One could argue -- particularly if "one" is "me" -- that the greatest album of the 21st century was released only about three weeks into it. I make this argument from nowhere resembling objectivity: On a January night 20 years ago tomorrow, I stood shivering outside of a Tower Records (R.I.P.) waiting for the opportunity to purchase D’Angelo's Voodoo at midnight, a particular music-consumer experience that, in 2020, I can say with near certainty that I'll never have again. I took it home and listened to it, and for what feels in hindsight like several years I barely ever stopped. Every young person who decides to write about music for a living tends to have one work that, more than any else, made them do it. Voodoo is mine.

Twenty years after its release Voodoo remains the greatest album-length synthesis of hip-hop and R&B ever made, as well as a work saddled with one of music's more fraught and complicated legacies. Voodoo sold 320,000 copies in its first week of release and debuted at #1, a startling feat for a dense and challenging work from an artist who'd released one previous studio LP that hadn't cracked the top 20 and was nearly five years old. (It's hard to believe, but five years actually once felt like a really long time to wait for a new D'Angelo album.) There are a number of reasons for this -- Virgin promoted the hell out of it; D's fans were cultishly devoted and ravenous for new stuff -- but the biggest was probably "Untitled (How Does It Feel?)," a song that had first appeared in October of 1999 as the B-side to "Left & Right" and had been officially released as a single on the auspicious date of January 1, 2000.

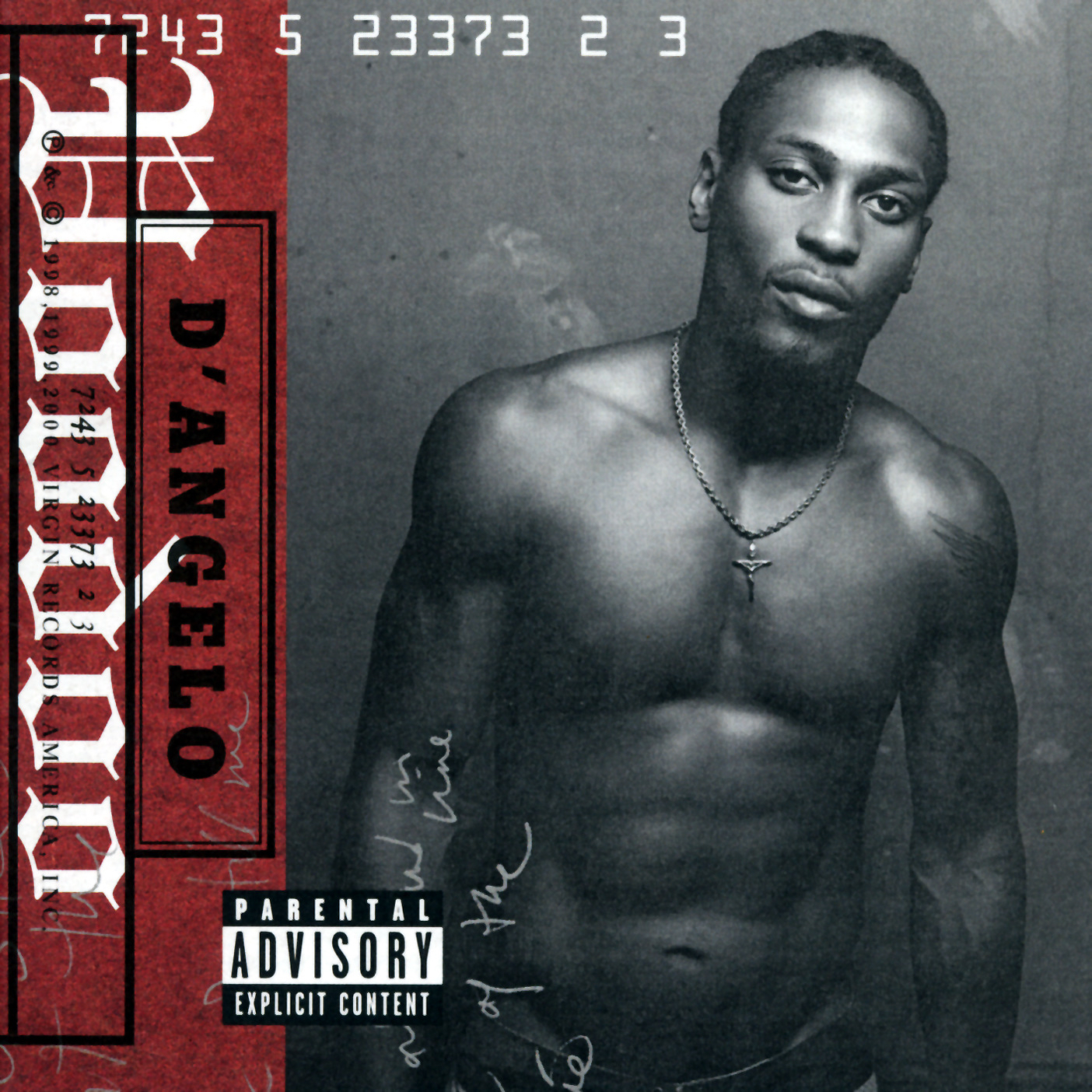

Before the album even arrived, "Untitled" seemed destined to become the defining track of Voodoo, and for a long time it was. The song hit #25 on the pop charts and #2 for R&B, but these numbers don't begin to do justice to its cultural impact, which can only be described in terms of That Video. Directed by Paul Hunter, the MTV version of "Untitled" consisted of a single, continuous shot of a remarkably chiseled, seemingly nude D'Angelo (in reality he was wearing low-slung pajama pants, kept carefully out of frame) singing into the camera, so convincingly pantomiming the song's slow build toward musical ecstasy that rumors swirled that he’d been receiving oral sex during the shoot. It was inarguably stunning and instantly iconic; in 2018, Billboard named it the third-greatest music video of the 21st Century.

It was also, in many ways, tragic, suddenly turning a famously shy artist into one of the most literally and figuratively overexposed figures in popular music. Like any act of sexual objectification, it was dehumanizing; live shows became infamous for fans screaming at D'Angelo to take his clothes off as soon as he took the stage. "One time I got mad when a female threw money at me onstage, and that made me feel fucked-up, and I threw the money back at her," D recalled to writer Amy Wallace in a 2012 comeback profile in GQ, one of the few extensive interviews he's sat for in the past two decades.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

Furthermore, D'Angelo’s physique did not naturally look like that -- no one's does -- and was the result of prolonged work with a personal trainer in the run-up to Voodoo's release. Touring life is unconducive to such regimens; Questlove recalled that D would sometimes postpone shows in order to frantically do stomach crunches. Delays and cancellations abounded, until D'Angelo retired from the road and public life for over a decade, turning a man who was briefly pop music's greatest sex symbol into its most mysterious and, at times, troubled recluse.

It's worth emphasizing here that "Untitled" is an incredible recording and performance, a slow-burning ballad that channels a tradition running from Ray Charles to James Brown to Al Green to Prince. Since his emergence as a prodigy out of Richmond in the mid 1990s, D'Angelo had been seen as one of the leading lights of the movement/subgenre dubbed "neo-soul," and for much of his early career, he didn't shy away from this. He was an obvious student of musical history, and his renown as a singer/songwriter/multi-instrumentalist invited obvious comparisons to Stevie Wonder and Prince. He'd covered Smokey Robinson's "Cruisin'" on his debut, Brown Sugar, and had taken on Marvin Gaye, Eddie Kendricks, Howard Tate, and Prince himself on various soundtrack albums and compilations. In early 2000, "Untitled" seemed to fit snugly within this lineage, provided you ignored its subtle hints of refusal: the false start; the cut-the-tape ending; the very title itself.

As anyone who bought Voodoo in January of 2000 can tell you, it took only a few moments into the album to realize that "Untitled" was far more outlier than forerunner. Voodoo has sometimes been described as the apotheosis of the neo-soul movement, a superlative that strikes me as entirely wrong. It was an utter break from that movement, a resignation letter that doubled as a prophecy. If neo-soul had been a back-to-roots movement that largely stemmed from the too-slick production and performance styles of much of mainstream 1990s R&B, Voodoo was something else entirely, the sound of an artist grabbing an entire, illustrious tradition of American music and declaring, "Now we're going here."

In fact, "Untitled" itself had been something of a false "beginning." Voodoo's actual first single, released well over a year before the album came out, was a far better indicator of what D'Angelo had in store, had anyone bothered to notice. First released on the soundtrack to Belly, the DJ Premier-produced "Devil's Pie" was a rattling and pummeling work of profane, gospel-inflected boom-bap, like Curtis Mayfield's "(Don't Worry) If There's Hell Below, We’re All Gonna Go" reimagined through an MPC powered by pure premillennial dread. "Fuck the slice, want the pie/ Why ask why, till we fry" were the song’s opening lyrics, half-spit, half-slurred by a multi-tracked D'Angelo, his voice split between registers, teetering on atonality.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

There had been nothing on Brown Sugar like this; the apocalyptic imagery, the sonic abrasiveness, Premier's signature cuts and scratches on the bridge. "Devil's Pie" was an audacious and completely extraordinary piece of music; it was also a flop. An almost violent departure from his prior work that was buried on a soundtrack to a movie that bombed, promoting an allegedly forthcoming album that wouldn’t arrive for 15 more months, the song evaporated into the void until it resurfaced as Voodoo's second track.

Still, in retrospect "Devil's Pie," much more than "Untitled," was the harbinger of Voodoo. The album opens with the ambient and foggy murmurings of a crowd, recalling the beginnings of soul classics like "We're A Winner" and "What’s Going On" but augmented by the sound of a drum, distinctly ritual in character. As musicologist Loren Kajikawa notes, the sound connotes the album's title, "suggesting that some mystical power is being invoked, a power that will be made manifest as the introduction gives way to D'Angelo and his band." After about 15 seconds these mysterious, beguiling sounds -- which will recur periodically throughout the album -- bleed into Voodoo's first track, "Playa Playa." The song begins in spare and atmospheric fashion, as a slowly repeating, three-note riff is increasingly augmented by light drums, finger snaps, backwards cymbals, bass, ever-growing layers of vocal, guitar, keys.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

The opening minute or so of "Playa Playa" is a rhythmic mission statement for the rest of the album to follow: flamboyantly unhurried, irrefutably funky but also distinctly off-kilter, the constituent parts never completely lining up and instead creating an ever-creeping, hypnotic soundscape of uneven strokes, microscopic archipelagos of sound and space bound by slink and slippage. For a group of people to play like this, at this tempo, for any prolonged period of time is almost impossibly difficult, and requires a virtuosity that both entails and exceeds the mastery of practice and technique and history. Musicians -- particularly those who ply their trade in rhythm sections -- often speak in vaguely mystical tones of the concept of "feel," a word that collapses the individual and group into a particular sort of sensual experience that underlies (in my opinion, at least) music-making in its highest form, and R&B music in particular.

This particular feel that we hear at the outset (and throughout) "Playa Playa" -- which, despite the paragraph above, is entirely indescribable, but you absolutely know it as soon as you hear it -- is the defining sound of Voodoo, heard on tracks like "The Line," "One Mo 'Gin," "The Root," "Greatdayindamornin'," and elsewhere. The musical brain trust around Voodoo was a loosely-knit collective known as the Soulquarians. Founded by Questlove, D’Angelo, keyboardist James Poyser, and hip-hop production maestro J Dilla, the Soulquarians soon included Welsh bassist Pino Palladino and jazz trumpeter Roy Hargrove. Throw in guitar virtuoso Charlie Hunter on several tracks and Voodoo featured some of the best players of their generation doing some of the finest work of their careers.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

And yet the skeleton key to Voodoo’s rhythmic magic is Dilla, whose influence over the album is massive even if he's never credited as a producer. In his great book Playing Changes, Nate Chinen writes that “[e]ach of the principal musicians on Voodoo traces this revolution in rhythm back to J Dilla." Questlove in particular has repeatedly invoked Dilla, telling writer Jason King, "The thing that really attracted me to D'Angelo’s music was this inebriated execution thing that he had, which we both got from J Dilla." Dilla, who passed away in 2006, was one of the great musical geniuses of hip-hop, a producer whose brilliant ear for sampling coupled with his stubborn refusal to use quantization -- a tool that allows beatmakers to snap their sounds into "proper" rhythmic place at the push of a button -- led to one of the most unique and influential sensibilities in modern music, forging digital worlds that were nonetheless shot through with tactile intimacy and idiosyncratic humanity.

The sound of Voodoo is the sound of some of the world's finest instrumentalists setting out to replicate the sound of deliberate glitch and willful technological misuse, a virtuoso rhythm section in Questlove and Palladino whose point of spiritual departure was a sample-based musician who programmed like a percussionist in some altered state. (In a 2013 Red Bull Music Academy interview, Questlove recalled hearing Dilla for the first time as "the most life-changing moment I ever had… It sounded like the kick drum was played by a drunk three-year-old.") That sound is, in many ways, the collision of the two centuries, an intoxicating mobius strip of analog into digital into analog, human into machine and back, round and round and back again.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"][/videoembed]

And then of course there were the songs themselves. Voodoo found D'Angelo largely eschewing the more conventional compositional forms of Brown Sugar -- an album awash in hooks and refrains -- for a more incantatory, at times almost stream-of-consciousness approach to songcraft. Densely layered vocals floated dreamily in the mix, delivering lyrics both acerbic and aphoristic. "Will I hang or get left hangin’?/ Will I fall off, or is it bangin’?" he wonders on the churning, dream-like "The Line." Or consider the first verse of "Africa," the album’s last track, with its cutting remark of "I dwell within a land that’s meant/ Meant for many men not my tone," and the dual meaning on "tone," skin and sound. While hardly a wordy album, the singing and songwriting on Voodoo emphasized flow, atmosphere, and a sort of churning, rhythmic relentlessness; one of the reasons that a track like "Devil's Pie" worked so well was that D'Angelo was writing like a rapper, albeit one with one of the finest singing voices of his generation and steeped in the whole history of American rhythm and blues music.

By the turn of the millennium there had already been countless attempts to bridge the traditions of hip-hop and R&B, many of which had been successful -- less than a year before Voodoo's release Lauryn Hill took home five Grammys for The Miseducation Of Lauryn Hill. But no album synthesized the two forms as fully and provocatively as Voodoo. Rather than, say, using an R&B singer to augment a hip-hop track or occasional rap verses to fill out an R&B record, Voodoo was a work that somehow lived in both at once, pulling two enormous musical traditions into concert with each other like nothing had before. Back in 2000, when no one knew that D'Angelo wouldn’t make another album for 14 years, Voodoo sounded like nothing less than the future. Twenty years later it sounds like something even more special than that.