The songwriting legend John Prine died last week. Even before Prine passed away, when the news came out that he was sick with coronavirus, Prine's peers and admirers were quick to sing his praises. Tons and tons of people -- from Roger Waters to Phoebe Bridgers to Natalie Maines -- have covered Prine's songs in recent days. It's a measure of how beloved Prine was among songwriters. Today, Elvis Costello, another beloved songwriter, has written at length about how much Prine's music and friendship have meant to him.

In a long Facebook post, Costello talks about growing up admiring Prine and actually learning to shake off his influence, since he knew he couldn't write the same kinds of songs: "I had to put aside the quiet songs that I had written in imitation of John Prine in order to raise and find my own voice." Costello also thoughtfully compares Prine to other songwriters like Randy Newman and frequent comparison point Bob Dylan. And he shares memories of spending time with Prine. Read the full text of Costello's post below.

I was speaking today to my pal and Best Man, the playwright Alan Bleasdale about the sad passing of John Prine. We recalled that forty years ago, when we were first introduced, the condition of us becoming friends was that the other also loved John Prine.

This was non-negotiable, although neither of us needed to negotiate about it. Alan told me that if he had been a songwriter instead of a playwright, he would have wanted to be John Prine. I told Alan that when I was nineteen and only pretending to be a songwriter, I too wanted to be John Prine.

Now it is well known that John worked as a mailman before breaking into music, in terms of matching his rare and unique gifts, I might as well have grabbed my sack of letters and hit the pavement as imagine that I could write like John.

Alan told me he first heard John when he was teaching on what was then called the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. How he managed to do so on a small atoll in Micronesia, is something that is lost to the mysteries of broadcasting history.

My own introduction was via an Atlantic Record single plucked out of a discount bin of 45rpm records on the counter of Rushworth and Dreaper in Liverpool.

It was a copy of “Sam Stone” backed by “Illegal Smile”, which in two short songs showed me everything that I would come to appreciate in John’s writing; on the A-side, a song of incredible empathy, an unflinching account of an addicted veteran and the impact of his torment on his family, all written with the authority of a man who had served in the army, while the b-side, was a good-humoured celebration of forbidden pleasures.

These two sides to John Prine’s writing and the characters in his songs put me in mind of another great favourite of mine, Randy Newman. While Randy Newman’s songs were often portraits of grotesques, rendered with the smallest but essential sliver of sympathy, Prine reached into similar darkness to pull out elusive light.

While Randy Newman’s complex harmony and piano compositions were nearly impossible to imitate on the guitar, a songwriting novice could mistake John Prine’s use of simple guitar accompaniment for something one might replicate. Nothing could be further from the truth.

If John Prine had only written his initial self-titled album, his place among America’s great songwriters would be secure. In addition to “Sam Stone” and “Illegal Smile”, one might add “Donald & Lydia”, “Hello In There” and “Paradise”, unique portraits of awkward lovers, shut-ins, older people or those crushed by the wheel of industry. These were songs that no one else was writing, filled with details that only Prine’s eye or ear caught; the arcane radio, the damaged and the destitute. The songs were filled with what sounded like sound advice from a friend in a crowded bar or a voice in the margins, but never one that was self-pitying or self-regarding.

Both, “Hello In There” and “Angel From Montgomery” traveled across musical styles to become pop hits for other artists at a time when unique songwriting voices ranging from Prine to Jimmy Webb to Randy Newman all enjoyed a broader audience for their songs that would be hard to imagine, just a few years later.

Every John Prine album since has delivered songs to his repertoire that no one else could possibly have written; “Sabu Visits The Twin Cities Alone”, “Unwed Fathers” and “Let’s Talk Dirty In Hawaiian” being just three utterly contrasting titles displaying a talent more akin to a 1930s short-story writer or humorist than a folk singer.

Styles change but there is no John Prine, “Disco Period”, no John Prine, “Prog Rock Concept Album”.

In my faulty memory of it, John’s first album was a “solo record,” there was, of course accompaniment but it is so discreet and perfectly weighted as to leave the singer perfectly framed.

As time went on some of the records reflected a sense of knowing what “got over” to an audience when performing with a band, John’s songs augmented by tunes by Merle Travis and Chuck Berry, the rock and roll of “Ubangi Stomp” along with songs made from The Carter Family and a Leon Payne song made famous by Hank Williams, “They’ll Never Take Her Love From Me".

A long while ago, I stumbled through a door in Wisconsin between two adjoining theatres, the one in which I was due to play the next night and the one in which John and his band were already in full flight.

In my dream of the show, there was a brass band playing and maybe an accordion or perhaps John simply summoned them up with his words. I remember he danced a little, very joyfully and that surprised me as I remembered the way I imagined him when I first listened to his records.

Perhaps he too was hunched over a guitar, trying to puzzle out how to pull beauty from so few chords or in need of an audience that allowed for the hushed dynamic of the songs. It was a wonderful surprise that he could also be the charming showman, possessed of some surprisingly nimble footwork.

This was confirmation of an important lesson.

I had to put aside the quiet songs that I had written in imitation of John Prine in order to raise and find my own voice. His gift was to be able to still an audience to the scale of his song; the painful tenderness with which he could sing anyone of his earliest songs as if they were brand new and then follow up with a “new” song, say “Jesus The Missing Years” or any of the tunes from “Fair & Square” or his latest Top Five hit album, “The Tree Of Forgiveness”, songs that were equal in quality, even when different in scale and ambition.

It’s odd now to recall that John Prine critics once pinned a sign on John that had plagued anyone with an unusual vocal delivery and a way with words, from Donovan and Arlo Guthrie before him, to Loudon Wainwright III and Bruce Springsteen after him. John Prine was supposedly “The New Dylan”, as if there was anything remotely malfunctioning about the old one.

It is odd to regard that comparison at this distance. I think it as unlikely that Bob Dylan could have written “Hello In There”, as it would be that John could have written “Masters Of War”, but they both had voices of the country, it’s experience and the price it paid.

There is sometimes a Western gunfighter to be found in a Bob Dylan lyric, the killer line delivered with the flourish of a revolver spun back into the holster. The songs can be grave, almost apocalyptic, tender then sly, upsetting and then funny. Prine’s lyrics seem only to overlap in these last three properties, there is a tight focus to the portraiture but with a humility and humanity that is his alone.

I feel each songwriter would have surely admired the other and have said so. There is no “new” or “better”. These are estimations made by people who will never write a song.

In September 2009, John was one of three songwriters featured on the television show, “Spectacle” of which I was the presenter and co-writer. By this time, we had established a method by which I would sing a few songs to welcome the audience to the theme of the evening with hope that one of them might serve as the musical introduction to the edited broadcast.

I opened that taping with “Poison Moon” and “Wave A White Flag”, two of the songs that I told the audience were written when the height of my ambition was to be able to write with the economy and unusual subject matter of a John Prine song.

One was a fatalistic tune about finding hope in the night sky that could not be sensed on the earth and another a little ragtime trick, framing a tale of violent love. Neither song made it onto my first record and neither song made it into the final show but I’d felt better about telling the Apollo audience how much John’s example had meant to me, even if the musical results didn’t amount to much.

John was the first interview subject, prefacing our conversation with a stupefying performance of his epic song, “Lake Marie”. Truthfully, I could have talked to John all evening about the implications and the writing of this one incredible, panoramic song but of course much of our conversation had to be put aside by the editor in order to accommodate the other guests.

Perhaps some future archivist may stumble upon the footage years from now and recognize it to be a chat between one of the great songwriters of the 20th and 21st Century, talking to a man in glasses with a clipboard.

After fine performances and conversations with Lyle Lovett and Ray LaMontagne, the natural order of things was restored as the quartet of singers performed the Townes Van Zandt song “Loretta” with Lyle and Ray taking the first two verses and John and I harmonizing on the third, before we all supported John on a rendition of “Angel From Montgomery”, which closed the show.

Prine songs sometimes seem like a frayed route map of the emotions and speaking of the distance between two hearts or two realities. They don’t point angry fingers, they let you make up your own mind.

When I consider the moment in which I am writing, I wish we could hear the song John might have written about an exhausted nurse quarantined in her own attic away from her three frightened children or an ode to the fruit picker who puts the strawberry on our Sunday tart or the delivery driver or shelf filler who makes sure there is food to purchase for someone to put on the family table, because these seem like scenarios or portraits that might be found in his catalogue.

People are quick to tell songwriters to lampoon hucksterism or even to sing its praises. Someone will want their favourite songwriter to loudly sound the alarm or ridicule the morbid 24-hour industry of panic. I find it hard to imagine John Prine would have stooped to write such songs in any crude or obvious way.

It is perhaps easier to imagine John writing about the child or wife sheltering from a father or a husband’s rage of frustration due to confinement or addiction, as these feel like characters both found in this hour of trial and within John’s existing songs and from this I take comfort.

John Prine never needed to get on a soapbox to write and speak in song about the inequities, cruelties and the loneliness of life. I think it was more in a spirit of hope that John joined Emmylou Harris, Nanci Griffith, Steve Earle and myself on “A Concert For A Landmine Free World” organized with the help of veteran and activist, Bobby Muller in 2002.

The tour, that opened in Belfast and closed in Oslo was just five shows long but featured all the artists sharing the stage at once and singing in turn. Sometimes Emmy and I would harmonize on a tune of mine or a number by Felice and Boudleaux Bryant. Nanci Griffith might sing John’s “The Speed Of The Sound Of Loneliness”, while John himself sang different songs from his catalogue every night, always casting a spell to which the others would have to respond. There was never a heavy hand to the way his voice or his songs connected to the objective of the tour.

It was all understood.

By the end of the run, Steve Earle was permitting me to play a guitar counterpoint on “Fort Worth Blues” and I had enlisted the entire company to sing the refrain of “God’s Comic” with gallows humour.

Each show ended with John Prine singing “Paradise”, as well it might.

After the show at the Hammersmith Apollo, I greeted my mother and a friend as they came backstage. Turning around to see John standing on the stairs, I introduced him to my Ma and then said, “John, this is my best pal and your biggest fan, Alan Bleasdale” and a circle of friendship and song was closed.

In 2016, John Prine, Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan were awarded the PEN New England Award For Lyrical Excellence, one of a series of overdue acknowledgments that came to John in recent years.

This was the third such shared, approximately, biannual award.

After the initial secret ballot yield a dead-heat selection of Chuck Berry and Leonard Cohen and the voting committee chairman, Paul Simon, declined to cast a deciding vote, it was agreed that perhaps a shared award better illustrated the contrasts of lyrical achievement.

Unlike a televised awards show, this event had nothing to do with record sales or fashionable trends. Still, it was the just opinion of a committee of individuals - songwriters, authors and poets - not an act of God or a Law of Physics.

Two years later the award was shared by Kris Kristofferson and Randy Newman, so when the voting panel convened for the third time, there was a formidable standard to maintain.

As absurd as it is to compare objects of beauty, each member of the committee made a case for a number of wonderful lyricists before a unanimous decision was made to give the award to the writing team of Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan and John Prine.

The event at the J.F.K. Library in Boston was attended by voting members, Rosanne Cash, Peter Wolf, the poet, Paul Muldoon, chairman, Bill Flanagan and myself, along with many other writers and musicians. The other members of the voting committee, Bono and the Poet Laureate, Natasha Trethewey and the author Salman Rushdie were unable to attend.

Academic members of the PEN writing community and other guests spoke while Sturgill Simpson and I sang in praise of these three wonderful lyricists. John Mellencamp spoke humbly about the inability to face contacting John during a period of serious ill-health through which Prine had struggled and prevailed.

Perhaps it was his resilience that makes accepting John’s passing more difficult. He had repeatedly shown such strength and courage in overcoming the challenges of illness. He was so loved by Fiona and his family and all of his friends, admirers and listeners that it was easy to believe that he would be returned to us; to laugh as he read all of those many quotations from his lyrics that acquaintances, strangers and his longest-lived pals have been sharing in these last days. They tell us that a world with John Prine in it has been much better than the poorer one in which we now dwell.

I am grateful to Fiona Prine for the welcome she extended to the writer Tom Piazza, songwriter, Joe Henry and myself, when we spent an irreplaceable evening with her and John, last September.

It was a delightful supper of laughter and stories, with songs cited and memories marked, closing only as the glass of a slowly smoldering vintage jukebox filled with smoke and John had to disconnect it and crack open a window, breaking the spell into a gentle goodnight.

If that sounds like something John might have made up, then I guess I may have finally learned my lesson.

My love and thoughts are with Fiona, Jody, Jack, Tommy and all of John’s family and friends at this very melancholy time.

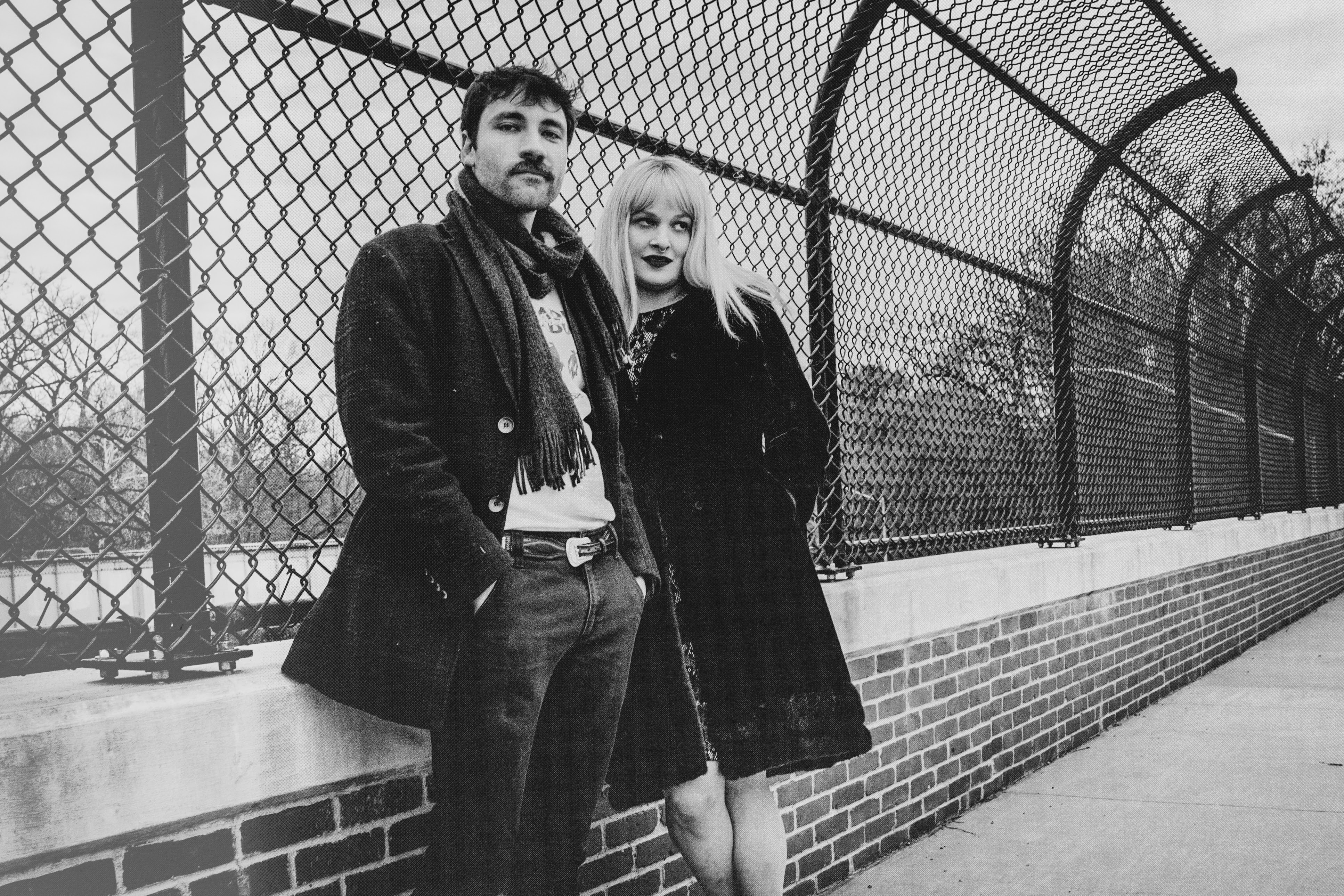

P.S. I should acknowledge my friend, John Hassan for letting me use this shot that he snapped at the reception following the 2016 PEN event.