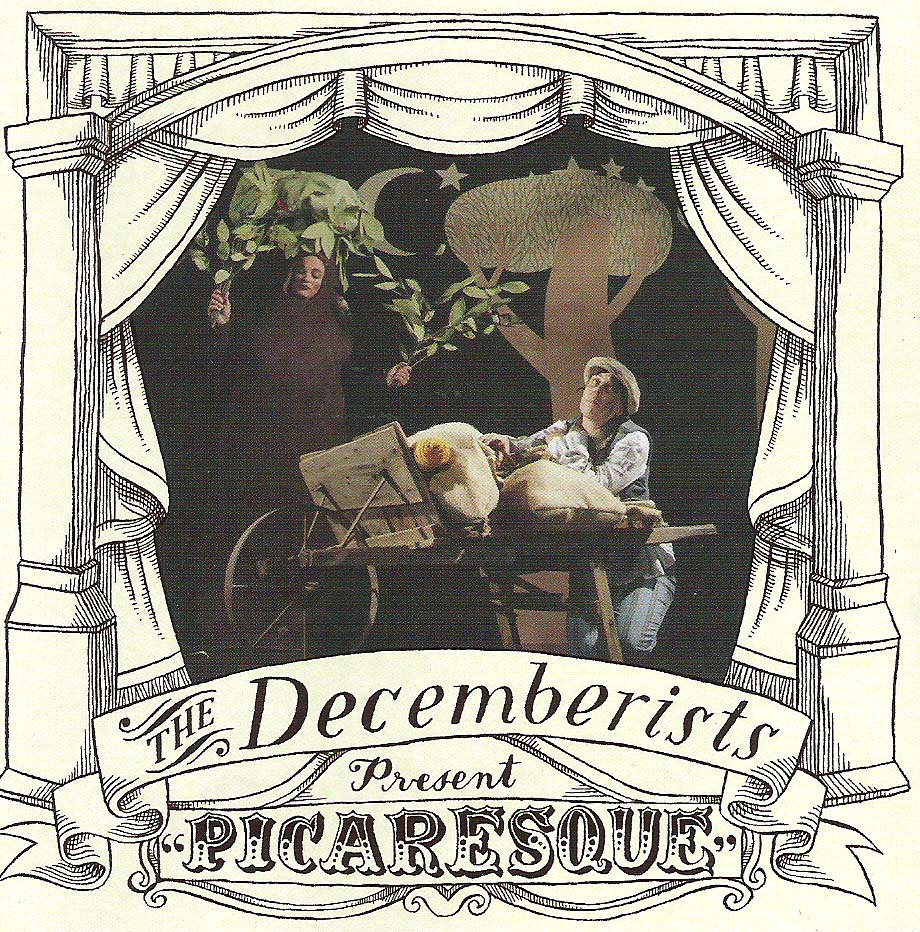

- Kill Rock Stars

- 2005

When I saw the Decemberists play NYC venue Webster Hall in the fall of 2005 — a little over six months after the band released their third album Picaresque — there was a sense that Colin Meloy and his highly whimsical crew of Portland-hailing folk-rock myth-makers were on the type of career trajectory that bands of their ilk can only dream of. You could quite literally feel it in the room, as Meloy dropped some mid-set banter about how major-label folks were hanging out in the upper balcony that constitutes Webster's VIP area; his tone while doing so was a little sneering and more than a little self-effacing, but also grounded in an appreciative reality of the situation.

If you were in attendance, you got the sense that he already knew what was coming next: a step up to the music industry's supposed big leagues, which is exactly what happened when the Decemberists released their fourth album The Crane Wife in 2006 as their inaugural bow under new label home Capitol. "I felt like I was following in the mode of the bands that I loved," Meloy told me while revisiting the Webster Hall comments for my newsletter last year, citing prior indie-to-major acts like R.E.M., the Replacements, and Hüsker Dü as career inspiration. "They waited until they had a pretty sizable fan base so that switching to a major label wouldn't affect what they did."

If The Crane Wife represented a logical next step for the Decemberists in terms of their career, then Picaresque, which turns 20 years old this Saturday, captures Meloy and Co. on the precipice of something greater — a snapshot of a band in the midst of collecting admirers like a katamari rolling across the indie-pop landscape before occupying a different cultural space entirely. But Picaresque also stands as the greatest distillation of the Decemberists' powers to date, their strongest collection of tunes representing an inarguable peak in their 2000s run. It's the easiest Decemberists album to love, with all of the band's 12-sided eccentricities sharpened to maximum effect and Meloy's melodic gifts ringing out with pure clarity. If you ever hear someone ask, "How did this band get so popular, anyway?" feel free to point them in this album's direction.

Picaresque arrived at what remains as the Decemberists' most impossibly prolific creative period to date; just a few years before, the band had emerged from the Pacific Northwest with the one-two punch of 2002's windswept debut Castaways And Cutouts and the sturdy follow-up Her Majesty The Decemberists in 2003. At the time, it felt a bit like they came out of nowhere, especially since Castaways arrived just before the era of buzz-building mp3 blogs had truly taken hold in establishing indie rock's arguable imperial era. Pitchfork — which was then settling into the beginning of a decade-plus run as indie's fickle kingmaker publication — lavished praise on Castaways as well as most of the band's 2000s output, with critic Eric Carr bookending his review of the album in specific by comparing Meloy to mythical Neutral Milk Hotel frontman Jeff Mangum.

The comparisons, as comparisons often go, were skin-deep at best. Sure, Meloy and Mangum shared nasal vocal affectations, a predilection for multi-suite folk songs with esoteric trappings, and the occasional song written from the perspective of a deceased woman — but the Decemberists' songcraft was far too traditional in nature, miles away from the psychedelic freak-outs that Mangum and his Elephant 6 cohort were known for, to accuse one of being the mirror image of the other. If anything, the Decemberists were closer in tone and tenor to what John Darnielle would eventually establish with the Mountain Goats; literary-minded story-songs with ornate arrangements and lyrics written in what The Royal Tenenbaums’ Eli Cash would refer to as "an obsolete vernacular."

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

The greater truth is that, in the early-to-mid-2000s, the Decemberists made for an ill fit when scoping out the landscape of indie rock in general; PacNW colleagues like Death Cab For Cutie and the Shins were working in a more straightforward vein of indie-pop, while much of their Kill Rock Stars labelmates at the time (Deerhoof, Sleater-Kinney, Comet Gain, Gravy Train!!!!) leaned more experimental and abrasive in terms of the sounds they were creating. "There was a 'rising tide raises all boats' sort of thing, and we were carried along with that," Meloy (who's never met a nautical comparison he won't resist) told me last year while reflecting on the Decemberists' initial ascent, professing points of inspiration like Belle And Sebastian's epochal '90s indie-pop classic If You're Feeling Sinister for that time in the band's career.

Similar to B&S' cultish rise in the '90s and 2000s, the Decemberists' music felt like an increasingly badly-kept secret, with Castaways and Her Majesty as evidence of Meloy's ability to write heartfelt and easy-to-love melodies that felt as if they'd existed in your head forever upon hearing them. But both albums also felt like collections of songs (by and large, really good songs) rather than true front-to-back artistic statements, which made Picaresque’s arrival all the more momentous. The record felt and still feels like the Decemberists' version of a blockbuster effort, showcasing the band's most dazzling arrangements and Meloy's most immediate melodies to date; if you drew a line between the two halves of the band's still-going career — the unlikely-indie-heroes early days and the folk-adjacent fandom they enjoy today — Picaresque sits squarely on it, with plenty for both sides of the divide to take pleasure in.

Even as Picaresque notably features the Decemberists' sweetest-sounding and most winsome melodies in their catalogue, the record ironically opens with a stormy portal of a trio of tunes, gesturing ever so slightly towards the prog-rock trappings they'd soon turn to in the latter half of the 2000s. "The Infanta" kicks the record's doors open with wolf calls and pounding drums, while "We Both Go Down Together" and "Eli, The Barrow Boy" respectively tilt the scales towards lurching sea-shanty fist-pumpers and forlorn plague-age balladry. Such sonic touchstones would later and decidedly become features, rather than bugs, of the Decemberists' aesthetic mainframe, but on Picaresque they're more presented as evidence of what the band was capable of and where their true interests might lie.

The big highlights on Picaresque are unquestionably the finest moments in the Decemberists' discography; "The Sporting Life" sounds ripped straight out of Stuart Murdoch's playbook from the song title on down, with pinwheel pre-chorus instrumental breaks that burst through the song's shuffling strum in dazzling fashion. The sprightly and infectious "16 Military Wives" represented the band's first toe-dip into political waters that they'd occasionally bathe in throughout the 2010s, with its lyrical criticism of Bush-era imperialism and the rise of American infotainment accompanied by a very of-its-time Wes Anderson-recalling video (directed by Mandy screenwriter Aaron-Stewart Ahn, no less).

Appearing deep in the album's back half, "The Engine Driver" and "On The Bus Mall" feel like what not only the rest of Picaresque but the entirety of the Decemberists' career thus far was building up to. The former is an aching slice of Morrissey-indebted miserabilia so emotionally effective that you barely notice Jenny Conlee's very un-Morrissey accordion wheeling about in the background, while the latter's luscious strum and dewdrop guitar lines are practically the closest the Decemberists have come to making a shoegaze song. Together, the two songs represent a rope-a-dope combo that makes for undeniably potent sequencing.

Of course, anyone who's spent a fair amount of time with Picaresque knows what comes next: the album's penultimate track "The Mariner's Revenge Song," an eight-minute opus that's exactly what it sounds like, bringing the slight shanty fixations of the album's opening third into full and exhausting view with a climax that builds to a "Hava Nagila"-esque stomp of a finish. Remember that demarcation line I mentioned before? "The Mariner's Revenge Song" is the exact point in the Decemberists' career where many either decide to join them in what's to come or get off the boat at the next point of harbor. Personally, when they performed the song on the Picaresque tour — complete with props and a massive whale cutout mimicking the song's nautical battle — I remember mentally dissociating for the duration, smiling and nodding so that no one would think I was turning my nose up at what was taking place.

It's moments like "The Mariner's Revenge Song" that have earned the Decemberists what might be called an unfortunate reputation amongst some indie-minded listeners past and present — especially when you regard what followed in its wake. The Crane Wife and its divisive follow-up, the highly conceptual 2009 LP The Hazards Of Love, went full-bore in terms of prog-folk storytelling and separated the casual listeners from the true believers. Since then, the Decemberists have maintained a very loyal fanbase less situated in the trappings of "indie" (a culture of music listening that has also changed in myriad ways since Castaways first hit record shelves) and more in the mainstream-niche and purchasing-powerful fandoms of nerd culture. The band's latest album As It Ever Was, So It Will Be Again from 2024 closes out with their longest song to date, the nearly 20-minute psychedelic odyssey "Joan In The Garden," and perhaps the most surprising thing about it is that it took the Decemberists nearly 20 years to release a 20-minute song. (The Tain, a five-part story-song EP that the band released a year before Picaresque, clocks in at a comparatively lean 18 minutes.)

But the Decemberists' egghead specificities have perhaps also been overstated in the 20 years since Picaresque. Amidst the conceptual ring-grabs and antiquated instrumentation, Meloy's work has often shone best in the band's most straightforward moments. There's the disarmingly pretty The King Is Dead from 2011, the easy back-to-basics jangle of As It Ever Was (which, to my ears, is their best record since Picaresque), and the all-timer "Lake Song," which stood as the crown jewel from 2016's ambitious What A Terrible World, What A Beautiful World. These two sides of the Decemberists — the nakedly gorgeous and the tempestuously complex — have since waged war on the band's albums themselves, but on Picaresque they formed a perfect union that hasn't lost an ounce of luster to this day.