- Quote Unquote/Ernest Jenning/Really

- 2011

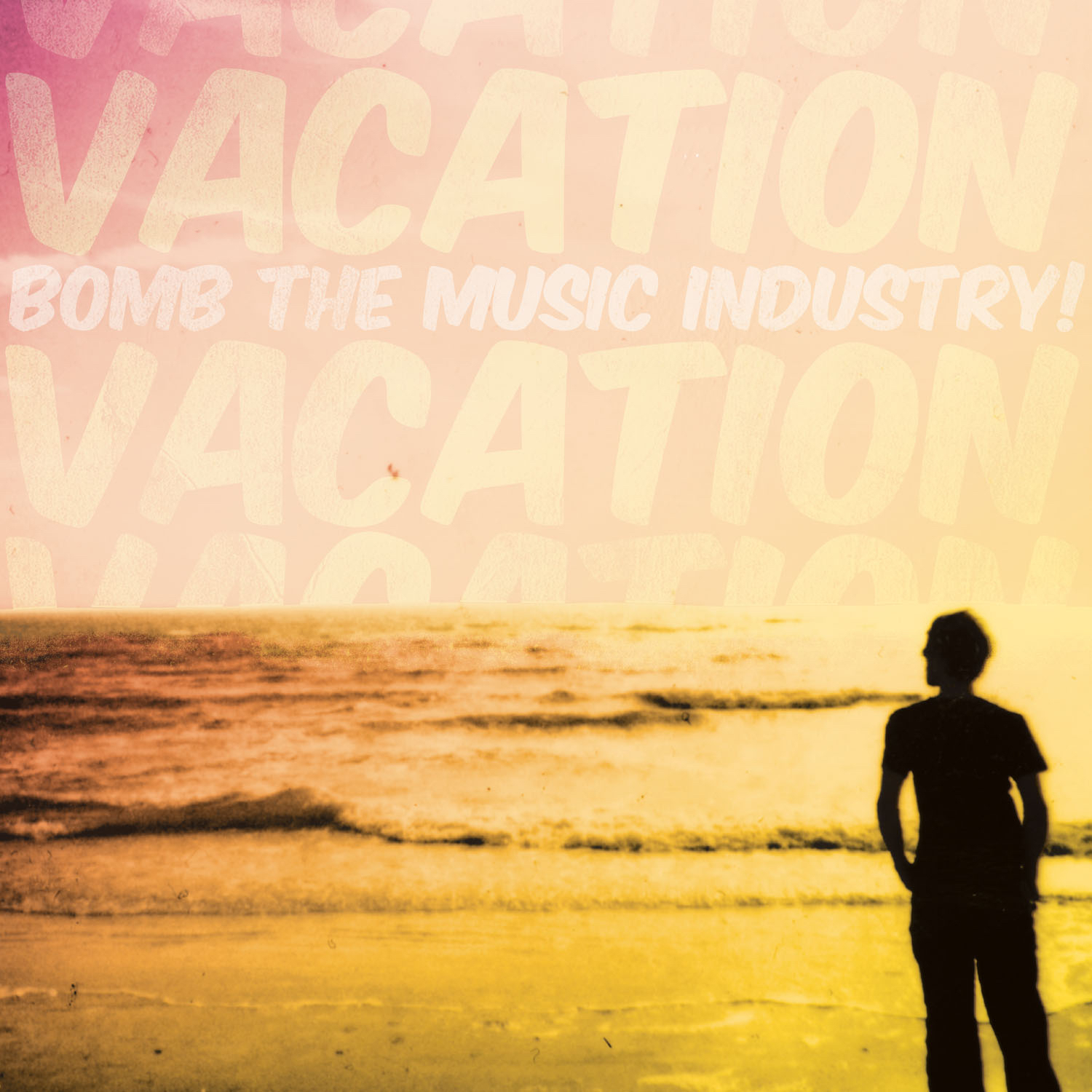

Vacation is supposedly a happy record. It has an "optimistic tone," its press release announced. "The band have been moving away from the dark introspection of their press material." But optimism looks funny from the perspective of Bomb The Music Industry!, the Brooklyn-via-Long Island group led by Jeff Rosenstock and supported by a rotating cast of characters. A "positive outlook," for a band whose songs often weighed another beer against total oblivion, is something like scraping by, against all odds. As their name suggests, Bomb The Music Industry! spent their entire existence in a constant fight against the commercial powers at be: they gave away their music for free; they tried to keep every show low cost and all ages. Every album underscored the existential threat of capitalism -- the fear that one day, their socialist ideal of free music for everyone would come crashing down.

Fittingly, their sixth record opens on a bike crash. "Campaign For A Better Weekend" finds Rosenstock skidding across a Brooklyn sidewalk after a run-in with a Ford Explorer, the crowd around him in shock as he picks himself up after the accident. "Keep on moving, busy street," he reasons as he bikes, bloodied, back to Boerum Hill. It's an apt metaphor for the band's trajectory -- they were a fixie bike, the music industry was an SUV. They survived by being agile, thinking fast, and when that all failed, being resilient. The song sounds immediately bigger and more grandiose than Bomb The Music Industry!'s previous records, starting humbly and ending in gang vocals, traversing both Brooklyn and time in the process: When he sings about a vacation he hates at the song's end, it's tough to say if he’s talking about an unreasonably nice day for a bike injury, or his half-decade spent in New York’s most principled, least defined indie rock band.

Bomb The Music Industry!'s intentionally profit-averse model was born from Rosenstock's frustrations with his former band, the Arrogant Sons Of Bitches. While the ska-punk six-piece was by no means an industry darling, self-releasing most of their records, their rise happened to coincide with the rise of third-wave ska. By 2003, they had transitioned from playing Long Island house shows to opening for Edna's Goldfish and successfully sneaking onto the Warped Tour lineup. By 2004, they were "getting paid between $300 and $1,000 for these shows [and] didn't really like each other all much," in Rosenstock’s words.

The Arrogant Sons Of Bitches found themselves in a difficult, though not uncommon, position for a rising act: They were big enough to warrant tours, but not big enough to quit their day jobs. Band tees seemed to be a sticking point for Rosenstock: The upkeep of merch inventory put them into thousands of dollars of debt, but the other members saw it as the only way to pay off their other debts from touring, recording, and promoting their music. By the time they broke up in 2004, their only remaining shows were largely to pay off credit card bills.

Rosenstock channeled both his frustrations with the music business and his broadening interests as a musician into Bomb The Music Industry! Not only would he self-record and self-release his first record, 2005's Album Minus Band, but he'd also give it away online for free. If a fan wanted Bomb The Music Industry! merch, they could just bring a blank tee for the band to spray paint at the gig; if they wanted an album, they could bring a blank CD and they'd burn one. Rosenstock was so dedicated to the accessibility of all ages shows that he wrote a song about them. And as the Grateful Dead learned long before Rosenstock, free and widely available distribution of your music is a decent marketing strategy. "People are coming to the shows because they heard the songs; they heard the songs because they are free on the Internet," Rosenstock later said.

Bomb The Music Industry! soon became synonymous with their radical, anti-capitalist approach to the music business. Rosenstock was invited on panels to speak about growing audiences organically; almost every interview mentioned their distribution model, often before any discussion of their music. So when, in 2007, Radiohead released In Rainbows using the same pay-what-you-want method that Rosenstock had championed for years, there was a brief question of how the band might continue: Rosenstock remembered thinking, "OK, so what I'm doing is completely obsolete."

But Rosenstock benefitted creatively from a shift in focus away from his modes of distribution. The band had already begun to explore more adventurous ideas, releasing a concept album about moving to Georgia (2007's Get Warmer, their fourth LP in just over two years) and balancing their early emphasis on hardcore and ska with a growing degree of punk and even pop. Rosenstock was clearly developing as a lyricist as well -- maybe he was sick of frat bros finding their shows from a song called "Showerbeers!" (sample lyric: "The only reason I take a shower is so I can drink a showerbeer"), but his focus began to turn away from a death drive to get drunk and towards existential questions about what it meant to grow up. "If you don't find someone to love now/ You will die freezing cold and alone," he bluntly professed on 2009's SCRAMBLES (arguably, a concept album about moving back to New York). The band also solidified their lineup, providing more consistency in recording and touring: They stopped doing "iPod shows," where Rosenstock would play the drums and electronics from an iPod out of necessity. They printed their first official T-shirts.

Vacation, like the two albums before it, is a location-based record. Rosenstock wrote most of it while on a prepaid trip to Belize, which he and his now-wife won by giving up their seats on a flight from Wisconsin for airline vouchers. The tranquility of his new surroundings seemed to have a palliative effect: Rather than commiserating over the drug-fueled narcissism of New York or homesickness in Georgia, Vacation reflects on Rosenstock’s life with a remove that mirrors his physical distance from home. "Sick, Later" looks back at a friend's near-death experience with a cathartic frankness; the aptly surf rock "Hurricane Waves" argues that a good day at Rockaway Beach is a cure for the blues (I have to agree). And even the pummeling "Felt Just Like Vacation" stares seasonal depression in the face and declares, "Winter won't kill me."

But the thesis of the album, and arguably of Rosenstock’s latter work as a whole, is "Can't Complain": He's got a bed, a drink, and a window to keep out the rain -- time may slip like sands through the hourglass, but hey, he can’t complain. It's devastatingly simple, yet that nuance is his brilliance, and it's what makes Vacation so special. Optimism might be a strong word, but Rosenstock reaches something like acceptance on the record. So many artists fear that complacency or happiness might run their writing dry or that the extremes of emotion are the only options for a song that feels true and real. But Rosenstock dares to sing about feeling OK -- about coping with anxiety instead of succumbing to it, about wanting to be alive even though it's often boring and bland. "Everybody Loves You" nails the adult experience of anxiety: "Everybody that loves you will be leaving some day soon/ They've got problems to undo/ They've got paperwork to do." It might be more complicated than "My loneliness is killing me," but it's a lot healthier, too.

The album also marks a departure for Rosenstock in terms of genre and sound. It’s notably the first Bomb The Music Industry! record absent of any ska elements. But Rosenstock's continued dedication to the genre -- his work with Mike Park in the Bruce Lee Band, his reworking of last year’s NO DREAM as SKA DREAM (which attracted the attention of a surprising ska fan, Phoebe Bridgers) -- has only grown stronger in the years since Vacation's release. Rosenstock never distanced himself from his ska past; but on Vacation, he took stock of his contemporaries -- the folk punk of AJJ, the ebullient emo of Good Luck, the power pop of the Sidekicks -- and adjusted accordingly. He invited members from all three bands to contribute, remotely, to the record. And rather than feeling thin or commercial in the absence of horns and upbeats, the record sounds monumental: The opening riff on "Sick, Later," the crashing cymbals on "Campaign For A Better Weekend," and the glistening pedal steel on "Can't Complain" hint at the anthemic possibilities he’d realize more fully in his solo career.

Rosenstock didn’t explicitly state that Vacation was Bomb The Music Industry!'s last record, but the writing was on the wall. It was frankly surprising a band with their business model could remain viable as Rosenstock and his bandmates neared their 30th birthdays. The band never tried to project a glamorous fiction of rock 'n' roll, and their official hiatus announcement in 2012 was no different: "The 9-10 months of our lives when we are not playing music are not fantastic," Rosenstock wrote in a blog post. It was fortuitous timing, too: Bomb The Music Industry! released Vacation the same month Spotify came to the United States. Before long, the industry landscape that they had spent their entire discography subverting would soon adopt their free music model, albeit through the algorithmic lens of subscriptions and streaming.

And so Bomb The Music Industry! exists as a perfect time capsule: The proper nouns on Vacation don't exist anymore; the venues where Rosenstock played his iPod shows have largely closed. They were the last interview on the Tumblr blog One Week One Band, a website I will forever associate with my budding teenage obsession with music criticism. It's a bit disheartening to click through Bomb The Music Industry! interviews from just 10 years ago and discover that so many of the links are broken, but it's a perfectly digital obsolescence for a band often called "the Fugazi of the digital age." But really, Rosenstock put it best on Vacation: "Nothing's forever dude."