- Merge

- 2005

There he was: Britt Daniel, carrying his camera around Times Square. It was the fall of 2003, maybe 2004. I was a scrubby Midwestern undergrad visiting New York City for the CMJ Music Marathon, a sort of "SXSW in NYC" situation where buzz bands played umpteen times in venues around town. Spoon were not on the lineup, and setlist.fm does not indicate they had a show in the area at those times. He seemed a bit surprised when I recognized him and said hi. I was surprised to spot him there, too. It was not unthinkable to run into a rock star in Times Square during the TRL era, but Spoon were the province of MTV2, having scored a low-key hit with "The Way We Get By." He was too cool to be there, but he was right in front me, stalking the city's gaudiest tourist trap, snapping photos.

Flash forward to the spring of 2005. Spoon's full new album had already leaked — such was often the case back then — but the official rollout was just beginning. When the lead single dropped at the end of March, it was a funky, stylishly minimal track called "I Turn My Camera On." Although the Leonardo DiCaprio pointing meme from Once Upon A Time In Hollywood would not exist for another decade and a half, in that moment I was its human embodiment. He really does turn his camera on, I thought. The man did not lie.

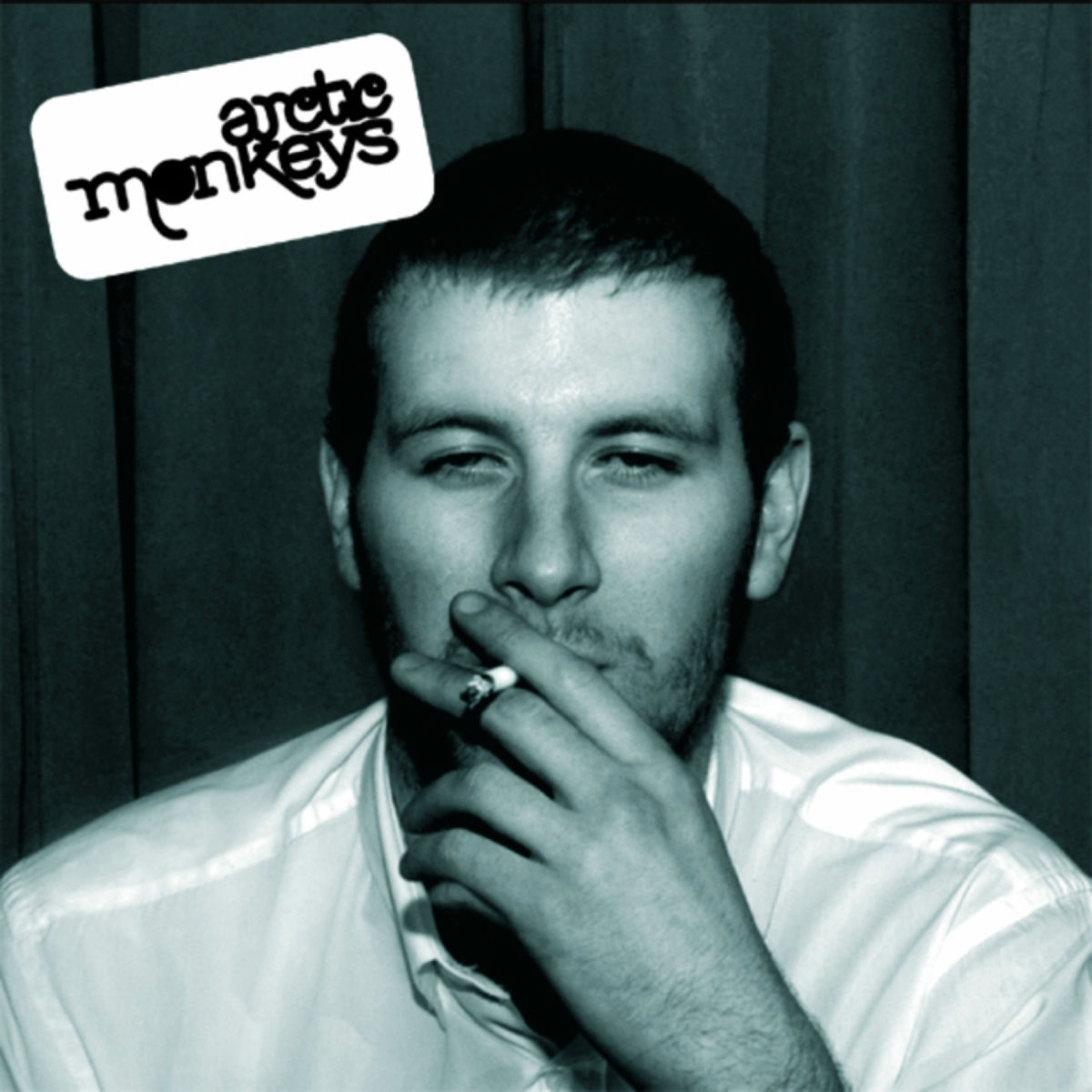

"I Turn My Camera On" was the closest Spoon came to riding the zeitgeist. By 2005, indie rock's dance-punk era had crossed over to the mainstream thanks to the likes of Franz Ferdinand (described by Kanye West as "white crunk") and the Killers, whose glamorous, ostentatious "Mr. Brightside" was on its way to the top 10. The peak DFA moment had passed, but LCD Soundsystem were just getting started. A song that seemed self-consciously designed for indie dance nights could be received as a bit opportunistic — and indeed, Daniel was consciously channeling "Take Me Out," having learned that his ex-girlfriend, Eleanor Friedberger of the Fiery Furnaces, was now dating Franz frontman Alex Kapranos. "I'm not sure if it was the fact that she was going out with him, but for some reason I felt really compelled to write a song sort of around that same groove," he later told EW. But like the Stones dipping into disco on "Miss You," "I Turn My Camera On" never feels like a reach. It may be commercial-ready, but it's also an extension of Spoon's unmistakable essence.

Gimme Fiction, which turns 20 this Saturday, is like that all the way through. It's the Spoon-iest of Spoon albums, the one without an angle or gimmick beyond one of the best damn rock bands kicking out heat. Spoon's '90s output leaned into their post-punk influence; 2001's Girls Can Tell embraced soul and vintage pop songcraft; 2002's swaggering, experimental Kill The Moonlight (my personal favorite) stripped the band's sound to its studs and let noise haunt the empty spaces. Gimme Fiction was the sound of it all coming together. Spoon were not necessarily leveling up — more like leveling out into an accessible but eccentric signature sound that would follow them for the rest of their career. It's fair to think of Gimme Fiction as a ramp-up to 2007's universally adored Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga, but without that comparison point we might say they'd already perfected that ideal here.

For years, the beaten-to-death critical narrative has been that Spoon don't have a narrative, and Gimme Fiction certainly doesn't. But you don't need a compelling backstory or controlling idea when the songs are this good. The album is meticulously constructed yet hits hard: an expert triangulation of power and finesse, of sophistication and raw instinct. Daniel, drummer Jim Eno, and producer Mike McCarthy carefully pieced together each song; soon-to-depart bassist Joshua Zarbo and incoming multi-instrumentalist Eric Harvey tap in only on the thundering religious critique "My Mathematical Mind," a song that reacts against "I Turn My Camera On" by pushing all the way into brass-blasted maximalism. Yet despite the clinical crispness of it all, the record breathes with the same urgent vigor Spoon bring to the stage. It's virile, not sterile.

That virility arrives in full force on opener "The Beast And Dragon, Adored," an apocalyptic stomper that conflates the Second Coming with an artist's return from a creative retreat, freshly inspired and empowered. In Daniel's case, the retreat was to the beaches of Galveston, where he stowed away to successfully fend off a fit of writer's block. "When you don't feel it, it shows/ They tear out your soul," he sings. "And when you believe, they call it rock and roll." He brings that kind of conviction to the track, channeling Lennon and Bowie's soulful combustion over ominous, resounding piano and the kind of volatile guitar spasms you'd expect to hear from Pavement or Pixies — classic rock and indie rock finding sweet synchronicity. To wit, more than anything, it reminds me of Jeff Tweedy's unhinged playing on the prior year's A Ghost Is Born.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

The character sketch "The Two Sides Of Monsieur Valentine," on the other hand, is all smooth propulsion, its orchestral strings swirling surreally over the groove a la "Glass Onion." (For a band that has become indie rock's own Rolling Stones, Spoon sure do have a lot of Beatles in them.) They keep hopscotching across styles from there: hard-charging jangle rock on "Sister Jack"; a slinky, sound-designed groove on "Was It You?"; a strummy acoustic shuffle on "I Summon You"; an anxious krautrock boogie on "They Never Got You." That piano comes pounding into so many songs, contributing to the old-school rock ‘n' roll sensibility that has always set Spoon apart from their indie contemporaries. Yet just as often the band takes on a lithe, futuristic feel, kicking out arty dance-rock that betrays Daniel's Prince fascination, laying the groundwork for future sonic adventures. An unrelenting personality courses through it all, a unifying palette and point of view, but upon revisitation it's remarkable what a vast universe they constructed here.

Much of that coherence has to do with Daniel's presence at the center of it all. As always, he's evocative but elusive, poised yet gritty, singing with the biting sweetness of a Jack and Coke, like Elvis Costello without the nerd glasses. His lyrics never quite let you in, but they give you glimpses of interpersonal dynamics, poetic scene-setting to be puzzled out and refracted into your own experience. The memoir-ish "Sister Jack" bucks that trend; as someone whose early adolescence was forged in the fires of Sam Ash and guitar magazines, I've always smiled knowingly at the line "I was in this drop-D metal band we called Requiem." But even at his most relatable, he's a cipher, keeping enough emotional distance to remain a rock star rather than soul-baring troubadour.

In that sense, it's perfectly in character that he was mysteriously making his way around Times Square that day all those years ago. In that moment he was living out the ethos of "I Turn My Camera On," a song about how disappearing behind a lens can create a buffer between you and the world, about how getting burned by evasive characters can teach you to toggle your feelings on and off, about letting people get this close without ever quite getting a grip on you. "I don't think I'm untouchable," he later told NPR. "But sometimes I've felt that way." If I'd just made an album as good as Gimme Fiction, I might feel untouchable sometimes too.