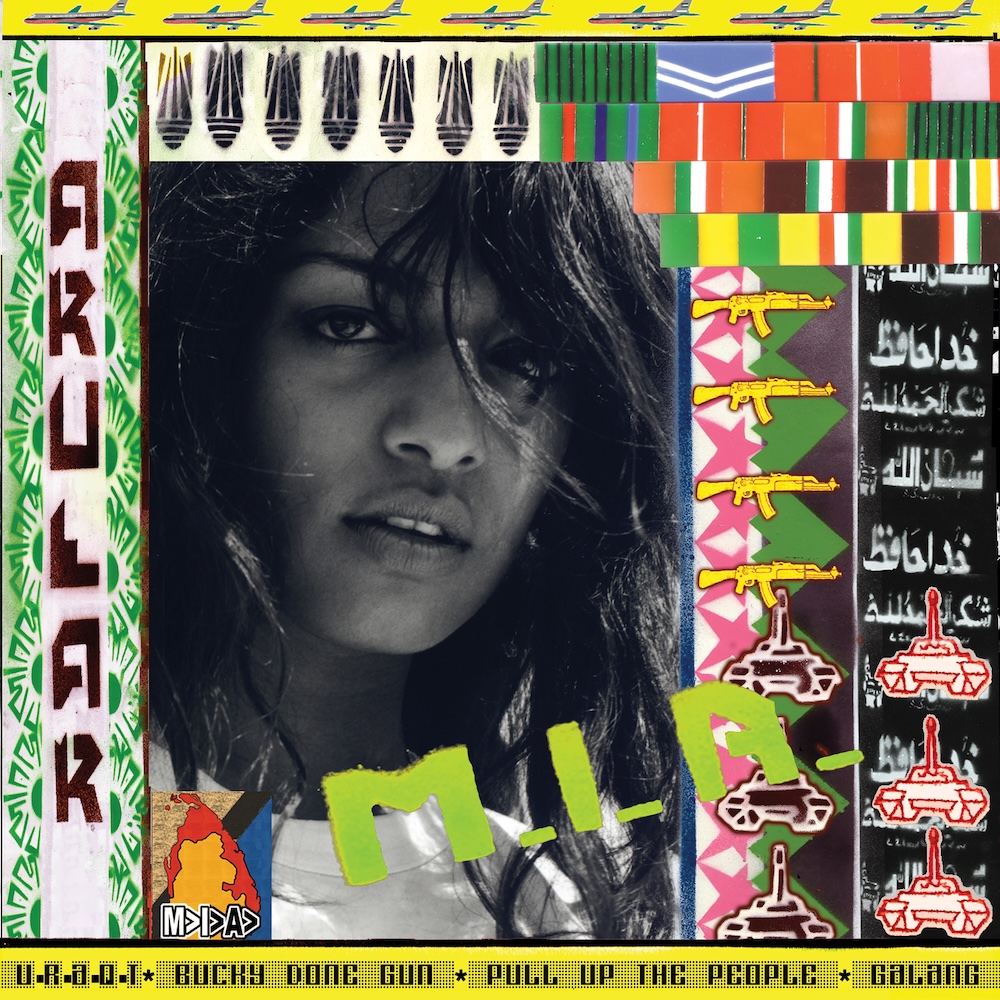

- XL/Interscope

- 2005

Don't try to reconcile it. You can't, and it ultimately doesn't matter. M.I.A. was the most exciting young artist in the world two decades ago, and now she hangs out with Alex Jones and hawks clothes that are supposed to block 5G signals. It happens. There's no natural law that says charismatic young radicals have to age into middle-aged reactionary cranks, and plenty avoid that fate, but it's still a well-trod path. M.I.A. wasn't the first great artist to get fucked-up and spun-around, and she won't be the last. Don't let that spoil your appreciation for Arular, the joyously provocative energy-blast of an album that will celebrate its 20th anniversary on Saturday. M.I.A. the person might be a lost cause, but Arular is forever.

M.I.A. is so good that sometimes I turn the 5G on my phone off for a few minutes out of respect https://t.co/7Mlq6VvOQB

— adam (@kingofthelocals) December 16, 2024

Arular was the right album at the right moment. It landed at the confluence of cultural currents, the most important of which was the endless War On Terror, the campaign of multiple-front atrocities that America carried out all across the planet. Plenty of young Americans marched against the Iraq invasion before it started in 2003, but none of the decision-makers gave half a fuck, and a less-decentered popular culture pushed rah-rah jingoism as America's default setting. Two years of endless death-grind later, even our parents were starting to admit that America blew it, making things worse for the vast majority of human beings in the world, including those serving in our own military.

Another big currrent was the internet and its effects on the listening habits of America's young hipster types. We'd been freed from the tyranny of the CD, and we were waking up to the idea that angular-guitar bands weren't necessarily the only people making exciting music. Thanks to file-sharing sites like Kazaa and the proliferation of MP3 blogs, we could hear the ways all sorts of beat-centric scenes and genres spoke to each other across oceans. American rap, Jamaican dancehall, Indian bhagra, UK grime -- they weren't the same thing, but their circles would overlap in unpredictable ways. On American radio, you could hear rappers and singers discussing their beepers and their bank accounts over samples from Bollywood or Cairo. In Baltimore and Rio, underground producers jacked whatever samples they wanted and transformed those sounds into crude, hard, irresistible dance music. Once you locked in with those party-music crosswinds, the resulting chaos looked a whole lot more exciting than whatever Black Heart Procession were doing -- not that we had to choose between them. Unwound and Missy Elliott records were on the same file-sharing sites, and they could peacefully coexist in our WinAmp players.

People were ready for something different. People were ready for a lot of different things. And then here came this beautiful South Asian girl from London, wielding the language of global guerilla struggle and dripping cool all over hard, immediate beats that pulled from the entire beat-music diaspora without repping for any one scene. When M.I.A. arrived, she was arm-in-arm with Diplo, a DJ whose parties made a big point of their lack of subcultural division. She had a complicated backstory that many of her white fans could barely comprehend, and she presented the idea of subversiveness without fully endorsing any particular political view beyond "stop hunting and killing people" -- then as now, a more controversial stance than it should be.

M.I.A. presented herself as a representative of the global South, but she was also a cool art kid who understood how to drop all the right names. She arrived with a fully developed cut-and-paste visual sensibility and connections to some of the Britpop big dogs from the previous decade. Maybe this was an incoherent stance -- an elite-class hipster preaching revolution while munching on truffle fries. But those of us in her audience were doing the same shit, with the same contradictions. We didn't have to resolve the dissonance in what M.I.A. was doing when we'd barely examined our own biases and fetishes. And anyway, dissonance is fun, and truffle fries are delicious.

So, the backstory. Mathangi Arulpragasam was born in London in 1975 and moved to her parents' Sri Lankan homeland as a baby. During Sri Lanka's long civil war, M.I.A.'s father Arul worked on the side of the repressed ethnic-minority Tamil revolutionaries. I can't presume to tell you much about the dynamics of the Sri Lankan civil war or her role in it. M.I.A. has mostly insisted that her father was not a member of the Tamil Tigers, the left-leaning Hindu revolutionary group who pioneered the use of suicide bombings in their campaign against the Sinhalese Buddhist majority. Instead, it seems that Arul's work was with groups that advocated for the Tamil people politically -- the Sinn Féin to the Tigers' IRA, as far as I can tell. Arul wasn't a pacifist, though, and he reportedly trained with the PLO in Lebanon when M.I.A. was a baby. Arul's political work meant that her family had to keep moving constantly and that her father wasn't in her life much.

M.I.A. has told lots of stories about a childhood living under the constant threat of violence, and no American blogger has yet earned the right to sit here and pocket-watch her trauma. In any case, M.I.A.'s family eventually moved to India and then, when she was 11, back to London. They were political refugees, and M.I.A. has said that she didn't speak English when she first started going to British school. She began calling herself Maya when a relative pointed out that the English kids might have an easier time pronouncing that name. But she adapted, and she excelled. She studied film at St. Martin's College, and she became best buds and roommates with Elastica frontwoman Justine Frischmann. She made videos and visual art and then, eventually, music.

There's some disconnect in there, right? It feels like a book that's missing a couple of chapters. How did a working-class refugee who didn't speak English join the art-school hipster elite? I've never felt like I knew the answer to that one. Surely, talent and drive and charisma played a part in M.I.A.'s social ascent; she has plenty of all those things. M.I.A. shared tastes and sensibilities with the other artsy types that she was meeting. But it's hard to walk into some of those rooms when you haven't been raised specifically to exist in those rooms, and that has always been at the heart of the truffle-fry suspicion that surrounded M.I.A. almost from the first moments of her career. The term "industry plant" didn't exist in 2005, thank god; people would've definitely used it for M.I.A. But that kind of talk shrinks in the face of a great song, and M.I.A. had great songs. Also, she wasn't even that famous yet, so anyone getting too upset would've looked like a weirdo who was trying to ruin everyone else's fun.

M.I.A. came into music as a visual artist. She took the extreme close-up photo of Justine Frischmann's famous lips that Elastica used on the cover of their widely ignored, years-too-late sophomore album The Menace in 2000. (I will happily receive Elastica album number three whenever they decide to make it.) M.I.A. went on tour with Elastica to film documentary footage, and she learned the art of the Roland MC-505 beatbox from Elastica's opening act, the electroclash quasi-rapper Peaches. That makes so much sense, right? M.I.A.'s early music has the same arch lo-res intensity as the best electroclash. As a vocalist, she doesn't quite sing and doesn't quite rap. Instead, she chants melodically and hypnotically -- an approach that owes something to Jamaican dancehall deejays but just as much to the deadpan provocations of electroclash types like Peaches or Fischerspooner or Miss Kittin.

Back home in London, Justine Frischmann lent M.I.A. a 505, and M.I.A. started making beats of her own. Her initial idea was to produce tracks for other vocalists, but when she couldn't find anyone else to sing over her stuff, she tried doing it herself. The result was "Galang," one of this century's great debut singles. M.I.A. recorded the original version of "Galang" at home on a four-track. It's probably no coincidence that the first words of the first M.I.A. song are "London calling," a term coined by the Clash, another act who knew the aesthetic power of the revolutionary pose. (A few years later, M.I.A. briefly became a real-deal pop star by chanting about taking your money over a Clash sample.) The title "Galang" is apparently London street slang for ducking your way out of trouble, but most of the people who heard the track probably just understood it as euphoric gibberish, which was no cause for dismissal. Euphoric gibberish has been a transformative force in pop-music history from the very beginning.

"Galang" is not euphoric gibberish -- not entirely, anyway. M.I.A.'s lyrics gesture in the vague direction of street culture -- shotguns, weed, someone hunting you in a BMW. She describes slipping away from cops and dismisses the societal ideas that you should backstab your crew and that sucking dick will help you. It's a statement of vague resistance, but it hits its climax when language disappears and the "ya ya haaaaaaa" part kicks in. Her beat sounds like lots of things at the same time. It's got the harsh minimalism that the Neptunes cooked up for the Clipse's "Grindin'," the hypnotic whirling handclaps of the Diwali riddim, the fearsome squelching bass-tone of Peaches' "Fuck The Pain Away." It sounds like a symphony of slamming car doors, and M.I.A. moonwalks over all that noise like it's the most ordinary thing in the world. In her delivery, there's at least some ancestral hint of Nico or Serge Gainsbourg or Kim Gordon -- the assurance that sexy boredom can be the coolest sound imaginable.

That cool was already fully formed on the demo version of "Galang" that M.I.A. recorded at home by herself, but it became sharper when she went into a proper studio. She re-recorded the track's final version with the Cavemen, the production duo of Add N To X drummer Ross Orton and -- speaking of St. Martin's College -- the late Pulp bassist Steve Mackey. Justine Frischmann also has a writing credit on "Galang," which means that fully half of the people who worked on the song came from gigantically popular '90s Britpop bands. It sure doesn't sound like Britpop, though.

A tiny indie label called Showbiz Records pressed up a few hundred vinyl copies of the "Galang" single in 2003, and those copies found their way to the people that the song needed to find. Even before M.I.A. signed with XL Recordings, the "Galang" single had critical buzz among the kinds of MP3 bloggers who were discovering leftfield art-pop artists like Annie and the Knife around the same time. "Galang" fit into that post-electroclash wave, but it also seemed more directly connected to rap and grime and dancehall, which made it cooler. In 2004, M.I.A. joined Peaches and Electric Six and Badly Drawn Boy on the XL roster, and she put out a more widely-distributed version of "Galang." The single scraped the bottom of the UK charts, but it wasn't supposed to be an actual pop hit. It was a calling card, a statement of purpose. There was more where that came from.

M.I.A. recorded her second single "Sunshowers" with the Cavemen, and she built it on a sample of disco exoticists Dr. Buzzard's Original Savannah Band. Over that track, M.I.A. describes some version of everyday life in a place like Sri Lanka -- the guy who wears Reebok classics to his job in the Nike sweatshop, the snipers that might splatter your brains on the wall if you lose focus. The sloganeering really starts here: "Like PLO, I don't surrendo." In the video, M.I.A. climbs trees and rides elephants. When she says that she salts and peppers her mangos, that's a statement of pride from a South Asian culture that wasn't often depicted in mainstream media -- one that's still not often depicted in mainstream media. Seen from a certain angle, it might also be an invitation to cultural tourism. Once again, though: A banger.

M.I.A kept making tracks with the assistance of some of the coolest producers on the early-'00s landscape. She co-produced her third single "Hombre" with Richard X, the former mash-up specialist whose Adina Howard/Tubeway Army fusion "Freak Like Me" became a classic UK chart-topper for the Sugababes. M.I.A. made the baile funk pastiche "Bucky Done Gun" with Diplo, the American DJ who would play a huge part in her story. I knew about Diplo before I knew about M.I.A., and that's a proximity thing. I was in Baltimore, and Diplo was one half of Hollertronix, the Philly DJ duo who threw legendary parties by building dizzy sets out of Southern rap, dancehall, Baltimore club, and the occasional alt-rock or mainstream sugar-pop banger. A friend passed me a CD-R copy of Never Scared, Hollertronix's 2003 DJ mix, and it became a huge thing for me -- all the music that I wanted to hear in one place, blurred together with ADHD immediacy through connections that might've never occurred to me if Diplo and Lowbudget hadn't pointed them out.

Diplo was especially into Baltimore club and Brazilian baile funk, a genre that's in the middle of one of its periodic viral moments right now. He loved the way that baile funk, much like Baltimore club, went sample-crazy in its pursuit of ultra-physical party-music nirvana. He curated the kind of baile funk compilation that you could buy at Other Music, and he painted a lurid picture of the favela scene for The FADER. His "Bucky Done Gun" beat takes its chopped-up Rocky-theme horns from Deize Tigrona's 2004 baile funk track "Injeção." M.I.A. later talked about how weird it was when Brazilian radio, which always ignored actual baile funk, started playing "Bucky Done Gun." Some of her "Bucky Done Gun" lyrics are pure nonsense: "I'll hard drive your bit/ I'm battered by your sumo grip." But her sloganeering is sharp -- "London, quieten down, I need to make a sound!" -- and the contrast between the frantic music and the blasê delivery hits even harder.

Diplo didn't really produce that many tracks on Arular, but he became an important part of M.I.A.'s story anyway -- to her regret, possibly. Diplo and M.I.A. became an item. Later on, she talked about how he constantly made her question herself, telling her that it was wack to sign with a big label or do magazine interviews, and that she later realized that he was just jealous. (Diplo wasn't publicity-shy back then, and he damn sure isn't now.) At the time, though, they seemed like the world's coolest power couple, the people who knew how to navigate the chaotic global beat-music landscape. Diplo needed M.I.A.; he never would've been a celebrity without her. His first attempt at a commercially available album was 2004's Florida, a pretty-decent piece of DJ Shadow-esque downtempo chill music that had none of the energy of his DJ mixes. M.I.A. brought that out.

In 2004, M.I.A. appeared on the cover of The FADER with no album out, which was pretty much the pinnacle of press hype in those days. I really wanted to drive up to Philly to see her perform at a Hollertronix party with Bun B, but I got sick or it snowed or something. She was supposed to have her album out by the end of that year, but she and Diplo did something else instead. They made Piracy Funds Terrorism, Vol. 1, a mixtape that blended the tracks from her then-unreleased record with tons of recognizable tracks from Clipse, the Go-Go's, Ciara, Kraftwerk, Dead Prez, Madonna. It wasn't really an album, but it was one of my favorite albums of 2004 anyway. I was especially amped to hear M.I.A. chanting over KW Griff's "You Big Dummy," an anthemic Baltimore club instrumental built out of Quincy Jones' Sanford And Son theme. Some of my favorite memories were driving around with my friends, blasting 92Q late at night, and absolutely going off when K-Swift would play "You Big Dummy." "You Big Dummy," and Baltimore club in general, felt like an extremely cool local secret, a thing that the rest of the world didn't know about. But M.I.A. heard "You Big Dummy," and she understood its power. I loved her for that.

Maybe it was just supposed to be a mixtape track at the time, but that "You Big Dummy" sample turned into "URAQT," the text-speak sex song that probably still stands as my favorite track from Arular. (The song wasn't on every edition of the album at first because the Quincy Jones sample-clearance process complicated things.) "URAQT" had competition. Pretty much every track on Arular is a banger. A handful of producers might've worked on Arular, but every song still had the homemade intensity of M.I.A.'s original demo. There isn't too much aesthetic variance on the album, even if the beats contain echoes of so many different sounds. Instead, the music is mean and propulsive and minimal, and M.I.A. lets her voice dance over it. Her lyrics have a way of working as hooks precisely because they work as quasi-political slogans: "Pull up the people, pull up the poor," "I got the bombs to make you blow," "Daddy's MIA, missing in action/ Gone to start a revolution."

M.I.A. has said that Arular is named for her father's code name and that she used the title even after her father, who she hadn't heard from in years, asked her not to call it that. When the record came out, plenty of critics tried to figure out where, exactly, the record sat politically. Was M.I.A. just a privileged British kid who played around with guerilla-warfare symbolism for transgressive thrills? Or was she sincerely advocating a political position that much of her audience didn't understand? Both sides had plenty of evidence to support their claims, but the album wasn't that deep for most of us. Instead, Arular resonated because it worked as transcendent party music. Arular wasn't a commercial smash on either side of the Atlantic, but in hipster dance-party circles, "Galang" hit just as hard as "Work It" or "Technologic" or "You Big Dummy."

M.I.A. made for fantastic magazine copy. She was gorgeous, which mattered. She also offered writers an opportunity to discuss exciting musical developments and real-world politics -- subjects way richer than anything you could find on, like, a Decemberists record. (The Decemberists' Picaresque came out the same day as Arular and sold way more first-week copies in the US, and I took that as a sign that indie rock fans were sliding toward irredeemable dorkitude.) Critics went crazy for Arular and treated M.I.A. with way more seriousness than any of that moment's actual pop stars -- save for one. I speak, of course, of M.I.A.'s fellow middle-aged reactionary crank Kanye West, who loved M.I.A. as much as every other hipster. On that year's Pazz & Jop critics' poll, Arular came in at #2, behind only Late Registration. The year's #3 finisher was Illinois, and maybe we should offer Sufjan Stevens more praise for not becoming a middle-aged reactionary crank. He beat the odds!

M.I.A. went out on tour with fellow cool-kid critical fave LCD Soundsystem, and then she hit arenas asthe opening act for Gwen Stefani, speaking of middle-aged reactionary cranks. If you could time-travel back to one of those Stefani shows, you could get material for 15 different term papers about pop symbolism and cultural appropriation. Still, whether or not M.I.A.'s revolutionary signifiers were pure poserism, they still had an effect on her life. When it came time to record her second album, M.I.A.'s American visa was denied. She rented a New York apartment, but she didn't have access to it for a long time. When the Village Voice, my employer at the time, booked M.I.A. to play its Siren Festival in 2007, nobody was sure whether she'd be able to get into the country until a few days before the show.

The conversations about M.I.A. continued to reverberate for almost as long as the music on Arular. It's never a great idea to psychoanalyze a chaotic-ass musician, but my theory on M.I.A.'s downfall is that she started believing her own hype. You almost can't blame her. Arular lived up to all that hype in 2005, and it still sounds amazing today. Too bad about the person who made it.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!