You belong among the wildflowers

You belong in a boat out at sea

Sail away, kill off the hours

You belong somewhere you feel free

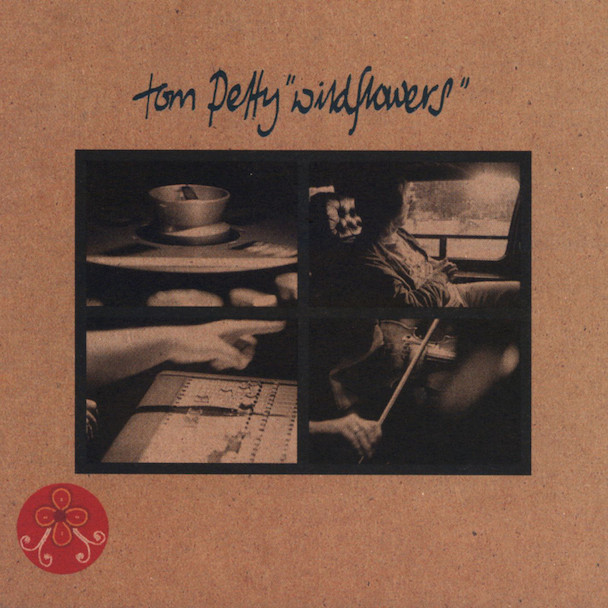

The opening verse of the title track from Tom Petty's 1994 mid-career high-water mark Wildflowers at first blush seems like little more than tattoo bait for young patchouli-spritzed women possessed of a penchant for calligraphy and easy-does-it-empowerment slogans. Listeners who dig deeper into both its songs and churning, drama-filled backstory, however, will quickly realize that, despite the second-person singular, this deliciously eclectic, sprawling fifteen-song rock 'n' roll epic is the sort of deeply personal, fully actualized declaration of independence one rarely sees from any artist -- think Dylan going electric at the Newport '65 stuffed into a supercollider with Nebraska-era Springsteen, the National Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Byrds.

"It's good to be king," Petty croons, but he steeps the words in enough world-weary melancholia that by the time he gets around to the "at least for awhile" it's crystal clear he's willing to abdicate the throne, relinquish his hard-won security, and undertake an uncertain attempt to conquer other aural territories.

And conquer he did, in probably the most subversive possible way amidst that moment's angsty, aggro cultural milieu.

Which is to say, Petty had the sort of earthy seventies hard rock cachet the brightest flaring lights amongst the Seattle grunge supernova were then so desperately attempting to appropriate. He certainly could've pulled off a better approximation of that sound than, say, Def Leppard did on Slang.

Hell, sharpen the teeth of "You Wreck Me" a bit and you're basically there. Lather, rinse, repeat.

Who would have blamed him if he had tread down that path? It's not as if Dave Grohl looked all that out of place when he sat in with the Heartbreakers for "You Don't Know How It Feels" and "Honey Bee" on Saturday Night Live in late 1994 -- the ex-Nirvana drummer actually turned down an offer to join permanently in order to focus on his fledgling then-one-man project, Foo Fighters -- and that sort of mutually beneficial, multi-generational back-scratching arrangement was definitely going around. Indeed, a few months after Wildflowers hit shelves, Neil Young would head to Seattle to make the Brendan O'Brien-produced Mirrorball with Pearl Jam, a collaboration that said a whole fuck of a lot more about the future trajectory of Cameron Crowe's favorite band than Vedder's turn as a backing vocalist on Bad Religion's "American Jesus" a couple years earlier. Nine Inch Nails took Bowie out. George Clinton ended up on Lollapalooza. Shit happened.

Maybe somewhere in the ether there is an alternate universe in which a slightly less principled Petty plugs into a Big Muff, adds some feedback squalls to his trademark jangle, and does interviews with Spin and CMJ bragging about how members of the Sex Pistols attended early Heartbreaker shows in England, where Petty & Co. achieved some degree of notoriety/popularity before the States took notice -- another factoid the no-one-gets-us flannel-flyers no doubt would've seen as a point in Petty's favor. Or the gigs played with the Ramones, Patti Smith, the Kinks, Blondie, the Replacements, etc. Or how, he learned hard way that his crowd could easily double as the Facebreakers when a San Fran audience at Winterland Ballroom dragged him off stage: "I've seen these bands that dive onto the people and get passed around," Petty tells Paul Zollo in the superb, edifying collection Conversations With Tom Petty. "Well, my crowd just tears you to bits."

Take that, sissies of the 1992 "Even Flow" video shoot!

So ... why? Why did Petty zig when it would have been so much easier to zag? Maybe for the same reason he recently laid out for the Los Angeles Times when the topic of why the Heartbreakers didn't glom onto the late seventies punk movement came up: "I didn't want to put on the outfit," he said. "I really felt an allegiance to their trip, and I loved the spirit of it, but our identity was too well formed to go that way. I remember one of them saying, 'You guys need to cut your hair.' And I was like, 'Mm, no.' Then I would be joining a club. I just want to be our own thing."

Wildflowers serves as the glorious apotheosis of Tom Petty being his own thing.

***

Wildflowers is Tom Petty's second solo record, but his first intentional one -- its multiplatinum predecessor, Full Moon Fever, was a lark that spiraled into an album: The Heartbreakers were taking a breather, scattered to the four winds as the tale is told, and Petty's future Traveling Willburys bandmate Jeff Lynne swung by the house for a casual jam session, and -- poof! -- the first thing that pops out is the chord progression and some ad-libbed lyrics which the world would soon have branded into its collective consciousness as "Free Fallin'," perhaps the most iconic song in Petty's storied canon.

"It's become synonymous with me," the singer-songwriter muses to Zollo. "But it was really only thirty minutes of my life."

Lucky for Petty, then, that his pal Lynne, perhaps best known as the frontman and sole consistent member of Electric Light Orchestra, also just happened to be a budding super producer and the next day the pair recorded the track with an assist from Heartbreakers lead guitarist Mike Campbell. While mixing the song, Petty and Lynne wound up writing "I Won't Back Down" in the studio.

You see where this is going. Synchronicity and synergy fill the air, the ineffable, elusive muse at long last been seized by its tail, the gates of Valhalla swing open, and Petty and Lynne embark on a writing spree, often slaying a track a day.

They simply couldn't help themselves, your Honor. The urge to folk-rock was far too strong.

Trouble was, no one had bothered to tell the rest of the Heartbreakers -- and by the time Petty invited keyboardist Benmont Tench, bassist Howie Epstein, and drummer Stan Lynch in to do guest spots to "smooth the wound over," as he put it in his own telling words, the gang was already pissed. The change-up in all likelihood couldn't have been a complete shock -- Lynch might've off-handedly come up with the title of the band's 1987 album Let Me Up (I've Had Enough), but Petty certainly had no qualms about running with it -- yet tensions nevertheless escalated quickly and, according to Conversations, when Epstein arrived to sing some backups he straight up told Petty, "You don't really need me for this, do you? I don't like it."

Petty continues:

I said, "Well, if you don't like it, I don't need you."

And he said. "Okay, I'm gonna go," and he left.

Right then I went, "Well, this is going to be a solo Tom Petty record, because I like it. And I'm not going to go through this vibe, and there's really no room for them on this anyway."

Now, this interview was conducted somewhere in the range of ten years past the event with torrents of water under the bridge. The contemporary Petty, on the other hand, framed things in a more conciliatory manner: "I could have done this album with the band, but it was just circumstances that led to a solo album," he told the Los Angeles Daily News in 1989. "Once things were underway, I didn't want to stop for any reason. I had some momentum going, and I wanted to go with it."

If the Heartbreakers had taken that maybe-not-one-hundred-percent-forthcoming explanation in stride, there may not have been a Wildflowers. Petty may not have been tempted to attempt a breakout in the same way.

Of course, there were other factors as well.

As Petty entered his forties and middle-age he naturally began to revaluate his life and career, a heightened awareness that gained greater urgency courtesy two experiences in 1987: First, in May, a psychotic arsonist had set Petty's Encino home ablaze and the singer-songwriter, his wife, and daughter barely escaped with their lives. ("If you've ever had anybody try to kill you," he tells Zollo, "it really makes you reevaluate everything.") And then in October, while he and the Heartbreakers were in the midst of a four night stand backing Bob Dylan at Wembley Arena as part of the Temples in Flames tour, the violent extratropical cyclone known as the Great Storm of 1987 -- by many accounts the strongest storm to hit London in three hundred years -- brought a bit of the apocalypse to Petty's hotel doorstep. And Petty, big on symbolism ever since a chance meeting at eleven years-old with Elvis on the set of Follow the Dream launched him down a path of rock 'n' roll obsession and (eventual) stardom, took notice…

"I knew that hurricane meant my life was going to change."

The Heartbreakers could escape the storm, but not the desires engendered or questions raised.

Petty described the conundrum thusly to Zollo:

In those days, when we did [the early records], there weren't that many rock n' roll stars over thirty. You didn't think it was going to go on that long. My dream was that maybe I could learn to be a record producer…I never thought our trip was going to go on so long. I thought if it went on five years, in those days, that was really successful. We never thought about growing old doing it.

Petty insisted to anyone who would listen that he did not want to bust up the Heartbreakers. But it's fairly obvious after years of going full bore pushing the band he did want to expand his horizons a bit -- you know, that's the kind of bug you're bound to catch when Roy Orbison, Johnny Cash, and Bob Dylan start treating you like a peer, Gary Shandling invites you to act on his Showtime sitcom, and you become friendly enough with George Harrison that he randomly comes over your house to teach you how to play the fucking ukulele.

Or as Petty put it to Q Magazine while discussing a wall-punching incident during the recording of Southern Accents in which he pulverized his hand over his frustration at the track "Rebels" not coming quite together and, as a result, needed reconstructive surgery (!) and couldn't play guitar for eight months (!!) -- in a quote recently unearthed by journalist Jeff Giles for a wonderful Ultimate Classic Rock article on Full Moon Fever): "I realized I couldn't go on living so intense and revved up and stuff. Because, with some kind of flash of realization, I realized that I had actually never really enjoyed myself. I'd done partying and I'd done work, but I'd never genuinely enjoyed myself. I'd been very reclusive and I didn't know a lot of people and I didn't ever see many people. I wasn't very social at all, because I was revved up all the time. And I just was not very happy. It was time to calm down. And I made this great discovery: people are quite fun, you know."

Right. And sometimes in addition to being fun they help you create a colossally successful solo album or ask you to join a ridiculously stacked rock n' roll super group. So Petty did Full Moon Fever and the Traveling Wilburys record. The Heartbreakers toured Full Moon Fever and drummer Lynch bitched about feeling like he was in a cover band. Resentments simmered and Petty's return to the fold for Into the Great Wide Open [1991] sure sounds as if it was more out of obligation than anything else. "I had a responsibility to the Heartbreakers," Petty tells Zollo. "I'd been gone for a long time."

Though Into the Great Wide Open spawned a couple hit singles -- "Learning to Fly"; the title track -- and sold well, if a band truly is, as we hear ad nauseam, like a marriage…well, we all know how well things turn out when a couple stays together for the children.

The follow-up, Petty declared, would be another solo record. A still youngish, hungry thirty-one year-old Rick Rubin, not Jeff Lynne, would produce. Petty wanted the Heartbreakers to back him, but playing the reconciliation game hadn't delivered much in the way of dividends and he made no bones about the fact that he alone would be the headliner this time out. "Rick and I both wanted more freedom than to be strapped into five guys," he recalls in Conversations. "We wanted to be able to do whatever we wanted, really, as far as bringing in this guy or that guy."

It was a brutal power move to pull on bandmates he'd been playing with for nearly twenty years—more, for a couple of them, if you counted the Gainesville Heartbreakers forerunner Mudcrutch.

For Lynch this was the lit fuse finally reaching the bomb. He left the band.

Undeterred, Petty demo'd songs on an eight track at his house down to the minutest detail, letting Rubin pick over each one and make suggestions before bringing them into the studio for tracking. During the recording sessions, Rubin leaned on Petty hard, pushing for take after take after take. Conductor Michael Kamen, who had collaborated with a slew of superstars and was probably best known for his work on Pink Floyd's The Wall, came on to arrange and supervise the orchestral elements. Ringo Starr and Carl Wilson made guest appearances.

The process was arduous -- "[Wildflowers] sounds like it was made on a weekend," Rubin told Mix Magazine in 2000. "Of course, it took us two years to make it sound like it was made on a weekend ... the right weekend!" -- but by no means insular, even if Petty had voluntarily taken the weight of his vision almost entirely on his own shoulders. He defended the purity of the songs and experience zealously. When MCA came knocking looking for a new track to tack onto the Heartbreakers upcoming Greatest Hits collection, Petty refused to adapt one of the germinating solo Wildflowers songs for that purpose, choosing instead to resurrect a jam from the Full Moon Fever sessions, the unlikely hit "Last Dance With Mary Jane."

"My kids have this huge laugh about me," Petty tells Zollo. "I just spent some time with them, and they were laughing about my image. They said, 'The world pictures you as this laid-back, laconic kind of person, and actually you're the most intense, neurotic person we've ever met.' And that's kind of true. You're not always what people picture you as. Like 'laid-back.' I am not a laid-back person."

More than twenty songs were recorded. Originally planned as a double album, Petty recorded more than twenty songs. Many that didn't make the Wildflowers cut would eventually surface on the She's the One soundtrack, which Petty has called "almost Volume II of Wildflowers."

Ultimately, Petty was vindicated. He calls the Wildflowers sessions a moment when his "craft and inspiration colliding at the same moment," and it's tough to argue with results. This is a record that (mostly!) eschews immediacy, easy applause legacy riffage, and the straitjacket of cohesiveness in favor of nuance, subtlety, and sonic adventurousness. Lush and expansive, varied yet familiar, over its hour-plus run time the album creates its own ecosystem.