In The Number Ones, I'm reviewing every single #1 single in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, starting with the chart's beginning, in 1958, and working my way up into the present.

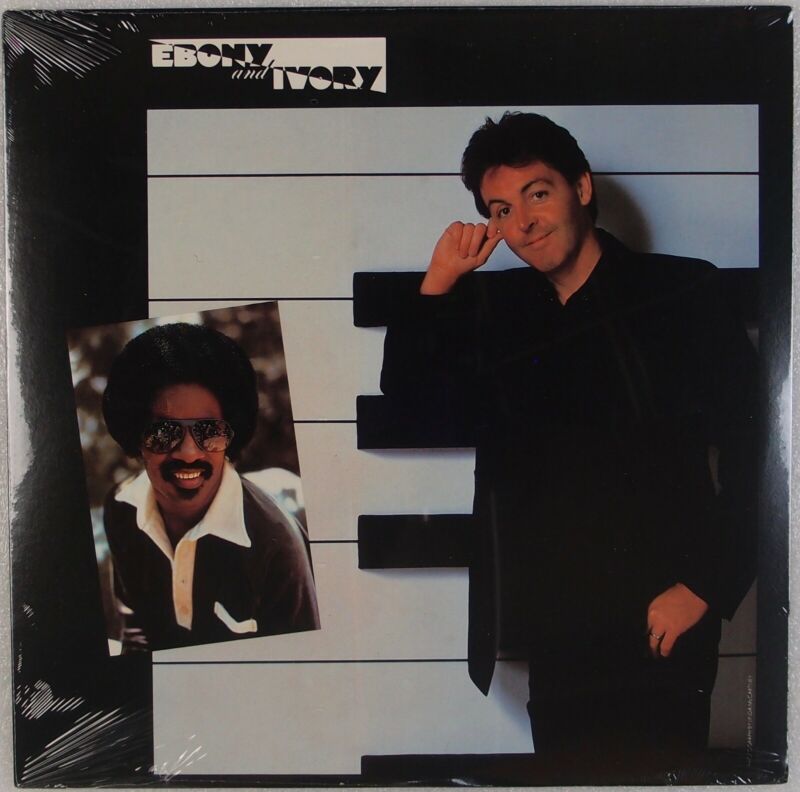

Paul McCartney & Stevie Wonder - "Ebony And Ivory"

HIT #1: May 15, 1982

STAYED AT #1: 7 weeks

"When I wrote the song, I thought, 'Maybe we don't need to keep talking about black and white. Maybe the problem is solved... Maybe I've missed the boat. Maybe it should've been written in the '60s, this song.' But I after I'd written it and recorded it, you look around, and, you know, there's still tension." That's a very astute decades-old observation from Sir Paul McCartney, the man who attempted to heal racial tensions in the most trite, simplistic manner imaginable.

The central metaphor of McCartney's song "Ebony And Ivory" is so basic that it doesn't really bear explaining, though McCartney still explains it all over again anytime anyone asks him about the song. McCartney had just been through a few personal upheavals. His band Wings had officially broken up in 1981, when Denny Laine, the only longtime member of the band who did not have the word "McCartney" in his name, quit the group. And of course, McCartney was also mourning the death of his former bandmate John Lennon. He was also, at least in some sense, playing catchup. There's some possibility that "Ebony And Ivory" is McCartney, long considered the glibbest of the Beatles, doing his best to inject some level of profundity into his solo work.

When McCartney first wrote "Ebony And Ivory," he'd just gotten into a fight with his wife Linda, and he was thinking that they should be getting along better. Without working particularly hard on it, McCartney stretched his analogy to encompass conflicts between black and white people -- a problem that, he thought, had maybe been solved. Maybe that general overall cluelessness is why "Ebony And Ivory" is so blasé and tossed-off, why it's utterly lacking in anything resembling urgency.

Talking to Bryant Gumble on Today in 1982, McCartney said, "I wanted to sing it with a black guy." The first black guy who came to mind was Stevie Wonder, the man who'd recorded what many consider to be the best Beatles cover ever recorded. (Wonder's 1971 version of "We Can Work It Out" peaked at #13.) Wonder was happy to do it. Talking to Dick Clark shortly after the song came out, Wonder said, "I won’t say [the song] demanded of people to reflect upon it, but it politely asks the people to reflect upon life in using the terms of music... this melting pot of many different people." Right now, all around us, we can see how well that approach works.

This is the central problem with "Ebony And Ivory," the reason that it's aged so poorly. Racial division is not the kind of thing that can be solved through amiable adult contemporary music. It can't be solved through angry brick-thrower music, either, but at least angry brick-thrower music seems to give more of a shit about the problem. In "Ebony And Ivory," there's no acknowledgment that the balance of power might be fucked up, that racial divisions are the result of historical crimes and atrocities. It's just: "Ebony and ivory live together in perfect harmony/ Side by side on my piano keyboard/ Oh lord, why don't we?" McCartney asks the question, and I don't know if he's interested in the answer. A rich and aristocratic pop star posing this question in 1982 has the same kind of energy as a major corporation putting up a vague racial-solidarity tweet amidst police riots today.

McCartney and Wonder recorded the song together on Montserrat, in the West Indies, with both of them playing a bunch of different instruments. McCartney played bass and guitar. Wonder played drums. Both of them played pianos, synths, and percussion. Linda McCartney and Denny Laine sang backup, and so did 10cc's Eric Stewart, a man who's previously appeared in this column as a member of Wayne Fontana & The Mindbenders. (I've seen some reports that Isaac Hayes also sang backup on "Ebony And Ivory," but I can't find confirmation of that anywhere reliable, and I sure don't hear him.) The Chieftains' Paddy Moloney played pipes. George Martin, McCartney's old Beatles collaborator, produced the track. While McCartney and Wonder were recording together in Montserrat, they also came up with a much better song that also appeared on McCartney's Tug Of War album: "What's That You're Doing?," perhaps the nastiest soul/funk track ever released under McCartney's name.

Musically, "Ebony And Ivory" lilts aimlessly. It's got a fairly strong central melody, but that melody unfolds with a self-satisfied indolence. Wonder's voice fits nicely with McCartney's; they do sing together in pretty good harmony. I'm not particularly mad at the lite-funk things going on during the breakdown. McCartney's bass gets busy in the same understated way that it often did in the Beatles. But that doesn't erase the sugary smugness of McCartney's lyrics and delivery. The song just never works hard to sell its feeble hypothesis. McCartney doesn't even bother to come up with a second verse; he just gets Wonder to sing the first verse again.

It's hard to imagine "Ebony And Ivory" ever convincing anyone to reconsider their deeply-held prejudices. Instead, it's the sort of song that flatters the listener -- that allows us to congratulate ourselves on our own enlightenment. Maybe that's why it was so popular. The song was also, I guess, a chance to hear two generationally beloved musicians singing together. "Ebony And Ivory" came out during an era of big blockbuster event-style duets. It arrived less than a year after "Endless Love," and it did the same kind of outsized, absurd levels of business.

Before "Ebony And Ivory," McCartney and Wonder were both doing fine for themselves. McCartney had hit #1 two years earlier with "Coming Up." Wonder hadn't been to the summit since "Sir Duke" five years earlier, and he'd taken some time off after his absurd run of '70s masterpieces. But he was steadily jamming out hits; just a few weeks earlier, he'd made it up to #4 with "That Girl." ("That Girl" is a 7.)

"Ebony And Ivory" was one of the biggest hits of 1982. Its doofy-ass music video got heavy MTV play even though Wonder and McCartney had to tape their parts separately. (It bugs me that shrunken McCartney is so light that the piano keys stay motionless when he walks on them.) With its seven weeks at #1, "Ebony And Ivory" is technically the biggest hit of McCartney's post-Beatles career, and it's the biggest hit that Wonder has ever had. "Ebony And Ivory" is also the only McCartney song that ever hit #1 on Billboard's R&B chart. Both McCartney and Wonder kept their streaks going after the song finished its run. They'll both be back in this column before long.

GRADE: 3/10

BONUS BEATS: Here's a bit of the 1982 Saturday Night Live sketch where Eddie Murphy's Stevie Wonder and Joe Piscopo's Frank Sinatra sing their own version of "Ebony And Ivory":

(You can watch that full, non-embeddable sketch here. Eddie Murphy's highest-charting single is "Party All The Time," which peaked at #2 in 1985. It's a 6.)

BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the scene from a 1983 Diff'rent Strokes episode where Dana Plato, Todd Bridges, and Janet Jackson sing "Ebony And Ivory":

(Janet Jackson will eventually appear in this column.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's KRS-One interpolating "Ebony And Ivory" on the 1990 Boogie Down Productions track "100 Guns":

(KRS-One has never had a top-10 hit. His highest-charting single, 1995's "MC's Act Like They Don't Know," peaked at #57. Ja Rule interpolated the hook from "100 Guns" on his 2004 Fat Joe/Jadakiss collab "New York," which peaked at #27.)

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's the "Ebony And Ivory" cover that the New York hardcore band Murphy's Law released in 1991:

BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BONUS BEATS: Here's Eddie Griffin and Denise Richards singing "Ebony And Ivory" together in the 2002 film Undercover Brother:

THE 10S: Willie Nelson's heart-crushed ballad "Always On My Mind" peaked at #5 behind "Ebony And Ivory." (Nelson's version wasn't the first. B. J. Thomas had recorded the first version of "Always On My Mind" in 1970, and Brenda Lee had released the first version in 1972. A 1972 Elvis Presley version had peaked at #20. A different version of the song would later peak even higher than Nelson's take.) Nelson's version is a 10.

Also, Joan Jett And The Blackhearts' sighing, sneering punk-rock prom-ballad cover of "Crimson And Clover," a 1969 #1 hit for Tommy James And The Shondells, peaked at #7 behind "Ebony And Ivory." It's another 10.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=xTfHhNg1iII