The late '90s were a heady time for hopeful, plucky alt-rock hits that would forever soundtrack senior class montages, and I’m not sure I’ll ever understand why. Maybe it was the economy or the internet boom or just the general laissez les bons temps rouler vibes of the last days of Clinton that made opportunity seem more abundant and an uncertain future feel less frightening? But the most truly inspiring valedictory speech of the time? That came in the form of an emo thrasher in weird time signatures made by some guys who barely made it to the podium and urged all the outcasts and burnouts to bet on themselves: "We’ve got a lot of great mistakes to make/ We’ve got a lot of chances to take/ So let’s take our time and then hurry."

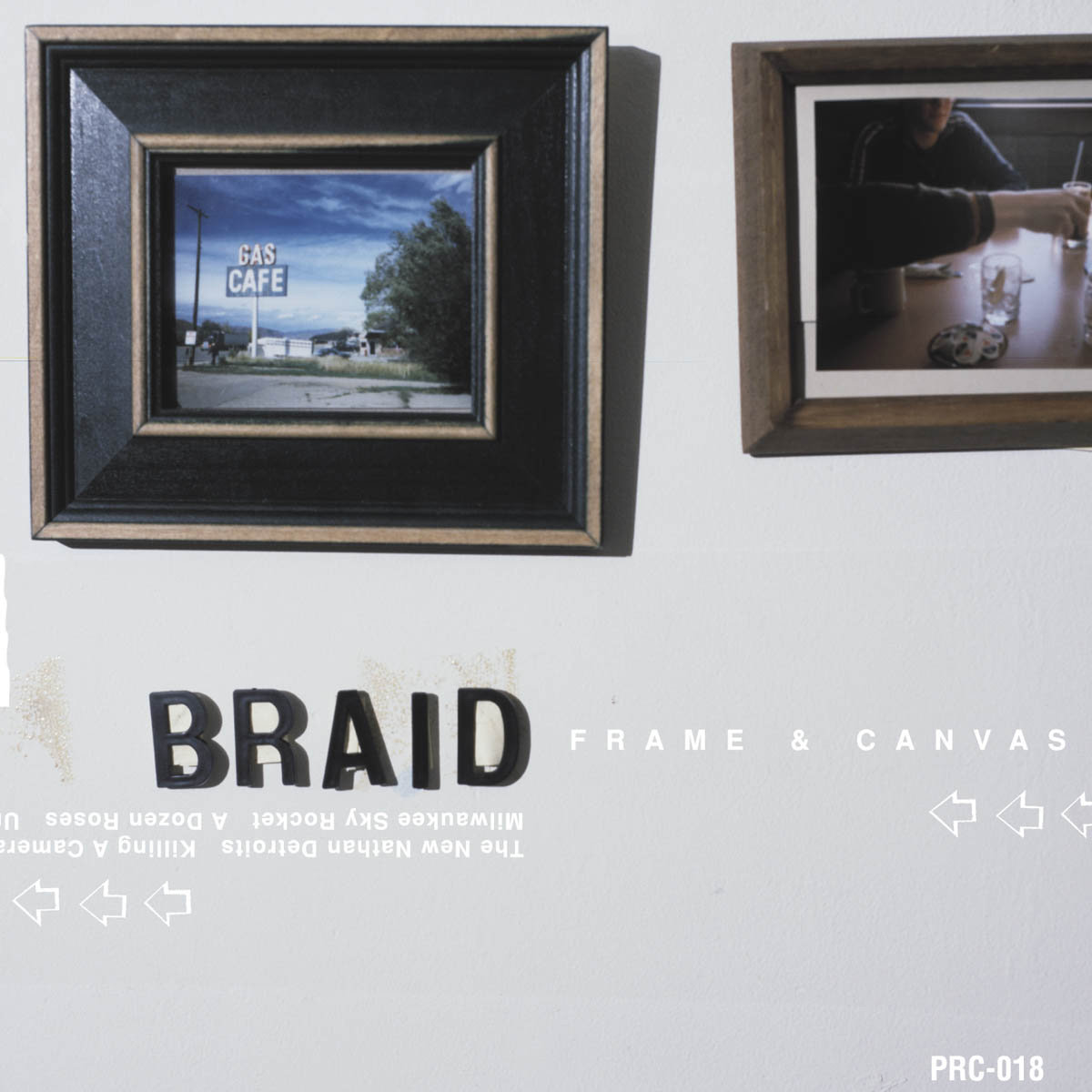

Bob Nanna begrudgingly graduated from the University Of Illinois in 1997 before Braid drove to Inner Ear Studios in DC to record their classic third LP Frame & Canvas, which came out on April 7, 1998 -- 20 years ago this Saturday. Meanwhile, to quote Kanye West, co-guitarist/frontman Chris Broach decided he was finished. "The New Nathan Detroits" is presented as a heart-to-heart between the two Braid vocalists and their parents about their job prospects, whether they’re going to pursue stable careers still available to college grads in those days or go all-in on their beloved emo band that had no real shot at mainstream success or acceptance but their entire scene cheering them on. "There's so many things going through your head at that point and it's not just, 'What will people think? Is it the right thing? Is it really what I want to do?'" Nanna tells me over the phone. "Our thought was, 'This is the time to make these moves and do these things that make us happy and make us feel fulfilled.' And we can't really care too much about what other people think."

Whatever tension and ambivalence is generated by Braid’s taut post-hardcore assault and the serve-and-volley vocals of Broach and Nanna is negated by a repeated, shouted "GO!" -- the sound of a band that no longer had any use for a backup plan.

Frame & Canvas is a crucial document not just of second-wave emo, but a thriving ecosystem of indie rock centered around Champagin, Illinois in the mid-1990s. On their 1995 debut, Braid were teens with unlimited access to cheap beer at a friend’s recording studio, and Frankie Welfare Boy Age 5 sure sounds like it -- a 26-song, 65-minute behemoth where Braid are only intermittently and vaguely interested in things like "singing on key" and "production values." The Age Of Octeen followed a year later, underappreciated in its time, but clearly a dry run for what came next. Broach and Nanna describe Frame & Canvas as an album made for their friends, about their friends -- a show of solidarity with locals Castor, Compound Red, and especially Sarge, a friendly flex on their ascending peers in Get Up Kids and Promise Ring and a justification of their existence to Champaign’s "old guard" in Hum, Poster Children, and Menthol.

It’s also the album that put Polyvinyl on the map; Matt Lunsford and Darcie Knight had started the Polyvinyl Press as a self-published fanzine and helped set up the first Braid show in 1993 somewhere in Danville, a city of 33,000 about 45 minutes away from Champaign. Along with Rainer Maria’s Look Now, Look Again and American Football -- another masterpiece inspired by impending graduation from U of I -- Frame & Canvas established Polyvinyl as a stronghold of Midwestern emo. In the time since, they’ve built a diverse catalog of past and future indie rock canon from of Montreal, Japandroids, Alvvays, Beach Slang, Jeff Rosenstock, and Jay Som, amongst others. And yet, they’ve never strayed too far from their roots -- this year, they’ve signed the rebooted Pedro The Lion and the Get Up Kids.

Any "greatest emo albums ever" list worth a shit will probably include Frame & Canvas in its top 10, and it’s usually in the lower half. Braid never achieved the commercial success of the poppier Get Up Kids or the Promise Ring and, perhaps due to their intermittent reunions shortly following their initial breakup in 1999, Frame & Canvas lacks the mythic aura surrounding the likes of Diary, American Football, and Shmap’n Shmazz; if it’s any consolation, their Will Yip-produced comeback album No Coast bested the American Football sequel.

The album's influence is also harder to track, for it sits at a nexus point between the more tuneful strains of late-90s Midwestern emo and the D.C post-hardcore of Fugazi and Jawbox, whose J. Robbins recorded and mixed Frame & Canvas in the span of five days. But on a personal level, it’s my Exhibit A for the spirit and vibrancy of this kind of music that makes it the most motivational kind of indie rock I know of -- leaning back with all of your self-doubt and uncertainty against a slingshot and getting propelled ever forward by pure nervous energy. I get a lot of shit done on days when I listen to Frame & Canvas.

When it was written, "The New Nathan Detroits" made it seem like Nanna and Broach had to choose between putting their kids to bed or putting on for the kids in their scene. Twenty years later, they’ve done both, and they continue to make new music in various projects; Nanna’s band Lifted Bells just released their new album Minor Tantrums on current emo/punk powerhouse Run For Cover, while Broach’s electro-pop project SNST dropped Turn Out the Lights (also produced by Yip) in November.

The due date for Broach’s third child passed the day before we spoke on the phone, and his time window was tight. He had taken his two kids to the park for the usual "bunny rabbit thing" on the Saturday before Easter, when a fellow father recognized him. It’s not a regular occurrence, but it happens sometimes. "He started to talk about emo after that," Broach said, and whatever weirdness came of the conversation was overruled by the fact of the matter: They were two suburban Chicago dads who lived in the same area and liked Braid. They exchanged phone numbers.

Nanna interjects: "I can’t believe the Easter Bunny is a Braid fan!"

Nanna isn’t exactly getting Broach’s story straight, but that’s Braid for ya -- as vocalists and lyricists, the two attack the same subject matter from different perspectives, dueling and not always in harmony (even though Broach is usually the more excitable one on record). As such, the story of Frame & Canvas is best told as a conversation between the two, a fond and occasionally foggy recollection of the chances taken and mistakes made.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

"The New Nathan Detroits"

STEREOGUM:The chorus -- "My son, have you grown? Make a home and put the kids in their bed" -- seems to indicate that your parents weren’t too stoked on your life plan.

BOB NANNA: I graduated in 1997 and we drove to DC to record the record in December. I was already out at the time so all the writing of the record came at the time when we were finishing school which I kinda...did not give a shit about. All I was trying to do is make my parents happy. They said, "Do whatever you want with your life, but at least graduate." I was like, "Done, I can do that."

CHRIS BROACH: I wish my parents had said that -- they kinda did, but I wasn't listening. I gave less of a shit, enough little shit that I dropped out once Braid took on full steam. Once we started playing in a band, that was what I wanted to do anyway. My whole second semester, I stopped going to class and that was that. I went back later to finish the degree.

NANNA: We were all different ages. Chris was a year younger, [bassist] Todd [Bell] was three years older. It's funny, we were in different age groups but we were all going through the same thing and experiencing this new world together. That's where the headspace was, this crucial time when you have to decide, "Do we want to join the workforce, start the next chapter of family and getting serious with a career? Or do we take the opportunity to really explore what we can do with the band?"

BROACH: I don't think any of us were in the family headspace. I was waiting tables in between tours and it was like, "This is what I want to do." And this is what we all wanted to do, so that's why we said "let's go" and the next year, we were on the road for 8-9 months.

Full disclosure, before this call, I listened to the album and read the lyrics again to re-familiarize myself with the references. I'm looking at the part, "It’s pointless to play if you don’t get paid," for example. I remember us literally saying that -- we can't go play for free, people were asking us to play festivals and we're like, "No."

NANNA: It was double-sided, because that was what people were telling us and the impression you get from parents, like, "What the fuck are you dong, you're not gonna make any money. You're not gonna set yourself up for any kind of secure future."

STEREOGUM:"On the fiftieth plane to Champaign" -- that’s a tiny airport. How many times did you actually use it?

BROACH: I think I flew into it once or twice on a tiny airplane. Most of the flights were van rides.

NANNA: Or the train. The "plane" was better with "plain white paper."

BROACH: Imagery!

NANNA: The mode of transportation will change because it sounds better.

"Killing A Camera"

STEREOGUM: This is the one with the album title in the lyric, "The new slang in frame and canvas." Did the lyric come first or the album title?

NANNA: That was Chris’ idea to name it Frame & Canvas, and...I don’t remember, it was some kind of art school thing. And by the way, the lyric "new slang" ... do you think the Shins took that from "Killing A Camera"? We played with one of their bands, Scared Of Chaka [which featured future Shins member David Hernandez]. Whatever, it doesn't matter.

BROACH: They could’ve, but [that term] is easy to come up with anyway. I honestly don't remember...there are a lot of things I don't remember.

NANNA: It was some assignment you had in art class, and I thought, "Yeah, that’s gotta be it," because it set the stage nicely. The title was there before the lyric.

BROACH: It was a blank canvas to frame out, "Here it is, this is what we're doing and this is what's inside of it and what's on top of it." That's dumb, but...I went to school for art and photography and then I thought, "I just want to do music, that's it." And then I got a degree in psychology later for no reason.

STEREOGUM: That lyric is preceded by "We sang it for Memphis." Did that city have any particular relevance to Braid at the time?

NANNA: Memphis just works with "canvas."

BROACH: Wordplay!

NANNA: I'll change the location if I have to.

BROACH: It could've been Minneapolis.

NANNA: But that’s too many syllables.

"Never Will Come For Us"

STEREOGUM: "And it doesn’t get played on the radio" -- was there still a sense of honor of making music that wouldn’t get on the radio or MTV back in 1998?

BROACH: We knew we were playing music that wouldn't get on the radio. Back then, when I'd meet people and they'd ask what you were listening to and that was the only thing that mattered: "You wouldn't know it, they don't get played on the radio." I don't know if that's where Bob's coming from, but it's again one of those things where, "It's not gonna get played on the radio, but whatever, let's do it anyway."

STEREOGUM:"Our friends say 'way to go' and where to go" -- were Braid a thing on the Illinois campus at the time?

BROACH: Everywhere we played, people came out and we had an awesome time. We played a lot of house parties and things like that, and it was all our friends freaking out.

NANNA: When we first got to Champaign in 1993, there was no DIY scene there. It was all at the bars, and the bars were 19 and over, so we would have to stand outside to watch Archers Of Loaf or Seaweed, we couldn't even get in. So one thing that I think Braid helped with and got started was bringing the house show mentality that Chris and I had separately experienced in Chicago in the suburbs. It was [Nanna’s former band] Friction and Cap'n Jazz doing shows at VFWs and people's houses, we were just, "There's no way we're gonna play the Blind Pig and Mabel's."

BROACH: They weren't gonna let us play anyway.

NANNA: So we just started to do shows at our friend Rachel's house, and Todd might've lived there too, and every band that would come through would play there.

BROACH: We kinda brought ‘em all through. Someone got someone's number and in those days, you passed around numbers -- "this person does house shows, in this city" and eventually people started calling. Or we'd be on tour and we'd say, "You should come through Champaign, when you're here give us a call."

NANNA: Email was in its infancy.

BROACH: You would call and literally be, "It's this guy from this band, I got your number, are you still doing shows?"

"First Day Back"

STEREOGUM:This was the first single from Frame & Canvas...

BROACH: "Single"...it's a loosey-goosey sort of term. Braid never made a video. We tried to do one.

NANNA: We did, for "American Typewriter." [sarcastically] That classic Braid song that we play all the time.

BROACH: We played it four times live, right?

NANNA: [Drummer] Damon [Atkinson] never learned it.

STEREOGUM: That’s probably for the best, I’ve watched a lot of videos by your peers from that time and they haven’t aged well at all.

BROACH: We dodged a bullet. On New Year’s Eve, I did a DJ set in Milwaukee and I was hanging out with Dan Didier [bassist from the Promise Ring]. We put on old Promise Ring videos and just laughed. All of us laughed out loud, it was super funny. I agree they didn't age well, but they're super fun to watch.

STEREOGUM:"On the middle of the stage, there’s a girl with a guitar" -- is that referencing anyone specific?

NANNA: I don't think it was explicit, but we were dong a lot of playing and hanging out with Sarge. [Frontwoman Elizabeth Elmore] actually lived with us for a while. The song's not literally about her, but you just can't help but be inspired by them playing. That's where I'm pretty sure the impetus for that line came.

BROACH: Going back to the whole idea that [Frame & Canvas] was about our friends, we were playing with our friends and bringing our friends with us -- "Let's go on tour together!" Elizabeth Elmore from Sarge is a prime example, or Castor, or Compound Red.

"Collect From Clark Kent"

STEREOGUM:This is the most "Midwestern emo" song to me lyrically -- communication breakdowns, long-distance pining and such. Were either of you in relationships while writing Frame & Canvas?

NANNA: I was getting out of one at the time, one was ending.

BROACH: A lot of us were in and out of them. I think we were talking about how relationships suffered because of the lack of communication and ability to communicate. Email was still a pretty new thing, and I remember the question we would ask is, "Are you online at all?" Meaning, "Do you have an email and should we try and stay in touch that way instead of phone?"

That said, yeah, there wasn’t much ability to communicate with significant others -- other than actual letters and postcards from the road. But in some sense, it was good to be less connected and more focused on the music and the thing we were out there doing. It also led to some intense short-term relationships back then, as well -- because you didn’t know when you might see someone again or when you’d be in touch again -- and being in a small scene with similar interests, it was easy to develop short-term crushes. I had a couple of relationships suffer and fizzle back then. Like, leaving for tour while having a girlfriend and coming home without a girlfriend anymore.

The other thing I’ll say, is that if I ever wanted to talk to my family back then, like my mom or dad -- I’d just call collect and they’d accept the charges. It didn’t matter where I was, and since I was always traveling that’s how I got in touch to talk.

"Milwaukee Sky Rocket"

STEREOGUM:Is the Milwaukee in this title a reference to the city or the Avenue that runs through Wicker Park?

BROACH: Damon had just joined the band, he was from Milwaukee. I don't know if it was in honor of Damon.

NANNA: I know it might've been "Sky Rocket" at first.

BROACH: We were shooting bottle rockets at bands. When we would go on tour, we'd throw garbage out the window at the vans. I think we did it with Castor and Sarge, Get Up Kids for sure. If we had a 40-ounce bottle of Coke, we'd toss it out the van so it'd hit their van on the highway.

NANNA: We're not super proud of that. Maybe you're gonna tell the story of you driving and Todd just like handing you a lit bottle rocket from shotgun.

BROACH: "What the fuck!!!" He's like, "Here, hold this for a second."

NANNA: Oh yeah, with Hey Mercedes, we shot bottle rockets at the band Wheat. They were not into it. I didn't go for these shenanigans. But I remember the singer of the band Wheat saying, "Hey, Wheat is not into this," in the third person.

BROACH: I remember coming out to our van one time and the Get Up Kids had literally covered our windows in garbage and beer cans. They were probably the band we did that the most with, it’s all pranks.

NANNA: At that point and time, it was fun. You didn't want to go on tour with a boring band.

BROACH: If a band wasn't into it, we'd say, "Nah, we don't want to tour with them." Nowadays, I would not want to go on tour with a band if they did that to me.

NANNA: Before we move on, Chris -- the line "Impress yourself," I’ve seen that tattoo more than once, so tell me about it.

BROACH: When I was writing lyrics, they sometimes make sense -- for "New Nathan Detroits," I knew exactly what I was writing about. In this one, it was this abstract idea I had, and I'm talking to myself. But I'm also talking to other people too -- "Impress yourself, don't hide, don't try to be someone that you're not, be who you are and be happy about it." If I'm being honest, if you look at Bob’s lyrics vs. my lyrics, Bob's very poetic and amazing, and mine are either more direct or conversational. But half the time, I didn't even know what I was singing about. "This just sounds right and makes sense to me," and I look back and think, "Oh, that's what I was doing."

I was just always trying to keep up, because Bob was so lyrical and I thought, "Damn, I gotta step it up." Also, I know that I had a tendency to just hide and just be afraid. At that time, I was trying really hard to be somebody, because I didn't know who I was still. When you're 20, and you're trying really hard to play music, you're just trying to show people that's what you do. If you look at the lyrical content [of Frame & Canvas], it's the band trying to say, "Yo, we're here and this is what we do, and you better like it! And if you don't, fuck off." But in this context, "Impress yourself" is just, "Do what's right for you," y'know? Be who you are. And actually, be better than who you are. The funny thing about "impress yourself" [starts singing] "Impreeeeeeeess yourself"...is that like an NWA song?

STEREOGUM: That's "Express Yourself."

BROACH: It definitely had nothing to do with that song.

"A Dozen Roses"

STEREOGUM:I understand this is the first song that you did with Damon as the new drummer.

BROACH: He started playing this cool beat...

NANNA: We already had the chords. We were in my parents’ basement and it was just immediately, "We're changing as a band." That thought crossed my mind immediately once he started playing. "This is different."

BROACH: "This is awesome, this is gonna propel us forward. We're gonna take this to the next level."

STEREOGUM:I’d imagine that recording with J. Robbins felt like the "next level" at the time as well. Were you starstruck at all?

BROACH: The answer is yes.

NANNA: Yes. We met him once or twice before we called him and asked if he would [produce Frame & Canvas], but fuck yeah, we were starstruck. He was like a superstar to me. I remember very specifically playing at Inner Ear Studios, and we were recording the song and he was kinda grooving and moving his shoulders.

BROACH: And Bob looked at me and I looked at him, like, "Oh my god, he likes our band!" That's literally what we were thinking, and I’m not kidding.

STEREOGUM:By comparison, when I hear people talking about what it’s like to record with Steve Albini, they say he usually just sets up mics and plays online Scrabble or something the rest of the time.

BROACH: J. is the exact opposite. He got involved. I remember when he got into the studio to play drums at the end of "Breathe In" and I thought, "Holy shit, J. is playing drums on this!" We were just going in there to make noise and he hit record and ran in with us and just started playing. I think it was the most fun I’d ever had in my life at that point.

STEREOGUM:As an up-and-coming band, did he have any advice for you? Jawbox had been a cautionary tale of the grunge era, when all of these bands were getting signed by major labels that didn’t know what to do with them.

NANNA: It wasn't too long after [Jawbox broke up] that we toured with Burning Airlines. If I remember correctly, he didn't really bring it up that much and I didn't want to bring it up.

BROACH: We gave him a card, remember? Jawbox had just broken up recently and we gave him a card that said, "Hey, we're sorry this happened, we really liked Jawbox a lot," and we each wrote our favorite song down on it. He got choked up, put the card away and said, "Thanks guys," and I just remember that seeing he was wholeheartedly choked up. I wrote that "68" was my favorite Jawbox song. That was the greatest song ever to me. Still is.

"Urbana’s Too Dark"

STEREOGUM:Was there much of a difference between the scenes in Urbana and Champaign at the time?

BROACH: Urbana was where all of our houses were, the art kids and music kids. The frats were in Champaign and the old guard, like Hum and Poster Children.

STEREOGUM:Did you interact with the "old guard" at all?

NANNA: Very little, and it changed a bit once bands like us and Castor and Promise Ring started to play this other circuit, for lack of a better word. There started to be more interest from bands like Hum, who had went on tour with Promise Ring. It made us think, "Hmm, maybe we don't have to play this 19+ bar."

BROACH: I think I had recorded one project in [Hum frontman] Matt Talbott's basement.

NANNA: In terms of Poster Children and Menthol, there was little to no overlap.

BROACH: They were doing their thing and we were doing ours, and I think "us doing ours" was because there was no way for us to get on those shows anyway.

STEREOGUM:"So akin to skin/ When boys want in/ Boys will be boys/ Boys will be poison boys" sounds like something you’d hear from an emo band in 2018. The younger people in the scene have become extremely proactive in calling out problematic behavior. What were you seeing at the time?

NANNA: When we going on tour, it was seeing dudes being assholes, specifically to the women. I was having this realization like, I assumed that I was gonna be in a scene where I'm not going to frat parties, I'm going to house shows and hanging out with art people. And then we started going on tour, there were certain bands and situations where I thought, "Man, it's like I'm in a fucking frat house." It's uncomfortable and it was definitely something that was on my mind.

BROACH: I think the title came from our journals because literally, at the time, there was a big movement to put more street lights in Urbana because there were sexual assaults happening.

NANNA: True.

"Consolation Prizefighter"

STEREOGUM:"Windows down, the idiots yell at me, meek on the street" -- even though Champaign had a thriving indie rock scene while you were there, were there times where it still felt like you were engulfed in an enormous Big Ten party school?

NANNA: Maybe initially when I first got there, but it didn't last. And I'll say this, Chris can attest to this: As far as driving down the street and rolling down the windows and yelling at people, that's what we did. We'd pull up to a bunch of frat guys and be like, "Hey, the nerd party is back that way."

BROACH: Todd and I would take the van and go to a frat house and with a carton of eggs, egg the house and drive off. We did it maybe twice. Stupid stuff. So, so stupid!

NANNA: Todd was three years older than us! One of our friends was walking down the street and actually saw the van roll up and Todd roll down the window and yell, "What's in the backpack...POOP?!??"

STEREOGUM:The title of "Consolation Prizefighter" and the line "Tears in the towel, throw it in" -- did you feel like you were in competition with other bands in your realm?

BROACH: I know I wasn't sitting around thinking, "This is the record that people are gonna be talking about." It was like...I think we dd a great job. I was really excited to show it to people. There was definitely some competition, we were friends with the bands we were competing with. It was always, "They did a great record, they wrote a great song, let's make one too." It wasn't overt.

NANNA: It wasn't a situation like, "Goddamn, I can't believe they got on that tour." But if anything [was really inspiring us], it was a band like Hoover or Fugazi, all the time.

BROACH: We were excited about bands that we had no communication with.

"Ariel"

STEREOGUM:This is probably my favorite song on the record, but I’ll be honest -- I have no fucking clue what this song might be about.

BROACH: I don't either.

NANNA: I know for a fact that this was about living in this house with all these people and I was just imagining what if what was happening downstairs was happening upstairs. Honestly, I was thinking a lot about Elizabeth Elmore too, just having this amazing, creative person just downstairs doing something amazing. I remember that going through my head.

BROACH: "'Cause I can’t help it if the songs get hard for you to hear," that sounds like a pretty specific reference, I don't know what it is. For me, I remember Elmore telling us, "Man, when I hear you guys practicing downstairs and you wrote that amazing song, I get mad."

NANNA: I can definitely see that, I know it got to a point where she missed certain things about the way we used to hang out or make music together, that sort of thing. I can't help if this song is referential, it's not like a mean thing...I can't help it, you know.

BROACH: When I'm writing, there's specific references, but certain times, I'll take all the worst or best things that I'm trying to write about from many different situations and throw it all into one song.

STEREOGUM:I’m guessing "Ariel" is similar to the "Memphis" and "plane to Champaign" lines in that it just sounds good.

NANNA: Yup, it's a placeholder name.

"Breathe In"

STEREOGUM:"I drink too much and you sing too much and I think you know it" -- was that more intended as a joke or confession?

BROACH: I know I drank too much back then. It's specific but it's a reference to...I was just overdoing it too much, and I did it forever. I actually don't drink anymore because I overdid it a lot. When you look at these lyrics -- "When I go out, do I look like you do?" -- it's kind of the same as, you're looking at yourself from someone else's eyes or you see someone else and think, "Am I that messed up? Am I doing this as well as somebody else is?" Again, it’s about trying to be the best person. I always struggled with that myself, feeling like what I was doing was inadequate and not knowing that what I was doing was enough for myself. "Hey, look in the mirror, it’s not what you say, it’s how you say it."

NANNA: We were talking about "new slang" -- Piebald definitely took lyrics from "Breathe In" for "It's not what you say but how you say it." [Ed note: the song referenced is "Giddy Like A Schoolgirl."]

BROACH: Did they? I don't know these things.

NANNA: Maybe we were referring to Tim Kinsella? We were having these talks...

BROACH: It could've been. Me and those Kinsella boys and the Cap'n Jazz guys all went to school together, and Tim and I had some times where we weren't really...we were both trying to date the same girl, and that happens when you're a kid growing up. But it's true -- you can be right about something, but you gotta say it right to get through to people. And I was thinking of a right way to get through to myself, in retrospect, 20 years later.

"I Keep A Diary"

STEREOGUM:In contrast to "Ariel," I know what this song is about, and it’s about literally keeping a diary.

NANNA: It is actually! It's an actual entry, 100%. When we were touring around that time, I was writing a lot. Maybe there's an upside of not having a phone to scroll through all the time, or movies even. I read a whole lot more and a wrote a lot, I still have all that stuff, that's why we were able to find lyrics we wrote for this record. Having that entry there definitely drove the idea behind the song, we also wrote it specifically to be the last song on the record too.

STEREOGUM: "I can see exactly/ Just where you ruined me/ 19 I said I hated you/ But kissed you on 22" -- given that this is an actual journal entry, does the person about whom this was written know it’s about them?

NANNA: I don't know. It might be an interesting thing, not just with Frame & Canvas, but with all the records at this time, to talk to people who think they're being talked about in a particular song. There's a [Sarge] song that's 100% about us.

BROACH: I think that she told us...

NANNA: It's pretty obvious, it's called "Beguiling."

STEREOGUM:Do you guys still talk to Elizabeth?

BROACH: On Facebook. She's in the Hague -- I think she's doing legal work for war crimes.

NANNA: She partied harder than all of us, and she was in law school! Talk about someone you're so in awe of and brilliant. "And now they're prosecuting war crimes in the Hague," you know, that old story.

STEREOGUM:On that note, Bob -- Lifted Bells is on Run For Cover, a label with bands who may be in the same position that Braid once were on Frame & Canvas. Have you considered what it might have been like if Braid’s business was out there the same way bands’ are now?

NANNA: We didn’t really have anything to hide, but even back then, there was weird drama, it was always there. But with zines, it took a little longer to get the word out about whatever was going down. Like the More Than Music Fest we were supposed to play; it turned into a huge discussion and then no other bands played.

BROACH: Everyone had driven out [to Columbus, Ohio] to play and it turned into this big discussion. Which is good, because it brought up stuff that people wanted to talk about. It might've been my first experience with what people call "safe spaces" these days. Like, I'd love to play, but also to support [the cause] -- so what should we do?

STEREOGUM: Any final words on Frame & Canvas until we celebrate the 25-year anniversary?

BROACH: I think it's really difficult to be objective about it. I tried today and I read the lyrics, and I thought, "I didn't know those were the lyrics," even the songs we recorded and played live 150 or whatever times. "That's the lyrics, that's cool." But I think for people who aren't just looking for pop hits that are straightforward, I think we were doing something different than other people back, then so that's why it stuck around. When people hear the stuff, it's not like an immediate grabber. It takes a few listens. Someone told me, no one they ever show Braid likes it on the first listen.

NANNA: We didn't plan for it to be the last record, and I wonder if [releasing another album at the time] would've lessened the quote-unquote impact of Frame & Canvas. I'm so happy that people talk about it, because I don't think it's a very easy listen. Not as easy of a listen as some of the other records that were coming out at that time in our scene. It's real difficult! I don't know if I could explain the time signature of "The New Nathan Detroits," and that's the first song on the record. If you can't get into that, you got a whole 40 minutes to go! I'm not surprised it wasn't a huge hit and we weren't playing on TV or whatever, but I'm happy that it's still being talked about and maybe inspiring some people to a small degree.