We’ve Got A File On You features interviews in which artists share the stories behind the extracurricular activities that dot their careers: acting gigs, guest appearances, random internet ephemera, etc.

When I caught up with Juliana Hatfield by phone last month, she'd just been landscaping someone's yard, replacing fake grass with stones. "We had to dig the whole thing, and then haul all the dirt, and then we put down a sub-base and some fabric, and now we're doing the pebbles on top," she says, catching her breath.

She's merely helping a friend with this "very repetitive and tiring" job, Hatfield explains; it isn't her new side hustle. Not that it would be so surprising if a successful indie artist pivoted to manual labor during the pandemic that's halted all concert tours.

When she does hit the road, the singer/songwriter will have a sharply hooky and darkly comic new batch of tunes in Blood, out today. It is Hatfield's 19th (!) solo album, including a couple credited to the Juliana Hatfield Three, but not counting the ones from Some Girls (her band with Heidi Gluck and Freda Love Smith), Minor Alps (with Matthew Caws), the I Don't Cares (with Paul Westerberg), or her first group, Blake Babies. She played bass in the Lemonheads, too.

Hatfield lives in Cambridge, MA, a stone's throw from the clubs and studios that incubated the vibrant Boston college rock scene Blake Babies helped cultivate in the late ‘80s alongside the Lemonheads, Buffalo Tom, Throwing Muses, and others. It's where she's been producing and playing almost all the instruments on her albums for decades. But stuck at home like everyone else last year, she gave in and (with tech support from remote collaborator Jed Davis) learned how to use GarageBand.

The result is a collection of scruffy and purgative power-pop inspired by the violence of the Trump era, a world "controlled by fascist blood-sucking thugs" as she sings on "Nightmary." Over a bouncy riff and distorted beats in "Chunks" she warns her target that someone's gonna chop them up and put them into garbage bags. In the fluttery new wave fantasia "Had A Dream" she stabs a traitor in the neck: "then I pulled it out and I stabbed you again." But her vengeance isn't necessarily directed at one person, short-fingered or otherwise "There's an endless list of people who need to be punished," Hatfield clarifies.

Her biting sentiments are carried in sugary melodies and a delicate, distinctive voice early fans and critics alike always described as "girlish, angelic, virginal, coy," she recalls. It's a juxtaposition that made songs like "My Sister" and "Everybody Loves Me But You" favorites of the MTV Buzz Bin era.

It doesn't quite qualify for the ephemera we include in these career-spanning interviews, but in preparing for our trip down memory lane I came across a brief clip for Blender back when it was a CD-ROM magazine. Hatfield's sitting on a mushroom sculpture, saying, "I guess I'm the angel-type to some people, but my evil side will come out one of these days." That's true, she admits, but her lyrics have always been dark. "There's a lot of violence in my lyrics going back to the Blake Babies, so I definitely am in touch with my dark side," Hatfield points out. "Hopefully, it'll only come out in songs, and not in real life. I'm really not a violent person. I can't even kill bugs."

Check out our Q&A below, which touches on some of her many recording projects, Beavis And Butt-Head, music industry frustrations, Evan Dando, and Phil Collins.

Blood (2021)

"Torture," "Mouthful Of Blood," "Nightmary" … I could ask if you've been watching a lot of horror movies or just living in America for the past four years.

JULIANA HATFIELD: Yeah, just the past four years of all that inspired the record. Plus, I do watch a lot of movies, and some of them are horror movies, Italian horror movies and others. I love that stuff. They're kind of campy and really overdramatic, and some are dubbed really badly so there is a comedy element to some of them.

Some people are afraid of their dark side, so they pretend it doesn't exist, and those are the people that go and explode. You got to just accept it.

Like in the song, "Had A Dream," everyone has those revenge fantasies. It's normal. It's part of being human, but you don't want to go and act out those horrible acts. You don't want to do those horrible things in real life.

It's frowned upon.

HATFIELD: It definitely is, and I don't think it would actually feel good if you carried some of the violent fantasies. It probably would feel really bad.

I saw your last show before lockdown, at Music Hall in Williamsburg, and I've watched some of the recent livestreams in which you played your albums in full. The vibe was pretty similar, but I was wondering how you feel these virtual events have been going.

HATFIELD: I always feel like I didn't do a good enough job. I have the same old self-criticism that I have of all my performances, so that's the only problem I have. I feel like I haven't really completely nailed a show yet, a livestream show, but that doesn't really have anything to do with the format.

It's kind of nice to be able to just get up and drive a couple miles to the studio, and then play an album, and have people all over the world be able to check it out for free, and it seems to make certain people happy, which is good.

I'm not using any third party or middleman. I'm just doing it. There's no ticketing system. It's just directly to the people, so that makes it easier for me. I initially was checking out a couple companies that did the ticketing and the broadcasting of it, but I just couldn't deal with... I didn't have enough autonomy within their systems, and I just wanted the freedom to have it just be my own thing, so fortunately Q Division [Studios] was able to do it with me, and they're my friends, so it's good.

The shows are free, but viewers can donate.

HATFIELD: Yeah, and they have.

Blake Babies - "Nirvana" (1991)

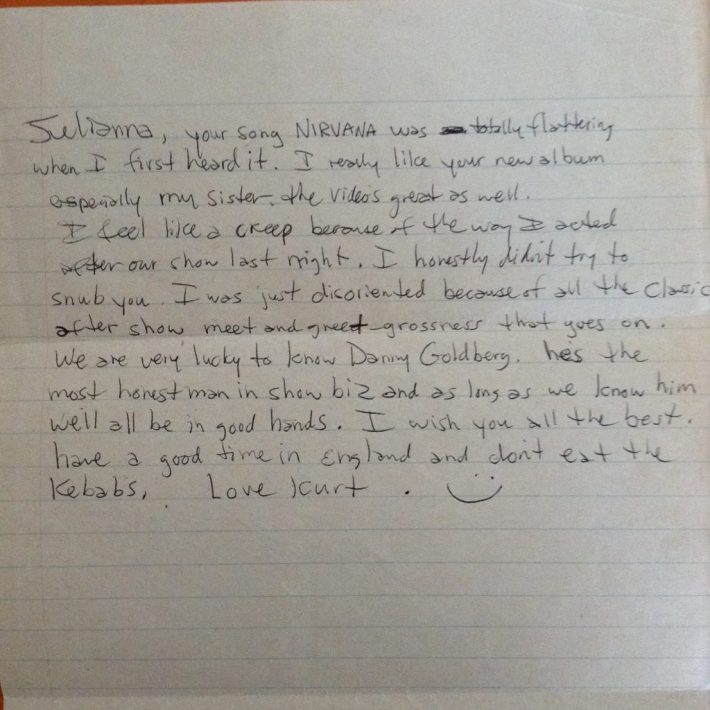

A few years ago you wrote about this letter you received from Kurt Cobain, and how you had considered selling it. I'm assuming you didn't sell it.

HATFIELD: I did not sell it. I really don't want to sell it. It's not that I'm a collector of stuff like that. I don't have a lot of memorabilia. I don't have it framed or anything. It's just in a drawer somewhere, but yeah… I wasn't actually going to sell it.

Sometimes after I write something, I look back and think, "Wow, why did I share that stuff with people?" Because it was a personal letter from Kurt to me, and maybe I shouldn't have shared it, but I don't think Kurt would mind, really, looking down on it. I don't think he really would have minded if I shared it.

Your song "Nirvana" was one of the last things people heard from Blake Babies, before you went solo. Of course you guys reunited a decade later, but that final 1991 tour was tense. At one point Freda left in the middle and was replaced by your brother.

HATFIELD: Yeah, and he wasn't really a drummer. It was kind of an awful time. I don't even remember why Freda left, but she wasn't happy, and then the rest of the tour was miserable because the drummer... We were just scrambling to play these shows, and it was really not fun.

Is this the brother whose girlfriend took you to Violent Femmes and the Del Fuegos or a different brother?

HATFIELD: No, it was a different brother.

Hey Babe & The Lemonheads' It's A Shame About Ray (1992)

You rerecorded "Nirvana" for Hey Babe. Former Blake Baby Evan Dando played on that album, and you played on Lemonheads' It's A Shame About Ray, which came out a few months later. What do you remember about that busy time?

HATFIELD: I remember going on tour opening for the Lemonheads, and it was me and a drummer and bass player. I think it was Bob Weston on bass who played in the Volcano Suns and Shellac. He played bass, and this guy Paul Trudeau played drums, and then part of the Hey Babe tour was that, opening for the Lemonheads. I remember a few of their shows, but not many. It was kind of exciting for me because it was my first time as the only guitar player in a band, so I was really scared before the tour like, "Can I handle being the only guitar player?"

https://twitter.com/julianahatfield/status/746015758854070273?lang=en

Did you see Evan playing "Confetti" in a Walgreens for someone that found his wallet a few months ago?

HATFIELD: I did see that, yeah. That was cute. I think it's the Falmouth, Massachusetts Walgreens. It's the town where the ferry to Martha's Vineyard is because Evan lives on Martha's Vineyard.

"Universal Heartbeat" On The Late Show (1995)

https://youtube.com/watch?v=GA4cmol0DXM

You played all the guitars on Only Everything; it's funny in this Letterman clip there's like five guitars on stage. Evan's in there too.

HATFIELD: They asked us, "Can you play tomorrow night on Letterman?" I think Aretha Franklin had cancelled, so they needed a musical act, and then I was like, "Oh, shit, this is really scary. I need a friend," so I called Evan just to... Not because I really needed another guitar player, but because I just needed a friend with me because I was scared.

Acting On "The Adventures Of Pete & Pete" & "My So-Called Life" (1994)

By that point you had done a couple of TV cameos. Did you hope these would lead to more acting gigs?

HATFIELD: I did not really have acting ambitions. ["My Sister" video director] Phil Morrison was a friend of mine, and he asked me to do that Pete & Pete. The My So-Called Life people initially asked me just to write a song, and then after they met me, they offered me the part.

I tried to act and to get into it, but I never really took to it. Acting is just like such a strange world to me. I was not good at it or I just never could really lose myself in that to be able to understand another character, what it means to become another character.

Beavis And Butt-Head (1995 & 1996)

You also landed two videos from the same album on a season of Beavis And Butt-Head, which is quite a coup.

HATFIELD: Yeah, that was the highlight of my career, I think, being on Beavis And Butt-Head twice. Those are also Phil Morrison-directed videos. Even back then, I was exploring blood, so it's a theme in my work.

Yeah, and I mean, in My So-Called Life I played a dead girl. I was an angel. She had died, so darkness is a theme.

Unreleased God's Foot Album (1997)

In that Kurt letter, he mentioned how you were both in good hands with [Nirvana manager and Atlantic president] Danny Goldberg. I take it by the time the label rejected your Only Everything followup God's Foot, he was not there anymore.

HATFIELD: I think he was gone before Only Everything, even, or he left around that time, and I knew... "I'm screwed with this label." I just kind of sank down to the bottom of the roster, as soon as Danny left. I was not a priority anymore, and no one cared, so that's what happened.

God's Foot is one of those famous lost albums and I know you weren't thrilled when it eventually leaked unmastered and unsequenced, and presented like an album. You tweeted a while back asking if should you rerecord it, and hinted that maybe you'd get the masters back?

HATFIELD: Sometimes I think about it, like when I get the masters back, will I release it? Is there any point to that, and then I thought for a minute about rerecording the songs, and I was like, I don't have the energy to do those songs that don't really feel so current to me, to my thinking anymore. It might be weird to sing some of the songs now, and I only was thinking about this stuff because people out there seem to want it to be released officially.

https://twitter.com/julianahatfield/status/966441152617631744

I don't really care that much, but it's not something that I have a burning desire to do, to release the album officially. If I did own the masters, I would release it just so people could have an official version of it in the sequence that I want because there are some songs out there that I would not have put on the album.

"Fade Away" and "Mountains Of Love" were rescued for your greatest hits CD, but they're not on streaming services.

HATFIELD: I think the label at the time, which was Zoë/Rounder, they were able to negotiate [with] Disney or Atlantic a license for a certain amount of years. I have investigated trying to buy back the masters, and it was way, way too expensive for what they wanted.

I never understood. They wouldn't give them back to me, but they also didn't release it. The label could have made money if they released it, or they wouldn't have made money, but they maybe would have lost less.

I'm glad that people were able to steal the songs out to the internet, I guess. And I think people want to pay me for the album because they have it already. That's very generous.

"Sellout" (1997)

After Only Everything fans may not have understood how inhospitable the industry was for you. And the next Juliana Hatfield song anyone heard, ironically, was "Sellout," which opened the Please Do Not Disturb EP. Under different circumstances, it could have been such a big, cult rock hit.

HATFIELD: Yeah, I feel that way about a lot of my stuff. I feel like, "Why isn't this huge? What is wrong? Am I cursed or something?" Because there's some songs and some albums that I feel like could have been received differently in the world, but I don't know why. I guess it's just my fate that I'm going to live in relative obscurity, which I think kind of suits me. I think my timing is always wrong… or [joking] I'm just an unpleasant bitch in person.

It's weird. It's just some kind of thing that I was never able to figure out or I never played the games that people play or maybe I'm just not as good as I think I am. I don't think I'm that good, actually. Maybe, that's probably the problem. Also, the bottom line is that I don't have a lot of confidence or I've never had a lot of confidence. I have more now, so maybe that was part of the problem.

I never knew how to sell myself to people.

I hate promoting myself. Now, everyone has to do their own promotion on Twitter and Instagram and everything, and it's like, fuck, why do I have to tell people I have an album out? I hate even just saying, "Hey look, I have an album out." But I know it helps Joe at the record company when I let people know that I have new stuff for sale.

Juliana Hatfield Sings The Police (2019)

Is it true that you were thinking of doing a Phil Collins covers album before you decided on the Police?

HATFIELD: I was, and when I was exploring Phil Collins, that led me to the Police because I was listening to that ballad on which Sting sings backup vocals, "Long Long Way To Go." And then once I heard Sting come in, I'm like, "Holy shit! I love Sting more than I love Phil Collins," so then I have to do the Police. Duh! I love The Police so much, and so that's when I switched over from Phil Collins to the Police.

Sting is my favorite artist. I saw you backstage a few years ago and for some reason ended up showing you my ridiculous Phil Collins—

HATFIELD: Oh, my God. Your tattoo? That tattoo is amazing.

Following Olivia Newton-John and the Police, are you set on an R.E.M. covers album next?

HATFIELD: No. I'm still thinking about it, actually. Part of me now wants to do Liz Phair. She tweeted part of [a new] song, not "Hey Lou," but a different song. It was so good! Just like 20 seconds or something. It was like, "Gonna leave you with my good side." The way it went into the chorus was so glorious. I loved it so much, and the sound. The drum sound is so bitching. Is it Brad Wood, this one?

Yeah, it is. We're gonna subject her to one of these interviews, too.

HATFIELD: Tell her I say hi. But yeah, I'm still exploring my options. I do want to do an American band just because why not? I've done Australian and English, so I should probably do one of my countrymen at this point. Props to American music, you know?

The I Don't Cares - Wild Stab (2016)

Speaking of great American bands, you wrote evocatively in your memoir about watching the Replacements on SNL back in the day. I'm sure you were thinking, "One day, Paul's going to call me up and ask to make an album with him."

HATFIELD: No, I was just thinking, "One day he's going to meet me, and he's going to fall in love with me!" That's what I thinking.

How did your collaborative album come about?

HATFIELD: I met him a long time ago. There was a tour booked. Paul Westerberg was doing a solo tour, and maybe it was for 14 Songs? It might have been that tour or maybe the next album. I was invited to open some shows, and so it was like my dream come true. I was like, "Holy shit. I'm going to open for my idol." I was headlining my own shows, and then we were going to meet up with the Paul Westerberg people at some point, and then I got word that he threw his back out, and he had to go home and cancel the rest of the shows. I was pretty heartbroken.

Evidently, I was on his radar or my music was, so that led to our meeting at some point. He was in Boston, and I met him, and that was more than 20 years ago. By the time I Don't Cares was an idea, we had known each other for a long time, and we were just hanging out.

He would start playing recordings and songs of his that I had never heard, and I'd be like, "What is that? It's so great!" And he'd be like, "Just some demo I made in my basement," and I think that's how the thing started. I was encouraging him to show me more stuff, and he was writing, and I was telling him the stuff is great.

I was just around, and we just started kind of sharing on some of the recordings, and then we started writing a little bit, and we recorded it in his basement.

Everything else he's released in the past 16, 17 years has been under some alias or with really limited distribution.

HATFIELD: I wish he would keep releasing stuff, but he kind of went silent. But who knows? There might be something out there now that we don't know because it's under a different name.

Blake Babies - Earwig Demos (2016)

Around that time there was also a vinyl-only release of Blake Babies' second album demos.

HATFIELD: That was the project that I was least involved in of anything that I've ever done. I was disengaged completely. I think I was just overwhelmed by stuff at the time. Someone unearthed the demos, and they're like, "Can you sign off on this? Are you cool with this?" I'm like, "Yeah," but I have not actually listened to that album. I haven't heard those demos since the day that they were made.

Freda has said neither of you could even remember where you recorded it.

HATFIELD: Usually I don't let anything get out to the world until I've completely signed off on it and approved it, but I was so disengaged with this project, and I don't know why, but I think I just trusted John [Strohm] and Freda. I guess part of me didn't want to hear myself back then because my voice was so earnest, and I thought it would make me cringe to listen to it, so I never did.

It felt kind of nice to let the others take control because I'm usually the boss of my projects, and I have to oversee everything, and I have to micromanage every little thing, and it was kind of a relief to not care and just let it happen.

The Juliana Hatfield Three - "If I Could" (2015)

Earwig Demos was crowdfunded, as was the Juliana Hatfield Three reunion album that preceded it. Can you tell me about "If I Could"? It sounds like it could've been on the band's first LP two decades earlier.

HATFIELD: I made a demo of it in 1998 or something [and] it kind of got lost. I always thought it was a really good song, but it was written and recorded in that weird time when I was between labels. This guy from [another major label] commissioned some demos from me at that point when I had left Atlantic. [Producer] David Kahne was interested in me for a while. He commissioned some Blake Babies demos at one point. He produced them, did a version of "I'm Not Your Mother." John and Freda thought he was too slick, and they didn't like the result, but then he kind of followed my career, and when I left Atlantic he set me up with this guy in Conshohocken in Pennsylvania who had a home studio. He was a drummer, and we made some slick demos over there, and one of them was "If I Could," a different version, a second version. So there were two different demos of it before I made Whatever, My Love with Dean [Fisher] and Todd [Philips] years later.One of the songs from that Conshohocken session was "Cry In The Dark" [from 2000's Beautiful Creature]. There's another one called "Baby It's Alright," I think. I don't know if that one's out there. It's just I think a demo that never got out into the world.

You had a lot of success with PledgeMusic before they imploded. And you were talking earlier about how you've cut out the middleman with the YouTube livestreams. Are these direct-to-fan platforms decidedly better than the major label system or you're working twice as hard for half as much money? On the new song "Suck It Up" you sing, "We creatives, we always find a way, when a door closes, we just open a vein."

HATFIELD: It's bad and good. It's both. Now, I have to do more jobs that I maybe don't want to do like—

Landscaping.

HATFIELD: Actually landscaping... that's what I really want to do with my life. I want to join a landscaping company, but I'm doing that for fun. Yeah, so now I have to tweet and stuff. I have to promote myself where there used to be a promotion department at the label. When I was running my own label [Ye Olde Records] I had to be the accountant. I had to hire graphic designers. I had to press CDs. I had to accept the boxes. I had to put them into mailers and go to the post office. There's just all these jobs that there's more to be done when you're doing it yourself, obviously, but it's great to get the money directly from fans because labels really cannot be trusted to do accounting honestly. Who knows how many millions of dollars have been withheld from artists who are entitled to the money. It's expensive to audit a major label. It's great to just be able to have fans, if they want to, donate to the cause. They can give it right to you, and that's a really beautiful thing. The fans like that too, because they know that it's going into the pocket of the artist that they like, and it's helping the artist to be able to sustain a career.

//

Juliana Hatfield's Blood is out today via American Laundromat. For another week you can watch her virtual record release show below, and donate here.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=eltZcQZnZh4