Todd Fink basically invented Indie Sleaze and all he got was a public nudity charge.

Let's backtrack to 2002. The Faint were a year removed from their landmark third album Danse Macabre, getting courted by Capitol and Rick Rubin and opening for No Doubt, a band striving to wipe away the image of goofy ska-pop that lived on in Fink's memory. As these things tend to go, being a support act for an arena tour was both an honor and a daily humiliation, as the Faint took on either disinterested or non-existent crowds with a volume limit, five minutes of soundcheck, and a generic light show, if they got one at all. And that's before the pranks of the tour's final night; No Doubt's crew boobytrapped the stage with curls of exposed duct tape and put a 100% delay on Fink's vocals, leading his frightened bandmates to think he was intentionally sabotaging the gig by singing everything a second behind the beat. Also, someone ran on stage dressed as a giant penis.

And so the Faint fought back the only way they knew how: "We spraypainted our genitals and wore catering napkins over them," Fink beams during our Zoom conversation. They bumrushed the stage during "Just A Girl," at which point a baffled, but apparently game, Gwen Stefani handed Fink the microphone because she didn't know what else to do. Fink then yelled "I'm just a boy! I'm just a boy!" during the chorus which didn't bother No Doubt as much as it did the pueblo government and law enforcement officials in attendance at the Santa Ana Star Casino. Fink wasn't convinced that the Faint had picked up many new fans during this tour, but he had at least a few important ones in his corner - after undercover cops took him to an Albuquerque jail, Stefani apparently helped bail him out and he signed a couple of mugshots for the police upon his release.

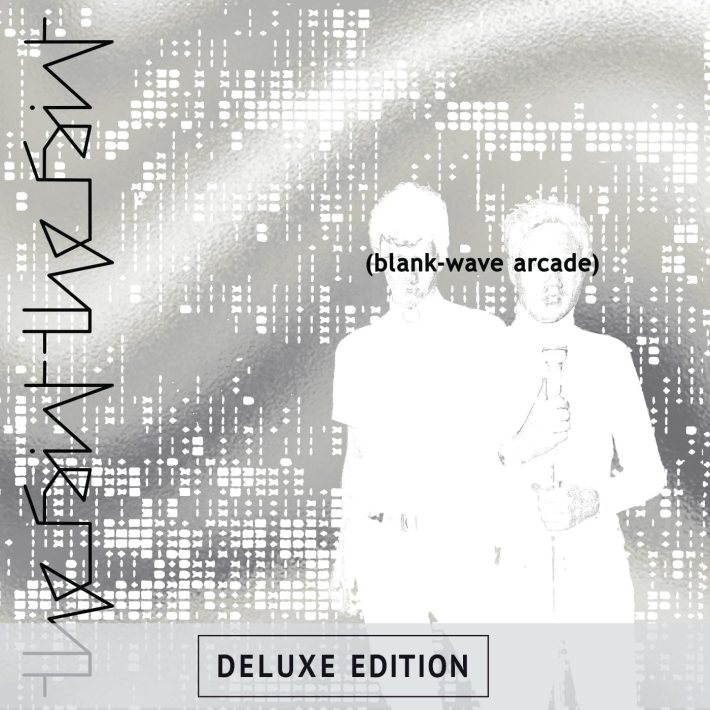

This was Fink's first and last time in the pokey, so his extralegal antics were merely a symptom of the Faint's brush with fame, not the cause. This era is bookended by 1999's Blank-Wave Arcade and 2004's Wet From Birth, both of which are being given deluxe reissues this Friday. Fink feels this process has given the band a renewed jolt of energy as they slowly hash out their first proper studio album since 2019's Egowerk. But that's just a nice byproduct of Fink's main motivation to have their full catalog back in print; hence, the otherwise curious exclusion of Danse Macabre, which had already gotten remastered and reissued in 2012.

Regardless, the timing could not be more ideal for a reassessment of these two crucial, yet lesser-renowned entries into the Faint's discography, especially as a wave of self-styled Dimes Square influencers try to force into existence what came so naturally on Blank-Wave Arcade. Only time will tell whether anything from the new era of Indie Sleaze will produce anything as truly true to the genre's vision as "Sex Is Personal," but I'm not holding my breath.

For his part, Fink is vaguely aware of the existence of "indie sleaze." When he asks for me to explain its stylistic boundaries, I regretfully inform him that I've seen Spotify playlists including "My Girls" and Vampire Weekend. "Blog era then," he laughs. He isn't particularly interested in claiming any kind of godfather status to the Dare or Fcukers or what have you, any more than he was interested in fitting in with any scene, save for the Saddle Creek collective from which the Faint arose.

In the mid-'90s, Saddle Creek and the Omaha indie rock scene in general were a fascinating curiosity - a self-sustaining, artistically incestuous collection of very young artists thriving in a city that had next to no pop culture imprint before then. Omaha, as Adam Duritz put it several years earlier, was "somewhere in Middle America," and that was about it. An early, more indie-leaning incarnation of the Faint was known as Norman Bailer and featured a teenaged Conor Oberst, while Fink played mandolin in the suit-wearing folk-rock outfit Lullaby For The Working Class, led by Ted Stevens of Cursive and featuring Saddle Creek house producer Mike Mogis. It only gets more tangled from there.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

1998 was the first, but certainly not the last, banner year for the label. Bright Eyes released their breakthrough Letting Off The Happiness; Cursive followed suit with their second album, The Storms Of Early Summer: Semantics Of Song. Though each would soon reach far greater heights, the Jordan and Pippen of Saddle Creek were established. Tim Kasher was the post-hardcore agitator, while Conor Oberst emerged as a generational voice, a potential "new Dylan" who presaged the social media era with his startlingly candid and fevered lyricism (if you still think the interviewee on Fevers And Mirrors is actually Conor Oberst, it's Todd Fink doing a dead-on impression). Amidst all of this friendly competition, the Faint were a flamboyant wild card, the Dennis Rodman if you will.

Prior to Blank-Wave Arcade, Fink had worked at a record store, a quintessential "band guy" day job that was still physically taxing due to his rheumatoid arthritis. After an unusually bad flare up, Fink called in sick, something he never had done up to that point. "I just sat there on the couch thinking about my life and decided, ‘You know, I'd rather eat three saltine crackers with some ketchup on them with some water and just do what I want to do all day with my time," he recalls. "And so I called [the record store] back a couple hours later and said, you know, I'm permanently not coming back." The Faint was playing "basements and taco shops" to that point, but 1998 Omaha was a livable place even for an unemployed musician; the monthly payment for Fink's four-bedroom house was $138, split equally amongst four roommates.

And so, Fink could now fully invest in his radical vision for the Faint: "I don't want to speak for the whole band, but I think the mindset, for me at least, was to escape indie rock, find what's happening in the future and go there." Though they'd be most often compared to early Depeche Mode or Gary Numan, Fink's aspirations were, "underground Berlin music, because that's where I thought the future was made, also in Tokyo." Shortly after the release of their 1998 debut Media, Fink wrote "Sex Is Personal," the band's first signature song and the foundation for the more synth-forward, stylish presentation to come. Fink recruited the late keyboardist Jacob Thiele from an Omaha post-hardcore band with the extremely post-hardcore name To Repel Ghosts; this would not be the last time the Faint tapped into their city's gnarly underground, as they brought in Dapose for Danse Macabre, a guitarist who had most recently played in a death metal band. Though this staffing process might appear counterintuitive for a band often compared to '80s synth-pop acts, it's a reflection of Fink's admiration for San Diego's late-'90s noise-rock scene, which included both the Locust and a pre-DFA the Rapture.

"The Faint have created one of the first records that's equal parts '80s new wave and garage rock. What're you gonna say about that? It sounds fuckin' awesome!" These are the words of Pitchfork founder Ryan Schreiber on Blank-Wave Arcade, though the Faint would receive much rougher treatment going forward. The ensuing 26 years gave us electroclash, dance-punk, dance-rock, several iterations of New Wave revivalism, and five more the Faint albums, so it's a bit harder to appreciate just how startling Blank-Wave Arcade was in 1999. But you have to remember what indie rock was truly like back then. "You don't use fog machines, and you don't go to bring your own garden lights, you don't do synthesizers," Fink explains. "Synthesizers were for cover bands that were still trying to do late '80s tunes." Though the Dismemberment Plan had called out the arms-crossed, stone-faced indie rock stereotype on "Do The Standing Still" two years earlier, they were goofy and genial, clowning themselves as much as their fans. Blank-Wave Arcade was a work of antagonism from top to bottom, most of all in its subject matter.

Of the first five songs, three have the word "sex" in the title. "Using the word ‘sex' in songs is like, you're going there, which at the time in indie rock, you don't go there," Fink notes. Yet, none of them are sexy. "Sex Is Personal" traces the awkward first steps in trying an open relationship. Though "Worked Up So Sexual" takes place in a strip club, like many of the Faint's songs, it's about the ways people exploit power imbalance. Fink's vocals, flat in delivery yet sharp in tone, were perfectly designed for his assumed role as an omniscient, and often cynical, narrator. Paraphrasing David Byrne, "I'm just pointing out things that aliens might recognize about humanity."

For all of the positive buzz around Blank-Wave Arcade, Fink's confidence wavered as the Faint plotted their next steps. "Now that you got everybody's attention, do you suck?" he wondered, worried that he'd hit the sophomore slump on what was technically their third album. "I felt like we didn't have another 'Worked Up So Sexual,' to be honest. But people liked it anyways."

By the time The Faint released Danse Macabre in August 2001, all of a sudden it was a bunch of fashion victims from New York City trying to catch up with what was happening in Omaha. There was the rise of DFA and electroclash and Vice, all of which was deemed as a necessary counterbalance of trashy hedonism in the wake of 9/11. But as Tom Breihan wrote in the 20th-anniversary remembrance of Danse Macabre, compared to A.R.E. Weapons and Fischerspooner, "The Faint were different, and you could feel it in the air."

It's not just that they were from Omaha or that they were turning down the overtures of major labels. "Our Fugazi won out," Fink shrugs, still questioning whether they made the right choice in prioritizing underground idealism over the careerism that was blooming in indie rock at the time. Besides, the Faint were every bit as intentional about fashion as any Pratt or FIT student. "I feel like I could be a video editor or a poster designer or a clothes company designer or something, it just happens to be that I am doing music," Fink explains. True to form, Fink looks way too cool for a Saturday afternoon being spent in his own house - his face framed by flowing, blonde hair, he's wearing chic sunglasses, a bandana around his neck and a hat that looks very similar to the ones that Fink will make with his own hands for $475. He's surrounded by an armada of synths in a home studio with a blaring High Desert sunlight in the backdrop, as he and his wife, Orenda Fink, "panic bought" a place near Joshua Tree after leaving Omaha.

Still, it was, and still is, clear that the Faint were an art-punk band that happened to work within fashion and radical politics, rather than the other way around. This continued to hold true when they released Wet From Birth, still the most divisive album in the Faint's catalog. If Blank-Wave Arcade was the Faint as their most minimal, still on the cusp of finding their sound, Wet From Birth is the opposite, taking their Faint-ness to maximalist extremes. The opening "Desperate Guys" begins with a violin solo nicked from Paganini's "Caprice No. 5," and then there are the full-on string parts arranged by Bright Eyes utility players Mike Mogis and Nate Walcott. A tribute to his Athens, GA-raised wife, "Southern Belles In London Sing" features acoustic guitars and lyrics sourced directly from Fink's personal life, both of which were inconceivable only three years earlier.

But if Blank-Wave Arcade’s fixation on sex felt provocative, they had nothing on "Erection" and "Birth," songs that often took up the most space in Wet From Birth’s negative reviews. The latter is an extremely graphic rendering of Fink's own birth that he wrote after devouring every single thing ever written by or about Leonard Cohen; "How could you write that about your own mother?" Fink asks rhetorically. He admits that mistakes were made on Wet From Birth - it's a little too serious, maybe too musically cluttered. Still, he stands by the spirit that went into making their most abrasive record at their commercial peak. "I don't like the idea of trying to make music that you think people will like, because you're making a lot of assumptions and trying to read minds," he says. "If you fail, also, you failed them and you failed yourself. It's just a double fail."

By no means is Wet From Birth a failure; I think of it as their Worlds Apart, a band reacting to their masterpiece with an uneven but wildly entertaining follow-up that has proven to be quite resilient in video games and ad campaigns. And despite the Faint taking an average of five or so years between new albums, they always seem to kill it every time they pop up at festivals. "You have to be brave enough to be actually saying something that people will react to positively and negatively to have anything really happen," he states, at once a challenge to up and coming artists and himself as the Faint ready an album that will compete with a generation of artists they directly influenced. "Just the decision to be okay with doing something you know that some people will hate, that type of approach is rewarded by the Matrix."

The Blank-Wave Arcade and Wet From Birth reissues are out 3/14 via Saddle Creek.