With Megabear, Myles McCabe's band has crafted 52 songs that fit together in any order. Seriously!

South London’s ME REX started in 2015 as the densely worded solo endeavor of Myles McCabe but wouldn’t stay that way for long. After a few years of occasional collaboration, McCabe would officially fill out the band with UK indie punk familiar faces Kathryn Woods (Fresh, Cheerbleederz), Rich Mandel (Happy Accidents), and Phoebe Cross (Happy Accidents, Cheerbleederz) culminating in an expanded rerecording of the two original EPs, Stegosaurus and Triceratops, which were then released as a double EP late last year.

More than just a building out of instrumentals that can be seen on earlier releases, the transition away from a solo project is felt heaviest on Stegosaurus and Triceratops through the near constant chorus of voices enveloping McCabe’s characteristic breathless delivery. Themes of alienation, cyclical growth, and change weave ME REX's discography together in a way that seamlessly marries the almost psalm-like EP Wooly Mammoth with the indie pop sensibilities of last year's double EP.

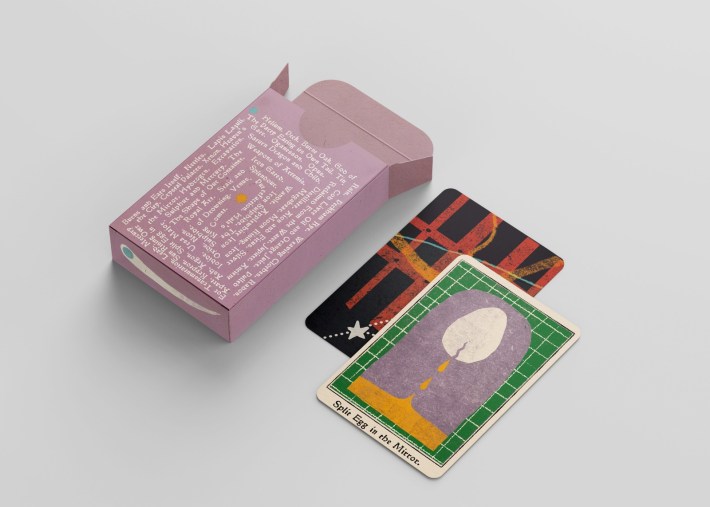

In that way, their debut album, Megabear, is less of a departure from what makes ME REX a great band and more of an extension of the dinosaur-themed world Myles McCabe has built for himself. Through 52 short cells asked to be played on shuffle -- each with its own card in a customized deck -- ME REX call back to those recurrent themes not only through self-referential lyrics, but in the structure of the album itself. Megabear is an album, it is one song, and it is countless different songs all at the same time. There is no beginning or end. It's an exercise in intentional unintentionality. The project is an experiment in breaking away from traditional album structure, but what’s central to the success of the concept is how it makes the central themes of the album -- alchemy and the chaotic, natural change in human experience -- tangible on each listen.

I talked to McCabe via Zoom about gimmicks, gaming the streaming system, and transmutation to figure out why, and how, someone makes an album that demands to be treated as one whole piece of art by breaking itself into impossibly tiny parts. Preview the album's quasi-single "Galena" and read our interview below.

What inspired you to break away from the traditional album sequencing structure?

MYLES MCCABE: So initially I wanted to kind of break away from it in the other direction, and I was going to try and do a really long song in the style of Sufjan Stevens or Joanna Newsom or one of those people. Then kind of simultaneously, I had the other idea as well, which was a bit more out there, of having these really short cells, but that idea was that each one would be literally one line long. And the rhyme structure of it would be AAA. So every line rhymes with every other line I did. I didn't get very far with that.

But it [came about] while I was listening to a podcast, The Blindboy Podcast. Quite recently he's talked a lot about the way the music is, or any art form really, is affected by the environment that it comes about in. And something that he addressed a long while ago now is the way that the grime music is so well suited to streaming because the songs are short. And so, you know, you rack up a lot of plays that way it just kind of makes sense. So that's kind of when I had the idea of merging those two things. So I went and checked how long a song has to be for it to register as a play on Spotify. It's 30 seconds. That makes it sound like it was this kind of, you know, cynical cash grab of all those pennies that I would get out of Spotify. And in a sort of tongue in cheek way, to sort of overblow it, it's kind of an artistic intervention. I've been writing five-minute songs and that counts the same as the 30 seconds. Yeah, and they've been bugging me off, so this is my revenge.

Could you give any insight into how you actually wrote to make the songs always work together?

MCCABE: Well, a big part of this initially was kind of trying to do something that couldn't possibly work. It was well into even the recording stage, after over a year of writing, we had no idea whether it was going to work. We did decide to sort of push the boundaries of it in some ways, but also be quite cautious in others. So, like, compared to the other stuff we've done, it's not that dynamic. It's not got very many huge sections. At the same time, we still did stuff like it's actually not all in the same key and there's a couple of tracks on it that are in 6/8 or 3/4.

How did you decide which songs to put together to form a sort of regular single?

MCCABE: It was really tricky. We kind of debated a lot of whether or not we would do that as well. There's a strong argument that [the single] completely undermines the concept. It is one long piece of music and each one sits in the context of the whole, but then also, at the same time, they are individual songs and it's about the way that they interact with one another.

The single eventually came about [while] we were trying to learn to play the whole thing live, which again brings up that intentionality issue. So what we were initially going to do is try and film a session where we learned the songs in the order that they were recorded in and then the session would be cut and rearranged into various random orders. But it was just too hard. So I kind of rerecorded a basic version of a few of the songs and we changed the dynamics of it. It's out of that the single sort of developed.

How did you decide to sequence the album for the vinyl and Spotify and everything?

MCCABE: So the [vinyl] record order is fairly close to the order that the songs were recorded in, but there were certain things where we did it in blocks, so if there was an idea that gets repeated a lot, that would kind of come together. In some places it made sense to keep those in chunks so that you almost get a sense of like a conventional album, right? So you have the kind of song sections, repeated choruses next to each other, things like that. From there I literally just pressed shuffle on the iTunes and wrote down the order that it came through and I did that for two more official orders that will come on different formats.

That's neat that they’re all different, so there really is no official order. I’ve only been able to listen to it on the Megabear website where you’re really forced to listen to it in a random order, but it really does feel to me like one cohesive track no matter what.

MCCABE:As you might be able to tell, I am a big fan of kind of building in contradictions. So it's this cynical statement and it's a half-hour piece of art. And it's one song and it's 50 songs. And there's no intentionality, but also there are set orders.

Have you thought about how people will react to it? To the concept and the album as a whole.

MCCABE: Yeah, I mean, there is part of me that wants people to scoff at it and be like, oh, this is such an irritating gimmick and completely write it off. Having started it from a place of, you know, this is just a weird thing that a few people are going to hear and maybe some will like it, it's been quite freeing. The main thing that I would really, really love to see is other people doing a similar thing, because there's so much scope. That's almost the most exciting thing about it. Like there is so much more that you can do with this with this concept.

We've spent all this time talking about the format, do you have any concern about the music itself getting lost sort of behind that gimmick of the format of the album?

MCCABE: The scoffers are right to scoff at the gimmick.

Well, yes and no. The content of the album is so much about change and transmutation. Some of the main themes are alchemy, the transmutation of lead into gold as a metaphor for personal change and the chaotic nature of that and of natural reactions and formations. So it is kind of slightly tongue in cheek addressed in that there are lots of songs and it's one song, but also because there's no order it's not a song at the same time.

Certainly, for myself and I think for many others, music and songs are something that we use to process emotional events. I came across something while I was writing this that was just fully beyond anything that I had dealt with before and it brought up these feelings that I had never experienced -- that I just had no emotional language for. And it was through this [album] that I was able to process it and change from that and transmute that experience into something potentially useful.

Megabear is out 6/18 via Big Scary Monsters. Preview the album here and pre-order it here.