- Lakeshore Records

- 2011

The first time I saw Drive, it didn't even have the right music in it.

In the fall of 2011, I was studying abroad in Shanghai. I lived on a local campus, near an entrance called the Back Gate. It was lined with shops and restaurants, but when the sun went down it turned into a whole other thing. A vibrant night market, with street vendors cooking up skewers, people throwing down rugs piled with fake designer bags, home-modified scooters still ripping through the smoke and chaos. This would go on until, every couple of months, the cops came around and cleared it out, and then it would slowly creep back until it was bursting at the seams again.

But there was one stand that persisted, as if they had a bit more sway with the police. It was a little old couple, always standing stoically on the corner with house music blaring behind them no matter the hour. In front of them were card tables piled with crates of bootleg DVDs, all crammed in together in little plastic slip covers. We'd go by and file through like we were record shopping, and you'd come away with the popular shows of the time -- all the seasons of Weeds or Breaking Bad or whatever for something like three American dollars. They also had movies that were new back home but that weren't, or maybe would never, be in theaters in China. That's how I saw Drive.

Before I left for China, I could not wait for that movie. The neon noir, the stylization meets gritty violence, the presence of Ryan Gosling -- I was the exact kind of college kid mark for this stuff, and it was driving me nuts that I couldn't see it in Shanghai. All the way on the other side of the world, this dark American fever dream concocted by a Danish director seemed all the more enticing. But then I found it, with a hilarious bootleg cover that featured Gosling's face super-imposed on a military body, with his weird half-smile, while holding an assault rifle, in front of an exploding Eiffel Tower and a limousine with mobsters piling out and all manner of action movie tropes that, it would turn out, did not happen in Drive.

When I got home and watched it on my computer, much of the movie was we all know it now. The pop songs were all in there. But there was this nagging familiarity to the score I couldn't place until, about halfway through, I noticed the main theme from the preceding year's score from The Social Network. I've always figured it must've been a bootleg of some industry screener with placeholder score; the Social Network music synced up pretty well, anyway. But the point is: I first saw Drive when it was new, 10 years ago, and didn’t even get the whole picture of what the movie was or would become. Because in the ensuing decade, we have talked about the Drive soundtrack a lot.

Released in theaters 10 years ago today, Nicolas Winding Refn's Drive was adapted from James Sallis' 2005 novel. In Refn’s hands, Drive became an action movie that played out in its own world -- a meditation on action films overall, the Driver becoming a dark and violent sort of superhero. It was also a movie that took place in Los Angeles and, to some extent, reveled in that, but nevertheless felt as if it was in a frightening dream dimension adjacent to ours. The Driver is a mysterious character left unexplained, a cipher proceeding lonely through the world until circumstances lead him to the carnage of the movie's second half. Refn considered all of this a fairytale, infusing the film with a purity and romanticism early on while everything sinister threatened to overflow.

Accordingly, he had notions of what the music had to be to help create that otherworldly atmosphere. Rock music wouldn't do. "[The Driver] is half man, half machine," Refn told SPIN in 2011. "But the machinery, his car, is an antique. Late '70s bands like Kraftwerk inspired my idea of making a movie where the score was electronic, but at an infant stage -- crude in its technology, yet extremely poetic." Initially, he found his man in Chromatics/Italians Do It Better mastermind Johnny Jewel.

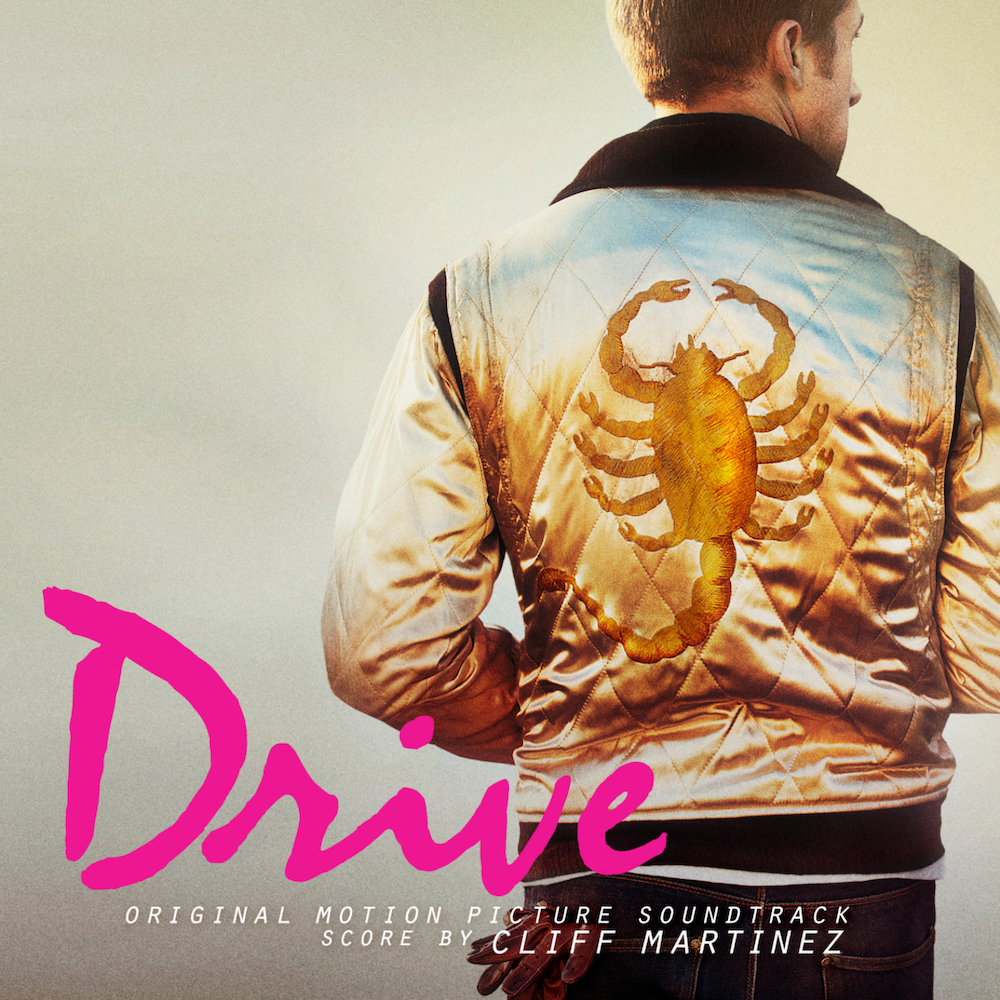

The pairing seemed as if it would be inspired. Jewel's whole aesthetic dovetails perfectly with the the film we now know -- a mixture of neo-noir, seedy LA nights, and yearning synthesizer music. Even the way Jewel's work references old films aligned with Drive. Some of his music did wind up in the finished movie, with Chromatics and Desire songs playing crucial roles. But in the end his score wasn't used; the studio replaced him with Cliff Martinez, the one-time Red Hot Chili Peppers drummer turned prolific score composer. Jewel reworked his unused score into Themes For An Imaginary Film, and it's a glimpse at how different Drive could've felt. Extending out from his usual songwriting, his would-be Drive score leaned hard into gloopy synthwave sounds and shimmering neon pinks and blues. That is still partially how we remember the music in Drive, but it's not what Martinez's score sounds like.

Upon revisiting Drive all these years later, I was struck by how different Martinez’ score is relative to how I recalled it. More often than not, it is sparse and ghostly; Refn had apparently been a fan of Martinez's restrained work on Sex, Lies, And Videotape, and Martinez himself once said he was taken aback by the ascendence of the Drive soundtrack because he considered it an extension of the "minimal, ambient" work he was already doing. That is what he provides in Drive, chilly backdrops that mirror the creeping dread of the film.

The score's pulse begins to build just a bit as the Driver and Standard approach their ill-fated pawn shop robbery. But mostly it hangs back, helping ratchet the tension of the movie until it all finally boils over. Even in its climactic moments, there's actually a shocking lack of music at key confrontations, like the silent horror of the Driver stalking down the beach to kill Nino. Then, in the final parking lot showdown with Bernie, the synths are almost more like funereal church music. "We wanted to put a horror tone into a film that isn't horror," Martinez said in that same SPIN interview. And, really, that's what his Drive score does. It’s less lush John Hughes pastels, and more foreboding John Carpenter iciness.

In a way, it almost doesn't matter that I first saw Drive with the wrong score. No disrespect to Cliff Martinez's work, which is perfect for the movie, but it's those pop songs early in the movie that people are talking about when they imagine the Drive vibe. Here, Jewel's contributions were indeed pivotal. Drive rumbles open with the foreboding subterranean throb of Chromatics' "Tick Of The Clock" for the initial heist scene. It's an impeccable sequence I can still vividly picture anytime I think about it. That hiccuping lean muscularity of the synth, Gosling's gloved hand tightening on the wheel before the getaway. For a taut, deliberate film, you are immediately brought into its strange world.

Then there's the Driver, the movie's vivid pink logo, and a shot of LA glittering in the night, all set to the opening theme of Kavinsky and Lovefoxxx's "Nightcall." Co-written by Daft Punk's Guy-Manuel de Homem-Christo, it's a brooding-then-pretty piece of Europop, fully introducing the weird tonal balance Drive strikes. Early on in the movie there are other crucial moments set to pop songs. The romantic driving scene with Irene and Benicio is set to College and Electric Youth's "A Real Hero," which became the spiritual theme of the movie -- a real hero and a real human being, the supposed divide of the Driver. Then, finally, there was Desire's "Under Your Spell," reverberating through the walls during Standard's welcome home party, with both Irene and the Driver missing the other.

A title like "Under Your Spell" goes a ways towards summarizing the effectiveness of these songs' appearances earlier on in the movie. This is where Drive spins its fairytale, how it enchants you. In "Tick Of The Clock" and Kavinsky's robotic drawl verses in “Nightcall,” you get the eerie undercurrents. But in the chorus of "Nightcall," and in "A Real Hero" and "Under Your Spell," you get the film's romanticism. In interviews from the time, Refn loved to talk about the importance of music -- how he and Gosling concocted elements of the film by driving around LA sharing songs, how the Driver could be a character so deeply alone that he occupies his nights driving listlessly with whatever soundtrack. While Drive may be patiently paced, it is also a movie with a heightened, not-quite-human emotional timbre. There is something fantastical in the use of these songs. And if Drive's world was recognizable but not quite our own, so too were these songs signifiers of distant, received memories while simultaneously playing as mutated echoes.

This is where Drive cast its long shadow of influence. It seems that '80s nostalgia has been ubiquitous, or at least reappearing in constant cycles, for something like 20 years now. But in the last 10 years, there was definitely a particular, prominent strain that Drive played into. Synthwave was already a genre by the time it got its big moment on the Drive soundtrack, but it gained wider notoriety from here, helping pave the way for other '80s homages like Stranger Things. But synthwave isn't really a direct retro pastiche, it’s more of a textural recollection from people who were either young children in that decade or weren't even alive yet. As with a lot of nostalgia, it's refracted. Over the years, the Drive soundtrack has become a constant reference point, a sort of shorthand descriptor for a reflection of a reflection.

That shorthand means that Drive didn’t just bring synthwave to a bigger audience, but also seeped into indie music again and again. Chromatics, and Johnny Jewel in general, are very much artists who trafficked in altered, filtered takes on the past; they too rose to greater prominence in the years after Drive. This particular kind of bleary, late-night '80s-nodding music appears again and again. In just the last few years, you had the Weeknd scoring one of the biggest hits in pop music history by tapping into this ethos, and you had Annie's long-awaited return Dark Hearts similarly exploring that sound -- '80s, but not literally something that could’ve existed in the '80s. When Natasha Khan released her last Bat For Lashes album, 2019's Lost Girls, she explicitly referenced watching Drive and feeling an '80s resurgence bubbling up at the beginning of the decade.

Looking back, it all seems sort of implausible: a meta action film, featuring the guy from The Notebook stomping a man's face in on his way to a new era of peak internet/indie acclaim, and a handful of obscure synthwave artists. When you consider the role of the internet in synthwave as a genre, or in how we collapse eras and constantly sift through nostalgia, Drive is almost less out of time and instead very of the 2010s. This could have been a strange cult film embraced by film nerds. Instead, it became a broad and pervasive cultural touchstone -- for a decade where, yes, many of us millennials were deep under the spell the unremembered '80s. But also for a decade where we forged ever deeper into a digital life, where time and place could be vividly represented or blurred altogether, where fact and fiction could melt together. You could still see Drive as a fairytale today; you could still imagine its soundtrack as gooey romanticism. But the world conjured up by the film and its music doesn't necessarily feel like a distant dream anymore. Drive is just another 21st century work arising from and tapping into how we can move through worlds tangible and online today -- eliding eras, borders, and realities.