In the late '90s, nobody wanted to get left behind. This was the electronica moment, the time when plenty of press and industry types were predicting the imminent takeover of dance music, which people really believed would radically shift the axis of power in the music universe. That didn't happen until years later, and when it did, it would take a completely different form from what everyone was imagining in the '90s. (Twenty years ago, nobody saw the Chainsmokers coming.) The next great wave was coming, but it wasn't dance music; it was the teenpop and nü-metal that were just bubbling up at the time. In the moment, all that happened with electronica, at least in North America, was that the Prodigy and the Chemical Brothers got some fawning press and went into light rotation on modern-rock stations, and a few car commercials suddenly sounded sleeker. In a weird way, that moment's greatest legacy might be all the aging pop artists who were suddenly doing everything they could to streamline and modernize their sounds.

This was the era of U2's Pop, of David Bowie's Earthling, of the Smashing Pumpkins' Adore, and even, to some extent, of R.E.M.'s Up and Janet Jackson's The Velvet Rope. A sound was emerging. Projects like this would attempt to integrate dance music in slick and tasteful and evocative ways. Their synths would pulse and burble, and their drums would pound, but they'd do it lightly. Processed guitars would float through the mix. Sometimes, you'd hear a light skitter of jungle-music drums. Sometimes, you'd hear a tabla. These artists were not, by and large, interested in getting their stuff played at nightclubs or raves. Instead, the deep atmospherics of Massive Attack were a key influence. They wanted to nod toward club culture without giving in to it completely. These sounds were supposed to color their songs, not reshape those songs completely. If these artists were trying to sound like the future, though, they instead made music that was stuck completely in the moment, that could never come out at any point other than the late '90s. And other than maybe Jackson, nobody even came close to doing that sound as well as Madonna on Ray Of Light, an album that turns 20 tomorrow.

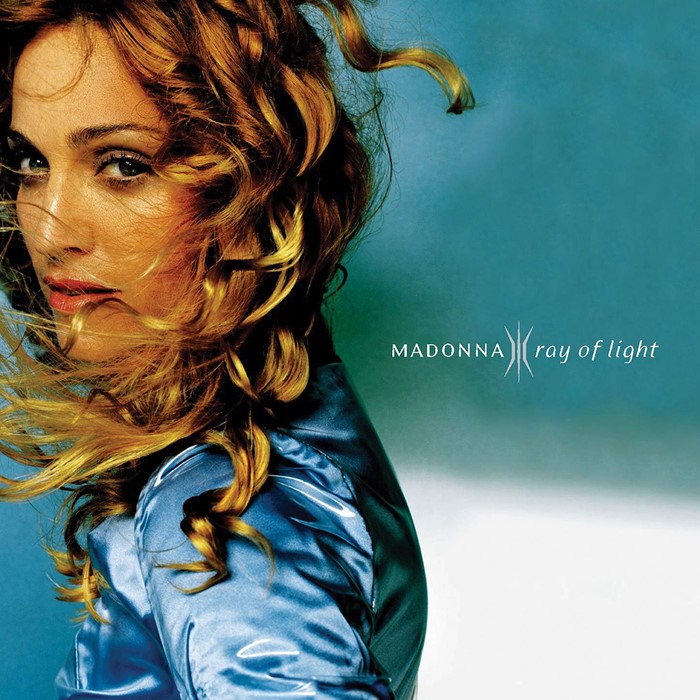

Ray Of Light was a reinvention for Madonna, only the latest in a career full of them. For her previous studio album, 1994's Bedtime Stories, she'd worked with producers Dallas Austin and Babyface and embraced the soft, tender sounds of mid-'90s radio-ready R&B. When it came time to record Ray Of Light, she started out working with Austin and Babyface again but scrapped what came from those sessions. Instead, she linked up with William Orbit, a UK producer who'd remixed a couple of her singles and whose sound, a warm and tasteful dance-music thump, was what all Madonna's fellow superstars were chasing at the moment. Madonna and Orbit worked together closely, with Madonna using Orbit's sonics to explore some of the deeper, heavier things that were on her mind at the time.

When Ray Of Light came out, I had friends who bashed it constantly, dismissing Madonna's forays into electronica as pure trend-chasing. They were wrong. We argued a lot. Madonna was trend-chasing, at least to some extent, but she was also one of history's greatest trend-chasers, a cultural chameleon with impeccable instincts. But also, dance music was nothing new for Madonna. When she first arrived, she was a pure product of New York's post-disco club culture. Early on, she worked with dance-savvy producers like Jellybean Benitez and Reggie Lucas, and a song like her 1982 banger "Burning Up" was about as good as club-oriented new wave ever got. She never left dance music behind, either. In 1990, she hit #1 with "Vogue," a straight-up house anthem that both plundered and saluted the gay club underground. Later that same year, she hit #1 again with "Justify My Love," which basically sounded just like Madonna doing Massive Attack, even though Blue Lines was still months away from release. In 1995, she got Massive Attack themselves to produce "I Want You," her contribution to a Marvin Gaye tribute album. Musically, then, Ray Of Light was a logical and easy transition.

Ray Of Light sounds smooth. Madonna had never been as vocally assured as she was on that record. She'd done serious vocal work to prepare for her role in the musical Evita, and on Ray Of Light, she delighted in the subtleties she'd never been able to show. She could've used her voice like a bazooka, they way she did in Evita. Instead, she went quieter, adding accents and shades. The most haunting thing about "Frozen," the album's lead single, wasn't the way the strings echoed Madonna's Bedtime Stories collaborator Björk, though that was definitely cool. Instead, it was the way Madonna could hum, hitting deep emotional chords without even needing to form words.

"Deep emotional chords" were what she was going for, too. Madonna had always been a quietly powerful singer on ballads, communicating serious romantic helplessness on songs like "Crazy For You" and "Live To Tell." With "Papa Don't Preach," she laid out a whole movie-worthy narrative, bringing sincere empathy and heartbreaking hope to her character's predicament. Ray Of Light found her in another zone. She'd just become a mother, and she was suddenly less interested in sex and partying, more interested in exploring her own spirituality. (It wouldn't stick. She was back to sex and partying on her next album, 2000's Music, which ruled.) On Ray Of Light, Madonna had one song for her daughter Lourdes, born just a few months before the album came out, and another for her mother, who'd died when she was a child. And even the title track, the album's one club-ready outlier, was more a cry of vaporous freedom than a hedonistic anthem. I still don't know what "zephyr in the sky at night" means, but goddam, it sounded great.

At the time, Madonna was also famously flirting with Kabbalah and with Hinduism, and a song like "Shanti/Ashangti," wherein she chants in Sanskrit over quasi-Eastern flutes and drums, sounds pretty clueless today. It honestly sounded pretty clueless at the time, too. I learned pretty quickly to skip over the parts of Madonna's interviews where she'd talk about her newfound spiritual fixations, and I learned to skip "Shanti/Ashangti," too. Elsewhere on the album, Madonna would make reference to the concepts she was just learning about. I never got anything from that stuff. Maybe it wasn't yet a cliche for a rich, aging white woman to talk about those ideas, but it wasn't really that interesting, either. What was interesting was that Madonna -- who, fairly or unfairly, was regarded as an icon of '80s plasticity -- was even searching for deeper meaning. The type of fame that Madonna had -- galactic, overwhelming, so dominant that she couldn't go outside unaccompanied anywhere in the world -- made for an unnatural and unhealthy way to live. So maybe that spirituality was her way of dealing with it. And you don't have to be too impressed with that side of Ray Of Light to understand that it worked. Madonna found a way to cope. She's still with us, and her closest '80s-superstar peers are not.

Earlier this week, Madonna's longtime manager Guy Oseary posted on Instagram to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Ray Of Light, and Madonna herself left a comment on that post that grabbed a lot of attention: "Remember when i made records with other artists from beginning to end and I was allowed to be a visionary and not have to go to song writing camps where No one can sit still for more than 15 minutes." And just like that, the world gained a new understanding on why Madonna's last few albums have been so tepid and passionless. Ray Of Light is a flawed album, one very much stuck in its moment. But it's also worthy and compelling and driven by Madonna's own thoughts and ideas. Maybe she's got another one like that in her. Maybe more than one. And maybe, if things shake out right, she'll even get to make them.