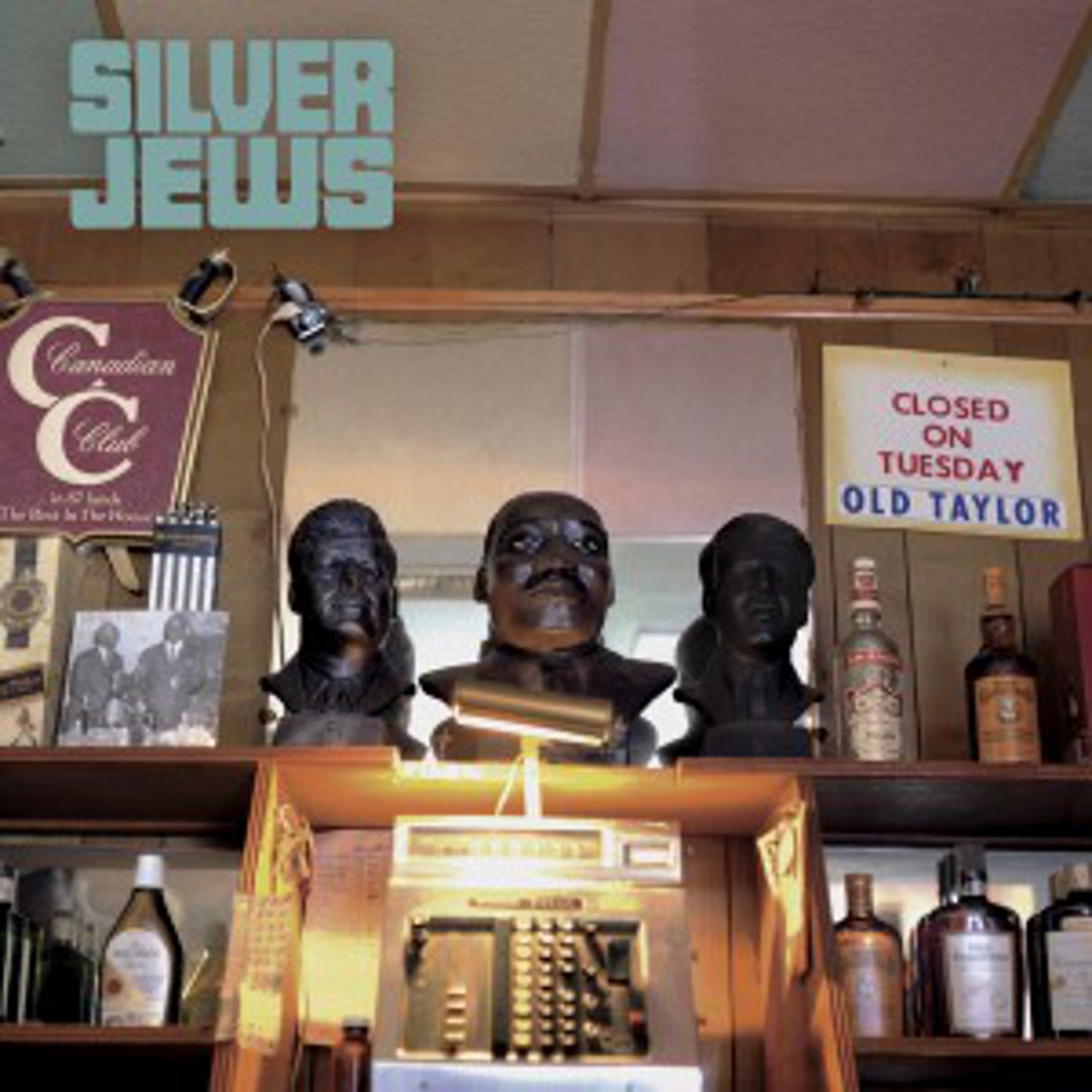

- Drag City

- 2005

David Berman died on my birthday. I found out about Berman's passing in the early evening, while I was out for ice cream with my wife and kids in the suburbs of Columbus, OH. When we got home, I grabbed my laptop and threw together whatever reverent, sentimental, hopefully accurate and insightful words I could for Stereogum's obituary. Like so many, I was gobsmacked.

At the time of his suicide, 52-year-old Berman had recently returned to the public eye after a decade away with first album from his new band, Purple Mountains. I'd always enjoyed Silver Jews, the band that made the poet and singer-songwriter a cult hero in the 1990s and 2000s, but to me, Purple Mountains was an obvious masterpiece and obviously the best thing he'd ever released. His writing at the end of his life was so raw, so wise, so searching, so tender, so pleasingly twisted in unmistakably Berman ways. I forged a close bond with those songs; they sent my heart and mind through the wringer, left me feeling hollowed out and filled with amazement.

The plan was to see Purple Mountains in concert about a month later when their inaugural tour rolled through Hopscotch Music Festival. I'd been feverishly anticipating that show. As I parasocially mourned Berman, I was also mourning the chance to sing "All My Happiness Is Gone" with a triumphantly raised fist on the streets of Raleigh. It would have been amazing. It would have been a mulligan for the one time I did see Berman perform, when I was too young and stupid to savor it.

In 2008, though not yet vibrating at Berman's frequency, I was at least savvy enough to perceive that a Silver Jews concert was a big deal. The band had been a touring operation for three years and two album cycles, but there was still a novelty to the idea that the formerly reclusive Berman was out there on the road, playing his songs in public. So I set up an email interview with Berman for the weekly newspaper that employed me at the time, and on the appointed date I headed to the peculiar gymnasium venue where Silver Jews had been booked. I did not arrive with the kind of reverent enthusiasm I would have brought to the Purple Mountains tour. Only in hindsight — maybe around the time Berman ended the band in 2009, definitely by the time he ended his life in 2019 — did I appreciate what a privilege it had been to encounter this guy doing his thing up close. I was bearing witness to a charmed, fleeting moment.

That brief mid-aughts stretch marks the only phase of Berman's life when he was regularly performing his songs in concert — a phase that began with Tanglewood Numbers. Released 20 years ago this Saturday, the album demarcated a distinct era in Berman's story, one where he was relatively happy, healthy, and actively trying to make life easier for his loved ones and business associates. The backstory is legend by now: In the years after 2001's Bright Flight, he'd survived a suicide attempt in his wedding suit, gone to rehab, rededicated himself to Judaism. As detailed in a wonderful Fader profile from back then, he invested himself in "increasing the general happiness," which involved things like giving doing press, going on tour, and taking care of himself.

Most days, I think Tanglewood Numbers is the best Silver Jews album. It doesn't have "Random Rules," the wry indie slow jam with an opening line so iconic it has become a meme on social media, but it does have a rejuvenated Berman singing some of his finest songs, backed by skilled collaborators that made those songs come alive in ways previously unheard of on a Silver Jews album. This was not a humble, shambolic indie band that existed mostly as a delivery system for Berman's lyrics; it was a crack country-rock unit, brimming with life and color, giving his sidelong wisdom the larger-than-life scope it deserved.

The supporting cast is wild: old pals Stephen Malkmus and Bob Nastanovich, but also William Tyler, Duane Denison, Paz Lenchantin, Will Oldham, Bobby Bare Jr., Azita Youssefi, and more. Together, they painted the corners of each track with elegant fiddle, spindly banjo, and all manner of tasteful guitar heroism, the rhythm section giving even the downtrodden songs a lively heave-ho. The hard-swinging clamor of "Sometimes A Pony Gets Depressed" — had a Silver Jews song ever moved like that before? "The Farmer's Hotel" — have you ever heard Berman backed by such a gorgeous arrangement? "Animal Shapes" — did this band ever release a better song for rumbling down the highway, windows down, pondering the clouds?

Most importantly, Berman's monotone drawl was often entangled with the songbird sounds of his wife, Cassie, who'd found his suicide note and rescued him from his self-inflicted overdose. On an album filled with beauty, her vocals may be the most achingly pretty sound. Throughout Tanglewood Numbers (named for the street they lived on at the time), Cassie's sweetness was an ideal complement to David's barbed sourness. Hearing them in call-and-response mode on "How Can I Love You If You Don't Lie Down" or harmonizing on "The Poor, The Fair, And The Good" is both heartwarming and heartbreaking, knowing it all went awry.

Owing to Berman's adoration for Cassie, there are a lot of love songs on Tanglewood Numbers. Some are gentle, like "I'm Getting Back Into Getting Back Into You" and "Sleeping Is The Only Love." But the best one truly rocks. "Punks In The Beerlight" opens the album with guitars that pierce the silence and a backbeat that sweeps you away. With its nods to the chemical and the metaphysical ("Ain't you heard the news? Adam and Eve were Jews"), it works as a sort of ultimate Silver Jews track, a state of David Berman address. "If it gets really, really bad," Cassie intones on the bridge, to which David answers, "Let's not kid ourselves/ It gets really, really bad." Yet the song is triumphant in its epic sweep, building to a brilliantly simple refrain: "I love you to the max!"

I think as a 22-year-old college senior, I found Berman's approach amusing. "I love you to the max" — haha, that's so blunt. "I've been living in a K-hole ever since you went away" — lol, wut! I was not attuned to Berman's gruff, indelicate tone. My sheltered ass could not relate to the hard living he was singing about. I was a Pavement kid who wanted Malkmus cameos on Silver Jews records, a Pitchfork-brained normie who would soon be getting my kicks from sparkling product like Surfer Blood and Passion Pit. I truly believe I was not mature enough to engage with Berman's work at the time. Not that I'm the picture of sophistication at this late date, but after having my mind blown by Purple Mountains, it's been so lovely to age into a deeper connection with Silver Jews, to return to songs that once bounced off me and discover the rough-and-tumble genius so many had been hearing all along. With each passing birthday, I'm more grateful for the body of work he left behind.