If you're cynical, last summer's parade of country chart-toppers was just culture-war bullshit, with nothing further to read into it. Jason Aldean and Oliver Anthony at least partially scored their hits from an aggrieved conservative impulse to own the libs; to some extent, Morgan Wallen did, too. But something else was happening when Zach Bryan and Kacey Musgraves' duet "I Remember Everything" reached #1 in September. The somber ballad casts Bryan and Musgraves as former lovers, now separated by an unbridgeable chasm of booze and disappointment. It's a song powered not by opprobrium, but by an even mightier force: nostalgia. "Do I remind you of your daddy in my '88 Ford?" Bryan, who was born in 1996, asks Musgraves. Against a bed of dusty acoustic guitar and fiddle, his deep voice crackles with borrowed authenticity.

"I Remember Everything" is a decent song, but its meteoric success seems to speak mostly to audiences' craving for something they perceive as real. It's a craving that's being rewarded more satisfyingly and with more frequency well below the top of the pop charts. At the grassroots level, Americana, folk, and country music are enjoying a prolonged renaissance, with YouTube kingmakers like Western AF and Gems On VHS propelling stark, handmade performance clips to virality. One such clip is Willi Carlisle's 2020 performance of "Cheap Cocaine" for Western AF.

In the black-and-white video, Carlisle walks through deserted city streets, playing guitar and harmonica, singing about partying at a punk house and staying up all night. The song has a twist that undermines any outlaw bravado – the narrator calls his mom to tell her he's had enough – but it's clear that Carlisle has lived the words he's singing. He's since parlayed that song's success into a couple of critically acclaimed records, most notably 2022's subgenre-agnostic Peculiar, Missouri, and a fruitful touring career as both a headliner and go-to support act for artists like Sierra Ferrell and Tyler Childers. But if you aren't tapped into underground Americana and you've heard of Willi Carlisle, there's a good chance that "Cheap Cocaine" video is why. He's ambivalent about that.

"While I was opening for Sierra Ferrell, somebody was like, 'Man, I love that cover of that one song you did,'" Carlisle laughs. "And that's how you know that you have a small hit, right? I want them to see the other side of that a little bit."

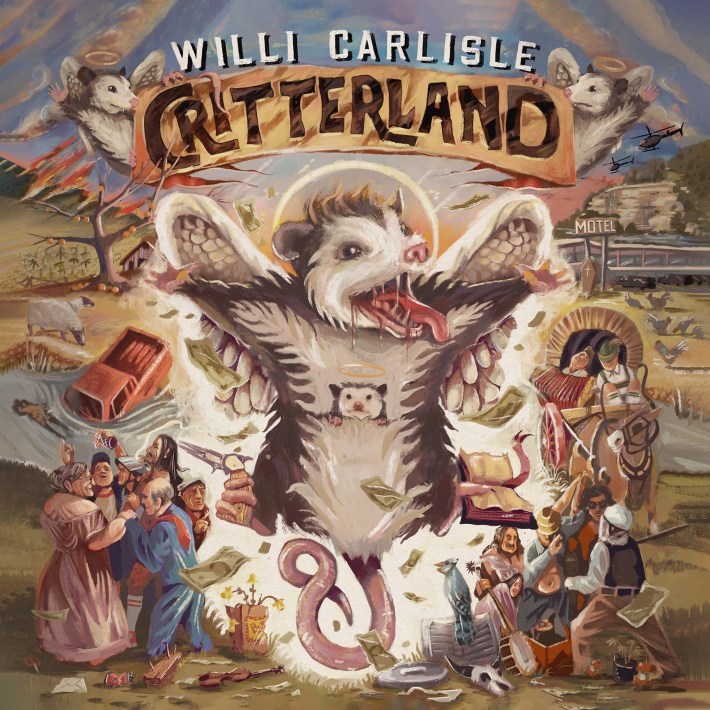

That "other side" is presented vividly and unapologetically on Critterland, Carlisle's third full-length. On "Dry County Dust," the narrator returns to his childhood home while trying to kick addiction, beset by dopesick shakes and looking for redemption. "When The Pills Wear Off" is a devastating song about losing a friend to a fentanyl overdose. "The Money Grows On Trees" transforms the narcocorrido into a hymn of desperation about small-time dealers clinging to the edge of the world. The album presents drugs and addiction as simple matters of fact, as nonnegotiable as the sky or the ocean, unblemished by romanticization or sanctimoniousness.

"I've reached the age where the hard drugs have killed some of the people they were going to kill, and I wanted to write songs about their lives, but also about my own, that I hadn't yet," Carlisle says. "There was some sense that I wanted to get them out of the way. Here, entering my mid-30s, I don't want to write about the mistakes I made in my early 20s and mid-teens all the time. There's some sense of laying it to bed by saying it totally honestly and earnestly."

Carlisle's songs are penetrating, sharply observed, and unflinchingly specific. They're also built on sounds that have been handed down for generations. Critterland finds Carlisle singing in his languorous Ozark drawl, playing guitar, harmonica, banjo, button-box accordion, and fiddle. Producer (and Americana legend) Darrell Scott adds mandolin and lap steel. For some number of people at a Willi Carlisle show, hearing folk songs played beautifully on all those old instruments is enough. That makes him wary.

"I think BJ Barham from American Aquarium said, '99% of my fans, I would love to have a beer with,'" Carlisle says. "I think the 1% that are dangerous, to me, are the ones who will just applaud if I pick up a fiddle. If I take that as truth, that would be really incorrect. It's not just about picking up the fiddle. It's what you do with it."

"I worry sometimes," he continues. "I've been thinking a little bit about the American primitivist, maybe you could say 'cottagecore' movements, and worry that they are plugging into, or will eventually plug into, a latent sense of American right-wing nationalism that we haven't really seen that much yet. Oliver Anthony, for example: I remember reading something that said, 'Johnny Cash is back and he's playing an old Gretsch Resonator.' If Oliver Anthony is considered, 'Oh, thank God, finally, another Johnny Cash,' well, then we're in trouble, because Oliver Anthony is just a guy, and playing an old Gretsch Resonator is not a real thing, even. It's like playing a budget guitar that's designed for people that are peddling in that kind of nostalgia. Unless we're very careful with this, people will leverage it to bolster a sense of right-wing nationalism and white identitarianism."

Carlisle's music wouldn't seem to run the risk of being co-opted by the far right. For one, he's an agitational, antifascist folkie, in the Woody Guthrie tradition. He also weaves his queerness into the music in a way that makes it clear who he is, and who he stands with. At first, Carlisle was frustrated by being pigeonholed according to his identity; a lot of headlines about "Queer Singer-Songwriter Willi Carlisle" made the rounds, especially around the release of Peculiar, Missouri. That makes some sense. "Life On The Fence" is a heartbreaking waltz about queer desire and self-denial, one that "I Won't Be Afraid" answers with a mantra of self-acceptance. But there were plenty of other songs on the record, too, about itinerant magicians and water rights and semi-homelessness, and coverage of the album sometimes glossed over those. Lately, Carlisle is feeling more at peace with how he's written about.

"Most of my complaints are, like, 'We had to survive moderately stressful conversations on social media and moderately stressful interviews.' That's about it. The complaints that I had, I dismiss them entirely myself," he says. "It's like, what the fuck price are you gonna pay to act like yourself? That's OK. One thing that made me really grateful is that it helped me find my audience, and a deeper connection with people for more specific reasons, reasons that are not monolithic. And that's the nice thing about queer culture, is that it's not monolithic. You're born that way, but you're not born into that culture, so we find it and build it together. So that's been actually really positive."

Queerness is a subtler undercurrent on Critterland, but it's always there. Carlisle mused to the Daily Yonder in 2022, "I've showed up queer to every show I've ever played. Does that make them 'queer shows'?" That rhetorical question colors the writing on Critterland, where the existence of sexuality feels as matter of fact as the presence of drugs. Overall, Critterland feels a little more writerly than Peculiar, Missouri — or anything else Carlisle has done. The genre exercises of Peculiar, which saw Carlisle darting from honky-tonk to conjunto to talking blues, have been replaced with a more consistent authorial voice.

"There's fewer digressions into pure folklore on this one, for sure," Carlisle says. "I wanted to make something that was closer to the kinds of records that people like Darrell Scott or Guy Clark made, which are records that showcase the writing primarily, and that are less tied to genre. I think this is probably more of an Americana album than a folk album, compared to Peculiar, and that's OK with me."

The tonal consistency helps make Critterland feel like a slightly stronger record than Peculiar, but as of our conversation, Carlisle still wasn't sure how he felt about it. That's not a slight against the material, he swears. He's proud of the songs, but he's just not sure how he feels about making records in general.

"The studio is the final frontier for me," he says. "I was born to play folk songs at the fucking farmer's market. That was all I wanted to do, for years. I wanted to call square dances and stuff. So, surrounded by technology, and having to make split-second decisions, and also performing in what's essentially a sterile environment — it's not sterile, that's why you have other creative people with you, but compared to a live audience, it will always feel a little sterile. I think with every creative person, it's not so much doubts as a hunger for the new. 'If I could say it again, I would say it different. Knowing what I know now, I would blah blah blah.'"

"I'm a performer," he continues. "I'm also in showbiz. I love showbiz. If I could think of myself more as a traveling vaudeville guy, I would probably have a greater degree of comfort with this."

Carlisle's raucous live show confirms that characterization. When I saw him headline last year, he was the only person onstage, more in a one-man band sense than an unaccompanied singer-songwriter one. He was as convincing on guitar and banjo as he was clacking sets of cow bones together, or singing off-mic at the top of his lungs like a street preacher. ("I believe in doing what the instrument is laid out for. I don't really believe in virtuosity," he says.) Most of the tunes in his set came with a story, or an explanation of a historical song style. It's the folk gig as tent revival — fittingly, given that most sets end with a singalong of Peculiar highlight "Your Heart's A Big Tent." Despite the communal nature of his shows, Carlisle takes pains to ensure that they always feel intimate. It's a challenge he's acutely aware of as he looks forward to a summer of opening for Tyler Childers in 20,000-seat amphitheaters.

"I don't necessarily think that a modern concert is the best way for us to do the spiritual work that I think music should do. I really don't," he says. "In fact, I sort of think that an amphitheater might be one of the worst ways to do it. The most impersonal. The population of medieval Paris crammed inside of one space. Sometimes it feels like a refugee crisis more than it feels like a concert. So, I'm curious. I'm staying curious about how that will feel."

The songs he'll be playing on the amphitheater tour certainly weren't written for that kind of stage. "When The Pills Wear Off" isn't likely to inspire one of those big Zach Bryan shout-alongs. But as dark as Critterland often is, it's also defiant, and defiance can be its own kind of luminescence. Carlisle wrote a couple of more lighthearted songs for the record, but they didn't make the final cut. The Critterland we got instead feels relentlessly true, and it asks us to sit in the discomfort of its most difficult truths. It's an album about acknowledging how hard shit can be and moving forward anyway.

"As I was trying to make the record, initially, I kept trying to find places where I could let bits of light in," Carlisle says. "I wanted this world, this Critterland, to brim with possibility. I think it still does, but those little points of light got replaced by more songs about death, dying, drugs, suicide, and stuff like that. I knew when I was writing a lot of those songs that this record was gonna be one about choosing to live, even if things were difficult, and choosing to be yourself, even if that was difficult. And I do think it still says that pretty loud and clear."

Critterland is out 1/26 on Signature Sounds.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!