Imagine if, instead of veering off into bleary electronics in the late '90s, R.E.M. went on to perfect the fuzzed-out sound they attempted on Monster. Imagine if, instead of blink-182's TRL-friendly juvenilia and the Warped Tour hijinks that followed, Y2K-era pop-punk had been altogether harder and smarter. Imagine if, instead of mutating into butt-rock, the post-grunge sound that ruled alternative radio in the late '90s had swerved back toward the killer hooks and crushing choruses of Nevermind. Imagine if you didn't even have to envision such superior timelines because some kids from Scotland brought them all to pass at once.

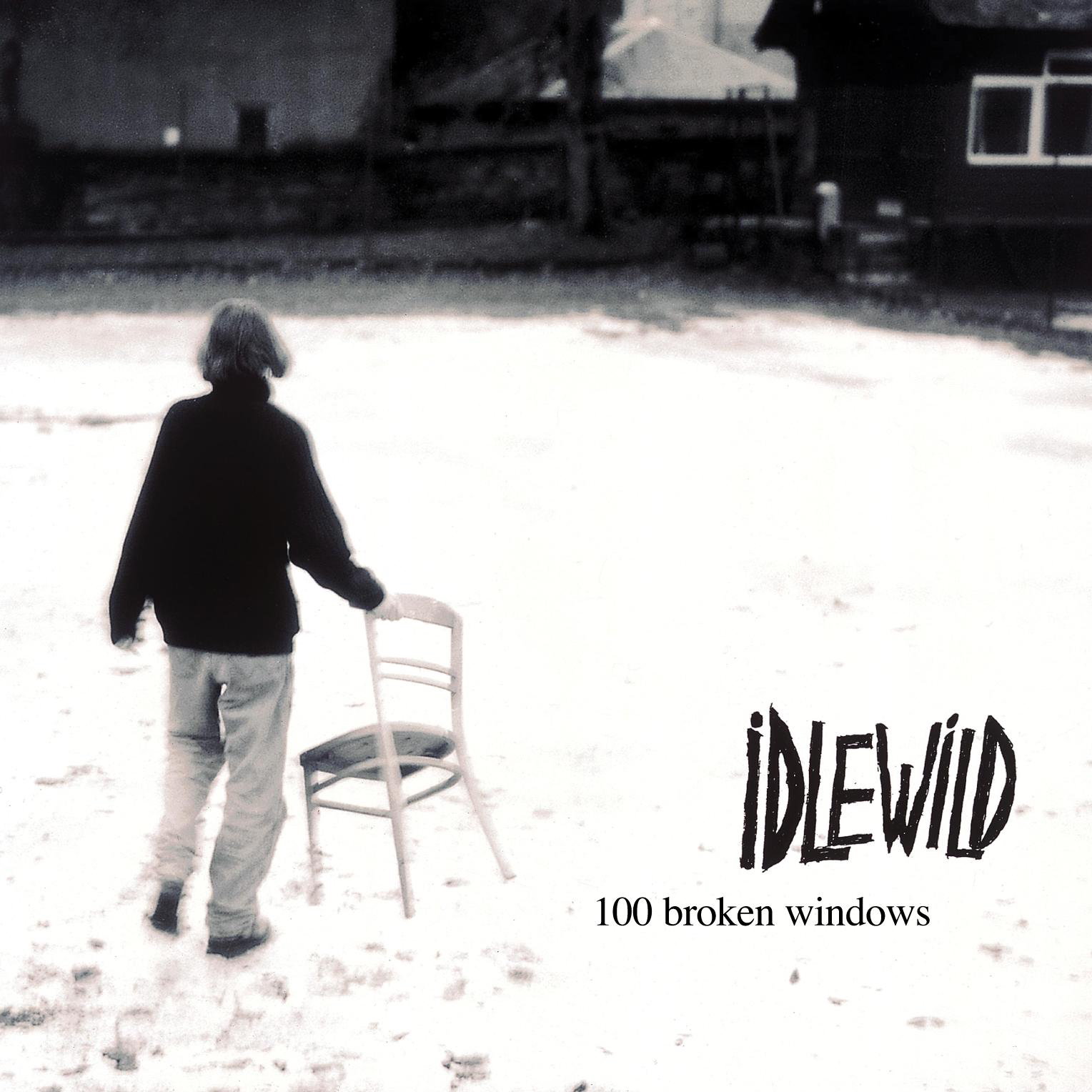

Twenty years ago this weekend, Idlewild released 100 Broken Windows in the United States. It rules. It's so good. Have you heard it? You need to hear it. Do you already know and love it? Treat yourself by listening again. Maybe if they'd had more expensive haircuts or a more intriguing narrative or whatever, Roddy Woomble and the gang would have been as big as the Strokes. Maybe their singer needed a flashier name than Roddy Woomble, which sounds like less like a rock star than a workmanlike midfielder who comes off the bench for Celtic.

Thanks to the rightful hype storm surrounding this album, they did become stars in Britain -- where the album had been out for a month by the time it arrived in the States -- and they're certified legends in their native Scotland. In 2009, readers of culture newspaper The Skinny even voted 100 Broken Windows Scotland's album of the decade above classics from Frightened Rabbit, Boards Of Canada, Franz Ferdinand, Primal Scream, Camera Obscura, and other heavy hitters. Meanwhile here in the US they had to settle for rave reviews, MTV2 rotation, and the undying love of a modest following.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=yMZR_JNvuU4[/videoembed]

Idlewild formed in Edinburgh in 1995 and quickly built buzz with their raucous live shows, a chaos documented on their scrappy 1998 debut Hope Is Important. Back then, NME famously compared them to "a flight of stairs falling down a flight of stairs" and "what Fugazi would sound like if they ate meat." Woomble's gifts for melody and poetic imagery were already on display -- Idlewild just often obscured them with breakneck tempos, snotty vocal delivery, and squalls of noise. The potential was clear, but the songwriting wasn't there yet. They hadn't mastered dynamics or figured out how to explore a range of styles while maintaining a coherent identity. Soon enough, though, they'd be soaring.

When they returned with 100 Broken Windows in 2000, critics were uniformly shocked by how much Idlewild had tamed their rangier impulses. "No more screeching," wrote Pitchfork. "No more punk-guitar chaos. No more uncomfortable strain." This wasn't entirely true -- "Idea Track," anyone? -- but there might have been a lot more of all that had the band stuck with Shellac's Bob Weston, who tracked the initial sessions for the album before Dave Eringa came into the picture. Idlewild's new material did not lend itself to the Weston-Albini school of visceral minimalism the way their earliest work had. Like U2 in the early '80s, these punks were now writing compact anthems that demanded a certain level of polish and grace. They needed to maintain their gritty immediacy while also sounding shot through with a larger-than-life grandeur.

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=Lg0mehFTr0I[/videoembed]

Speaking to The Skinny years later, Woomble reflected, "100 Broken Windows was very much, for me, us still getting somewhere, still finding our feet. I suppose that’s maybe the best era of any band, when they’ve gone beyond their debut but they haven't quite got to the peak of their popularity yet; where they’re somewhere in between. It's quite a pure area isn't it?" In Idlewild's case it resulted in a fleet of near-flawless pop-rock songs that sped along like sturdy sedans with surprisingly powerful motors, their sparkling paint jobs speckled with bits of sludge.

These nifty little machines became vehicles for Woomble's evocative turns of phrase, opaque poetry blown out into sing-along hooks in that grand alternative rock tradition. "I started becoming interested in using the microphone like a Super-8 camera to capture little snippets of things," he told The Skinny. "I knew I was never going to be like Leonard Cohen, but I had my own observations." These observations were always vivid, if sometimes inscrutable. What did it mean that Woomble needed "A Little Discourage"? Was "These Wooden Ideas" critiquing postmodernism or celebrating it? Exactly what stance was "Roseability" taking on Gertrude Stein?

[videoembed size="full_width" alignment="center"]https://youtube.com/watch?v=0U573b653Sg[/videoembed]

Parsing the meaning of these songs sometimes required deep thought, but enjoying them required no effort at all. Idlewild were flexing a newly discovered verse-chorus-verse mastery, song after song seizing listeners' attention early on and building momentum to an explosively catchy refrain. Snapping, jangling guitar riffs combusted into power chord infernos. The drums boomed and thwacked with such force you could feel it in your chest. Woomble could still shred his throat when the situation called for it, but his nasally hooks were becoming strong enough to turn lines like "Why can't you be more cynical?" into life-affirming refrains. These were not voice-of-a-generation landmarks, at least not here in America. But they were the kind of infectious guitar bangers that stick with you for life, and they added up to one of those underrated gems that become part of a person's private canon.

They don't make 'em like this anymore -- neither the universal "they" nor Idlewild themselves. The band progressed further into radio-friendly compression on 2002's good-not-great The Remote Part, a more commercially successful effort that has since become overshadowed by the legend of 100 Broken Windows. They've continued to kick out quality rock music ever since, but never have they sounded as inspired as they did at the turn of the millennium. On "Roseability" -- the album's best song, an alt-rock masterpiece worthy of all the hyperbole in the world -- Woomble suggests that paging through "scrapbooks and photograph albums" is a useless exercise, that you can't learn anything useful by looking backwards. It's a disputable thesis, particularly when digging through the past leads you back to an album like this one.