Before Rihanna had red hair, she had pink chains. In the video for her 2008 hit single "Disturbia," she's in a cramped space, pulling at her colorful bondage. The song was written by her then-boyfriend Chris Brown. Although it was theatrical and freaky, it presented her bound by demons, not fully free to be herself. This was before the gruesome Rated R and the painful period it reflected, the highly publicized aftermath of Brown's physical abuse. But "Disturbia" is a significant reminder that Rih posited a playful salaciousness even before she sang about being a masochist 10 years ago.

When Rihanna dyed her hair fire hydrant red in 2010, she said she felt liberated. It was the perfect bold look to accompany her fifth album in five years, an expression of sex-positivity and power with the quite-literal title Loud, released 10 years ago today. The color choice felt even more jarring than her previous haircut — a gunpowder black pixie cut and a luscious swoop of side bang that went well with a bubblegum pink military tank. "It seemed aggressive, but it was more defensive," she said of her gothic drill sergeant vibe. "It was like putting up a guard wall, this tough image that people couldn't get past, to me." Her Rated R-era hair was a shield that covered up what might be seen as weakness, reclaiming her vulnerability when she had no control over how much people perceived her. Following an album that wore every shade of black, it was a thrill to see her in the redemption of a fiery red mane. For Loud, she wasn’t going to let her demons hold her back, and she wasn’t going to ignore them either.

Before she built her own fashion empire, supplying the same products that she once said excited her, she was discovering newfound ferocity through her music. "S&M," Loud's shocking and exciting opening track, proudly asserted that "pain is for pleasure" over a buzzy keyboard and clubby drumbeat sterilized the sampled melody of the Cure's "Let's Go To Bed." StarGate and Sandy Vee's production might have aged a bit limply, but what makes the song a Rihanna classic is her vocal delivery, from velvety to prickly, from sensual to fervent. As opposed to "Disturbia," she’s completely unleashed herself. There's no Auto-Tune restraining the slight grit in her voice. She sounds like she isn't singing for anyone but herself.

A month before the album's release, Rihanna told SPIN that she saw the BDSM-inspired track as a metaphor. "It's more of a thing to say that people can talk….people are going to talk about you, you can’t stop that. You just have to be that strong person and know who you are so that stuff just bounces off." The accompanying video illustrates her tempestuous relationship with the press: She dawns a ball gown covered in tabloid headlines surrounded by a dozen reporters wearing ball gags. Crude jokes such as “COX NEWS” and “Princess of the Illuminati” flicker across the screen. At one point, gossip blogger Perez Hilton is tied up like a dog, and Rihanna playfully spanks him on the booty — a metaphor come to life.

Rihanna had evolved the image of "good girl gone bad" past superficial means. Things were getting intimate, and complicated. “I do think I’m a bit of a masochist,” she told Rolling Stone, referencing childhood turmoil. “It’s not something I’m proud of, and it’s not something I noticed until recently. I think it’s common for people who witness abuse in their household. They can never smell how beautiful a rose is unless they get pricked by a thorn.” It’s this self-awareness that has allowed Rihanna to sustain the shadows in her music, balancing the light and dark.

“S&M” was a bold introduction to the new era of Rih. She experienced trauma and abuse with millions watching, who were taking stock of how it affected her music, and judging how she was handling something deeply personal and unnerving. It would be distressing even if you didn’t have gossip blogs chiming in. Instead of shrinking under the public scrutiny, she found a way to be revitalized by it.

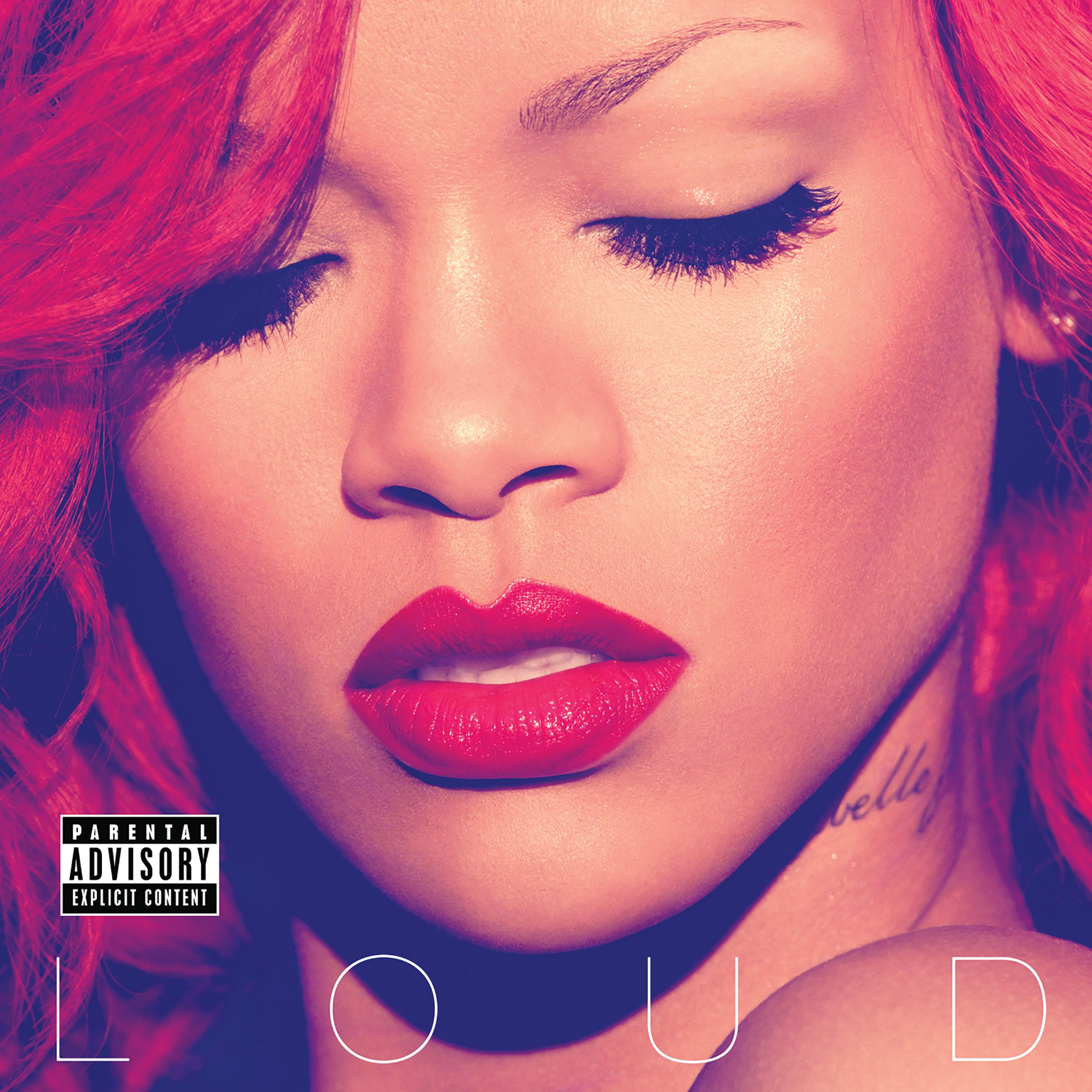

It’s important to understand that Rihanna is an artist that cherishes duality. It took her a few albums to establish that balance, and she continues to evolve her image and career in an innovative grey area. On Loud, she begins to successfully layout that complexity without being so on the nose as Good Girl Gone Bad. Even the album cover is a combination of boldness and intimacy. The frame of her face and lips are consumed by that cocksure red. She’s baring part of her teeth, but her eyes are closed as if frozen between confrontation and unawareness.

In retrospect, Loud feels more empowering. Rated R might be understood as a documentation of a harrowing chapter for the then 21-year-old, but Loud found Rihanna comfortable in her own skin. “Life’s too short to be sitting around miserable,” she sings, her voice heavy with whiskey, on the party revival track “Cheers (Drinks To That).” It samples pop-punk princess Avril Lavigne’s hit “I’m With You,” a track that searches for counsel and connection. Rih’s flip still searches for comfort and release, taking a Jameson shot-popping zen approach. Life’s ebbs and flows will go on regardless of what people believe. “People gon’ talk whether you be doin’ bad or good.” It finds embracing freedom and hedonism without denying they exist alongside life’s thorns.

Despite not having any writing credits on Loud, Rihanna performs the hell out of this album. Over 200 songs were collected with the help of 27 songwriters and 32 producers for a full-length that had the hits like Good Girl Gone Bad and the depth of Rated R. On her roster of highly prominent writers and producers, she included Ester Dean, Sandy Vee, Tricky Stewart, Timothy Thomas, Polow Da Don, the Runners, Soundz, and StarGate. If not the writer, Robyn Rihanna Fenty was the inspiration. The goal was to craft songs that only she could sing, nothing in the wheelhouse of her compatriots Kesha, Katy Perry, or Lady Gaga. (Although “Raining Men” does sound like it missed the cut for I am...Sasha Fierce.) She asserted that, at the time, it was her most “Rihanna” album yet.

Listening back to "Only Girl (In The World)," I’m brought back to high school dances and the precipice of the EDM revival, which she would push further into with her Calvin Harris collaboration the following year. So many years later, "Only Girl" is one of the most important songs Rihanna has ever recorded. It’s a prelude to "We Found Love” and a validation of her own being, enough so that she’s the only one that matters in that moment. It’s complete euphoria. Despite the hues of pink and abundance of flowers, there’s a sense of urgency and intimidation as drum and bass percussion and an agitated bassline writhe during the chorus. In the video, she stands in a field of flowers like Dorothy in the field of poppies, but it feels apocalyptic with the heavy saturation of red. As the lead single, it’s a turning point for Rihanna. Loud was the most alive she had come across on an album.

Rihanna is not a perfect singer, she’s a powerful one. In the short documentary film Loud In The Making, she explains her pre-show routine. She takes a throat lozenge and then smokes a cigarette. She doesn’t like smoking, but it brings out a raspy quality in her voice. Rihanna’s vocal dynamism is one of her music’s charms. She reaches a near operatic belt on “Complicated” and then struts breathy pine on the Enya-sampling “Fading.” The penultimate “Skin” is one of her underrated songs, suspenseful and sultry. “No heels, no shirt, no skirt,” she schemes. “All I’m in is just skin.” It’s the most stripped-down track with minimally warped synths and a stealthily, popping drumbeat. It’s in the same vein sensuality that she would perfect on 2016’s Anti with tracks like “Desperado” and “Needed Me.” It also happens to be the song where Riri conjures her rock goddess sound the best, featuring the swooning growl of Nuno Bettencourt’s guitar work, which would later feature on Anti’s “Kiss It Better.”

I guess we should probably talk about Drake too. Regardless of whatever feelings you have for the Canadian rapper-singer, the magic of their musical collaborations is undeniable. The second single from Loud, “What’s My Name,” is the first track the pair published (they had recorded a track for Rated R but it didn’t make the album). Following “S&M,” Rih is again putting her needs first, making sure he can satisfy her, seeing if he’s worthy of her. There is power in naming. A take on the Destiny’s Child classic “Say My Name,” “What’s My Name” is a reclamation of her sexuality. Her Bajan drawl is emphasized alongside billowing synths and syncopated drums, foreshadowing Rihanna and Drake’s leveling-up six years later with “Work.”

Rihanna’s choice to be her own muse has been her best. It’s trickled down to her fashion and beauty lines, but this acceptance of herself began to take shape with Loud. In a few ways, the album is a precursor for the Savage entrepreneur. It’s a collection of songs that showcases her balance of masculinity and femininity, one she currateted in order to depict a fun and vibrant atmosphere. It embodies what she’s manifested in her lingerie and makeup businesses — a way for herself and the world to universally feel sexy and confident. For her most recent Savage X Fenty fashion show, Rihanna discusses how personal sexuality is, that it "has to be owned and earned." Loud is evidence that she’d done both.