The horns sit calmly atop the track, precise and regal. The riff they trill out is pretty complicated, but it's also instantly memorable, a melody that seems familiar the first time you hear it. And you will hear it again and again. You will never stop hearing it. Those horns have become a signifier, a calling card. Beyoncé has used those horns on two songs, "All Night" and the "Flawless" remix, and in her Coachella set. Lil Wayne used those horns as his backing on the first Dedication mixtape, when he was explaining why he called it Dedication. Those horns have floated lazily through Childish Gambino and Joey Bada$$ songs. They will keep coming back to us, again and again. They will never go away.

Because it's not just the horns. The horns sound great, of course. The riff they're playing is long enough that you can chop it up, make tons of little riffs out of it. You can do a lot with that sound. But it's not just the sound. It's the sound's context. When we first heard those horns, OutKast were an acclaimed and successful Southern rap group -- a group that, if you were paying attention, had already released two classic albums. They'd pushed themselves and tested their audience. They'd done things. But they hadn't really done anything to prepare us for those horns, or for the song that those horns call home.

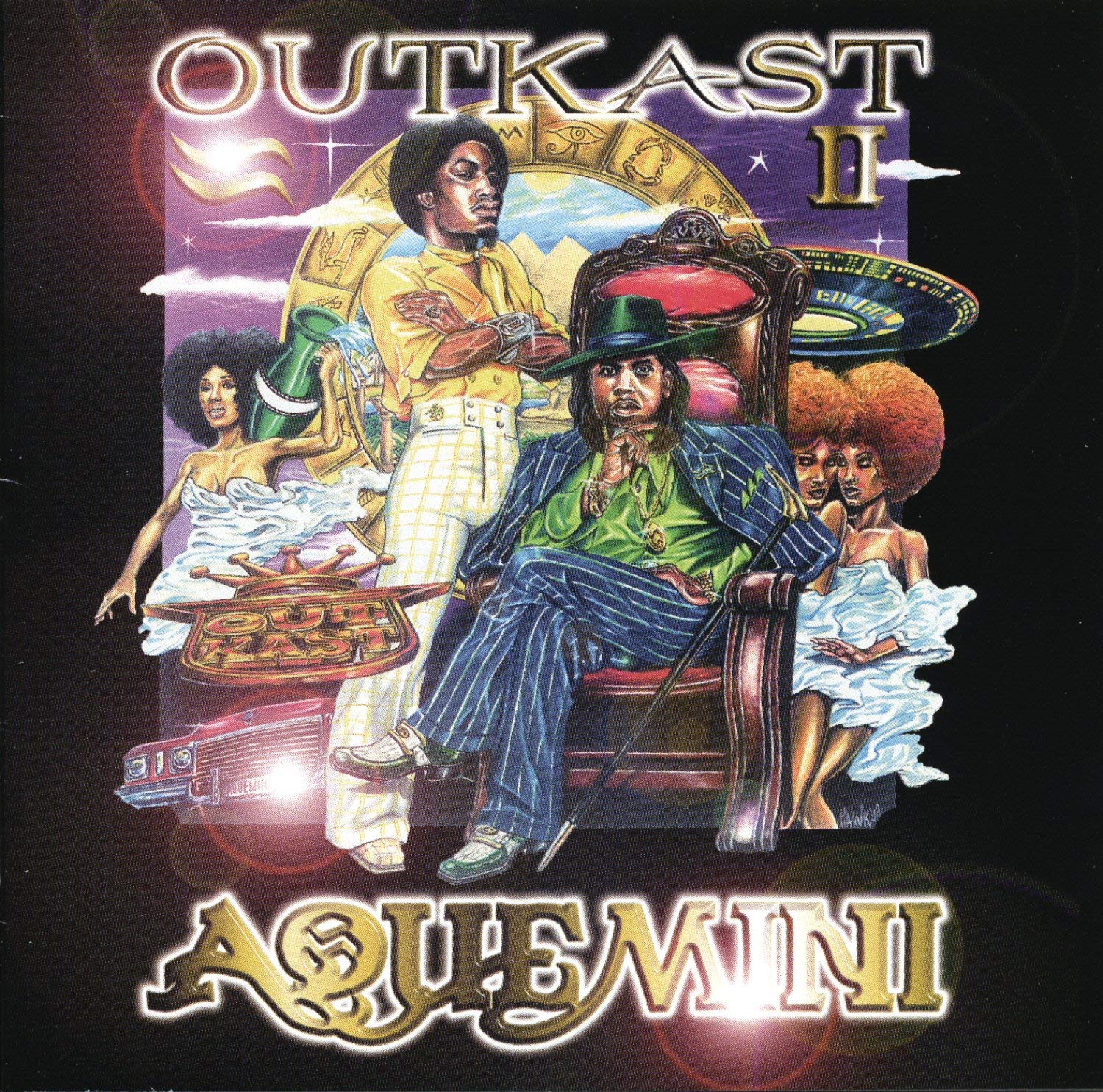

Those horns come from "SpottieOttieDopaliscious," a song from near the end of Aquemini, OutKast's third and best album, which turns 20 tomorrow. "SpottieOttie" isn't a rap song. There's no rapping on it. Instead, there's just talking. On that song, André 3000 and Big Boi reflect on the existence of an old Southwest Atlanta roller-disco, on the sorts of things that might happen there. André lays out the scene: The sounds, the smells, the possibilities, the fights that might suddenly break out deep into the night. He's never actually been there, and he's not scared to admit it. (The one time he made it to the parking lot, he was too drunk to get through the door.)

Big Boi meditates on the ways a night at that club might change your life. Maybe you'd meet someone. Maybe you'd fall in love, or at least lust. Maybe, four years later, that night would lead a new life into this world. And maybe that would lead to you sitting at home, wondering how you'd scrape up enough money to keep that new life alive. (Big Boi's turn on that song is the first time I can remember hearing anyone using the word "trap" the way we now understand it, 20 years later.)

While André and Big Boi get lost in their memories and fantasies, the music underneath them ripples and undulates for a full seven minutes. Sleepy Brown squeaks out an absolutely lovely scene-setting verse. Bongo drums rattle eloquently. A deep and heady reggae-style bassline slowly unfurls itself. A guitar murmurs out the riff from Genesis' 1973 prog excursion "Dancing With The Moonlight Night." And then there are those horns. It's almost too beautiful to exist.

So how could it exist? How could a commercially successful rap group, deep into rap's first gilded age, make something that warm and layered and imagistic and thoughtful? How could they make something with no rapping on it? It took time, and it took work. Long story short: OutKast had made two successful albums, so they had faith from their label. That gave them artistic control, and it also gave them the kind of budget that only existed in the late '90s. And so they were able to take their time and experiment. They were given the space and the means to truly find their sound, and what they found was magical.

André wanted to produce, and he wanted to get into live instrumentation, so that's what he did. Along with a crew of musicians, OutKast spent months on Aquemini, basically living and breathing the album. They were able to do things like the 3AM jam session that led to the nine-minute astral funk excursion "Liberation," a song that might be even more radical than "SpottieOttieDopaliscious." An A-list rap album with a song built from a late-night live-musician jam session would be unthinkable now. In 1998, it was fully and completely alien. And it led to the moment when Erykah Badu, André's baby's mother, broke in with so much beauty and gravity in her voice that I pretty much had to renegotiate my feelings about neo-soul on the spot.

By all accounts, the Aquemini sessions were a family affair all the way down. André got his old babysitter to sing backup on one song. His stepfather, a reverend, played harmonica on "Rosa Parks." (Again: A club-friendly rap single with a harmonica break. Not a done thing.) André's infant son Seven fusses in the background on "Slump." In the great Creative Loafing oral history of the Aquemini sessions, here's how LaFace records A&R Kawan Prather explains the decision to use Badu on "Liberation": "Dre's baby mama was Erykah Badu. I mean, damn, why wouldn't you put your baby mama on the record if she's Erykah Badu? It's not like he came to the studio and said, 'I want to put my girl on the song,' and this bitch work at the Varsity. She's Erykah Badu. OK, do it."

And even Raekwon's appearance on the jumped-up single "Skew It On The Bar-B" was a beautifully random occurrence. Rae was the first non-Dungeon Family guest rapper ever to appear on an OutKast song, and you might think that verse was the result of some kind of record-label negotiation, an attempt to get OutKast records played on New York radio. But it wasn't that. Big Boi ran into Raekwon at Atlanta's Lenox Square Mall, and they took a liking to each other. Big Boi and Raekwon recorded their verses in the studio booth together, firing each other up. I've never heard it, but apparently if you listen closely enough, you can hear bottles clinking against chains, deep in the mix.

André has said that he wanted to get Vincent Price on the nervously mystical sci-fi song "Synthesizer," which would've been amazing. But André hadn't realized that Price had died three years earlier. Instead of calling up Christopher Lee or somebody, he got funk godfather George Clinton, who intoned absurdities about "she'd dance on your laptop while your laptop's on your lap." And that somehow turned out great, too. Some albums are just charmed that way.

Clinton's appearance made sense because the sound of Aquemini was so clearly descended from the music he'd made with Funkadelic. Clinton's music, especially his music with Parliament, was maybe the most popular sample source all through the '90s; it's the backbone of The Chronic, for one. But OutKast weren't interested in sampling Clinton. Instead, they took off running with the sensibility that he'd shown on records like Maggot Brain. And that sound doesn't just come from George Clinton. André was listening to a whole lot of Bob Marley during the sessions, and he incorporates that sound, too. But he doesn't take that sound in obvious ways, like a Wyclef Jean might. (A couple of years before, Jean had had an alt-rock radio hit with what was basically just an acoustic dorm-room cover of "No Woman No Cry.") Instead, André found the sense of space in those Marley records, the feeling of those sounds instinctively pushing up against each other.

It's a dark, heady, downbeat sound, full of instrumental flourishes and weird noises bubbling up from deep in the mix. It's heavy and portentous, and it happily wallows in emotional turmoil. The sound works for heavy, thoughtful sprawls like "SpottieOttie" and "Liberation." It works for left-field flare-ups, like the righteously deep rock-guitar riffing on "Chonkyfire." But it also works for lithe, upbeat singles like "Rosa Parks" and "Skew It On The Bar-B." You can build a whole world out of that sound, and that's what OutKast did.

André had spent the years before Aquemini getting weird, speaking and rapping in cosmic turns and wearing the silliest outfits that he could put together. He knew he was pushing into deep and risky territory with the album, and that's why it was such a smart move to kick off Aquemini with "Return Of The G," the song where André acknowledges all the shit that people were saying about him and calmly slaps it all down: "What's up with André? Is he in a cult? Is he on drugs? Is he gay? When y'all gon' break up? When y'all gon' wake up?" (The answers to those first five questions, respectively: Too much to summarize, no, no, no, and as soon as filming wrapped on Idlewild. The final question was based on false assumptions, so it has no answer.)

"Return Of The G" also lays out the whole OutKast story and dynamic in ways that put the rest of Aquemini into context. Even a new fan like me, a guy who was only glancingly familiar with OutKast before Aquemini, could hear that song and figure out everything that was going on with them. Here we had André, who had come in as a shit-talking teenager and who had transformed himself into a space warrior while growing up in the public eye. He wanted to talk about time traveling, rhyme javelin, something mind unraveling. He was a star, but he’d decided that he’d rather by a comet by far, rrrrah.

But we also had Big Boi, who hadn't followed André down all those rabbit holes but who stood by him just the same: "We brothers from another mother, kinda like Mel Gibson and Danny Glover." Big Boi is a weirdo in his own quiet ways, something that his late-career solo records have made clear. (Big Boi also wanted to start the album with the Goodie Mob collab "Y'all Scared," and he and André reportedly got into some serious fights about it.)But Big Boi was the anchor in the group, the one that kept André connected to his own roots even as he spiraled outward. That push-pull dynamic made for some incredible rap music.

Maybe André needed that pressure to remain rap-relevant even as he willed himself further and further away from the center. Maybe that tension was an animating force. Whatever the case, the things that André did on Aquemini were simply astonishing. I'd never heard a rapper do the things that André did on Aquemini. I've still never heard it. It's one of the all-time great single-album performances in rap history.

André's rapping on Aquemini is technically dazzling -- all these different fast-rap flows that still come off reflective and conversational. He could talk shit when he wanted; we know that from the previous two OutKast albums. But he almost entirely held himself back from talking shit on Aquemini, even when he probably should've basked in his own glory. His verse on "Rosa Parks," for instance, is about a heavy conversation with a fortune teller, and not one single person would mind if it was just about how cool he is. Instead, André saved the shit-talk for the skits that he wrote, about the strawman fan who'd gotten too weirded out for OutKast and who'd switched his allegiance to the fictional generic rap group Pimp Trick Gangsta Clique. (At one point, André was going to get together with Cee-Lo and Sleepy Brown to make a Pimp Trick Gangsta Clique record, and it's a genuine tragedy that this never happened.)

But the André of Aquemini isn't even all that interested in the state of rap music, even though he remains world-historically good at rapping. Instead, he's deep in the stoner-philosopher zone. He gets all Radiohead, worrying about the impact of fast-advancing technology on our developing brains. He wonders about his own longevity in a peacefully detached sort of way. He imagines what it would be like if the world was ending and he and his friends just had to get to their Dungeon homebase one last time. He tells the story of an old grade-school crush who died of an overdose. He gets mad about the impact of crack on America's disenfranchised communities. Not all of his lines hold up to scrutiny; witness the "Mamacita" verse where he seems to violently freak out about the idea of an ex coming out of the closet. But all of André's work on the album shows a curious, feverish, restless mind who knows how to translate all his most far-out impulses into compelling music.

I've been rhapsodizing about André for this whole piece, and that runs the risk of casting Big Boi as a mere supporting player. But that's not what he was. Big Boi, like André, as an absolutely elite rapper, a frisky motormouth with an otherworldly rhythmic command and a playful sense of how to put words together. Plenty of Big Boi's lines from Aquemini remain relentlessly quotable: "Pay your fuckin' beeper bill, bitch." He goes solo on "West Savannah," a first-album-era relic that OutKast repurposed for the new album, helping ground all André's cosmic talk with a warm and thoughtful hometown reminisce. And perhaps most importantly, Big Boi wrote most of the album's hooks. Those hooks, sharp and focused earworms, are endlessly important to the album's replayability. They're what turns what might've been an interesting left turn into a straight-up classic.

I spent much of the winter of 1998, my first season away at college in the frozen landscape of Syracuse, deep in the Aquemini zone, trying to wrap my brain around the enormity of the album's accomplishment. Heard on cassette, the best way to hear Aquemini, it played out as a classical two-sided album statement, a personal internal headphones journey. It presented Atlanta as a place full of inconceivable levels of talent, and rap as something deep and spacious and unrestricted and connected to the sort of exploratory impulses that my classes weren't quite giving me. Aquemini just blew my whole shit apart. I didn't have any idea that an album could do the things that it did. It remains my favorite rap album of all time. It might be my straight-up favorite album of all time, without genre qualifiers. (My stock answer to the favorite-album question has always been Fugazi's Repeater, and I'm almost afraid to listen to Aquemini and Repeater back-to-back.)

Aquemini changed things, and not just for me. It pushed OutKast into a whole new stratosphere. They were platinum within two months, double platinum within 10. They were all over MTV in ways that they never had been before. They were on tour with Lauryn Hill, someone who was exploring similar feelings and ideas with similar levels of mass-culture resonance. They went through a protracted legal battle with the actual Rosa Parks, who wasn't thrilled about how they'd used her name. OutKast's singles didn't chart as high as their ATLiens singles, but the duo became crossover word-of-mouth sensations and critical favorites, even among the rock critics who hadn't given the first two albums the time of day.

One album later, OutKast would become a pop phenomenon, something that couldn't have happened if Aquemini hadn't laid the foundation. But the two more-successful albums that followed, great as they may be, are nowhere near as perfect as Aquemini. Aquemini stands as that rare moment where everyone involved is operating at peak capacity, where everything falls into place, and where the world changes because of it. The album ends with a crackly sample of André, at the 1995 Source Awards, letting a hostile New York crowd know that "the South got something to say." It's a great little victory-lap moment from someone who's usually too humble to bother himself with victory laps. And it was earned. After Aquemini, nobody could ever doubt that statement again.