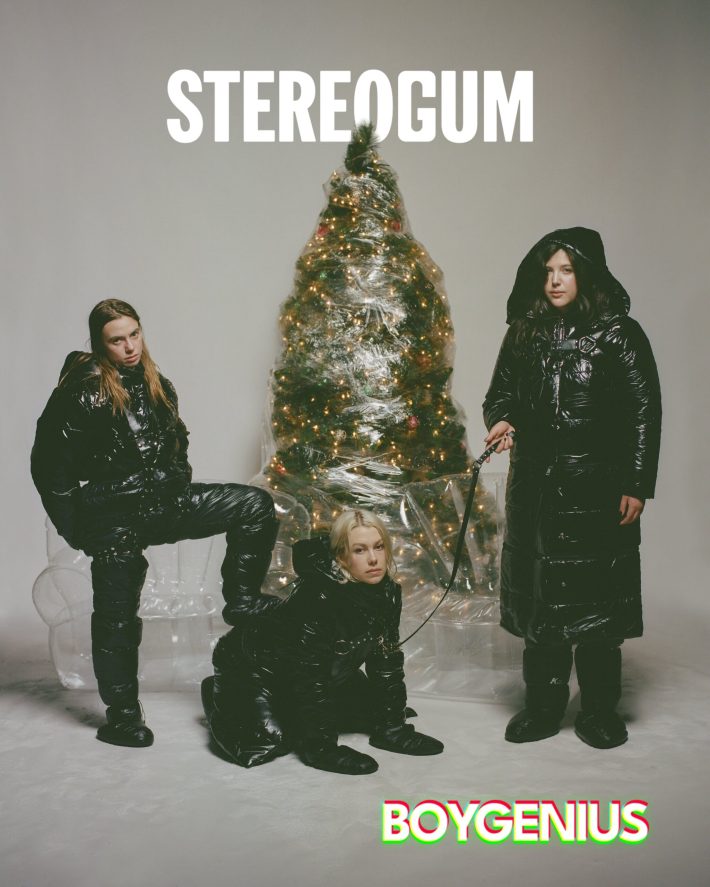

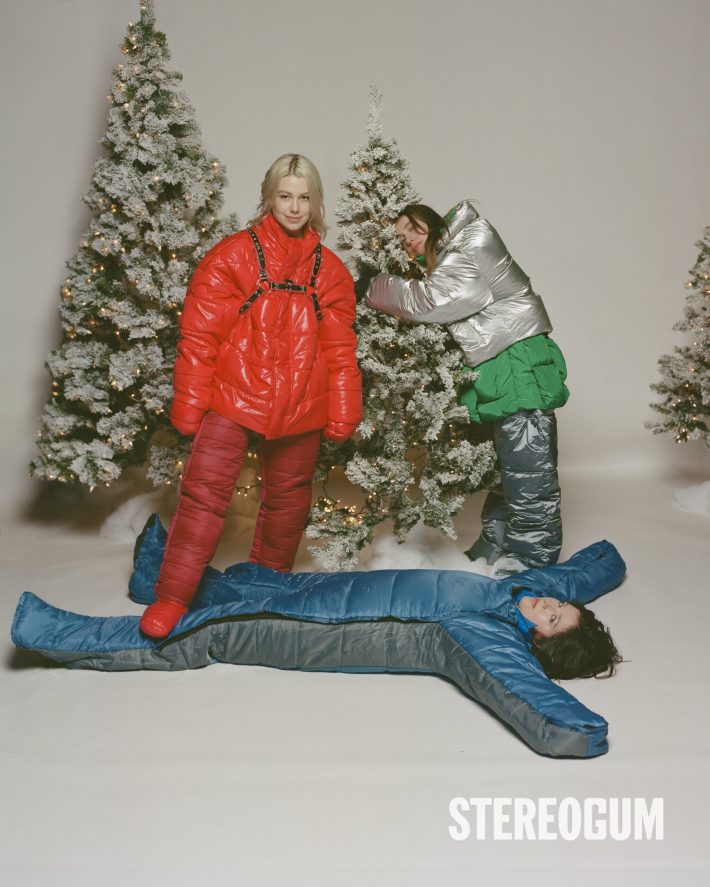

Artists Of The Year Julien Baker, Phoebe Bridgers, and Lucy Dacus look back on their joyful and triumphant 2023

Justin Bieber is about to cry.

It's Halloween evening at the Hollywood Bowl. "Justin Bieber" is the best description I can give to the tall gentleman standing to my left, sporting a vague amount of tattoos and wearing a too-long white tee and electric pink beanie. About half of the 18,000 attendees at this sold-out show are dressed in costume. The Grease Pink Ladies huddle to my right. A Doc Martens-wearing Jimmy Neutron, Dairy Queen cone-shaped wig and all, sits in front of me with hair somewhat blocking my view. Behind me, Joe Dirt and two shaggy Jesuses sway in time.

Earlier, in the longest merch line I've ever seen at the Bowl, I spotted angels, devils, Waldos, a few Barbies (no Oppenheimers), some The Bear chefs, and at least 67 skeleton outfits inspired by Phoebe Bridgers' Punisher. Now, from my perch in the audience, I can see massive inflatable devil horns, lit up in blood red, on each side of the amphitheater's iconic bandshell; even the Bowl dressed up for the occasion. "Justin Bieber," I can't tell. Maybe his costume is "vibe." He had been bopping through the opening band, 100 gecs, with that unbothered Southern California glee. In LA, even on Halloween, it's hard to tell who's in costume and who's just manifesting. He probably got an Erewhon smoothie before the show. I'm glad he's having a good time, I think.

"Justin Bieber" is now dead silent. So are the other 17,999 people here. The song emanating from the stage is "We're In Love" by the evening's headlining band, boygenius, the supergroup that matches the aforementioned Phoebe Bridgers with her fellow singer-songwriters Julien Baker and Lucy Dacus. The performers are also in costume, forgoing their usual suits and ties. Bridgers is the Holy Spirit in the vein of Tim Burton's Corpse Bride, wearing a sheer gown with a silver cross visible across her chest and a crown of pearls. Dacus is the Father, wearing a heavenly halo and a white disco jacket worthy of Gram Parsons. In-between Bridgers and Dacus is Baker as the adored Son, Christ, with a crown of thorns, a white robe with a large crimson sash, and painted-on tears. The touring band members dress as angels with wings.

"We're In Love," led by Dacus on vocals, comes in the middle of boygenius' Bowl debut — the last show of a long tour that has kept boygenius on the road on and off for months. I had anticipated this silence. Though never released as a single, "We're In Love," like many boygenius songs, takes on new life and importance on stage. The song features only faint acoustic guitar strums accompanied by light piano and then gentle strings, weeping like some bittersweet memory. The point is not the instrumentation, highly competent and pleasant as any boygenius song. The point is to listen to Dacus. That's who the crowd is quiet for. A silent Bridgers and Baker know this too.

A few weeks ago, a similar experience happened when the boys (as they're called by their supporters and sometimes by themselves) made their Madison Square Garden debut in New York. If that MSG concert was, in the words of Pitchfork's positive review, the world's largest bisexual convention — with "Oh my god, we made it" energy from the band and audience also in disbelief — this Bowl debut feels more like a relaxing retreat playing to an already accepted truth: This is a widely beloved and successful band performing to its adoring fans. I was curious how their arena show would translate to the outdoors. I did not expect the silence to suck up all the noise and oxygen from the amphitheater air. I didn't think any band could do that. Bridgers and Baker eventually join their bandmate in quiet harmony. They help Dacus carry the song home. So does the rest of the Bowl.

It's an outstanding performance. I'm moved to see Dacus' masterful control of her voice and the song's melody, the near silence the performance commanded, and the front-row audience handing her pink carnations in honor of the song's lyrics ("I'll be the boy with the pink carnation pinned to my lapel/ Who looks like hell and asks for help"). The band has just performed "Leonard Cohen," a quasi-interlude also sung by Dacus that name-drops the titular songwriter as a self-aware wink: Yes, we all still love a horny Silent Gen poet. At this moment, "We're In Love" could be a Leonard Cohen song — one synth pad away from "In My Secret Life" transcendence that I already feel will influence the next generation of singer-songwriters. The crowd loves this. It feels like the crowd needs this. The band too, in a way. For some reason, I also have a nagging feeling: This feels like the end of something.

This has been the year of boygenius. In January, Rolling Stone announced the group's return with their official debut LP the record, their first release since the 2018 self-titled EP that made them one of indie rock's most fiercely beloved bands on the strength of just six songs. The article was paired with an instantly famous magazine cover — famous because boygenius recreated Nirvana's own iconic 1994 Rolling Stone cover. When I first saw the photo, I laughed in admiration at the trio's boldness to put themselves in direct conversation with the boy geniuses who, for a long time, have dictated the evolving stories and self-sustaining myths of rock 'n' roll. (I am legally obligated to mention that boygenius did something similar with their debut EP artwork, which mirrored Crosby, Stills & Nash's self-titled album.) I also remembered that Nirvana's story ended in tragedy. The stern yet confident look from Baker, Bridgers, and Dacus on the cover seemed to suggest a dare: Watch us succeed.

Succeed they did. Boygenius are Stereogum's inaugural Artists Of The Year. Outside of Taylor Swift, no act's presence was more consistently felt throughout 2023 by this publication's readership. The record went #1 in multiple countries, a first for each member, and peaked in the top five in the US. The album's first three singles were paired with a 15-minute music video directed by Kristen Stewart. Pretty much every major publication published a glowing profile (2023 was a breakout year for the word "sapphic" in music journalism). Swift may be more well known around the world, but the world's foremost music journalist Nardwuar did not gift Swift her own custom triple-boost guitar pedal.

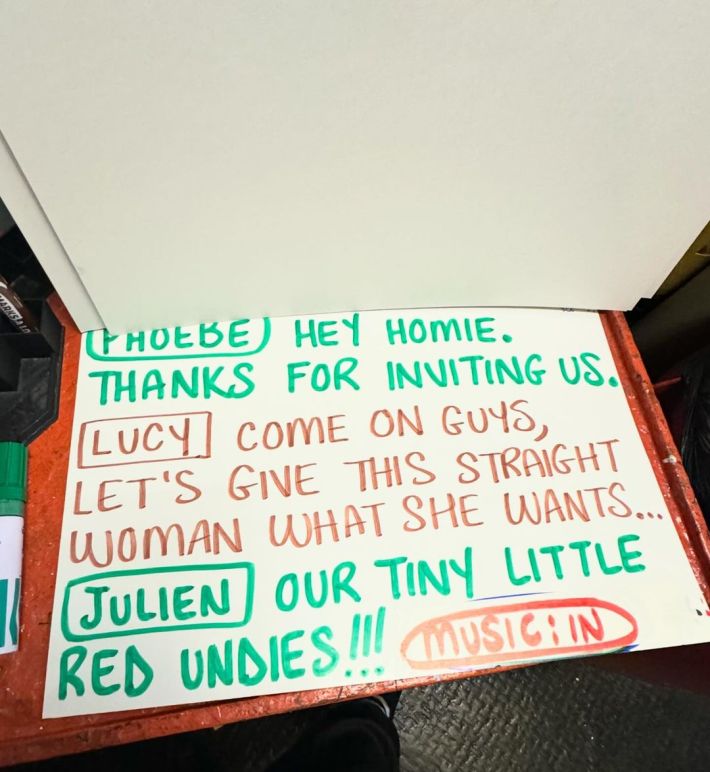

In the spring, boygenius seemed to perform everywhere, from Coachella to Philip Glass' Tibet House benefit, from CBS Saturday Morning to the airport baggage claim during SXSW. After touring all summer on both sides of the Atlantic, their profile rose even higher in the fall. In a nice little full-circle touch that seemed to put a bow on the year in boygenius, Nirvana's own Dave Grohl played drums for the boys at the Bowl. Then, in the span of 48 hours one November weekend, boygenius earned six Grammy nominations (including Album Of The Year and Record Of The Year) and were musical guests on Saturday Night Live, where they'd been name-checked by Bowen Yang in a joke weeks earlier. On SNL, not only did they perform the customary two songs in a setup nodding to the Beatles on Ed Sullivan, they appeared in a sketch as night demon Troye Sivan clones alongside host Timothée Chalamet. It somehow entirely made sense.

This was the perfect storm. Before 2023, Baker, Bridgers, and Dacus already had successful solo careers with built-in audiences and refined interview and social media brands. Though they'd risen to prominence working in an indie ecosystem — Dead Oceans for Bridgers and Matador for Baker and Dacus, two of indie rock's more robust labels — boygenius released the record through the Universal-owned Interscope, making it the first major label release for all three. Whatever heights they'd climbed before, the record made them legitimately famous, or at least famous enough that when Bridgers brought out Baker and Dacus during her Nashville opening set at Swift's Eras Tour, the knowing crowd freaked out. (Swift herself praised the record on Instagram). Maybe this album cycle was just the excuse to crown these three artists with the fame that their fans and industry insiders already believed them to possess. Either way, boygenius officially joined the big leagues.

I'm driving toward Studio City in the Valley to meet the boys. The weather is cool — nowhere near the 103-degree conditions Bridgers sings about in "Voyager," a highlight from the band's recent the rest EP. Compared to the earthy and sunkissed the record, the rest slightly expanded the boygenius sound to add more spacey and overt electronic flourishes. Both are sunset listens. Both still attract the same level of scrutiny from fans determining who originally wrote what songs and what lyrics are about whom, in or out of the band. The EP was also strategic, releasing around the first-round voting window for the 2024 Grammys as if to remind the Recording Academy of boygenius' dominance over the year.

In recent weeks, I've used LA's famously gridlocked traffic to listen to the record and the rest and brush up on each member's solo discography. Today's trip is long enough to fit in the entirety of the record. The day is pristine, with blue skies and Toy Story clouds. I wish the weather was darker; the record has a yearning melancholy that sounds best in the autumn. I cross the Hollywood Hills on my way to meet boygenius on a Ventura stretch known informally as Sushi Row. The Valley unfolds ahead of me in light smog haze. Caught up in light afternoon traffic, I imagine all the business lunches happening in these unremarkable-looking strip malls that are determining the fate of America's film and entertainment industry.

I'm the first to arrive at our restaurant hidden among the strip. Baker and Dacus soon arrive together. Bridgers is late due to traffic. A round of pleasantries turns into a game of not trying to feel overwhelmed by the multiple massive lunch menus. The mood is relaxed. The excitable meta-cockiness from the spring press cycle, perceived or not, has given way to the calm and reflective spirit of fall. Or maybe the band said everything it wanted to say during the spring and can now just enjoy a meal.

Dacus, in an all-black jumpsuit, is the most careful with her words, taking her time to make the most direct points in a calm tone not unlike her singing voice. Baker, in a black shirt, is the one most willing to dive in and explore various conversational rabbit holes; a question about her 2023 highlights soon evolves into a breakdown of Franz Kafka's The Trial and how governmental power comes from letting the masses dissent in fashionable ways to give the illusion of autonomy. "I agree," Dacus says after a beat, smiling. She's a pro at following Baker through the weeds. Throughout our interview, I can sense Dacus picking and choosing when to let Baker go into one of her deep dives and when to reel in the conversation. Sometimes, Dacus dives down the rabbit hole too. We still need to decide what to order.

"I think this is the first place I ever had eel," says Dacus, sharing that she came to this same restaurant with her first manager when she signed a publishing deal. "I was like, 'This is the coolest thing I've ever done.’"

"The first place I ever had eel was my college university food court," adds a deadpan Baker. "Maybe that's why I don't like eel."

We settle on miso soups, toro and vegetable rolls, and spicy tuna tartare.

"Phoebe will fuck that up," Baker says of the tartare.

The restaurant is not crowded, save for a nearby party giving the occasional glance, who may or may not recognize Baker or Dacus. As we wait for Bridgers, we do some further ice-breaking on a variety of topics. Barbenheimer (all three dressed up and went together, but none liked either movie). Chicago winters (Dacus' mom is from the greater Chicagoland area). Food trucks (the only way to save money in LA). Trader Joe's frozen chicken nuggets (the best). Shopping at the Grove (Dacus: "I cannot be coming back here willy-nilly"). The logistics of how to stay healthy on tour (at Bridgers' suggestion, boygenius hired a tour chief; Dacus and Baker confirmed it was a game changer). Bob Seger (we all approve). When Bridgers finally arrives with a chipper "Hello" dressed in jean overalls and a Viagra Boys hunting hat, Baker, Dacus, and I are discussing Hoagy Carmichael.

"Sounds like a made-up name," Bridgers says. "Who's Hoagy Carmichael?"

"He's an old songwriter," Dacus says. "I love him."

"Did Hoagy do a version of 'A Dreamer's Holiday'?" Baker asks. "I covered that. They used to put many a chord into a song. So many chords in learning old '40s songs."

"We are looking at the death of chords," Bridgers says.

"Mmmmm-hmmmm!" grunts Baker, trying to disagree while finishing a bite of sushi.

"I have a lot of chords in my songs," counters Dacus.

"I mean in popular songs," Bridgers replies.

"Oh, right," Dacus says. "Yeah, three to four. But chords aren't what make the song good or bad. I would encourage good songs. I don't know. Sometimes, when a trend emerges, the opposite starts to feel good."

This is the typical boygenius flow. We immediately feel Bridgers' presence now that all three band members are here. She often speaks as the industry veteran of the group. Until this year, Bridgers was the only member who had played SNL and been nominated for Grammys. She was the most vocal of the trio in her conviction that even before making the record, boygenius would one day play Madison Square Garden. She frequently steers the conversation in different directions, with Baker and Dacus politely listening and mostly waiting to respond. She catches herself doing this.

"You haven't asked a single question," she laughs a good while into our interview. "I just showed up and started talking." From the chord talk, we segue into their general thoughts on songwriting and production at their new level of popularity, which turns into a discussion about what a modern producer even does. To Bridgers, it can mean a glorified engineer who takes 15% of each song they work on. ("I'm talking about a specific person, but I will not name them.") Or it's a dude who says, "You know what would be cool? Reverb."

"I feel like that's my only production note ever," Baker says. "Reverb."

Dacus counters that the role of a producer is to establish the structure of making a record, citing the trio's work with Catherine Marks, the producer of the record who, per Bridgers, is essentially the fourth member of boygenius. "The one [producer] I don't have a problem talking shit about is Ryan Adams," Bridgers says. "When I recorded with Ryan, I played a song just one time, and he goes, 'That's perfect.' I'm like, 'I bet by the third pass, we could decide which one.’" Dacus' tip for that situation: Keep doing takes until one is worse.

I ask about 2023 band highlights. Dacus right away brings up Belgium's Pukkelpop Festival on a day that was so hot that she and Bridgers ripped their shirts open, something they would do again at MSG. "Something I would have been really afraid to do on my own just felt totally fine [in the context of boygenius]," Dacus explains. "After we got offstage, I didn't put my shirt on. I definitely had some anger of, 'Why can't I just do this?’" "Especially because Europeans are like, 'Cool,’" Bridgers adds. "And then everyone online in the US was like—" at which point Baker chimes in, gasping loudly in a dramatic clutching my pearls voice. ("I just thought it was weird," was Dacus’ mom's response, the musician shared on Instagram after MSG. "You make your choices.") Bridgers looks back fondly on the record's release day and their European tour. For Baker, it was seeing kids at early boygenius shows already knowing all the lyrics. "It felt good for the entity of the band to be loved and for people to also have investment in whatever it symbolized to them of us continuing to make music corporately," Baker says. She's excited for the next couple of years, for a new era of trusting and believing her own words. "I was just waking up to a lot of incremental changes. I hadn't noticed what was happening until I'd been surrounded by y'all for two years. The way I talk about myself is different. The way I defend my own ideas is different."

If they had to vote who should be Stereogum's artists of 2023, Dacus would pick billy woods. ("One of the best wordsmiths around right now — I hate that I said the word ‘wordsmith,’ but whatever.") Baker picks Mitski. ("That fucking record is a work of inspired genius.") Bridgers picks Palehound. ("Palehound. That's it.") I ask Dacus how she feels that she made it onto Rolling Stone’s updated list of the greatest guitarists of all time, ahead of Japanese noise rocker Keiji Haino and behind "Feliz Navidad" belter José Feliciano.

"That's so embarrassing," says Dacus, sounding caught off guard. "Julien should be on the list. I'm ahead of Kurt Vile! Have you seen me play guitar? Like, no. I have a style, but that doesn't mean I'm good." Baker and Bridgers immediately come to her defense, with Baker appreciating that good guitar playing isn't always about technical proficiency ("I'm not Steve fucking Vai") and Bridgers pointing out that the list is just to make people mad. If Dacus had to pick, her guitar intro to "Night Shift" is her signature guitar moment. "[That's] how I play guitar. I don't even know what chords I'm playing a lot of the time. I write lyrics and melody at the same time, and then I just have to find the chords afterward. Never took a guitar lesson. Never will."

I bring up MSG and whether the pressure to write bigger-sounding music to fill arenas informed the record. "It just didn't keep me up at night," Bridgers says. "When we started to hear what kinds of songs we were writing, Julien's songs were so rocking and heavy. And when we wrote 'Not Strong Enough' and it was a really fun one to sing along to, it was the most I ever felt like this music could be scalable of anything I had made before."

"I felt so proud of it," Baker states. "But when I make music with my friends, I am delusional."

"My delusions have only been right," add Bridgers. The trio laughs in agreement.

The album that best encapsulates any given year is not always the highest quality album of that same year, yet critics and fans were quick to declare the record a classic that checked both boxes. Baker, Bridgers, and Dacus had never released a bad-sounding record, but the record felt like the perfect alchemy of three singer-songwriters reaching their peak through a distinct artistic statement. In its best moments, like on "Not Strong Enough," which seemed scientifically designed in some offshore undisclosed lab to take over KCRW, the record comes off like a less bitter Bridge Over Troubled Water for the Lorem generation. Even the few lukewarm reviews — critiques included that it was a frontloaded album and had an aggressive mid-temponess that would make Jeff Tweedy blush — acknowledged how special this moment felt.

The idea that the record is frontloaded would not compute for boygenius, who've spent months on tour watching the tracks from Side B evolve into the album's emotional core. Bridgers identifies "We're In Love" as the private hit amongst the band. For a long time, it was also hard for her to sing the closer, "Letter To An Old Poet," the one song for which she asked the audience to put away their phones. "Satanist" has emerged as a live favorite. "It's the most fun I've had on stage," says Baker about what she affectionately calls that song's bonehead riff. "There aren't a lot of tracks on that song. It's just a band riffing." "There's an alternate reality where we didn't put out three songs first, and 'Satanist' was our lead single," says Bridgers. "I live in that reality sometimes." Dacus concurs, commenting on how the song feels heavy without feeling maximal, comparable to how the Pixies sound big with so little equipment.

That three assertive songwriters could come together and make something cohesive was not a given. The more I relistened to Baker, Bridgers, and Dacus individually and playing with one another, the easier it became to pick up on each person's distinct style. Baker is the riffer, the kind of gut-check guitarist who performs her songs as she discovers and writes them in real time. The post-punk riff that leads "$20" would fit right in on Little Oblivions. Bridgers is the director who performs in widescreen with her more cinematic arrangements and prime-time melodies. Any screaming on the record recalls the climax of "I Know The End" from Punisher, the album that gave Bridgers her own mainstream breakthrough a few years ago. (This year's Apple TV+ series Shrinking features Jason Segel dramatically sobbing to "I Know The End" while riding his bike — "Fuck you Phoebe Bridgers!" he cries before crashing into a car.) Dacus is the poet, the lyricist who can turn a song about wanting to kill your friend's dad into a John Hughes prom slow dance moment.

The three songwriters are similar in so many ways, yet their artistic goals are unique enough to fill in each other's gaps. If Baker, Bridgers, and Dacus were already on a shortlist of the most beloved indie artists of the second half of the 2010s (Baker was the first to release a proper debut LP with Sprained Ankle in 2015), the record feels like a collective victory lap of each boy's specialty that helped define this era of indie rock.

It's also possible to see the record as a closing chapter. A more nebulous reason for how boygenius defined 2023 is that how you talk about this band is, in a way, how you talk about the current state of Big Indie, the constellation of the genre's biggest and most accessible acts. Once a descriptor of DIY artists working outside the major label system, "indie" long ago evolved into a sound or aesthetic, an especially handy term for when tech platforms like YouTube, MySpace, and Spotify began to rely more on metadata to organize and promote public-facing content. What easier way to sum up Bon Iver, Japanese Breakfast, and the War On Drugs — all different-sounding artists who began independent but worked for years until they finally broke through to the mainstream — than to just tag them all as "indie"? Each era of Big Indie has its sound and aesthetic — The O.C. soundtrack, chillwave, now prestige pop — yet it's consistently been a possible pipeline to stardom embracing the technology and means of its time. It's a complicated history.

"I hadn't noticed what was happening until I'd been surrounded by y'all for two years. The way I talk about myself is different."

Julien Baker

Frazer Harrison/Getty Images

Boygenius are now a touchstone of that history. They have conquered (arguably transcended) the pipeline, and the record feels like the climax of Big Indie's current era. It makes sense. Here were three of the artists who'd helped to define the genre's ethos over the past decade — steering it toward earnest, lyric-focused singer-songwriter fare and away from cishet males as its center of gravity — now coming together to become something greater than the sum of its parts. Yet the gushing praise for boygenius this year seemed to go beyond their music. It was also rooted in an appreciation for a new kind of mainstream rock band: one in which the performers go out of their way to show how much they respect and support each other. In his interview with boygenius, Apple's Zane Lowe compared them to the Beastie Boys because they were each other's biggest fans.

But even a band so self-aware and so clearly in control of its narrative could be unwittingly dragged into other people's conflicts — the price of getting big. Some turned boygenius into social currency; in Rolling Stone’s official statement following co-founder Jann Wenner's controversial statements regarding Black and female artists, the publication listed notable recent coverage proving its progress in the modern media landscape, highlighting its boygenius cover story. Even beyond the band's control ("I bristle at the idea of being like a neo-lib wet dream of a girl," Dacus told The Pitchfork Review podcast), boygenius became a yardstick of one's taste and even one's progressivism.

The more cynical listener could take all this "we're so in love with each other" flair as bait for people who spend too much time online. But that kind of skepticism could just as easily arise from classic sexism, the kind of old-school critical bias the boygenius operation is directly critiquing. (It's right there in the band’s name, in the suits they wear onstage, and in lyrics like "Always an angel, never a god.") Still, the self-importance some listeners projected upon the group could feel like overkill. At its worst, like when a few viral Reddit posts highlighted some extreme gatekeeping among boygenius fans, the response to the group mirrored the cartoonish extremes of modern pop fandom.

It's fair to wonder whether any of their peers will be able to follow them to that level of stardom. They are a story of three hard-working artists paying their dues, gradually cultivating success, and finally being rewarded for their patience at a time when it feels more difficult than ever to be an indie musician.

This year the music industry revealed more of its long-existing cracks to alarming degrees. The kinds of far-reaching music publications that originally championed Baker, Bridgers, and Dacus continue to shut down — replaced, if at all, by isolated newsletters or podcasts. It's become increasingly impossible to make any money from touring unless you're operating at Swift's scale. Music discovery platforms with an artist- or album-first approach are still getting hit hard, while the dominant streaming apps like Spotify and TikTok continue to move away from supporting new artists and more towards general content.

Which raises the questions: Will the Big Indie ecosystem be able to produce another boygenius? Will any scene outside the control of major labels and big tech have the means to develop new stars — or even to support a sustainable career for artists beyond the 1%? If the same structures and pathways that allowed Bon Iver, Japanese Breakfast, the War On Drugs, and countless others to level up have disappeared, what, if anything, will take their place? Will the next boygenius only be possible by getting lucky and going viral?

Those concerned about how the next boygenius can break through include boygenius. At our lunch, that topic turns into a conversation about Bandcamp, which went through recent brutal layoffs after its second sale in as many years, versus Spotify, which continues to seemingly cater only to the 1% of music's top earners, versus TikTok, a hot mess. The trio is at its most fired up discussing the subject.

"I love Bandcamp," says Dacus, reflecting on releasing her first music through the music, merch, and editorial platform in high school. "A lot of really great writing has come out of Bandcamp. I'm not familiar with what changes are going on, to be honest, but I thought it was sick that they did stuff like Bandcamp Friday, which benefited artists. And Spotify's response was to let fans tip — a widget for tipping. But what did Spotify do personally? What I hope is that the anger will show the desire for infrastructure and more people doing the administrative task of setting up a new system. That's hard because not everyone knows about tech. I wouldn't know how to do it. But kids need to be able to put their music up for them and their families somewhere. On Bandcamp, you just click 'upload.’"

Baker and Bridgers echo the sentiment that having viable options for DIY musicians is necessary. Dacus' debut LP, No Burden, was funded on Kickstarter. In Baker's previous band, the Star Killers, she asked for $700 to finish a record on Indiegogo — and got ripped apart in her music scene for requesting financial help. "Who's going to help you write a grant, or do you have a family friend who's gonna bankroll you?" Baker asks. "People that don't have that need to use Bandcamp."

Baker offers that there is always a power vacuum in the music industry, from the domination of old Tin Pan Alley contracts to the power consolidation of record labels throughout the CD era to our present age of streaming platforms. It's an interesting question: Is Spotify uniquely problematic, or is it just wielding the control record labels used to? What is even the function of a label in 2023 — especially, as Bridgers suggests, when you need to take off on Spotify just to get signed in the first place? Dacus grounds the problem in a bigger picture. "You could have such sick music, you could have a community, you could be doing shows and love it, and it's still something that doesn't coalesce," Dacus says. "I have friends that ask how this year feels or how it happened, and I'm like, honestly, yeah, I think the music is good, and I've been working for a long time, but you can do those things and it's still not happening. There's that mystery element. No one is entitled to it, so selling a promise is not cool."

According to the trio, the bigger culprit in selling that false promise is TikTok. The app's payments are negligible, Bridgers says, and artists can only hope that exposure there leads to earnings on other platforms. "If you can get traction on your own via DSPs such as Spotify," she adds, "you will have more power when it comes to finding a label partner."

"I feel more about that with every platform," Baker offers. "This is projecting itself to be a neutral space or to be a virtual recreation of a community conversation that actually is not real because it is crafted to generate revenue for itself. Every time you give self-expression but not to another individual … when you release morsels of yourself that are curated to be then passed around per marketability to different demographics without you even seeing the pulleys and levers, that is unfair to a person seeking connection and is getting back a twisted funhouse mirror reflection of what their world looks like. That is actually evil, and you do it for free, and someone makes money off of your effort and your genuine pouring your heart out into something."

"The system is broken," Bridgers continues. "This is no judgment on people who use it. It's just the premises: The system is evil and taking advantage of you."

"Show us one interview where it doesn't come to this," Dacus says without skipping a beat, as everyone laughs. "This is just what you're signing up for!"

Baker connects these observations to her earlier Kafkaesque point: These platforms let you say whatever you want because they know they won't actually have to respond to those criticisms with change. "Sometimes I feel like a guy outside the Capitol building with a megaphone and everybody's like, 'There goes crazy Baker.’"

"The tinfoil hat genius," adds Bridgers.

Back to Halloween at the Bowl. Back to "We're In Love." I'm in awe of this performance. As I take it in, I think about my conversation with Baker, Bridgers, and Dacus about indie music's unknown future. It sounds like we all share the same hopes and frustrations. We left our lunch not quite knowing what to do next or what the best solution could even be. Everyone invested in the idea of indie music wishes they could see a way forward. But it's not boygenius' job to fix the music industry. It's their job to make listeners feel like I feel right now.

At this moment, for this song, I'm choosing to be happy. Happy that boygenius get to have their time in the sun (or tonight, the moon), that they get to experience their success in real-time by bringing thousands of strangers together in a sold-out world-class amphitheater. For me, the novelty of being in large crowds again post-COVID-19 lockdowns has worn off, but I am more mindful and thankful for these gatherings. I remember why I loved going to concerts in the first place, an experience I still can't get from other artistic mediums. I remember Leonard Bernstein's famous answer to the question of what music even means: Music is just notes. It's people who give those notes meaning. Boygenius understand this. So does "Justin Bieber," intuitively at least. So do all of us here tonight.

Even if it never happens again, this is a moment. It's a beautiful moment. I hope it continues for as long as possible.

But it does end. This show ends, at least. Boygenius walk off the stage to 100 gecs' "Dumbest Girl Alive," a funny contrast to their walk-on song from a few hours ago, Thin Lizzy's "The Boys Are Back in Town." The meta-ness of it all is silly and compelling, and it feels fitting for a boygenius show: a set that begins with an homage to classic rock's origins and ends with what could be the classic rock of the future. I'm not ready to give up hope for what comes next, but if this is the closing chapter to an important part of music history, it was great while it lasted.

Stereogum is an independent publication supported by readers. Become a VIP Member for ad-free browsing, Discord access, and more.

CREDITS

Photography: Davis Bates

Styling: Lindsey Hartman

Hair: Dita Vushaj

Makeup: Amber D

Creative: Oliver Hartt

Video Direction/Editing: Kirby Gladstein

Video Lighting: Thomas Lotero, Video By Robot

Video Sound: Patrick Hurley

Video Interview: Scott Lapatine