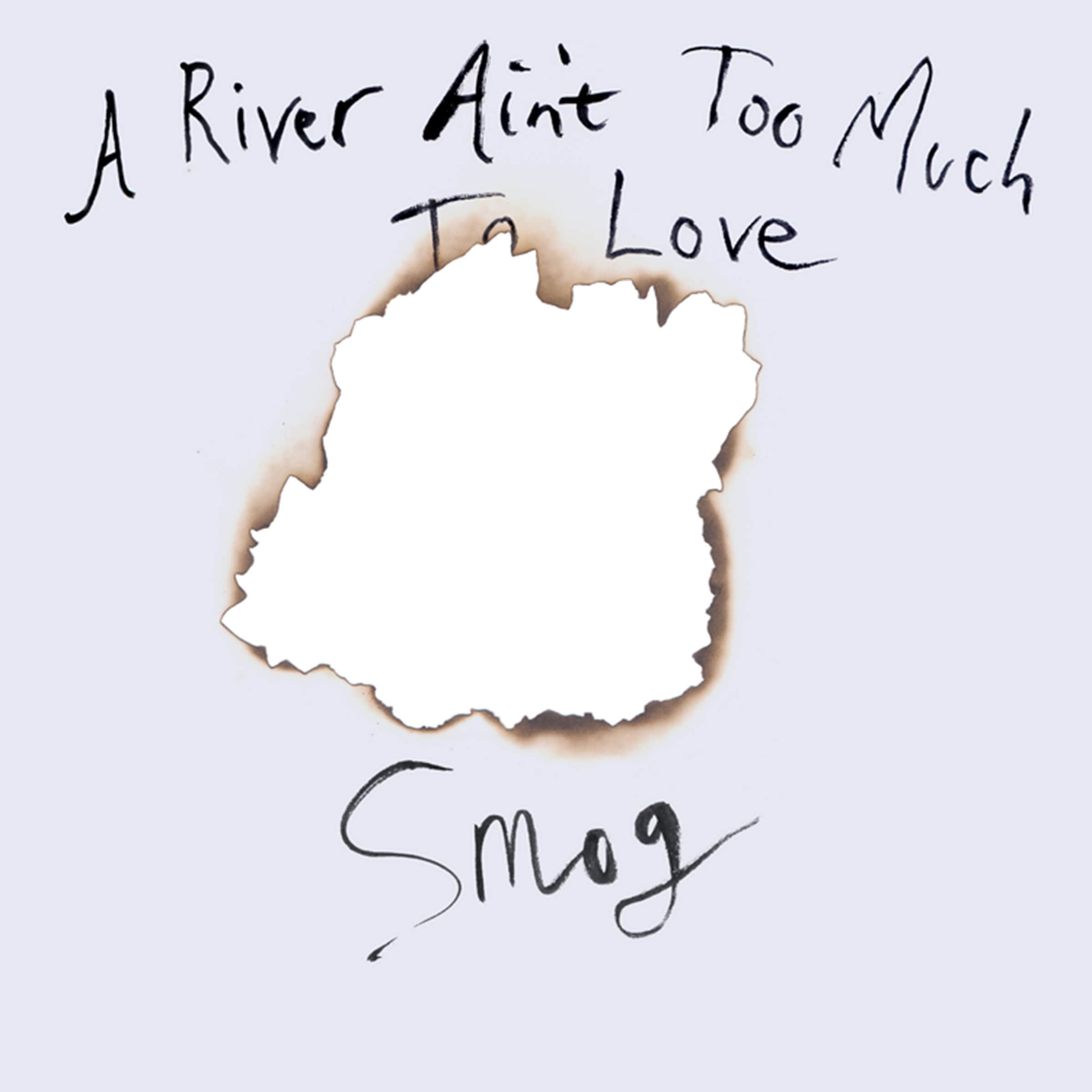

- Drag City/Domino

- 2005

Country music loves horses. Not as an animal, but as metaphor. How many country stars actually rode a horse outside of a photoshoot? Porter Wagoner certainly couldn’t in his Nudie Suits. But the idea of a horse — an animal that symbolized the American west, Native American culture, and, above all, freedom — could be slapped onto any song.

Something tells me Bill Callahan knows his horses. Both due to the terminology he’s used (colts, fillies, and foals, galloping and cantering) and the way he’s woven them into the wide, sprawling tapestry of the Callahan extended universe. From the lonely colt on the sun dappled cover of Sometimes I Wish We Were An Eagle to his absurdly bleak view on human connection on "I Break Horses," there’s inevitably some caballo trotting around in the background of his songs. On A River Ain’t Too Much To Love, released 20 years ago this past weekend, Callahan asked, "Is there anything as still as sleeping horses?"

This was his last album under the Smog moniker and, though no one knew it at the time, it marked a subtle but important transformation. The stakes were lower than on the ennui-distilling questions of later albums Apocalypse or Dream River. And though A River Ain’t Too Much To Love was concerned with the physical, it didn’t lurch into the reckless, horndog fever that Knock Knock extolled. As Smog, and as a part of the wider alt-country scene, his closest contemporary was Bonnie "Prince" Billy. They were both jackasses who were too smart for their own good, meeting every emotion with a smirk. Will Oldham claimed the inevitability of death made "hosing much more fun" and Callahan similarly matched outsized emotion with absurdity. He called his backup singers "the Dongettes" on the exhilarating "Bloodflow," and paired the bone-shattering trauma of "Cold Blooded Old Times" with his catchiest hook. That never undercut the power of those moments, but as he grew older, he had less of an inclination toward irony, instead living in contradictions rather than pointing them out. He sang constantly about change on A River Ain’t Too Much To Love, but always pointed out that he was still the same person, his mutability inherent. "I did not become someone different/ I did not want to be," he sang before negging a woman while sipping a Lone Star. "She said I had an ego on me/ The size of Texas/ Well I'm new here and I forget/ Does that mean big or small?"

Part of that evolution was geographical. It was around this time that he found himself in Austin for SXSW and decided to stay in Texas for the rest of his life. In a Texas Monthly interview he revealed, "Someone invited me to a party afterward — no one had invited me to a party in Chicago, like, ever. It felt like people here were happy." The iconography of cowboys and horses were always hints of a southwestern soul trapped in northern climates. He confirmed as much on opener "Palimpsest," on which a distant harmonica rolled and wailed like a train on the horizon. "There’s something fundamentally wrong/ Like I'm a southern bird/ That stayed north too long," Callahan sang, as scared and weary as he’d ever sounded. His early recordings suggested constant, vagabonding motion. "Hit The Ground Running," "Let’s Move To The Country," and "Teenage Spaceship" all contained the young man truism that life could be grand if I could just get the hell out of here. But A River Ain’t Too Much To Love was his first album to suggest running to something was just as important. The album was recorded near one of Texas’ best state parks (Pedernales) and, if you’ve ever been out there, it’s easy to listen to Callahan’s references to moving water as a tribute to the waterfalls and green rivers cutting through the limestone hills. Callahan also shouted "fuck all y’all," on "The Well," which is as Texan as it gets.

Callahan’s singer/songwriter contemporary Jens Lekman once proposed that songs should be "emotionally autobiographical." Details must replicate the original feeling of a time, a relationship, a state perfectly, but maybe not the exact circumstances. The few pointed moments Callahan dredged up from his life acted as anchoring points, centering the songs’ emotional power. "Skin mags in the brambles/ For the first part of my life, I thought that women had orange skin," he muttered on the woozy "Drinking At The Dam." "Jarheads" and "warm beer" filtered through a nostalgic revery that celebrated a less heralded part of innocence: being a shithead and not knowing shit. And only Callahan could make it sound like a hymn.

Eventual ex Joanna Newsom showed up on "Rock Bottom Riser," adding piano on an ode to Callahan’s family, and a realization that he wasn’t ready to be tied down. "I saw a gold ring at the bottom of the river/ Glinting at my foolish heart/ Oh my foolish heart had to go diving/ Diving, diving, diving into the murk," he admitted, losing track of the sun as he started to drown. Great song to invite your girlfriend to play on, Bill. A year later, he added his booming baritone to Newsom’s own breakup epic "Only Skin" as their relationship dissolved. "Only Skin" was a 16-minute-long suite that compared heartbreak to beached whales, going blind, and an entire world collapsing. The closest Callahan got to that sort of cosmic grandeur was on the raucous, chiming "The Mother Of The World," which kicked off with one of his finest koans: "Whether or not there is any type of god, you’re not supposed to say/ And today I don’t really care/ God is a word, and the argument ends there." Callahan left the door just ajar for spirituality, a winking Pascal’s wager as he returned his focus to the physical reality of everything he could touch, and break.

The focus on physicality was backed up by the small cohort of musicians Callahan invited into his world. There was deft but never delicate drumming from Jim White (the answer to the question "why does this random indie rock album have such kickass drums?"). Austin staple Thor Harris added a strange collection of percussion instruments for texture. And Connie Lovatt of defunct indie rockers the Pacific Ocean granted a subtle touch of bass and vocals to Callahan’s ramblings.

We rely on reader subscriptions to deliver articles like the one you're reading. Become a member and help support independent media!

Callahan was nearing 40 when A River Ain’t Too Much To Love came out, and welcoming folks into his world was a mark of maturity.A younger Callahan thrashed against inevitability. But as he retired Smog, he saw acceptance as a beautifully morbid thing. "With the grace of a corpse in a riptide, I let go," he sang on the stunning "Say Valley Maker."

The wailing, wayward harmonica that opened the album reappeared on closer "Let Me See The Colts." The tone and the notes were similar, but completely recast in new context. It was the same, lonesome train chugging towards the horizon, but as A River Ain’t Too Much To Love came to a close, those forlorn wails suddenly suggested exploration. That train was going somewhere, somewhere to disappear to. He was recasting the worry of "Palimpsest," which refers to a work of art where bits of the original draft or scraps of unused ideas are still tangible. It might’ve been a metaphor for Callahan’s whole career, slowly fading, but not erasing, vestigial bits of himself. In that aforementioned Texas Monthly article, longtime collaborator Brian Beattie claimed, "Bill is in that lifelong mission of becoming more and more like himself."

"Let Me See The Colts" fully embraced Smog’s old rough and rowdy ways just before casting them aside. Over a loping, rubber band guitar riff, Callahan roused some poor fella from bed in the wee hours of the morning to go hang out with horses. His worried buddy asking, "Have you been drinking?" only for Callahan to respond in a fever "No, nor sleeping/ The all-seeing all-knowing eye is dog tired." When I first heard the chorus, I thought Callahan’s intention to show the colts to a "gambling man" was a scheme to sell the animals to some mint julep drinking, Kentucky Derby obsessed suit. But further listening hinted that Callahan was talking about himself. It wasn’t Smog but, for the first time, Bill, leaning over the paddock fence, seeing the colts for all they were: the freedom, the future, and the boundless potential they held.