary piece about Fevers And Mirrors. Forgive me. I have a finite number of anecdotes.) But on the ground, out in the world, all those kiddies didn't yet see Conor Oberst the way that the Franzen had depicted him. They would, though. It was coming. Oberst would get himself fitted for a powder-blue tux soon enough. A year later, rumors would circulate that Oberst had been dating Winona Ryder, thus living out the dreams of every straight male indie dork in his generational cohort. Lifted was the record that got him there.

As for Jonathan Franzen's point about Conor Oberst's performative sincerity, his "Tortured Soulful Artist shtick": fair enough. Lifted is the work of a young man who's determined to be taken seriously. It's long and pretentious and gimmicky and tremulous. It's full of lush acoustic arrangements. At the time, I heard the album's sound as Oberst's attempt to live up to the young-Dylan archetype and to distance himself from the emo scene that had embraced Fevers And Mirrors, and I'm still not convinced that I'm wrong. (It was a genuine shock to see Bright Eyes on the bill for this year's emo nostalgia-fest When We Were Young. Oberst always seemed to hate it when people would file Bright Eyes next to Braid in their CD collections.) But Lifted is also pretty great -- sometimes despite all those excesses, sometimes because of them.

Those excesses are real. At 73 minutes, Lifted strains the storage capacity of a compact disc, and it doesn't even include all the songs that Oberst was cranking out at the time. There's a new companion-piece EP coming with a Dead Oceans reissue later this year. When Bright Eyes played Letterman to promote Lifted -- the band's first-ever TV appearance -- they played "The Trees Get Wheeled Away," a song that wasn't even on the long-ass album. At various points, the ambitions of Lifted practically render the album unlistenable. Some songs sound like they were recorded on boom boxes in dumpsters. Some cut off mid-syllable. Oberst includes multiple false starts and skits, to the point where I remember the aborted "on a string..." bits from "False Advertising" as much as the song itself.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=R6qLkaMa-Xc&ab_channel=bradleyjerome

Lifted opens with a solid minute of muffled dialogue, a recording of Jenny Lewis and Blake Sennett, then bandmates in Bright Eyes' Saddle Creek labelmates Rilo Kiley, seemingly murmuring at each other while driving through Omaha snow. That's a slightly unbearable touch, but it's also a quick indication of the sense of community that drives the album. Back when Rilo Kiley were on Saddle Creek, they were Californian outliers. The label, founded by Bright Eyes producer Mike Mogis and Conor's brother Justin Oberst, was mostly built around a tight-knit crew of Omaha musicians, and those musicians are all over Lifted. Members of Saddle Creek bands like Cursive, the Faint, Now It's Overhead, and Azure Ray play and sing on the album, and they all add to the sense of sweep. It's a roots-rock orchestra comprised entirely of local buddies, all there to see this kid's vision to completion. When all the tape hiss and the self-serious experimental flourishes fade away, it's beautiful.

The beauty is the point. In a lot of ways, Lifted is an album about self-loathing. Some of that self-loathing belongs to Oberst himself: "I know what must change/ Fuck my face, fuck my name/ They are brief and false advertisements for a soul I don't have." Some of it belongs to the other people in his life. "Waste Of Paint," the song that hit me hardest back in 2002, is Oberst seeing that same self-loathing in all the people around him, whether or not they had artistic brilliance to share. (The whole vignette about the cop now plays out as sheer fantasy, but that song still hits hard.)

All through Lifted, Oberst holds up the act of making art as the way to overcome all that self-hatred, or at least to capture that self-hatred for posterity: "Michael, please keep the tape rolling/ Boys keep strumming those guitars/ We need a record of our failures/ Yes, we must document our love." Oberst sings about being "lifted" on sound, about transcending through creation. Sometimes, he seems unsure whether that can redeem anything. A couple of songs are about Oberst's selfish shittiness in romantic situations. "Lover I Don't Have To Love," the album's closest thing to a hit, is all about bad actors with bad habits and sad singers who just play tragic, and no singer is sadder than Oberst himself. He knows he's full of shit. But sometimes, when the light shines right, he feels like he can do something good.

That struggle between earthly degradation and artistic uplift is the engine of Lifted, the driving force. I think that's why Oberst left all the flaws and fuckups and pretentious moments in there -- yelling out "mistake" just before making a mistake, that kind of thing. I don't think Conor Oberst trusted himself to make something beautiful without struggle, and he wanted the struggle to come through in the finished product. Those ideas don't all work, but there's something cool about making audiences work harder to reach the moments of glory. And there are so many moments of glory on Lifted, musical swells and anguished howls and goosebump-raising turns of lyrical phrase. Conor Oberst might not have trusted his own voice, but the kid knew what he was doing.

Conor Oberst is almost exactly my age. He was 22 when he released Lifted, and I was 22 when I bought it. If he'd been any older, he could've never made that album. If I'd been any older, I would've never had the patience to embrace it. (If Lifted came out in the streaming era, I'm not even sure I would've made it through "The Big Picture.") Listening back to Lifted now, I sometimes find myself getting impatient -- with the overstated imperfections and with the self-obsession on display. Two decades later, it's more clear that you can't overcome your own shittiness by singing about that shittiness, and Oberst's romantic tales of woe don't have the same romance. But the album still works. It still hits some chord. When Oberst is braying about his absent God, his need to believe and to be loved in his soul, I still feel something. Oberst was channeling big feelings on Lifted, and some big feelings don't age.

Jonathan Franzen might've written about Conor Oberst as some generational figure, but that's not what I saw at the Black Cat that night. I saw a guy struggling to assume the public mantle that he thought he wanted. Oberst got that public mantle. Lifted became the first Bright Eyes album to land on the Billboard album chart, back when that was still a real achievement. Soon enough, Oberst made another grand statement, and it was the type of grand statement that invites the world in rather than artfully seeking to repel anybody. That statement, however briefly, made Conor Oberst a star.

Even after that statement, though, Oberst never quite became a generational figure. He kept singing about himself as a mess, and he kept being a mess. Today, Oberst and I are both about the same age as that Jonathan Franzen character who was so appalled at what he saw at the fictional 9:30 Club that fictional night. But Oberst still looks about the same, and he still makes a spectacle of his own messiness. A few months ago, for instance, Oberst was playing in Houston, and he cut off his own show by doing what he advised that crowd in DC to do 20 years ago: He left. Oberst stormed offstage mid-song early in the set, leaving his bandmates to attempt to lead a Bright Eyes karaoke night, with fans standing in for him. But when I saw Bright Eyes last year, that messy intensity made for an electric night. Conor Oberst was still putting his flaws on display, and he was still making those flaws compelling. Jonathan Franzen could never.