Who knew a tweet from Weezy last December would unfold into the ugly soap opera that is Lil Wayne vs. Birdman? After nine months, three lawsuits, three spinoff dramas, direct verbal shots, social media shots, subliminal lyrical shots, actual gunshots, a hurled drink, two mixtapes, and an album, here we are.

Even after all of that, though, there was perhaps more significant subtext hidden in Weezy's 94 characters. His tweet may signify the end of an era: the demise of the radio-ruling vanity rap dynasty. The Lil' Wayne-founded label YMCMB is the last of a dying breed. Artists are continually finding comfortable independent situations and are not concerned so much with radio airplay. There are so many sources and outlets for music that fans no longer have to look to major labels for what appeals to them. Ticket sales and other forms of revenue have displaced album sales as the main money maker. The interwebs have threatened to render distribution deals obsolete for quite some time now, and artists are becoming much less ignorant about the business of music with streaming services in the forefront of conversation. Rap's perfect storm of novelty, mystery, edge, and the masses that are more than ready to consume it, has passed. Assembling a "Dream Team" roster capable of taking over the radio and moving massive amounts of units is exceedingly difficult -- 2015 is definitely not 1992. YMCMB may have been the last to wield that power.

But before we say goodbye to those fading empires, let's take a stroll down Memory Lane and remember the vanity rap labels that had the airwaves, Walkmans, Discmans, car stereos, home systems, and iPods on lock in their prime. Please keep in mind that this is not a ranking pertaining to strength of the roster or quality of their music. That is an entirely different list. This is based on data from Billboard charts, plaque certifications, and the context in which those songs charted and listeners grabbed those units off the shelves. Those factors are not always indicators of the music being particularly good.

10. Shady Records

Dr. Dre's artistic family tree is ripe with American music royalty, and Eminem's branch has grown heavy enough to break off entirely. Em said he would kill for Dre on Chronic 2001, and more recently, on Compton, Em expressed his gratitude for Dre's crucial endorsement of his skills. Apparently, Dre schooled Em on the business of music and helped hone his eye for seeing viable talent in others, too.

Shady now boasts 19 diamond, platinum, and gold albums collectively. Obviously, seven of those belong to Eminem, and four of them belong to 50 Cent jointly with Aftermath Records. But the other eight albums alone cement a stronghold that belongs solely to Shady.

Eminem the visionary is nowhere near as formidable as Eminem the artist, but praise is due. He brought 50 Cent to Dre. He assembled one hell of a supergroup in Slaughterhouse. He extended the legitimacy he earned to childhood friends D12 and Obie Trice. And while Yelawolf is not the most important of rappers, the Alabama rep can hold his own on a roster of vicious venom slingers.

A legacy of his mentor's stature is most likely not imminent for Eminem as a labelhead and business man, but with his sense of talent and the next generation of rappers waiting in the (red) wings, he still might get there.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

09. Ruff Ryders

Truly, this is the house that Dark Man X built, but the Ruff Ryders had a solid squad of spitters in their heyday. Leaving aside DMX's five platinum #1 albums, the LOX had a platinum album on Ruff Ryders after being acquired from Bad Boy, Eve had two platinum efforts and a gold album, and the underrated Drag-On had a gold album. The clique's first compilation album, Ryde Or Die Vol. 1, hit #1 and went platinum as well. With a grand total of nine platinum albums, two gold albums, and 32 tracks on the Billboard Hot Hip-Hop/R&B charts, the Ruff Ryders did the damn thing.

More important than the impressive numbers is the time in which they put them up. The Ruff Ryders rose to popularity when hip-hop was migrating all over the country. West Coast G's had taken over in the early/mid '90s with N.W.A. and Death Row. The South was enjoying burgeoning prominence from the success of Outkast, Goodie Mob, the first wave of Cash Money, and Master P and his No Limit soldiers. While there were strong blips on the East Coast like Nas' Illmatic and the start of Jay Z's rise with Roc-A-Fella, there was an overwhelming feeling that the birthplace of hip-hop would simply be a historical landmark unfit for the commercial success for which rap was poised.

Ruff Ryders' brand of Tims-and-hoodies rap was distinctly, unapologetically East Coast, and the country loved it. Yonkers was represented with DMX and the LOX; Eve was holding it down for Illadelph; Drag-On and producer Swizz Beatz were representatives from the Bronx. Swizz's sound would permeate throughout New York's scene as well, also becoming a part of the signature Roc-A-Fella sound that would shape the East Coast radio aesthetic in the early 2000s. The accents were strong and unmistakable. The lyrics were raw, aggressive, and delivered through flows that were a refined ode to the East of old(er). Though they resembled a biker gang -- clad in their bandanas, branded leather jackets and vests with the signature R, Timberlands, and baseball bats -- they oozed East Coast hood.

The label, dba Ruff Ryders Entertainment, only just dissolved in 2010 after the more successful artists went on to acting, fashion, and art (among other things), founded their own labels, or just left the game; but the Ruff Ryders symbol still holds weight in the motorcycle community and is a source of nostalgia for East Coast fans, who followed Ruff Ryders into the commercial rap fold of the bling era.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

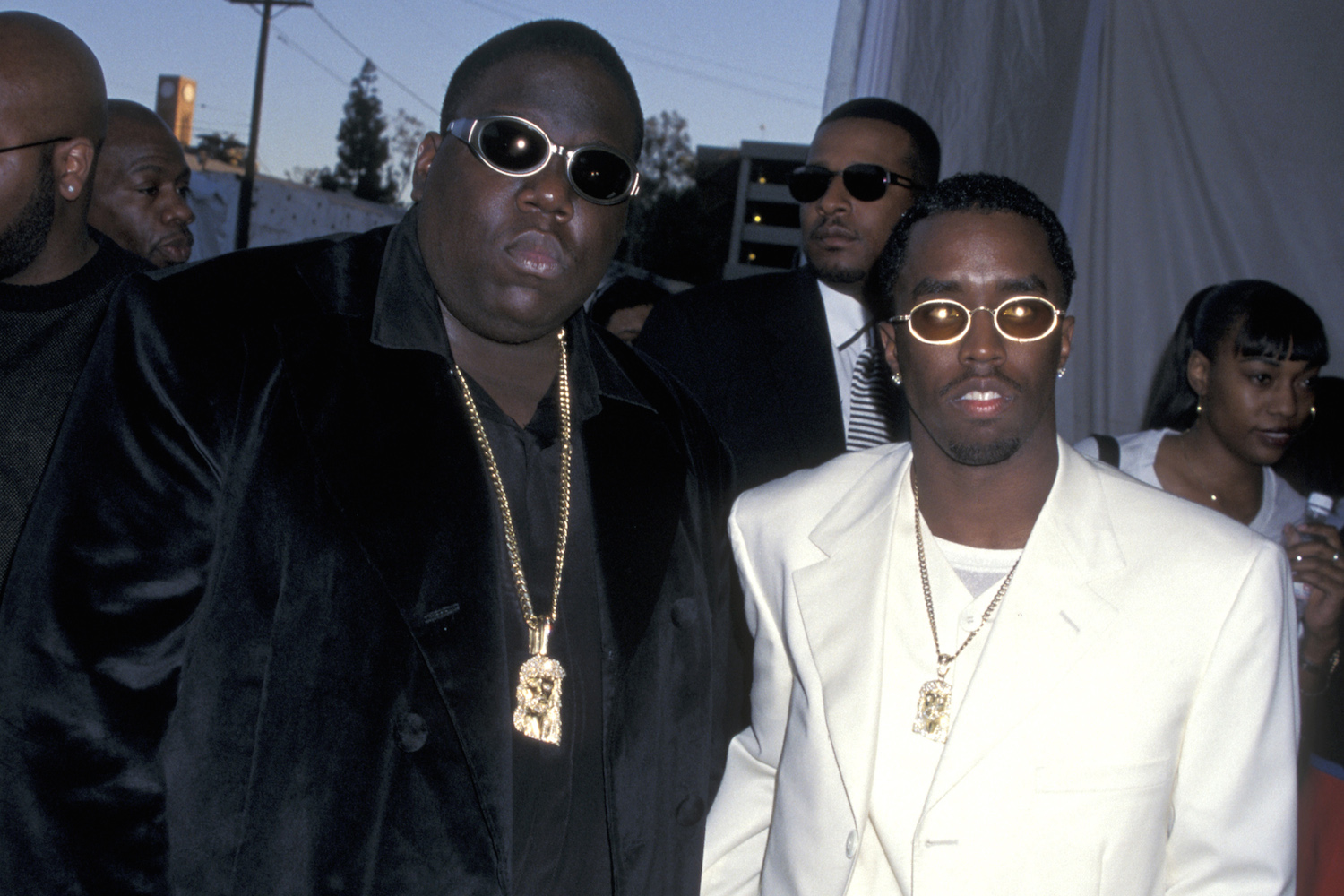

08. Bad Boy

Sean Combs is a businessman first and foremost. He has unabashedly stated this himself with his famous line, "Don't worry if I write rhymes/ I write checks," on "Bad Boy For Life" off of 2001's The Saga Continues. He has reinforced those words with his lucrative label, grubbing publishing rights starting as early as 1998 and continuing just this year, and putting his name on seemingly anything, including clothing, liquors, cologne, water, and much more. Combs knows how to endorse and move products extremely well, and his artists are seemingly simply treated like products.

The bulk of Bad Boy's strength comes from the early to mid '90s, off of the beginnings of Biggie Smalls and Craig Mack, but as Biggie so cleverly said, he had "more Mack than Craig" and was the main reason for Bad Boy's early success. The residual effects of Biggie's success and Combs' vision led to the ascension of rappers the LOX, Lil' Kim, Ma$e, Black Rob, Shyne, and even Yung Joc. R&B acts like Faith Evans, Total, 112, and Carl Thomas also rode the wave from the splash made by the Notorious B.I.G. To date, Bad Boy has 39 plaques to its name, 19 of which are by rappers or are compilations featuring rappers. The commercial success of Diddy's business mind is undeniable.

Culturally, Bad Boy's position was much more important. Bad Boy's glossy soul and disco samples paired with Smalls' incredible gift for storytelling and raw lyricism were a direct contrast to the reimagined P-Funk of Dr. Dre and vivid gangster raps of Snoop Dogg and Tupac Shakur. Combs was also the smooth, savvy businessman with a penchant for sharing the spotlight with his artists, while Suge Knight employed a "get down or lay down" policy in his business dealings and was more behind-the-scenes muscle. The West Coast was clearly running the rap game with the success of Dre's The Chronic, Snoop's Doggystyle, and Tupac's Me Against The World and All Eyez On Me. Though Bad Boy was rather passive in their side of the beef, Death Row's acknowledgement of a clique that was formidable enough to warrant diss tracks, shade at award shows, and shots in interviews was a vote of legitimacy.

A revamped Bad Boy has enjoyed decent mainstream success past the turn of the century with acts like Danity Kane and Janelle Monâe, but their presence in the rap game has fallen off. French Montana, Machine Gun Kelly, and Young Chris are the rappers currently listed on their roster -- a far cry from those who lifted the label to prominence.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

07. Young Money

There is no telling what will happen to Young Money and Cash Money in the next few months and years to come. But since its inception in 2005, Young Money has had a consistent presence on the radio and moved a notable number of units in a shifting climate where record sales are dismal. The Young Money core members of Lil' Wayne, Drake, Nicki Minaj, and Tyga have registered 143 songs on the Billboard Hot Hip-Hop/R&B charts, and this number is not accounting for their numerous features that have hit the charts as well. It is nearly impossible to turn on the radio and not have Drake's nasally tone, Nicki's bonkers flow, or one of Weezy's ever-changing deliveries invade your brain through your ears. Young Money has also sold more than 18 million records, including nine #1 albums, in a time where artists eat more heartily off of touring than record sales.

Lil' Wayne is also quite the talent scout. He pulled together a reinvented goofy actor from Canada (Wheelchair Jimmy was my guy though), a Trinidadian immigrant with a failed acting career, and a kid who may or may not be from Compton and turned them into the radio-ruling, record-moving clique that they are today. Not bad, Mr. Carter. For such a hodgepodge group, there is a unifying factor that you can't quite put your finger on. There was not even the slightest inkling Wayne's signees would be as successful as they are, as their sounds and styles were completely different before linking with Wayne. Drake was making (arguably better) music with his Canadian compatriots and rapping over Jay Z and Kanye instrumentals when Wayne found him. Nicki Minaj was a raw Queens emcee with a vicious flow and lyrical prowess before she turned into the crossover pop-hop queen she is now. Wayne may not have seen this potential for what it has become, but one thing is for sure: He knew there was money to be made.

With the Lil' Wayne vs. Birdman saga still unfolding, it's unclear where Young Money's artists will land, but the members doing the heavy lifting are successful enough to leave if the label were to dissolve. Drake can have surprise albums go platinum, and OVO Sound is gaining strength. Nicki Minaj's personal brand has successfully diversified with perfume, clothes, and TV. Tyga can most likely find a comfortable situation on another label if need be, although he has taken Weezy's side in the beef. This whole thing is ugly, but the dust can be easily swept aside when it settles.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

06. Cash Money

Excuse me as I date myself, but I definitely had braces with gold brackets because of Cash Money. The purveyors of bling were successful in "taking over for the '99 and 2000" -- as Juvenile said on "Back That Azz Up" -- and much further beyond those years. Though Cash Money was founded by Birdman and brother "Slim" only a year after Master P's No Limit imprint in 1991, it took longer for the label to begin to find mainstream success. The first wave of Cash Money artists like U.N.L.V. (Uptown Niggas Living Violently), Kilo G, Lil Slim, Pimp Daddy, and PxMxWx were never more than locally revered at best. It was the second wave of the Hot Boyz (B.G., Lil' Wayne, Juvenile, and Turk), the Big Tymers, and producer Mannie Fresh who would constitute what Cash Money would become.

Cash Money boasts 32 gold and platinum albums collectively to date, and even if Drake and Nicki Minaj are considered Young Money rather than Cash Money, the number is still an impressive 25. The Hot Boyz, both as a group and individually, were no strangers to the charts, as several of their hits appeared on the Hot 100. Cash Money even got clubs and house parties cracking on the East and West coasts, as there is still love for cuts like "Nolia Clap," "Back That Azz Up," "Bling Bling," and "The Hot Boyz (Remix)" featuring Missy Elliott at throwback parties.

No Limit opened the door for Cash Money by making the country pay attention to the South as more than slow half-steppers, but Cash Money took it a step further by showing the South could set trends. Many blame Cash Money for grabbing the first shovels to dig hip-hop's metaphorical grave with their materialistic rhymes and Mannie Fresh's catchy but simplistic beats, which moved away from the tradition of sampling. However, the sound was distinctly Southern in nature, and it is undeniable that the country moved to it.

The lawsuits and ugly back-and-forth of the current feud between Birdman and Lil'Wayne, and by extension Cash Money and Young Money, may have cast a shadow of uncertainty over the future for both labels, but Cash Money's legacy as a commercial force is cemented.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

05. No Limit

Percy "Master P" Miller came a long way from selling tapes out his trunk in Richmond, CA. In an interview with VladTV last year, Miller referred to himself as "the Michael Jordan of street hip-hop" and claimed to have sold more than 75 million records on his No Limit imprint, ultimately losing count of the exact number. Considering he sold more than 11 million albums himself, and he released more than 100 albums even before rebranding as No Limit Forever in 2010, that number seems fairly accurate. Among some of the best-selling artists are: Mystikal (5 million), Snoop Dogg (4 Million), TRU (3 Million) Silkk The Shocker (2 million), and C-Murder (1.5 million). There is also no way of knowing how many tapes and CDs he sold on the street in five years before linking with Priority Records in 1995.

What is particularly impressive in Miller's case is that he managed to run a modestly successful storefront (No Limit Record Shop) in Richmond from 1990-1995 before even signing a distribution deal. The music was distinctly Southern despite his locale, and the South received minimal mainstream attention in the early and mid '90s due to the domineering presence of the East and West coasts. Miller was integral in the South's invasion of the mainstream airwaves and paving the way for Cash Money and many Southern artists who would enjoy commercial success.

A close examination of No Limit's sonic fabric reveals threads to the Casio keyboards of Atlanta's snap music movement, Southern strip-club-turned-night-club music, the aesthetic of Cash Money's bling era dominance, and even the theremin popularized by West Coast gangster rap post-N.W.A. The molasses-thick Southern drawls, accents, and slang slowly drizzled all over the tracks readied the country for the Southern artists who would follow, despite the rhymes not being very adept.

An additional testament to Miller's business savvy was No Limit Gear and No Limit Sports. Though a few rappers and record labels had clothing lines prior to No Limit Gear, No Limit Sports was the first of its kind, representing Paul Pierce and Ricky Williams before folding. No Limit was not only a pioneer in what would become the Dirty South musically, but the label also set the tone for the diversified moguls and labels of today.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

04. Roc-A-Fella

With 18 plaque-earning albums on the wall and a string of radio hits in the early 2000s, Roc-A-Fella records carried the torch for the East Coast along with Ruff Ryders. Shawn "Jay Z" Carter, Damon "Dame" Dash, and Kareem "Biggs" Burke launched Roc-A-Fella in 1996 as an independent outlet for Jay's classic Reasonable Doubt. Off of Jay's strength as an artist, the label signed a deal with Priority Records and proceeded to build a roster that would include N.O.R.E, M.O.P., Cam'ron, the Diplomats, Beanie Sigel, Freeway, Young Gunz, Kanye West, and even Ol' Dirty Bastard before he passed.

The bulk of Roc-A-Fella's success comes from Jay Z and Kanye West, but it was truly an East Coast institution that extended beyond what Ruff Ryders was doing in New York. The Diplomats would put Harlem back on the map after Ma$E did his thing for Bad Boy, and Jay obviously represented Brooklyn, but the Philly wing finally gave their city a scene that would sit somewhere between the bubblegum of Will Smith and the revered but not necessarily commercially successful jams of the Roots. Kanye West would even bring attention to Chicago with the school series albums.

Production from Swizz Beatz and Just Blaze would come to define the early-2000s' Roc-A-Fella sound, and the addition of Kanye West would catapult the sound in the mid 2000s. This gave the Roc a varied sonic aesthetic that included the genius sampling of Kanye rooted in the old school, the precisely chopped, quick MPC hits of Just Blaze, and Swizz Beatz's knack for using what would seem to be a weird and annoying noise as the intoxicating drive for a beat. The diversity of the sounds was unified by the raps of the nuanced hood-dweller no matter what region they came from. Cam'ron had the whole pink thing popping before Nicki Minaj, embodying Harlem's flash, Beanie Sigel had the "Broad St. bully" image, Freeway was the enlightened, kufi-crowned knowledge dropper, M.O.P. had the hyped party jams, but it was all East Coast, aside from Kanye's Midwest twang.

Jay-Z's departure to become president and CEO of Def Jam, and the mess that ensued with Dame and Biggs, eventually killed the label until Dame resurrected it in 2010, but Roc Nation has carried the torch into the 2010s.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

03. Death Row

Despite its heyday coming to an abrupt end, Death Row sold a lot of records in the short period from its inception in 1991 to Tupac's death in 1996, and even saw success into the new millennium with a couple of posthumous Tupac releases and Snoop and Dre reissues. With 13 diamond, platinum, and gold albums and soundtracks collectively from '91-'98 Death Row saw the most success of any hip-hop label in the shortest amount of time. When LA artists take over the NY hip-hop institution that is Hot 97, there is a high level of dominance assigned to their national radio presence. Had Tupac lived, he was certainly poised for superstardom with even more movies and much more music to be created (and music from the vaults to be released).

In addition to Death Row's commercial success, what made the label so intriguing was its image. Capitalizing off of Dre's gangster N.W.A. roots, Snoop's Long Beach upbringing and Crip affiliations, Pac's T.H.U.G. Life movement and villain movie roles, and Suge Knight's Blood affiliations and criminal tendencies, Death Row was simply not the label to fuck with. The Bad Boy beef only bolstered this image, as Tupac made all sorts of claims about sexual affairs with Faith Evans, threats on Biggie Smalls' and Puff Daddy's lives, and one of the best diss tracks of all time in "Hit 'Em Up" without any real response from Bad Boy through any outlet. All of these elements were present in the music, and Dre's innovative reinterpretations of funk as the backdrop for lyrics with vivid stories that felt all too real at the time created an irresistible allure.

As quickly as Death Row came into its reign, its demise and dissolution came even quicker. Tupac's death in 1996, Dre's departure to begin Aftermath in the same year, Snoop's departure to join No Limit in 1997, and Tha Dogg Pound not quite living up to mainstream expectations led to some dismal years for the label. Although able to subsist off of posthumous Tupac releases, Knight was unsuccessful at assembling a comparable roster to continue the original momentum. It seemed he was grasping for any type of lifeline, signing Petey Pablo, Lisa "Left Eye" Lopes, MC Hammer briefly, and Crooked I before eventually selling for a pretty penny to Entertainment One Music (formerly known as Koch Records) in 2013.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

02. Aftermath

Easily the label with the most success and longevity on the West Coast, Aftermath has earned platinum plaques or higher on 16 of its 22 releases in nearly 20 years of operation. If King Midas' touch turns things to gold, then Dr. Dre has him beat.

Dre's ear for talent is debatably unparalleled, beginning with his foresight to trust in his own abilities enough to leave Death Row without fighting Suge Knight for rights to any of the music he created there. Dre released projects from signed artists sparingly, but made intelligent selections with those releases. Eminem was a huge gamble due to the racial implications his success would bring as a white artist in a black genre, but an endorsement and investment in Em's skills would lead to his eight albums all going platinum or diamond. Dre took on a similar risk in signing 50 Cent after his debut album, Power Of The Dollar, was never released and the Queens rapper created many enemies with those singles that managed to see the light of day. Kendrick Lamar released six mixtapes and an album (Section.80) that only sold 110,000 copies (as of this summer) before his first release on Aftermath (2012's Good Kid, M.A.A.D City) went platinum and its follow-up, To Pimp A Butterfly, debuted at #1 this year.

Aftermath also was the vehicle for taking Dr. Dre's sound national. Before his label, he was synonymous with West Coast hip-hop, though he was never merely a local artist. Producing for Em from Detroit and 50 Cent from Queens solidified the appeal Dre's music would have in different regions across the country while still keeping its definitive West Coast traits. This also kept the West relevant when the South came bursting into the mainstream, and Ruff Ryders and Roc-A-Fella were continuing and modifying the East Coast tradition.

On his brand new album/soundtrack, Compton, Dre emphatically asks, "Who you know came this fuckin' far from the fuckin' bottom?/ 30 years in this bitch and I'm still here/ decade after decade." With his business sense and platinum touch, another decade of relevance is not farfetched.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

01. Def Jam

Def Jam has sold more than 100 million records in 32 years of existence spanning from the very beginning of rap to artists that maintain the label's relevance today. It is by far the most successful and longest-running label in hip-hop history. From humble beginnings in an NYU Dormitory with Rick Rubin and Russell Simmons, it has turned into what many consider to be a major label despite its technically independent status.

No label is without its flops, but from LL Cool J to Vince Staples, Def Jam spitters have a cachet that is not afforded to artists on any other label. Def Jam's cultural significance is impossible to quantify; it includes everything from the quintessential crossover rock/rap hybrid of the Beastie Boys, the powerful polemic raps of Public Enemy, the smooth tunes of EPMD ... and so many others that it would take forever to name them all.

No other label can boast playing an integral role developing rap in its infancy while still housing artists that push the boundaries of the genre today, both culturally and sonically. Rubin's ear as a producer was just as essential on the Beastie Boys' License To Ill as it was on Yeezus more than 25 years later. While he is only one half of the founding duo, his presence in rap yesterday and today is symbolic of Def Jam's lasting influence. Simmons also helped establish the rap mogul paradigm, for better or worse, with Phat Farm, Def Poetry and Comedy Jams, international branches of the label in Japan and Germany, and even his latest partnership with Visa for the RushCard. Though the imprint's presence is much smaller than in earlier decades, it has yet to be left completely out of the picture.

Even through a few reorganizations and changes in leadership, Def Jam thrives, and it seems there is no stopping it in the near future. It will be a sad day for rap when Def Jam shuts its doors. As of now, though, that day remains in the distant future.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]