Near the end of Slow Century, Lance Bangs' 2002 Pavement documentary, we happen upon a seated Stephen Malkmus, playing a new tune. Offscreen, Bob Nastanovich’s keyboard wheedles wonkily and drummer Steve West sustains an encouraging beat. Onscreen, the camera is trained on their frontman and the guitar he's strumming. It’s an intimate, awkward interlude, captured in desolate performance-space surroundings. The lyrics as sung are underbaked and unsure of themselves, little clear distinction is made between verses and choruses, and no ending exists. Still, there's promise -- Malkmus' laconic vocal veers north in startling ways, the melody sparkling, the words a cryptic jumble. It's sometime in the late 1990s, and Pavement remains a beloved American indie-rock band that hasn't broken up yet. "That’s a good song,” the singer remarks afterwards. "We should do that."

At this point a narrator might have interjected: "Pavement did not do that."

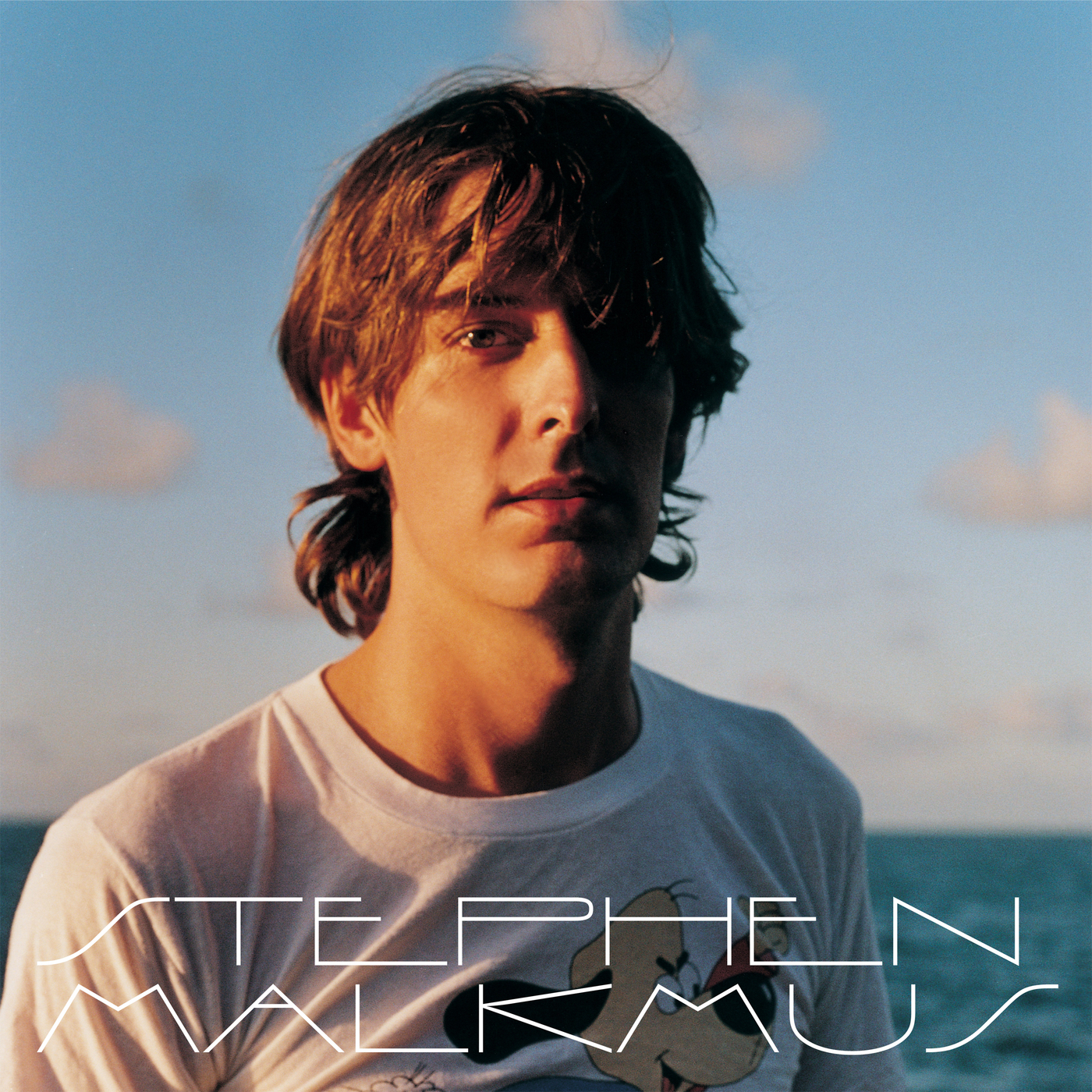

"Discretion Grove" instead appears almost halfway through 2001’s Stephen Malkmus, the marquee mark's debut solo LP, which turns 20 years old this Saturday. Studio-realized as a Ramones-esque choogle chug with a pickup backing band of fellow Portland, Oregoners he christened the Jicks -- bassist Joanna Bolme, drummer John Moen, and percussionist Heather Larimer, who was Malkmus' then-girlfriend -- the song remains an inconclusive curio. It's a song that sounds like a trailer for itself. Two decades later, "Specialized victories, for over-age whores/ I felt up your feelings" is still a double shot of provocative, oblique shade, but in every other respect it’s woefully out-of-sorts: the arrangement jittery and unsettled and unsatisfying, the lyrics a mess, the loony video treatment signaling willful inanities to come. "Discretion Grove" sticks out like a sore thumb on Stephen Malkmus, the fly-in-the-ointment on a record where, by contrast, every other cut is confident, engaging, and self-assured.

Pavement finished its final pre-reunion tour in November 1999 and broke up via a bizarre game of telephone the following year. Sad? Yes. Surprising? Not really. Over a decade-long run, the band emerged as Malkmus' enterprise: He wrote and sang most of the songs and laid down many of the parts for a group whose members were ultimately geographically scattered. Things were getting heavy; an ennui was setting in. "I was just tired of doing the same thing over and over, different song progressions that were starting to sound the same,” Malkmus told Thomas Beller of the blog Mister Beller’s Neighborhood in an early 2000 interview. "If you stick around for 10 years you should be 10 years better than young bands, try extra hard to be interesting. It didn't feel like that was happening. It's hard to teach an old dog new tricks. Or a 30-year-old male." 1997’s alternately spastic and elegiac Brighten The Corners and 1999's vaguely British Terror Twilight certainly have their partisans -- I have soft spots for "Transport Is Arranged" and "Fin" from Corners and "You Are A Light" and "The Hexx" off of Twilight, myself -- but it'd be a real stretch to call those albums exciting or fun.

A creative reset of sorts, Stephen Malkmus is zany and playful. Its working title was Swedish Reggae, and daubs of dub do bubble up here and there, remnants from some lost earlier iteration. A whimsical glee radiates from quickie "Troubbble," its bratty, gang-chanted denouement literalizing the chorus, its verses a Scrabble-board scatter; it would sound right at home on the soundtrack to a children's TV show. Interpolating a Yul Brynner interview snippet upfront and a Bob Dylan lyrical quote on the backend, the raucous, soaring "Jo Jo’s Jacket" is an ejaculatory rollercoaster of gags, effects, and affectations -- the psychic indie-pop equivalent of a Saturday Night Live "What's Up With That?" skit. The bright, dinky "Phantasies" sustains this silly streak with handclaps, mapbook flips, and theatrical echo. The pirate ship-themed "The Hook" shamelessly rips off Creedence Clearwater Revival's "Proud Mary," locating an allegory of transition via received cliches. The deadpan, spectral "Deado," which would fit nicely on a playlist between selections from Beck's Mutations, is home to a bizarro non-sequitur the "Loser" star probably still (privately) envies: "I can't employ the tactics/ Already, rented them out to my friend Snake/ The equinox tail-chaser, super frail."

Even when the mood turns somber or serious, every moment of this record seems to overflow with winks and an understated, joyous wonder that writing and recording music can be pleasurable and rewarding. There's something special, something extra, in the grain of Malkmus' vocals here -- a complete commitment to and investment in whatever bit he's lined up for himself. It's there in his distracted, space-case croon on the piano- and pedal steel-saturated mythomaniac bummer "Trojan Curfew." Not only is "Church On White" startlingly gorgeous, it's also, to this day, the most profoundly affecting tune Malkmus has ever penned. Written to eulogize his late friend and novelist Robert Bingham, who died of a heroin overdose in late 1999, the song bears an unusually emotional charge, but the dourness that might have darkened the proceedings is sidestepped. There’s a lightness, a benediction; sonically, this is a homegoing, not a funeral dirge. Malkmuns' guitar lines here, glancing and incisive and chiming and precise, are more than a match for the accompanying sentiments: "Carry on/ It's a marathon/ Take me off the list/ I don't want to be missed/ Carrion/ It’s what we all become/ From small minds and tall trees/ Away from the action."

The banger destined to be recalled (semi-fondly) by your Pavement-loving fellow travelers who bailed on Malkmus around the advent of Hurricane Katrina is, inevitably, "Jenny & The Ess Dog." If "Church On White" is the heartstring tugger, the affable, Phish-acknowledging "Jenny" stands out because it's catchy, narratively linear, and immediately relatable: an accessible, digestible story song, unshackled from the hoary Simon & Garfunkel and John Cougar Mellancamp tropes of the form, about outgrowing and leaving behind childish things. (Off with those awful toe rings!) As a not-so-subtle metaphor for Malkmus' own solo career, this single is balder than "The Hook." But it's worth remembering that a) the Jicks' lineup would prove to be more malleable than Pavement’s ever was and b) every solo and Jicks-labeled LP to come would represent another reinvention. Stephen Malkmus reset the baselines to something looser, giddier, even louche; weirdness and aesthetic complexity beckoned beyond.